David Hammons: Day’s End | Art & Artists

David Hammons: Day’s End | Art & Artists

Bringing Day’s End To Life

2

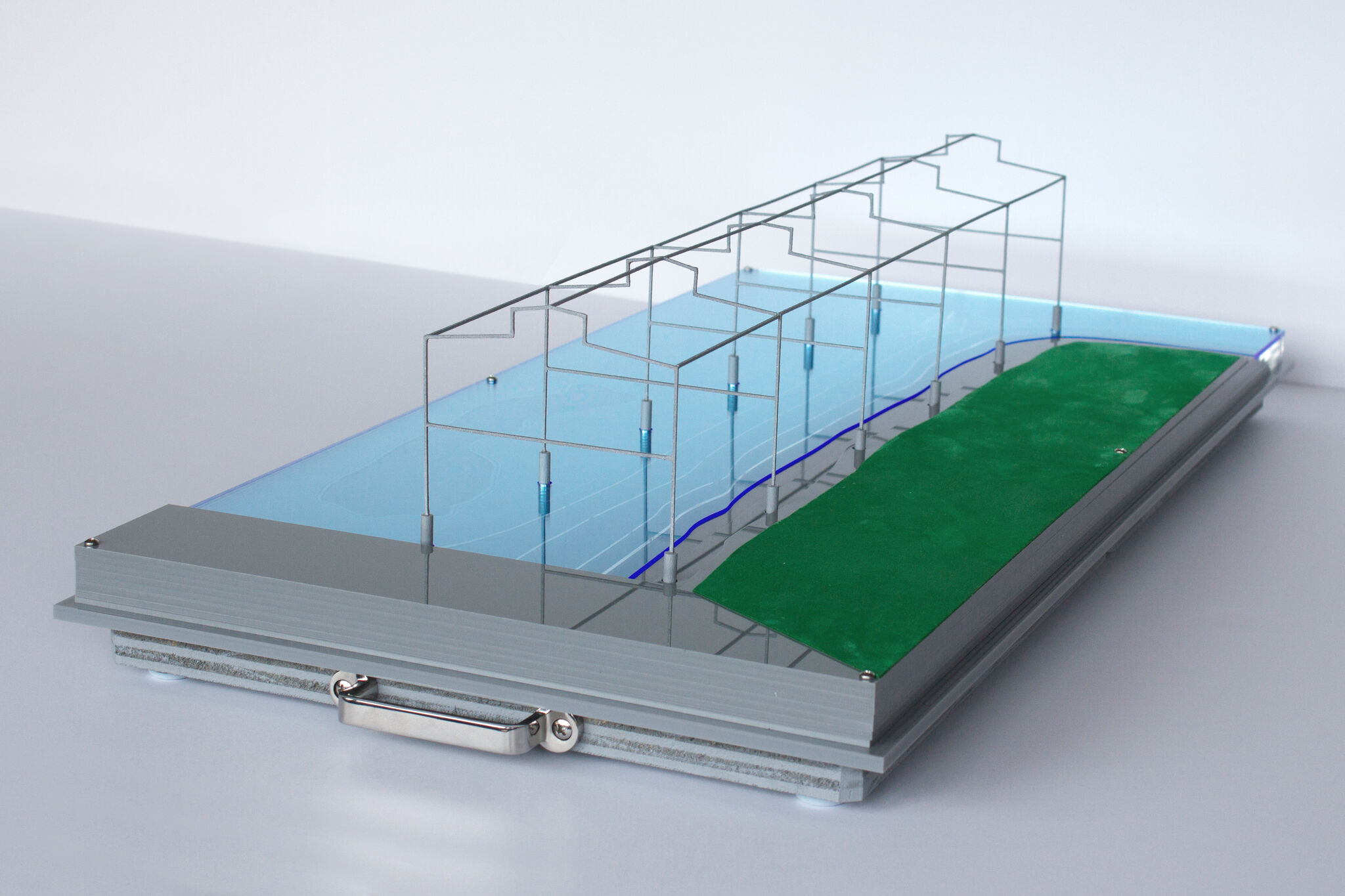

As a sketch, David Hammons’s Day’s End (2014–21) appeared to be a delicate system of lines. But to build such a thing in three-dimensional space was a feat of engineering. Guy Nordenson and Associates (GNA) was tasked with transforming Hammons’s drawing into a large-scale steel structure that could endure the elements through time and still honor the ethereality of the artist’s vision.

The question of how best to realize Day’s End posed a series of logistical challenges. Hammons envisioned a slender frame comprising as few parts as possible, so the engineers at GNA designed complex pipes that could reliably bear the weight of this colossal 65 × 325 × 52-foot sculpture. Their thinness then made them susceptible to vibrations from the wind and required a special welding technique to fortify the structure’s integrity. It was also imperative to Hammons that his artwork occupy the precise coordinates of Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975) so as to evoke its ghostly memory. But documentation of Pier 52 was scant, which meant tracking down and scrutinizing what archival materials could be found. With the help of old photographs and Geographic Information System Mapping technology, the team successfully determined the location and dimensions of the pier; in fact, their analysis was so exact that they uncovered its remains during construction. Like Pier 52, Day’s End is anchored in the bedrock of Gansevoort Peninsula and stretches into the Hudson River. The variation in soil quality on land versus under water presented another challenge for GNA. The solution was to reinforce the submerged end of the structure by drilling into the earth below the Hudson River at several times the height of the artwork itself.

Over the course of seven years, the process of bringing Day’s End to life unearthed layer upon layer of local history. Long before the Gansevoort Peninsula was known as such, the region served as an oyster midden for Lenape inhabitants. It later became the site of Fort Gansevoort, created by the United States Army in preparation for the War of 1812 between America and Britain. Both the fort and the peninsula were named after the Revolutionary War Colonel Peter Gansevoort (1749–1812), who was also the maternal grandfather of celebrated American novelist Herman Melville (1819–92). After Melville published Moby Dick in 1851, he spent nearly two decades working as a customs inspector on the Gansevoort Street Wharf. The peninsula is the final remnant of what used to be Thirteenth Avenue, a landfill created by the city in 1837 and destroyed around the turn of the century to make more space for steamships. And it was the epicenter of a thriving queer community that enriched the waterfront in Matta-Clark’s day.

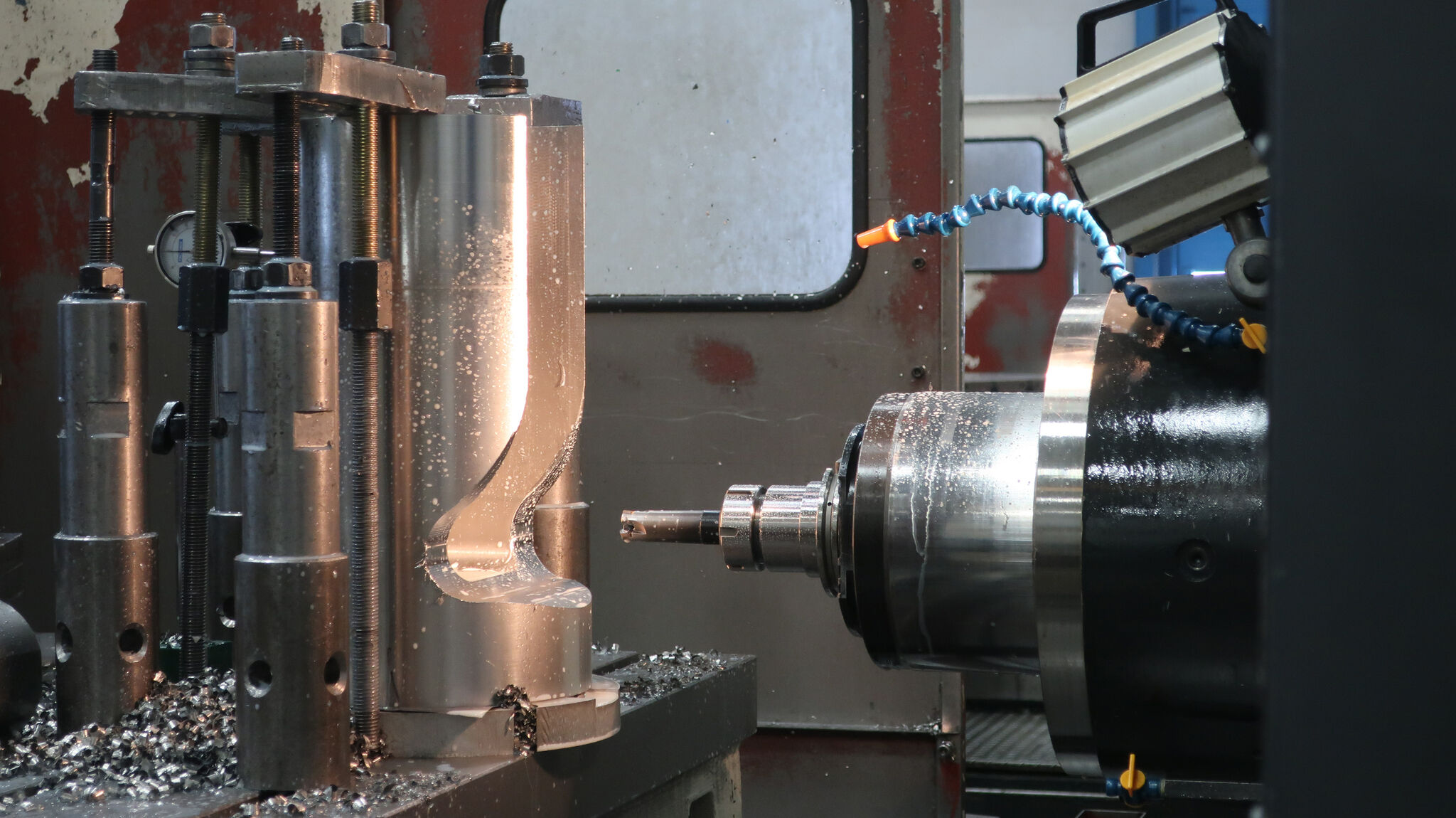

Hammons’s Day’s End has been built to last, thanks to thoughtful engineering and custom fabrication across five countries. In the United States, Fort Miller Company developed a special casting process for the concrete columns. In Canada, Mariani Metal Fabricators assembled the cast, welded, and machined connections in accordance with engineering requirements. The stainless steel castings were designed by Cast Connex in Canada and manufactured by Altona in Brazil, and the pipes—using steel sourced from France—were made by Rivit and Piemme in Italy. The castings, pipes, and couplers were then assembled into beams and columns by Mariani Metal Fabricators back in Canada. In its permanence, Day’s End alludes to the many narratives that came before it.