Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay:

Indigenous Space,

Modern Architecture,

New Art

Conceptual Blueprints: Artistic Approaches to Indigenous Architecture

The great shelter, the shabono, also reflects the Indians’ conception of the universe. The central plaza is the celestial vault, and the low part of the roof is a replica of the low part of the sky—conceived as a convex structure—where it meets the disk of the earth.

—Jacques Lizot, Tales of the Yanomami: Daily Life in the Venezuelan Forest

Two years before I was born, the Whitney Museum of American Art had already organized an exhibition exploring ideas central to those in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art. Allow me to explain. In 1978, at coincidentally the same age as I am now, a thirty-eight-year old Chilean artist by the name of Juan Downey presented his video works The Abandoned Shabono and The Singing Mute at the Museum.This was actually not the first time the Whitney had exhibited the work of this artist. In 1976 the Museum had shown his ambitious multichannel and performatic Video Trans Americas in Juan Downey: Video Trans Americas, curated by John Hanhardt. Curator of film and video at the Whitney Museum from 1974 to 1996, Hanhardt first met Downey (1940–1993) in the early 1970s. In 1976 Hanhardt curated the second presentation of Video Trans Americas (it was first presented in 1974 at Syracuse University’s Everson Museum of Art). Hanhardt then went on to include Downey in the single-artist exhibition in 1978 as part of the Whitney’s New American Filmmaker series and group shows in 1980 and 1984. Downey’s work has also been included in several Whitney Biennials: 1975, 1983, 1985, 1987, and 1991.With this single-artist exhibition, the Whitney demonstrated a strong commitment to Downey’s remarkable ideas, especially his interest in imbricating the built environment of Indigenous people from the Americas with Western audiences and institutions in New York.For more information about the impact of Downey’s ideas on the art world, see Grace Glueck, “Art People,” New York Times, September 24, 1976; and Valerie Smith, ed., Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect (Cambridge, MA: MIT List Visual Arts Center, 2011).

The Abandoned Shabono (1978) in particular resonates with the concepts at the core of my exhibition Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay. The video encapsulates an idea that informed Downey's practice for at least a decade: the architecture of Indigenous groups acts as a regulating force of social and cosmological organization. The shabono (a lean-to, communal hut) was such a structure for the Yanomami Indians of the Amazon, with whom Downey lived for eight months. Importantly, the shabono was biodegradable, which distinguished it from what he called the “architecture of permanence” of other Indigenous groups. In a proposal for an unrealized documentary, Downey wrote: “Unlike the Inca, whose buildings lay permanent claim to the land that they occupy, the Yanomami structures are designed to allow nature to reclaim them after a relatively short period of time. The shabono is the communal skin that holds the group together, but it is a skin that is periodically shed and built anew.”Juan Downey, “The Blueprints of Power: A Documentary of Permanence and Transition in the Architecture of the Indians of the American Continents, A Proposal for a 58-minute Color Documentary for Public Television by Juan Downey, August 1987.”The broad spectrum of Indigenous building techniques and their implications for society that Downey captured and translated into video art are of enduring relevance to the seven LatinxLatinx is a gender-neutral term for people of Latin American heritage.artists in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: william cordova, Livia Corona Benjamin, Jorge González, Guadalupe Maravilla, Claudia Peña Salinas, Ronny Quevedo, and Clarissa Tossin.

The very structure of Downey’s video—its architecture, if you will—discloses a tension between the environment that the Yanomamis built for themselves based on knowledge passed down through the centuries and the one built around them by the modern world. Footage of the Yanomami is interspersed with that of Downey and French ethnologist Jacques Lizot sitting in a nondescript television studio discussing their personal observations of the Indigenous people, whose sole form of expression in the work is through the actions caught by Downey’s video camera during his limited time there. The final shots of The Abandoned Shabono show men clothed in Western garb engaging in heavy drinking and fistfights; the viewer is left to assume the men were once part of the Yanomami community or other Indigenous groups. In one fell swoop, the narrator blames industrialization for threatening their existence while at the same time ignoring the fact that modernity—including technologies such as video—could be implicitly transforming these societies.

Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay similarly seeks to make evident the significant and sometimes problematic points of contact between Indigenous concepts of space and the canon of modernity. Expanding on the precedent established by Downey and other conceptual artists such as Leandro Katz, the artists in the exhibition are cognizant of the burden that modern history has placed on the legacy of Indigenous building practices and do not intend to fetishize it or to ignore it. Recent exhibitions, most of which have been organized by New York museums, have paid particular attention to the modernist project in Latin America and its influence on architecture, art, and design.Here I am referring to the Museum of Arts and Design’s New Territories: Laboratories for Design, Craft and Art in Latin America (2016), the Museum of Modern Art’s Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955–1980 (2015), the Americas Society’s Moderno: Design for Living in Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela, 1940–1978 (2015), and the Bronx Museum of the Arts’ Beyond the Supersquare: Art and Architecture in Latin America after Modernism (2014).With words such as “development” and “progress” featured prominently throughout the catalogue essays and curatorial statements, curators and art historians have staked a claim for the rise of modernism as the ultimate paradigm for the history of the Americas. Such opportunities for privileging the role that the modernist project—in all its idealism as well as failures—has had in the arts have existed for almost a century and will most certainly continue being the focus of many curators and scholars.

The lens through which we assess the past needs adjusting, however, and the methodology that allows for this restructuring in epistemologies can be found in decolonial thinking. Decolonial interventions in museums with collections of precolonial and colonial art are increasingly common ways of questioning the manner in which institutions have displayed works from non-Western cultures. Writing on the exhibitions Black Mirror (Espejo Negro) at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in 2008–9 and De/Construcción de una Nación at the Museo Nacional de Arte in Mexico City in 2012–13, Jennifer Reynolds-Kaye has argued that museums are “rife for decolonial interventions given that they have been imbricated within both historical colonialism as storehouses for expropriated objects and coloniality, and barometers of beauty and good taste.”Jennifer Reynolds-Kaye, “Exhibiting the Decolonial Option: Museum Interventions by Pedro Lasch and Demián Flores,” E-misférica 11, no. 1 (2014).But how does one make a decolonial installation in a museum of modern and contemporary art? How can an exhibition be designed decolonially?

First, we work from the understanding that to talk about indigeneity in the Americas is to speak in the present tense, just as the seven artists selected for Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay do.I owe much of the inspiration for this exhibition to the seven artists in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay, as well as to many others based in and out of the United States, such as Gala Porras-Kim, Rafa Esparza, Beatriz Cortez, Tatiana Parcero, Benvenuto Chavajay, Noé Martínez, Sergio Valencia Salazar, and Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, just to name a few.In fact, language is a major factor in the conception of this exhibition. Faced with the realization that neither English nor Spanish could truly hold the vastness of what architecture and other related concepts mean to Indigenous communities, I chose a title with three words in Quechua, the pre-Columbian language most spoken today in the Americas, to best reflect the richness of a philosophy that sees the cosmos and the earth as interconnected. Pacha denotes universe, time, space, nature, or world; llaqta signifies place, country, community, or town; and wasichay means to build or to construct a house. It must also be said that these artists subscribe to the idea that modern and contemporary art has an even more ancestral lineage than European art. Furthermore, in the case of those artists who live in the United States, their work can complicate the simplistic ways in which the Latinx community is represented—and often vilified—in this country by pointing to the hundreds of Indigenous groups still present here and throughout Latin America. Through its thesis, its selection of artworks, and its very exhibition layout, Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay aims to make explicit this grappling with the ways in which history has been told and retold.

The exhibition is unambiguously anchored in a feminist perspective. Opening with the monumental projection of Clarissa Tossin’s Ch’u Mayaa (2017), featuring dancer and choreographer Crystal Sepúlveda, Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay asks us to consider what semiotician Walter Mignolo calls the “decolonial option.”Walter Mignolo described the “decolonial option” in the following way: “The decolonial option is not aiming to be the one. It is just an option that, beyond asserting itself as such, makes clear that all the rest are also options, and, not simply the irrevocable truth of history that has to be imposed by force and fire.” Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham, NC, and London, United Kingdom: Duke University Press, 2011), 21.The dancer’s movements inside, outside, and across Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House (built between 1919 and 1921) in Los Angeles result from Tossin’s research into the gestures and poses found on Maya ceramics and in murals, which often present bodies in hieroglyphic form. Tossin (b. 1973) posits that the iconic building can be activated in the very same way Maya people, specifically women, would have used one of their temples. Rather than upholding Wright’s “option” of borrowing from many diverse decorative languages to espouse a Mayan Revival style in his designs, Tossin presents viewers with an alternative. The building, in which every design element both inside and out was imagined by a master of Western architecture, is activated through the performance of a Brown, Latina woman whose mighty presence is anything but ornamental. Tossin resignifies Wright’s building by closing the gap between an ancient Mesoamerican temple and a modern Los Angeles mansion.

Gendered spaces are also explored in the exhibition with an installation of sculptures by Claudia Peña Salinas (b. 1975). Her work imagines the ideal residence for Tlaloc, the Aztec deity of rain, and the water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue—the paradise known to the Aztecs as Tlalocan. Playing with the ambiguity and controversy around the sex of Tlaloc and whether this assumed male deity was actually Chalchiuhtlicue, Peña Salinas constructs a space where gender is fluid, signaled by the combination of names in sculptures such as Tlalicue (2017). This imagined space transcends the fate of Tlaloc as embodied in a massive stone monolith discovered in San Miguel de Coatlinchan, Mexico.Since the first years of the twentieth century, historians have disputed the sex of the monolith that was discovered in Coatlinchan. At the center of the debates are the studies by Alfredo Chavero, who identified the stone sculpture as the female goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, and Leopoldo Batres, who refuted this theory and insisted that it is the male divinity Tlaloc. For more information, please see Leopoldo Batres, Tlaloc? (Mexico City: Imprenta Gante, 1903); and Seonaid Valiant, Ornamental Nationalism: Archaeology and Antiquities in Mexico, 1876–1911 (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2018), 173–81.The colossal stone in 1964 was removed by the Mexican government and transported twenty-five miles from its original site to Mexico City amid torrential downpours (despite the dry season) that further enhanced belief in Tlaloc’s mythological prowess as the god of rain. A technological marvel, archaeologists and engineers worked together to lift and tow all 167 tons of the 23-foot-tall monolith to its new home at the entrance of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, an architectural landmark designed by modernist architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez.For more on Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, see Luis Castañeda, “Pre-Columbian Skins, Developmentalist Souls: The Architect as Politician,” in Latin American Modern Architectures: Ambiguous Territories, ed. Patricio del Real and Helen Gyger (New York: Routledge, 2013), 93–114.

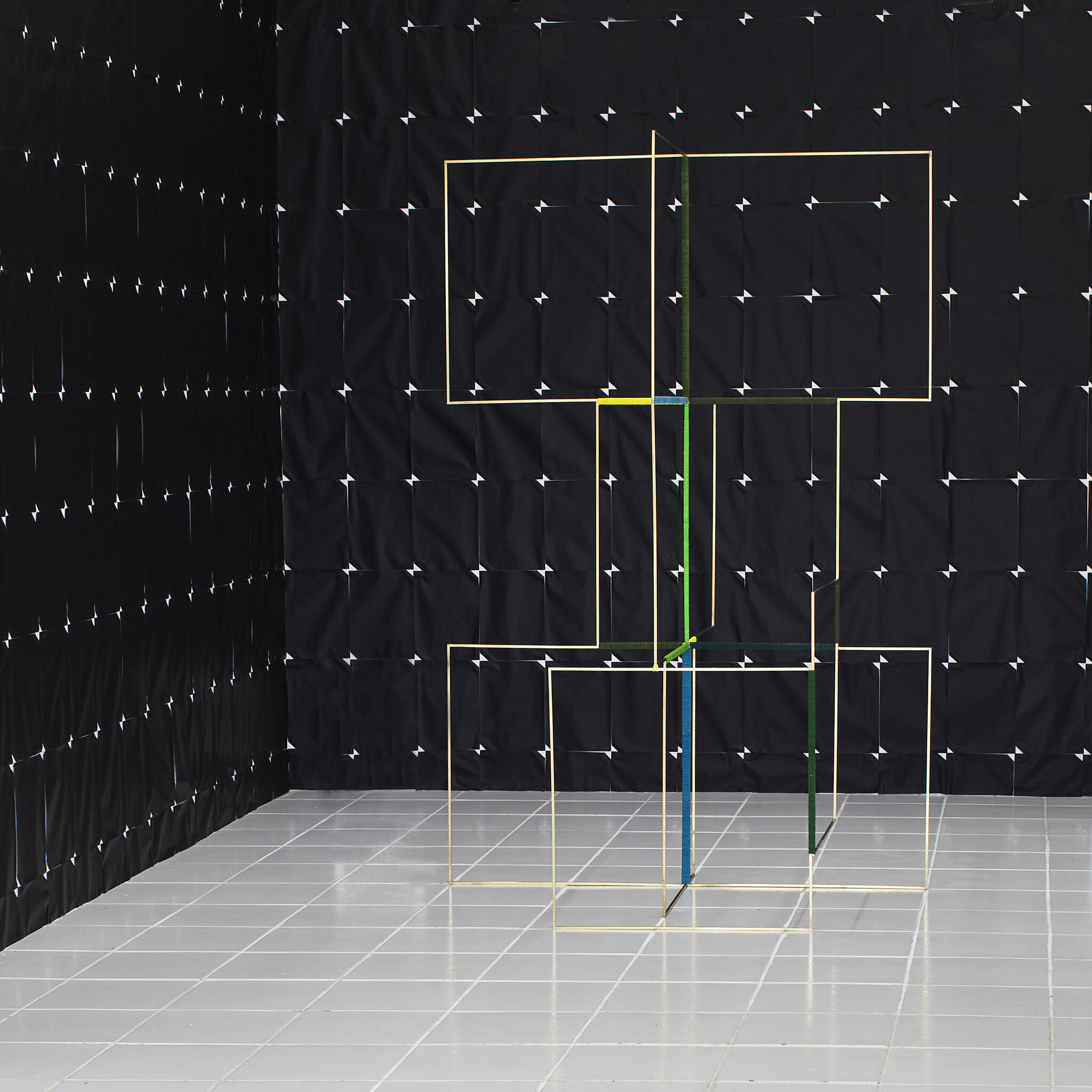

This collision of contexts can be seen in the angular forms Peña Salinas gives to her gender-queer deities. In Tlalicue (2017), for example, the artist renders the shape of the monolith of Tlaloc with undeniable accuracy using thin brass bars held together by blue and green thread. She situates the work and other sculptures in a floor arrangement that evokes a private chamber—an otherworldly space one is invited to enter, not settle or colonize. For each of her sculptures, the artist makes portmanteaus that combine the names of both Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue with the suffix that denotes a place name in Nahuatl (-can). With her streamlined geometric shapes enveloped in colors and housing animals such as frogs and owls that are associated with the gods, the artist claims a space for myth and history to coexist.

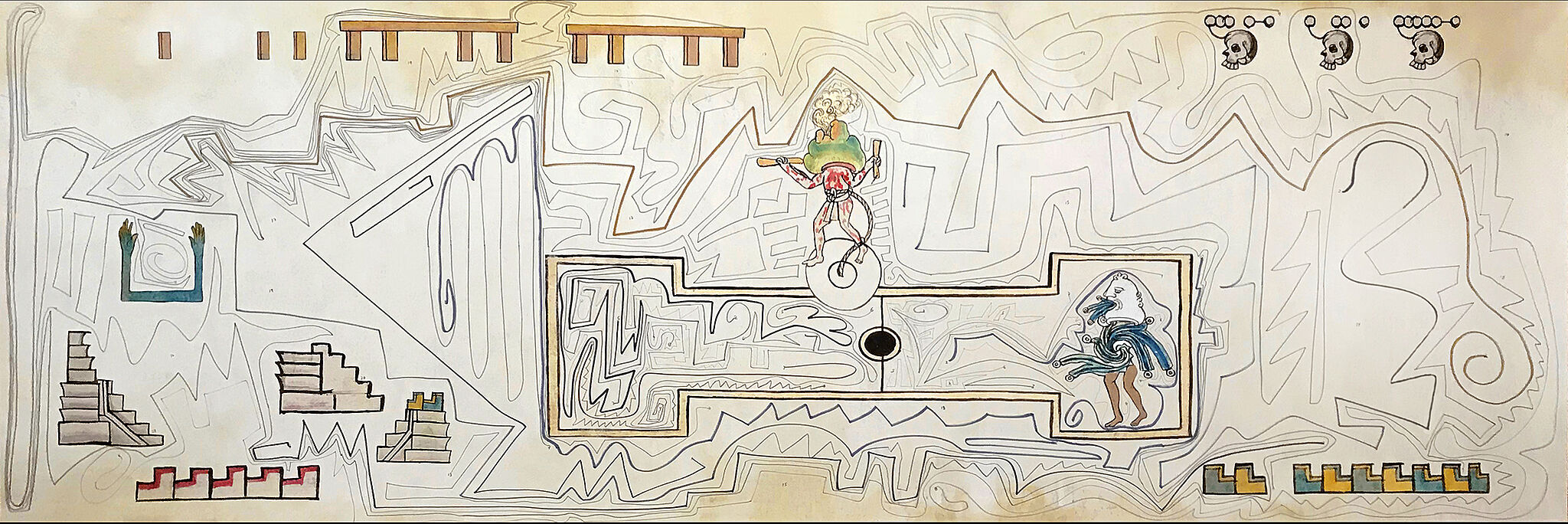

Calling attention to Indigenous languages such as Nahuatl and Quechua is a thread that runs through the practice of many of the artists in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay. With 1.5 million speakers concentrated in central Mexico, but also in the United States as a result of migration, Nahuatl is one of the living Indigenous languages with the biggest presence in the Americas. The use of this ancient language as a tool to chart the history and migration paths of the Mesoamerican people who lived in central Mexico is a key feature of the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, a colonial codex kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.I am using the verb “kept” here deliberately to drive home the point that books such as this one should live among the descendants of the people whose history these manuscripts were explaining. This small rhetorical gesture is my way of arguing in favor of the repatriation of codices, artifacts, and artworks that belong in the Americas and not in Europe.The sixteenth-century manuscript, written entirely in Nahuatl, is the foundation for Guadalupe Maravilla’s series of drawings titled Requiem for my border crossing (2016–18), particularly his works’ maps and pictographic representations. Boldly choosing the elements of the book that serve his narrative and aesthetic and erasing those that do not, Maravilla (b. 1976) digitally manipulates the maps by reconfiguring and collaging the pictographs. He also empties the maps of text to make space for the inscription of his own history, a saga shared by thousands of Central American immigrants.

Maravilla last year changed his name from Irvin Morazán; he readopted the name he was given at birth (Guadalupe) and took as a last name the pseudonym (Maravilla) that his undocumented father used when he crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. In his works, he creates his own mapping system based on sharing, empathy, and a profound belief in elevating the immigrant experience. For the drawings, Maravilla pairs with someone with a similar story as his own: Maravilla crossed the border when he was eight years old aided by a coyote.In this context, a coyote is a person who smuggles migrants across the border between Mexico and the United States, usually for a hefty fee.Together, the artist and his collaborator play Tripa Chuca (which roughly translates to “dirty guts”), a popular Salvadoran game that consists of drawing pairs of numbers in random places all over the paper. Each player then takes a turn connecting one number to its twin by drawing a line, but without touching or intersecting the previously drawn lines. What results are richly drawn illustrations with redux pictographs from the sixteenth century standing in for maps charting the immigrant experience. The link between the Nahuatl-written book and the collaboration with recent immigrants offers an alternate narrative to the vitriolic and offensive discourse often directed toward those who cross the border, and upraises their modest histories to the status of a classic epic.

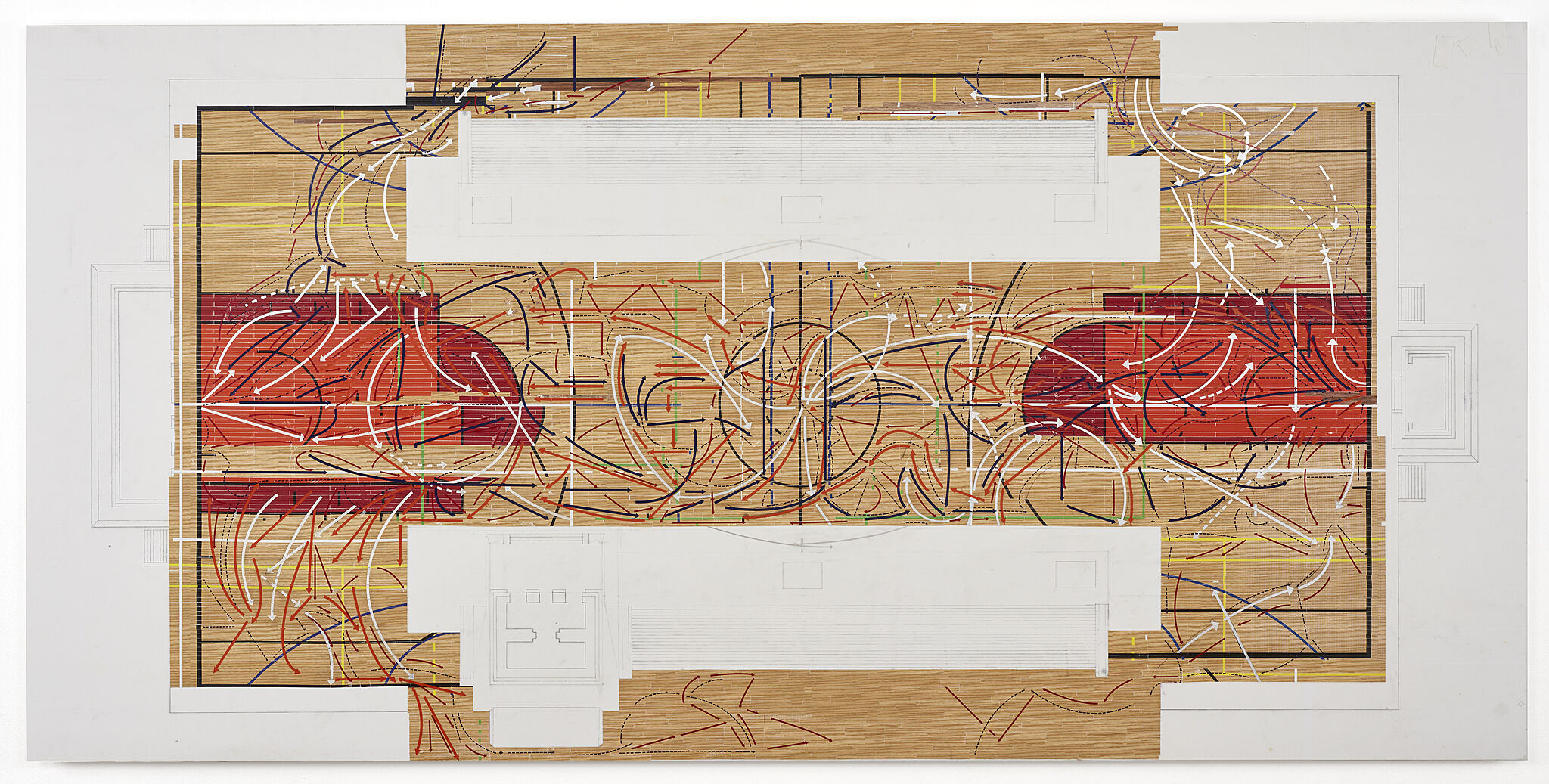

Ronny Quevedo’s mixed-media works and sculptures also combine the lightheartedness of games with references to uprootedness and migration. In works such as Ulama-Ule-Alley Oop (2017), Ulama Ule Olé (2012), and Errant Globe (2015), Quevedo (b. 1981) bridges ancient traditions and contemporary culture through his exploration of sports. Specifically, the artist is inspired by the ball game ullamaliztli played by the Maya, Aztecs, Olmecs, and other groups that can be seen as the precursor to sports such as soccer and basketball. Still played to this day in places such as Sinaloa, in northwest Mexico, and abbreviated to ulama, the sport consists of striking a rubber ball with the hips, buttocks, forearms, or knees, and attempting to score by passing the ball through stone circle hoops jutting out from the sides of a court.For more information about the sport, see Vernon L. Scarborough and David R. Wilcox, eds., The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 1991.This Mesoamerican game was played in a long rectangular court, the shape of which serves as the starting point for many of Quevedo’s works and informs the layout of his dedicated space in the exhibition.

Not unlike Maravilla, Quevedo seeks to bring the daily life of Latinx people into the sphere of art. He honors simple and humble materials readily available in the households of everyday people by extricating them from their original purposes. This is how a modest drawing made with printed adhesive vinyl and resembling the hardwood flooring of a modern gymnasium, as in the case of Ulama-Ule-Alley Oop, enters the discourse of art by tying the past with the present. Key aspects of Quevedo’s biography add context to the works, but the semiabstract and completely abstract drawings exist on their own terms. The allusion to ball courts and soccer, for example, recalls his father, a professional soccer player in Ecuador and a referee in an amateur league in New York when the family moved to the Bronx in the early 1980s. The short strips of adhesive paper in different colors, which later become embossings on wax paper, meanwhile may depict the movement of players across a soccer field, a gymnasium floor, or constellations of stars that can serve as guideposts for migrants’ journeys.

Artist william cordova (b. 1971) also seeks to highlight the ingenuity and resilience of ordinary people by focusing on their use of Indigenous buildings. His huaca (sacred geometries) (2018) removes the patina of grandiosity that often accompanies pre-Columbian ceremonial buildings that have become popular tourist sites. Rather than reinforcing the image of the Ichma temples as pristine and uninhabited that is promoted in his native Peru, cordova chooses to recognize the entropic nature of these ancient structures and the ways in which local people have adapted them for their own modern use. For his site-specific installation, cordova was interested in addressing Huaca Huantille, an Ichma temple located in what today is the Magdalena del Mar district in Lima. Over time the temple had become occupied by squatters, who built makeshift dwellings from simple wooden planks. The humble constructions resembled scaffolds, the very same structures the government would use when it refurbished the temple and declared it a national historic site, thereby displacing its local inhabitants. The installation by cordova, the main element of which also resembles the scaffolds of Huaca Huantille, thus reasserts the utilitarian aspect of pre-Columbian buildings, underscoring that the edifices were built—and were meant to be used by—real people.

Orbiting his installation are randomly scattered gourds, hard-rinded fruits that can at once provide nourishment and serve as vessels for water and other liquids. Gourds figure prominently in the African American imaginary, as in the folk song “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” Essentially another term for the Big Dipper, the Drinking Gourd was the constellation enslaved people used to guide them northward during the night as they fled southern plantations in search of freedom. It is an important component of all of cordova’s work to expound on the metaphysical connections that link the Global South;The Global South is a term stemming from postcolonial studies that has come to replace concepts such as the “Third World” or “developing countries.” Rather than emphasizing the economic disadvantages that affect many southern countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, “Global South” focuses on the colonial and neoliberal conditions that have kept many southern countries and southern regions, as in the United States, in similar states of poverty, disenfranchisement, and underdevelopment.the gourds bring together the material culture of the Andes with African American folklore.

The stainless-steel gate positioned at the side of huaca (sacred geometries) is also a multilayered allusion. It implies a portal or window onto a dimension where vernacular traditions can cohabit and synchretism is possible. The design pattern of the gate resembles Haitian vodou vèvèsA vèvè is a ground drawing made with chalk and used in vodou ceremonies to invite the loas, or divine spirits.and recalls the long history of wrought-iron work in the fences and window bars that protect homes in the Caribbean and southern United States. The stainless steel, however, references the materials used in the architectural designs of Bauhaus-trained immigrants who came to the United States and Latin America in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.See Daniel Balderston, Mike Gonzalez, and Ana M. López, eds., Encyclopedia of Contemporary Latin American and Caribbean Cultures, vol. 1, A–D (New York: Routledge, 2000), 152.The installation, set atop the Whitney’s Renzo Piano–designed open terrace, is a non-monument to pre-Columbian architecture, modern building techniques, modest construction materials, and the vernacular traditions of ordinary Americans.

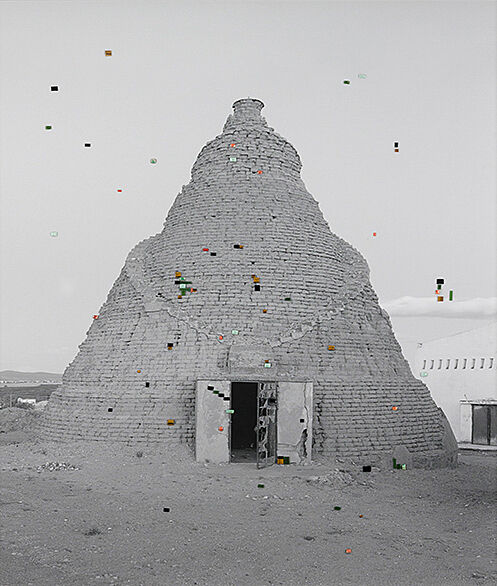

Common and improvisational methods of construction are also ennobled in Livia Corona Benjamin’s body of work inspired by the more than four thousand grain silos built throughout Mexico between 1965 and 1999 as part of a government program to promote small-scale agriculture. Corona Benjamin (b. 1975) turns an investigative eye to the role government plays in urban and rural planning and design, and how the resulting architecture performs in society. In her photographs, paintings, and video in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay the artist looks specifically at the agricultural initiative Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares, better known by the acronym CONASUPO. The goal of CONASUPO was to regulate the price of corn and spur economic growth by guaranteeing that corn raised by local ejidatarios, or small shareholders of land, would be purchased. Farmers needed silos to store the grain for sale, so the government provided them with a blueprint designed by famed Mexican modernist architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez (architect of the Museo Nacional de Antropología), from which they could build their own structures with materials they had at hand. The silos that Corona Benjamin has captured vary but the general shape is always the same: a conical structure with an entrance at the base and sometimes a window on top.

The buildings, which resemble small pre-Hispanic pyramids, had never entered the realm of art until Corona Benjamin photographed them. This lack of interest or awareness finds an echo in anthropologists Christina T. Halperin and Lauren E. Schwartz’s description of vernacular architecture: “Common peoples’ homes and buildings are so ubiquitous and omnipresent that we sometimes fail to ‘see’ them, to think about their variation, to appreciate their technology and aesthetics, and to consider the relationship between architecture and the people who construct, inhabit, and utilize them.”Christina T. Halperin and Lauren E. Schwartz, eds., Vernacular Architecture in the Pre-Columbian Americas (London: Routledge, 2016), 3.Corona Benjamin aims to do the opposite with her photographs of the silos: she amplifies what at first may be a simple curiosity about the form of these structures by employing different methodologies and mediums.

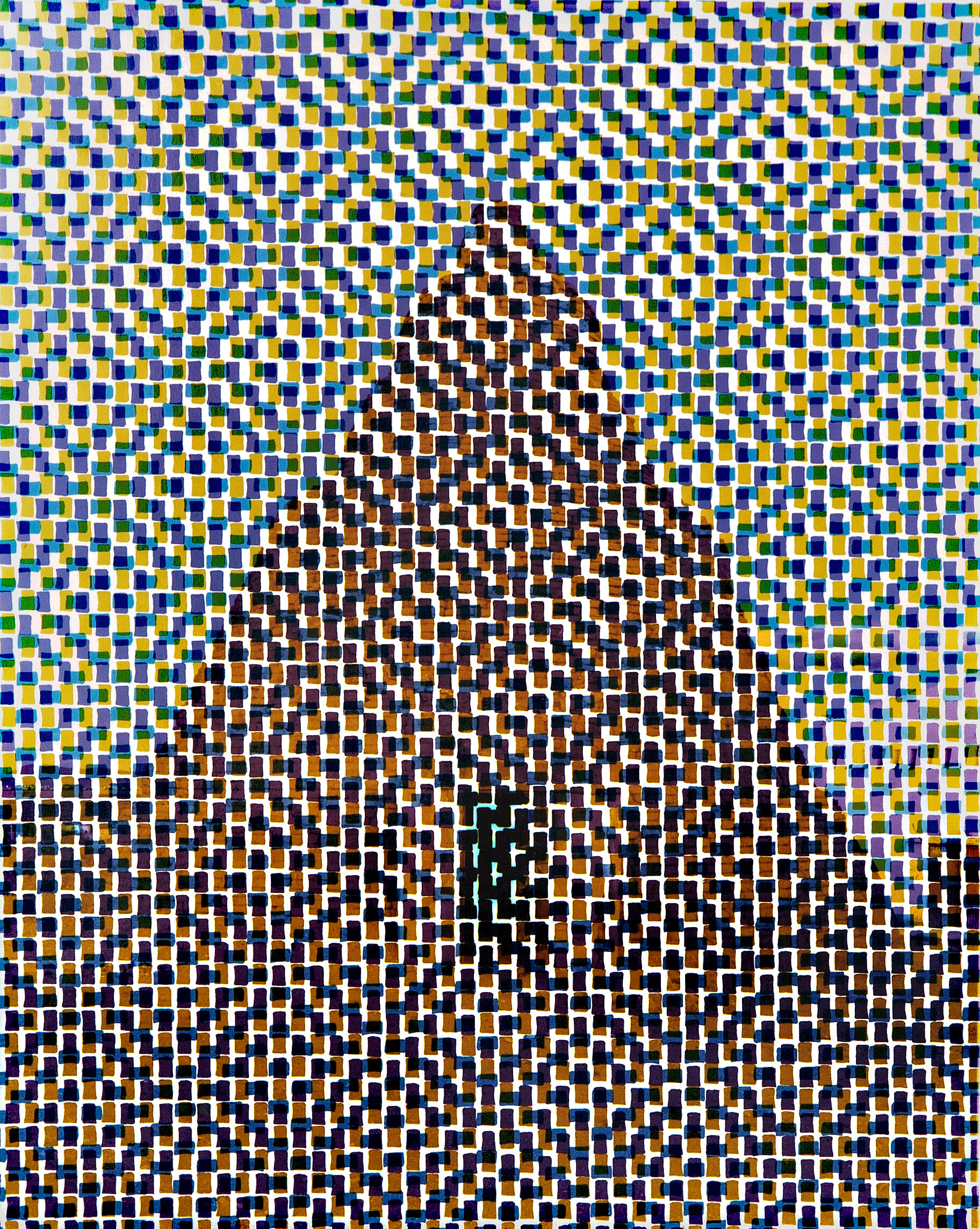

In addition to straightforwardly documenting the thousands of silos built throughout Mexico, the artist has focused on a single negative of one of the silos for her series Infinite Rewrite (2016–18). Alluding to the use of a single master template for the construction of many versions of one building, Corona Benjamin reproduces the same negative but plays with the exposure in a darkroom. Each exposure fractures the image further, generating ranges of color not present in the original negative and resulting in pixel-like shapes that are analog yet give the appearance of having been digitally manipulated. The relationship between the original and the copy responds to a larger concern in her photographic practice and what she sees as the tension between analog and digital photography, while the repetition of the abstract forms nods to the many versions of the grain silos.

In another photograph, Mazatlpilli (2018), the artist places real jewels on top of a print; the gemstones both act as pixels and recall the bricks used for silos. In a new series of works debuting in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay, Corona Benjamin combines black-and-white photographs of different silos with paintings of their current floor plans. No longer fulfilling their original purpose, these buildings have been reinvented according to the needs of the communities around them. Repurposed as houses, schools, motels, and churches, the floor plans point to the ever-evolving creativity of the people who inhabit the structures. Corona Benjamin punctuates her presentation at the Whitney Museum with her video Graneros del Pueblo/Nadie Sabe, Nadie SupoThe title borrows partially from a rhyme popular among those affected by the decline in the government program: nadie sabe, nadie supo, qué fue de la CONASUPO (nobody knows, nobody knew, what became of CONASUPO).(2016), which documents the failure of the CONASUPO agricultural initiative and its financial and cultural impact.

Inspired by the vernacular floor plans revealed in Corona Benjamin’s work, the exhibition design for Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay has at its center a crooked or off-kilter cross—a bastardization of the cruciform plan inherited from Christianity through colonialism. Most of the artists’ spaces radiate from the core of this plan, with the area near the east-facing windows dedicated to Jorge González’s installation titled Ayacavo Guarocoel (2018). The proximity of his work to the native flora that inhabits Manhattan’s High Line, and that literally brushes against Renzo Piano’s building, is the perfect setting for González’s presentation focusing on Puerto Rico’s Taíno and local practices in art and architecture.

González’s title Ayacavo Guarocoel translates as “let’s meet our grandfather,” a phrase taken from Fray Ramón Pané’s fifteenth-century book An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians. The metaphor for seeking knowledge from older generations is apt for a project that incorporates several traditions in a shared space of learning. González’s installation takes as a point of departure the educational environment envisioned by German-born architect Henry Klumb with his wife Else Schmidt and the local people who worked for him, such as his gardener Agustín Pérez, whom González met in the early 2010s.

A protégé of Frank Lloyd Wright, Klumb arrived to the island in 1944 and quickly became the architect synonymous with modern Puerto Rico.In her unpublished essay commissioned by TEOR/ética, an alternative space for contemporary art in Costa Rica, titled “Conciencia tropical: el valor de lo vernáculo” (Tropical Consciousness: The Value of the Vernacular Idiom), Marina Reyes-Franco provides an excellent reading of Jorge González’s practice as well as a summary of Klumb’s experience working for the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, the organization under which he designed a presentation of Indigenous art for the Golden Gate Exhibition of 1939 in San Francisco and an exhibition titled Indian Art of the United States at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1941.On the island, Klumb designed several government buildings as well as residential ones such as his own home, Casa Klumb (1947), where he often exchanged ideas with Schmidt (a weaver), Pérez, and others.Ibid., n.p.His collaboration with craft workers on furnishings, as well as his signature style of modernist architecture adapted to the tropics, serve as the backbone to González’s work. His structures recall those designed by Klumb, not to prioritize the vocabulary of modernism but to emphasize the coexistence in Puerto Rico of traditions that include both the Indigenous and the vernacular. González has folded the recovery of artisanal knowledge into his practice, a gesture that the island desperately needs as it faces an uncertain period of economic and structural recovery from Hurricane Maria. An agent of decolonial thinking, he is focused on bringing forth alternate modes of revaluing Puerto Rico’s ancestral culture.

González has integrated into his installation a sampling of techniques that have been passed down over generations, including the weaving of enea (cattail) that was imparted to him by the Villalobos family from the Cordillera neighborhood in the town of Ciales and the artisan Fernando Torres-Flores from the locality of Certenejas in Cidra. Another “translation,” as González calls it, of knowledge can be seen in the rubbings that Monica Flaherty made of Taíno petroglyphs such as those found in the town of Jayuya in the mid-1950s and the studies that she published about them.Monica Flaherty Frassetto, “A Preliminary Report on Petroglyphs in Puerto Rico,” American Antiquity 25, no. 3 (January 1960): 381–91, see here.Pottery also plays an important role in González’s work, particularly contemporary approaches to Indigenous ceramics. For instance, he is interested in disseminating the studies made in clay by Soraya Serra-Collazo that document the textile impressions left on pre-Columbian cooking plates called burenes. He also collaborates with the Chéveres family, specifically Alice Chéveres, a descendant of the Taíno people who runs a ceramics workshop called Taller Cabachuelas in the town of Morovis. This is of particular significance as it allows people to relearn pre-Columbian pottery techniques, and thus may also preserve these skills for future generations.Reyes-Franco, “Conciencia tropical: el valor de lo vernáculo,” n.p. The collaborative relationships González has developed and nurtured refute the narrative imposed on Puerto Ricans as a byproduct of colonization and instead celebrate their Taíno legacy and ancestral history.

Recognizing the myriad sources of inspiration that González draws from to sculpt a space in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay that reflects both Indigenous and vernacular ideas—and looking back forty years to the Whitney’s presentation of Juan Downey’s The Abandoned Shabono—I am reminded that institutions are not defined by their architecture. This very exhibition, revealing the blueprints of conceptual art concerning Indigenous notions about the built environment as taken up by a younger generation of artists, is testament to the malleability of museums and their function as vessels of ideas. Museums also have the ability to defy temporalities and embody different geographies. Downey likely was well aware of this in his more than two decades of exhibiting his work in the United States, and even if he did not know the term decolonial at the time of The Abandoned Shabono, he probably would have understood the impulse to make visible non-Western systems of thought suppressed by colonization. As Mignolo’s student Michelle K. explained in her catalogue essay for a 2013 international symposium on the topic, the goal of decolonial art is not necessarily to produce “feelings of beauty or sublimity, but ones of sadness, indignation, repentance,” and perhaps most importantly “hope, and determination to change things in the future.”Michelle K., “To my eighteen-year-old self, on your departure for Cambridge, September 21st, 2003.” First conceived for an assignment in Walter Mignolo’s seminar on decolonial aesthetics at Duke University. Reprinted in Decolonizing the ‘Cold’ War, May 19–23, exh. cat., 2013 Black Europe Body Politics, ed. Alanna Lockward and Walter Mignolo (Berlin: Ballhaus Naunynstrasse), see here. The full quotation reads: “And decolonial art (or literature, architecture, and so on) enacts these critiques, using techniques like juxtaposition, parody, or simple disobedience to the rules of art and polite society, to expose the contradictions of coloniality. Its goal, then, is not to produce feelings of beauty or sublimity, but ones of sadness, indignation, repentance, hope, and determination to change things in the future.”