Scott Rothkopf on Planning Jeff Koons: A Retrospective

Oct 23, 2014

Scott Rothkopf first became aware of Jeff Koons's work in 1994, when he stumbled upon an exhibition catalogue for the artist's first survey exhibition at SFMOMA in a bookstore in Dallas, Texas. Two decades later, he organized the most comprehensive retrospective of Koons's work to date. In this Whitney Stories Q&A, Rothkopf responds to questions about the four-year planning process for Jeff Koons: A Retrospective, which began with pinning printouts to foam-core boards and ended with one of the most challenging installations in the Whitney's history.

In discussing the organizing principles for this exhibition, you've mentioned a desire to restore the contexts around certain bodies of Jeff Koons's work. What are some of the curatorial strategies you used to accomplish this in real space?

Well, you can never truly restore the original historical context because that might have involved, say, the feeling of walking into one of Jeff’s galleries in the East Village in the 1980s. Some curators do try to establish a sense of context through photographs, timelines, or archival material, but I didn't do that because I wanted the work to feel very alive in the present. I wanted to reconstitute each of Jeff's bodies of work in-depth. Today one often encounters works like Balloon Dog, or Rabbit, or Michael Jackson and Bubbles as these individual icons, and it was very important for me to consider how they emerged in very complex series that involved many different kinds of images, objects, materials, and scales—and when they were put back together, you would start to see new things about these bodies of work.

Jeff was closely involved in the planning process for the exhibition. Would you describe the process as collaborative?

Yes, it was a very close collaboration from the beginning. We were in touch every week for about four years, sometimes on a daily basis. We had models [of the exhibition] both in my office and in his studio, and we worked together on everything from the selection of the works to their placement in the galleries, to all the details of the catalogue. There were times that we didn’t agree at first, but we would always find different solutions to reconciling our different perspectives on Jeff's work.

Could you give an example of a conversation that gave rise to a new strategy?

There are examples of curatorial decisions that Jeff wouldn't have explored on his own. In the Banality room, we feature ten sculptures all facing forward in a line. At first Jeff was hesitant about this idea because it didn't mesh with his own history of understanding and displaying these sculptures, and so it took some time for us to arrive at a point where he really understood and felt comfortable the concept. Now he really likes it, but I realize it can sometimes be hard for an artist to be curated because they're seeing another point of view overlaid on top of their work. Part of Jeff having the retrospective at the Whitney meant he had to grapple with a different intelligence coming to terms with his work in a new way, but we had a great time and both learned a tremendous amount from one another.

What was your thinking behind arranging the Banality sculptures in a straight line?

The whole history of modern sculpture is in some ways a story about the viewer circumambulating or walking around the sculpture, whether it's a Matisse or a Richard Serra. But in this series, Jeff made sculptures that all had faces that look directly at you. The sculptures are so frontal.

So what would it mean to emphasize the imagistic quality of these objects, many of which were derived from collages that were based on photographs? In a way, a sculpture like Michael Jackson and Bubbles might exist in our mind already before we see it in person, because we've seen it on the Internet or on a postcard. I wanted to imagine a way that the sculptures could almost acknowledge their status as images in our minds, and this display device helped to do that by letting us see them as figures on a runway, or people in a lineup, or even curios on a display shelf. So an installation decision like that was intended to bring out all of those themes and qualities in the work.

It was also extremely practical. Those objects are very fragile and valuable, and I would have had to show fewer of them in a similar space if I’d separated them and surrounded them with individual risers or stanchions. Consolidating the protective barrier was a way of saving space. But that was really a secondary concern.

How did the planning process for this exhibition compare to others?

It was certainly the most complicated exhibition I've ever worked on—in fact the most challenging in the history of the Whitney, at least for a single artist exhibition. There were so many issues to deal with, whether that involved getting collectors to part with very valuable and fragile works, or raising funds to support an endeavor of this scale, or the very extreme art handling challenges—how to get these objects into the building and how to get them installed. Some [works] were nail-biters because they weren't finished until just moments before the exhibition opened. So at every turn, the show was complex and daunting.

It was exciting to be a part of a team that really handled the challenge so beautifully and went the distance for the artist. We talk a lot at the Whitney about being the “artists' Museum,” and I think it's sometimes hard to say what that means, but in making this show we really tried to do everything we could to make Jeff look his best, and to realize an exhibition in the most perfect form that we could, without cutting corners, without making compromises. I think the show reflects that level of commitment that we have to artists, just the way Jeff brings that commitment to his work.

A lot has been written about the challenges involved in installing this exhibition. What are the rewards of showing Jeff Koons's work in this space at this time?

We thought a lot about when it would make sense to do this show, and many people assumed it would be something to do in our new building. But we really felt that when we open the new building, we want to start with the collection and bring a sense of history downtown. At the same time we didn't want to leave the Breuer building feeling nostalgic, but wanted to have a real sense of occasion, of celebration, of doing something unprecedented, and Jeff was the perfect fit for all of those factors.

In addition, Jeff originally showed some of his work in spaces in SoHo and the East Village that were not particularly refined, and the kind of roughness of those spaces is in some ways recalled by the physicality of the Breuer building. There’s a sort of tension between [the building and] these perfectly finished objects.

And finally, it's a site that actually prompted key questions in Jeff’s career; he recalls seeing a Jim Nutt show at the Whitney in 1974, and he exhibited in the Biennials over the years and in exhibitions like Image World, as well as many different collection displays. So it was nice to have that sense of Jeff's history overlaid atop his work.

What planning materials did you use?

Any exhibition that I make usually starts with a super old-fashioned image board. It's almost embarrassing because you would think that we would do all of this on the computer, but in order to visualize the scale of 100 objects together, I still use foam-core board with little printouts tacked to it. That's a device that really helps me organize the series, and also understand which works I've selected from each series and what the relationships might be.

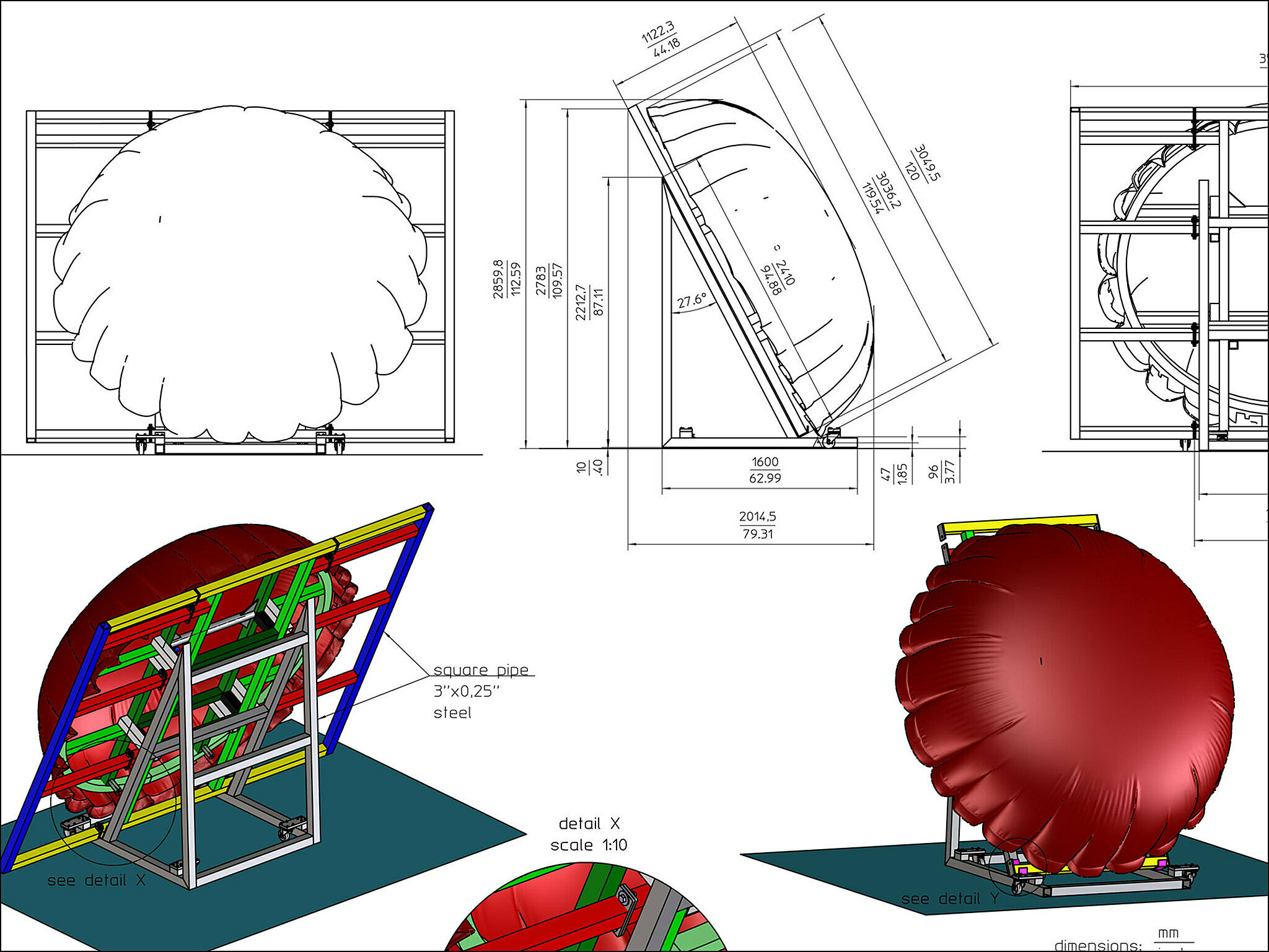

And then you get into the complicated problem of fitting all of these things in the actual space. Working with the exhibitions team, we make floor plans and layouts through CAD. When we're installing, in many cases we can't move around these very fragile works, especially the large ones, as much as we might move a painting back and forth. So we actually used cardboard maquettes in the gallery as a kind of device to test the placement of objects before the actual works arrived. We have those for many of the works in the show. As you might have seen on the New York Times website, working with the studio and the fabricators, we did small models and computer renderings of the clearances of some of the pieces in their crates. So it really runs the gamut in terms of preparation and the materials we use.

Were there any surprises that you experienced during the planning or installation process?

The show was full of surprises—sometimes more than I might have liked! But that's what kept it such an interesting process. Sometimes works would change hands while we were planning the exhibition; sometimes they proved to be slightly different dimensions than we thought they were, which affects the way we get them into the building; sometimes we worried that works we were excited about showing might not be finished.

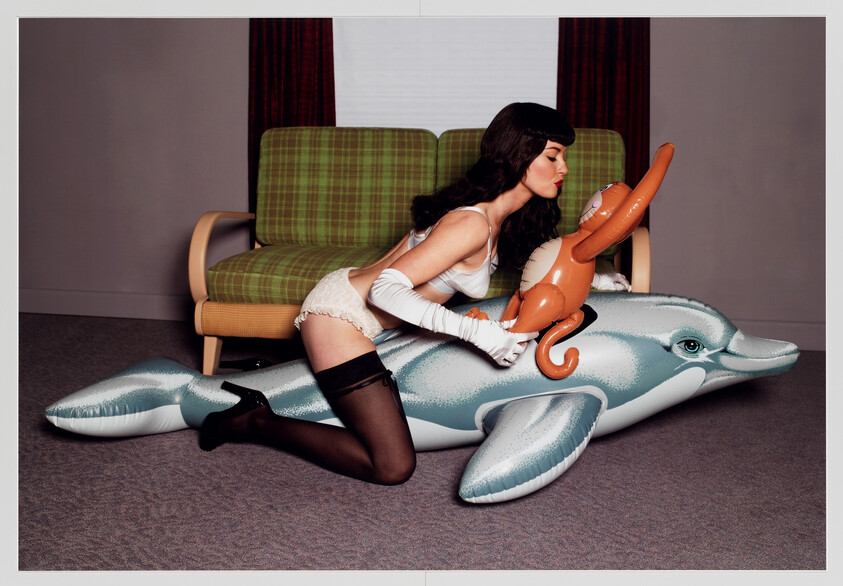

But there were a tremendous number of truly wonderful surprises, too: the connections that I made while looking at the bodies of work together and at things across time; the surprise of looking at some of the refabricated early Inflatables with the little porcelain figurines, and seeing how directly they relate to the Gazing Ball work that Jeff is making today; the incredible, wonderful delight on first seeing Play-Doh, a sculpture that took twenty years to finish and turned out to be one of Jeff's masterpieces. I think it's very rare and lucky to be able to present a survey of an artist's work going back thirty-five years and to feel that some of the newest pieces are just as strong as some of the early ones.

Upon seeing the work installed, have you had any new insights about Jeff's work? You mentioned the Gazing Ball sculptures and how they relate to very early Inflatables. Are there other examples to come to mind?

Even having studied Jeff's work for twelve years, I learned more in the last three months being around the work almost daily than I had in all the rest of the time combined. That has to do with connections that I'm making between different bodies work, and it has to do with learning how these things are actually made and what they're made out of. I have gained a lot from the expertise of my colleagues in the conservation department, whether it's the ways that the vacuum cleaner pieces are wired, or how to care for the porcelain objects’ surfaces, or what's really involved in balancing a basketball in a tank. Until you see them done, these things are very hard to understand in the abstract. It's been a great learning process for me.

I've also been surprised by the way the diversity of Jeff's work can coexist with a sense of coherence. It's amazing to me that sometimes in a given series he could make three works that look so dissimilar from one another that they might have been made by three different artists. Let's say, the bronze Aqualung with a Nike poster, and a basketball floating in a tank. There's nothing to suggest, apart from a shared theme or allegory, that these works are were made by the same person in the same year. And I think that if one looks at Jeff’s work across his thirty-five year career, his range of materials, scales, and images is as diverse as those of anyone working today, but at the same time those pieces fit together to make this whole that somehow makes sense and suggests a singular point of view. It’s been interesting to acknowledge this multifariousness in his work, as well as the sense of a seamless trajectory.

How do you expect the exhibition will change as it travels?

The exhibition is being reformatted for each venue. It will have a very different feeling in each place. At the Centre Pompidou in Paris, we're not building separate galleries for each body of work, so one will see works from multiple series at one time and have a more expansive view across history. At the Guggenheim in Bilbao, it's very exciting to work in Frank Gehry's iconic building. With the topiary Puppy installed permanently there, you have a great sense of connection to one of Jeff's best known works that was not part of the Whitney show. In each place the show will change, and I look forward to seeing it through new lenses.

What do you think your particular stamp or mark on this work might be?

Well, the craft of monographic exhibition making is seldom discussed these days. I think people are more aware of finding a curator's voice in a “big idea” show like a biennial, where they're looking for a theme pertaining to a group of artists. People often assume that making an artist’s retrospective is self-explanatory because you just take one artist's work and put it in order. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth in terms of how one actually constructs an argument or narrative, or a sense of pacing and scale. It's really like shaping a person's life story. Someone else could make another Jeff Koons show with different objects, or even with many of the same objects, but it would have a totally different feeling.

In a way, I wanted to approach it with both an intense precision and a lightness of touch. I didn’t mix different bodies of work but was hewing to Jeff's series as he conceived them and to their chronology. Yet in every gallery I tried to inflect the experience of the work with a different feeling or sensation. The way the objects are installed, the logic of the installation, changes from one space to the next. In the room with the vacuum cleaners, you're very aware of them all facing forward, and the strict geometry of these pieces is emphasized by the grid of the Breuer building’s ceiling. That experience is very hard and cold, even aggressive. The Banality sculptures involve yet another strategy of display that we already discussed. In Made in Heaven things feel a little bit more open and floating, maybe a little more poetic in their sensibility. In each body of work, I selected objects that I wanted to engage in a specific dialogue with one another and then I tried to bring that conversation out through the way the objects were physically situated in space. In the Antiquity gallery you enter into a situation almost like a classical sculpture gallery; you are flanked by two Venuses facing one another and straight ahead you confront this image of coupling between a man and a woman. In a way, if I do my job right, visitors are not that aware of these decisions—things just feel kind of right and inevitable. And yet everything from the light gray paint that we used in the Gazing Ball room to the lighting strategies in each gallery were highly specific decisions.

One of the risks going into a show like this is the error of “too-muchness.” When you're giving an artist of Jeff's fame an unprecedented amount of space, you don't want [visitors] to leave the exhibition feeling like it dropped off at the end, or like they've eaten too much cotton candy. You have to have a sense of pacing, and part of that is created through the selection of objects, and the other part is varying that sense of experience from room to room. It's a kind of editorial challenge, but also an architectural and sculptural one on the part of the curator. I hope people think that it made sense to present the work at this scale, in this space, and in this way, and that it's not an exercise in spectacle. It had to be that the work earned and owned its place, and I feel good about the way that played out.