Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art | Art & Artists

July 13–Sept 30, 2018

Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art | Art & Artists

Livia Corona Benjamin

2

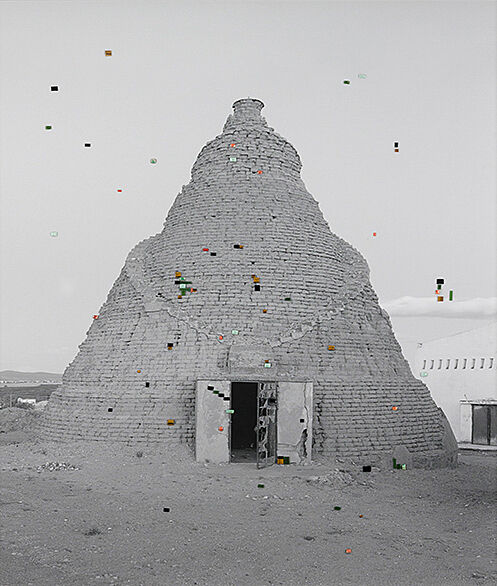

Livia Corona Benjamin’s works stem from her long-term, ongoing project exploring the conical grain silos in rural Mexico known as graneros del pueblo that were built under the now defunct government program CONASUPO (Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares). In 1962, CONASUPO commissioned Mexican architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez to design an architectural template that farmers could build themselves using the construction materials they had at hand. The conical shape of the silos is reminiscent of pre-Hispanic pyramids but the adaptation of the blueprint by local farmers make the more than 4,000 grain barns an example of vernacular architecture in Mexico. The CONASUPO grain project was a failed government program that left behind thousands of these structures in disuse.

Working entirely in analog film from a single black-and-white negative, Livia Corona Benjamín made her photograms titled Infinite Rewrite through multiple exposures in the darkroom. Each exposure fractured the image further, generating ranges of color not present in the original negative and resulting in pixel-like shapes that are analog yet give the appearance of having been digitally manipulated. The pixels reference stone and shell mosaics in pre-Hispanic art. The repetition of the abstract forms nods to the many versions of Mexican grain silos made from one master design during the CONASUPO initiative, and also comments on the role of photography in the era of digital automation.