Dawoud Bey: An American Project | Art & Artists

Apr 17–Oct 3, 2021

Dawoud Bey: An American Project | Art & Artists

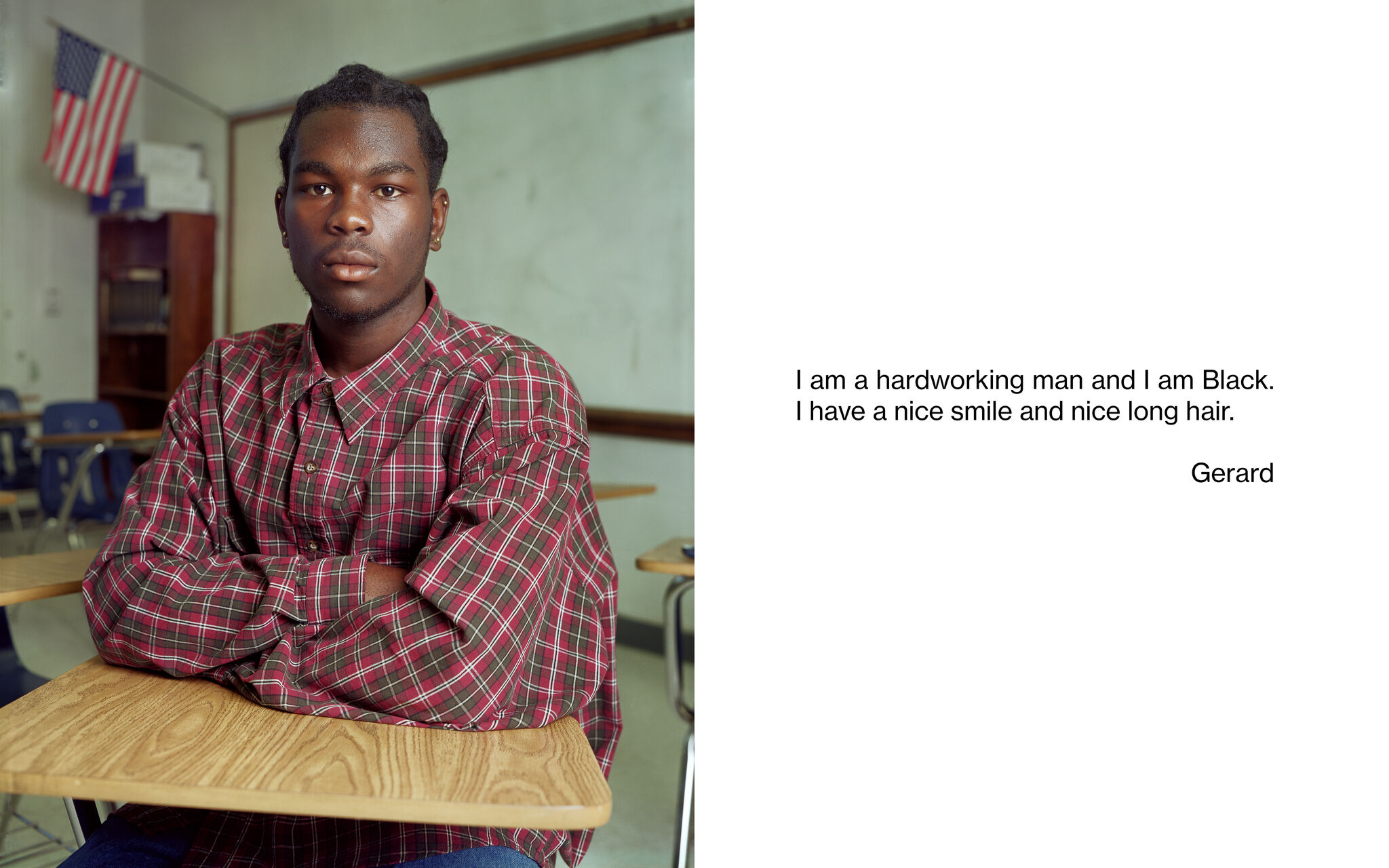

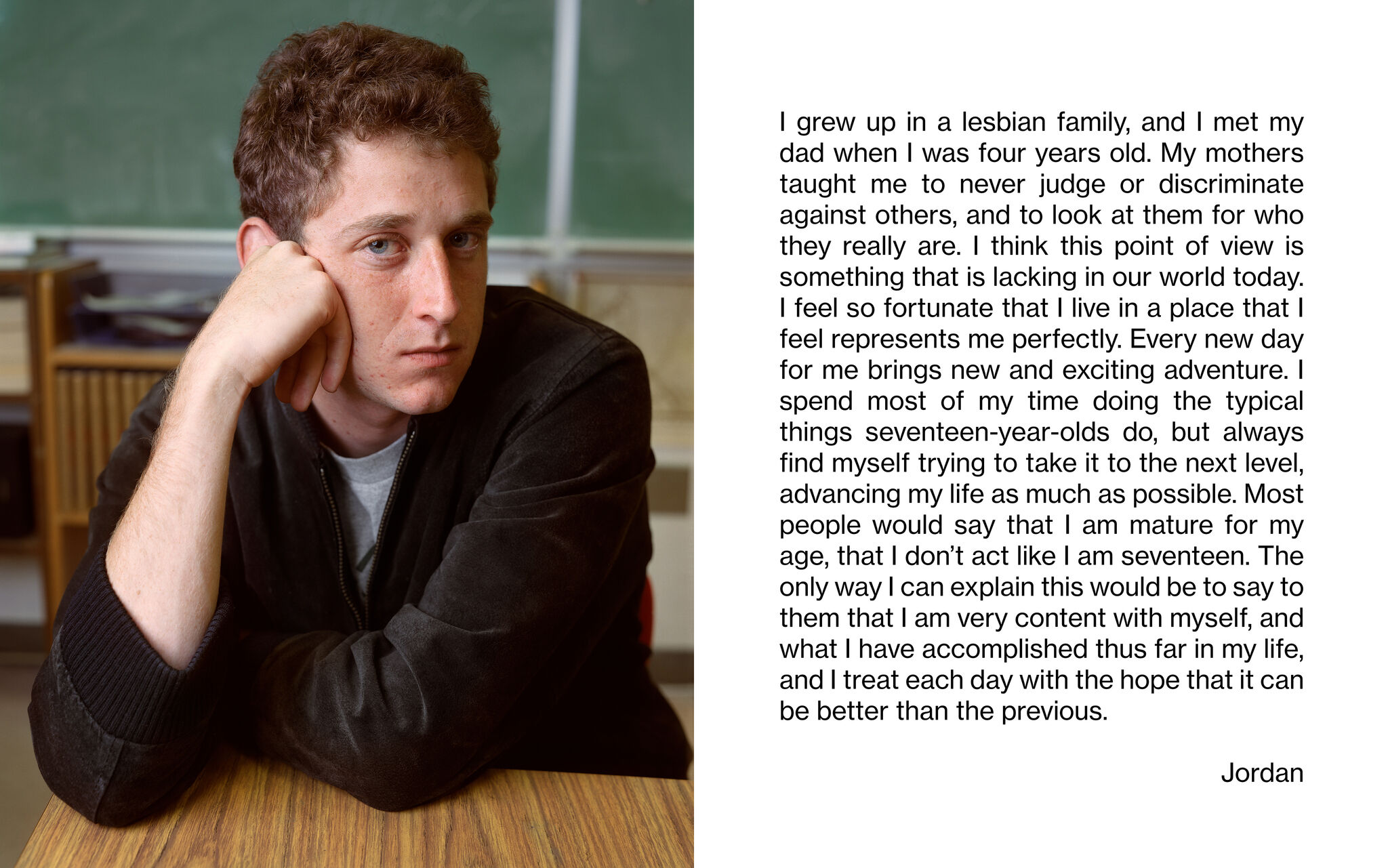

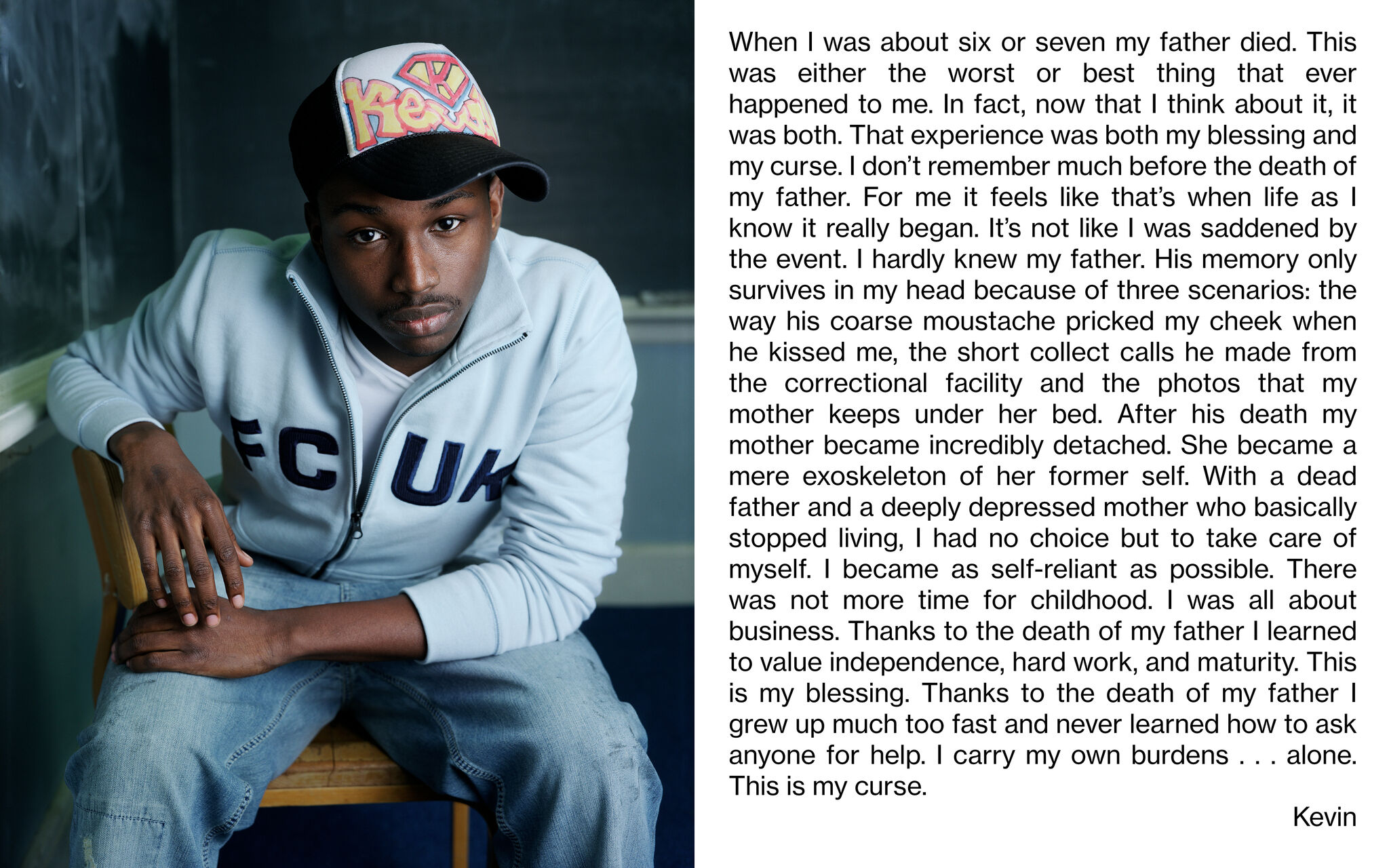

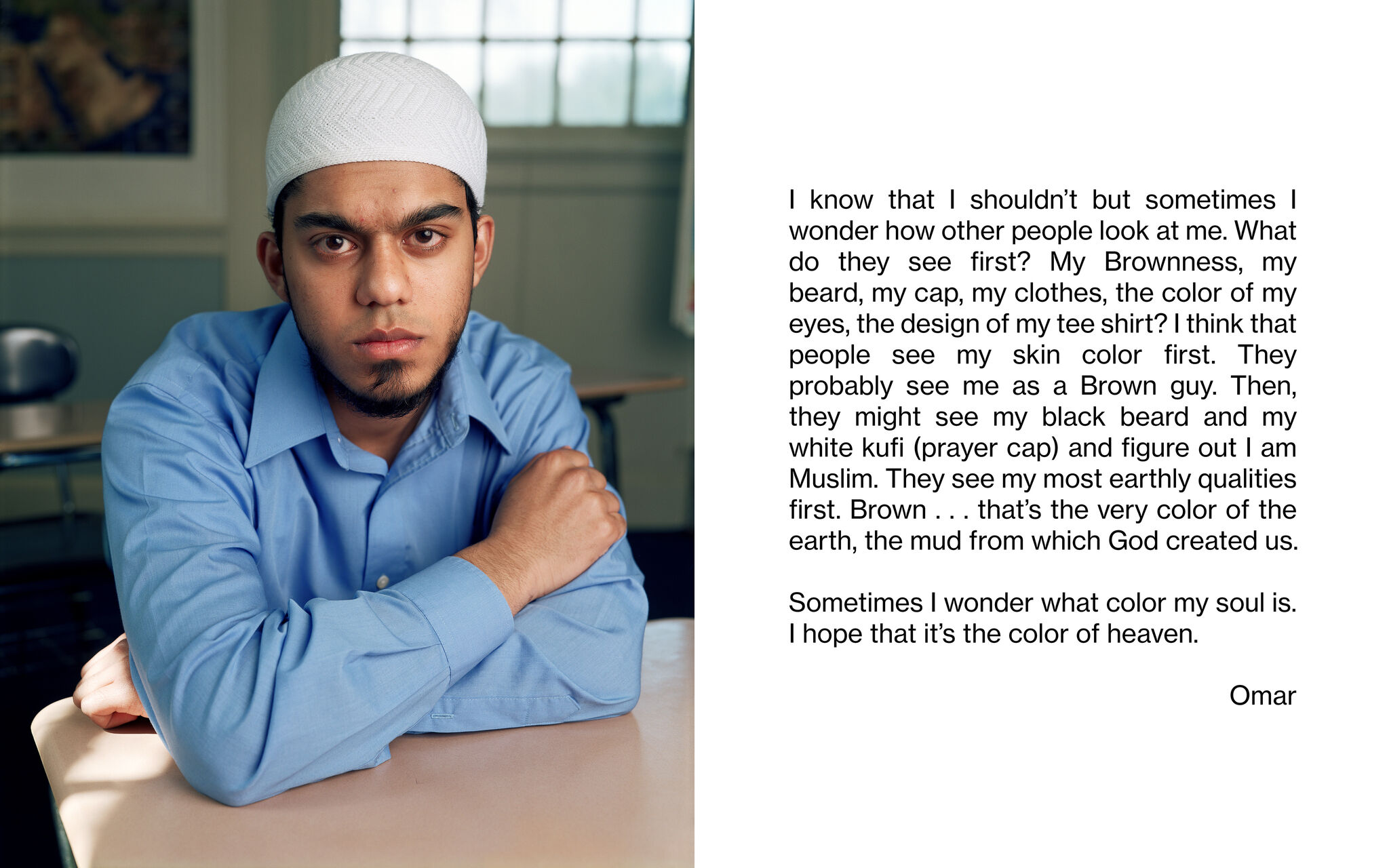

Class Pictures

5

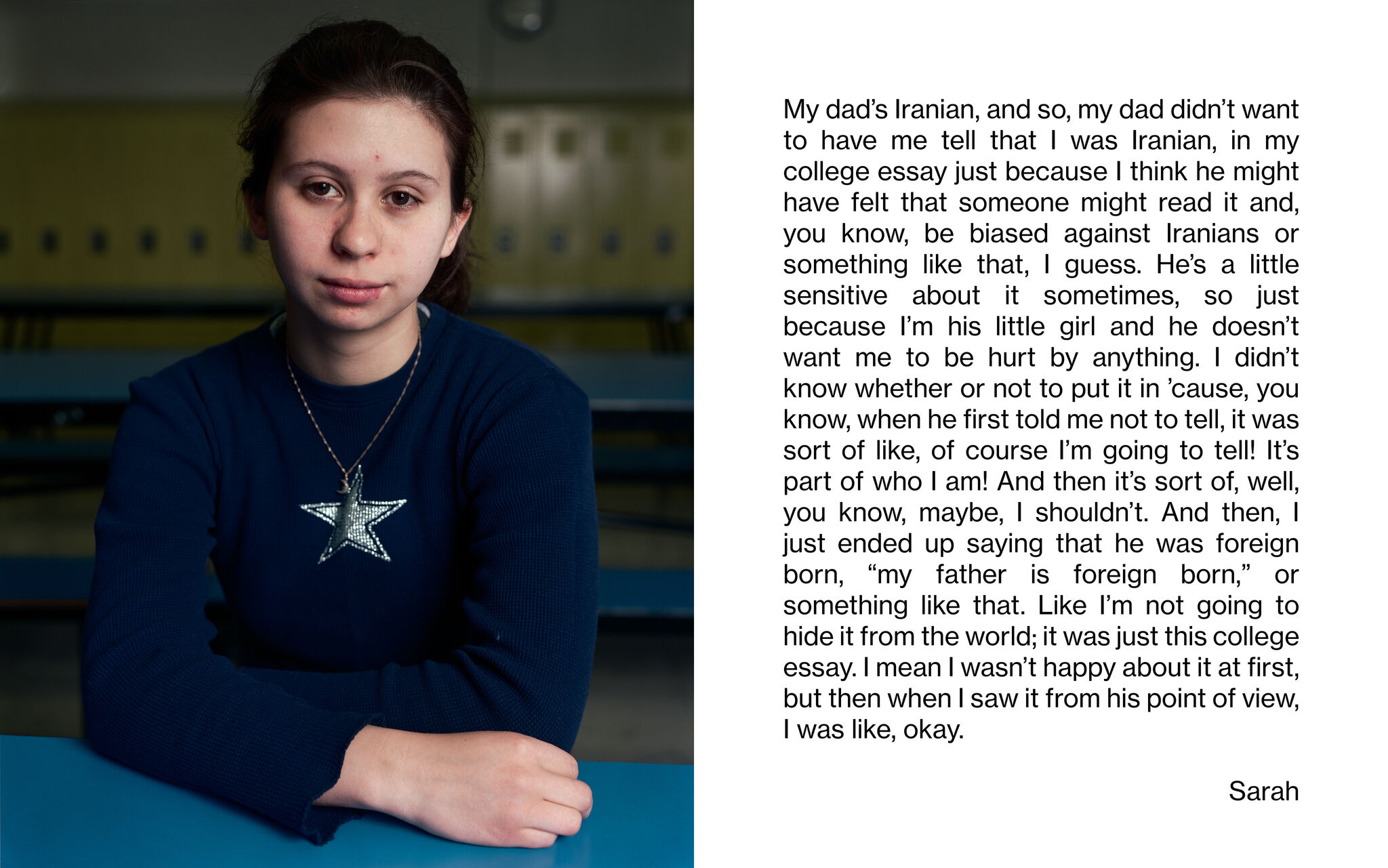

Bey has long understood that the act of representation—as well as the corollary act of being seen—is both powerful and political. In Class Pictures (1992–2006) he once again turned his attention to teenagers, a population he felt was underrepresented and misjudged, seen either as “socially problematic or as engines for a certain consumerism.” The series originated during a residency at the Smart Museum of Art in Chicago, where Bey began working with local high-school students; during residencies at other museums and schools around the country, he expanded the project to capture a geographically and socioeconomically diverse slice of American adolescence.

Working in empty classrooms between class periods, Bey made careful and tender formal color portraits of teens. He then invited them to write brief autobiographical statements to accompany their images, giving his subjects voice as well as visibility. Many of the residencies also included a curatorial project with the students using works in the museums’ collections. While the photographs and texts are what remain of these projects, it is the collaborative undertaking that Bey considers the work of Class Pictures.