On Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Artists, collaborators, friends, and admirers respond to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s work.

Related exhibition

The exhibition Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map is on view April 19–August 13, 2023

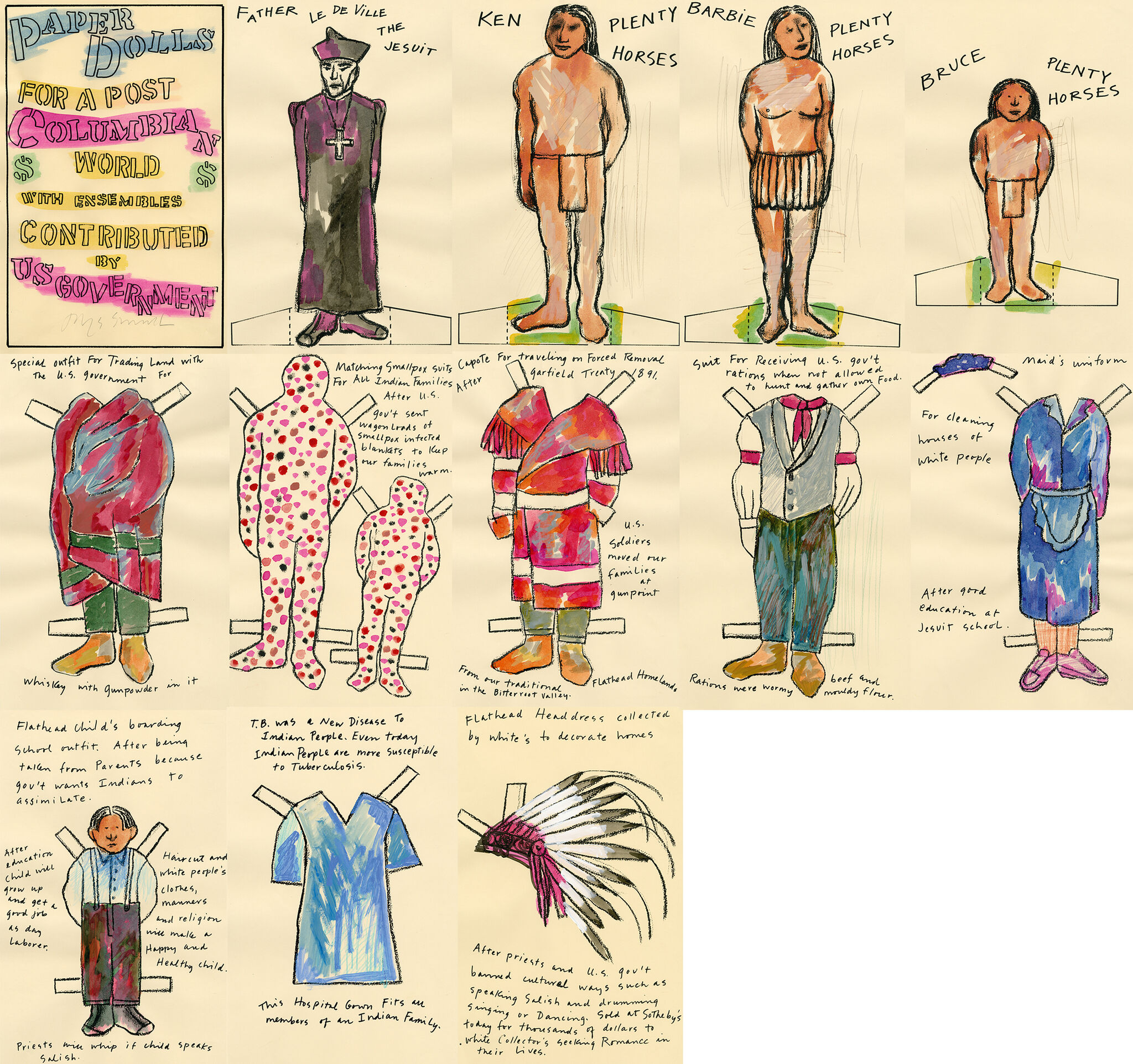

Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World

—Lou Cornum

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s series of paper dolls arises both from an interest in the transhistorical human activity of play as well as the artist’s own family history of boarding school education and domestic labor. There is an almost deceptive whimsicality to Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government (1991). The series title, shaded in lighthearted watercolor hues of blue, pink, and yellow, offers an ironic frame for the works that follow, an irony that troubles more and more as the text interacts with the pencil-drawn images.

The dolls are rendered with a comic strip–like iconography and colored with alternatingly vibrant and muted tones. The first character presented is the Jesuit priest, signaling both the contact between Europeans and the Salish and the nineteenth-century founding of the St. Ignatius Mission in Montana, where the artist was born. The other figures constitute a Native family, their names a combination of a Salish Kootenai family name and those of the most famous of dolls, Ken and Barbie. These references and the money symbols on the title image indicate Smith’s persistent interest in the capitalist mode of exchange and its damaging effects for Indigenous peoples and their lands.

Who gets to play and who has to work? The Flathead child’s boarding school outfit tells part of the narrative of the conscription of Native people—first into religious education and then into “good” jobs as day laborers. The sting of the qualifier “good” is echoed in the maid’s uniform, perhaps to be donned by Barbie Plenty Horses after her “good education at Jesuit school.”

As the paper doll series illustrates, play is a space for rearranging our identities. In the United States, children and adults alike often delight in appropriating Indigenous dress to feel exotic and free. Smith reappropriates the appropriators, using the dolls to relay a dark story dripping in sarcasm. The final image, a headdress, represents one collected by white people and sold for thousands of dollars at auction. While the headdress is desired, the matching smallpox costumes in this series, it can be assumed, would not be so readily adopted as a desirable costume. The cutting humor in these works does not overshadow the historical facts mentioned—including the nineteenth-century Garfield Treaty that ultimately forced the Salish onto the Flathead Reservation in 1891—but like the bright pinks throughout the drawings, Smith’s sardonic twists of phrase and image revel in the ability of Native peoples to both address and reinvent colonial conditions not of their making.

Tricksters

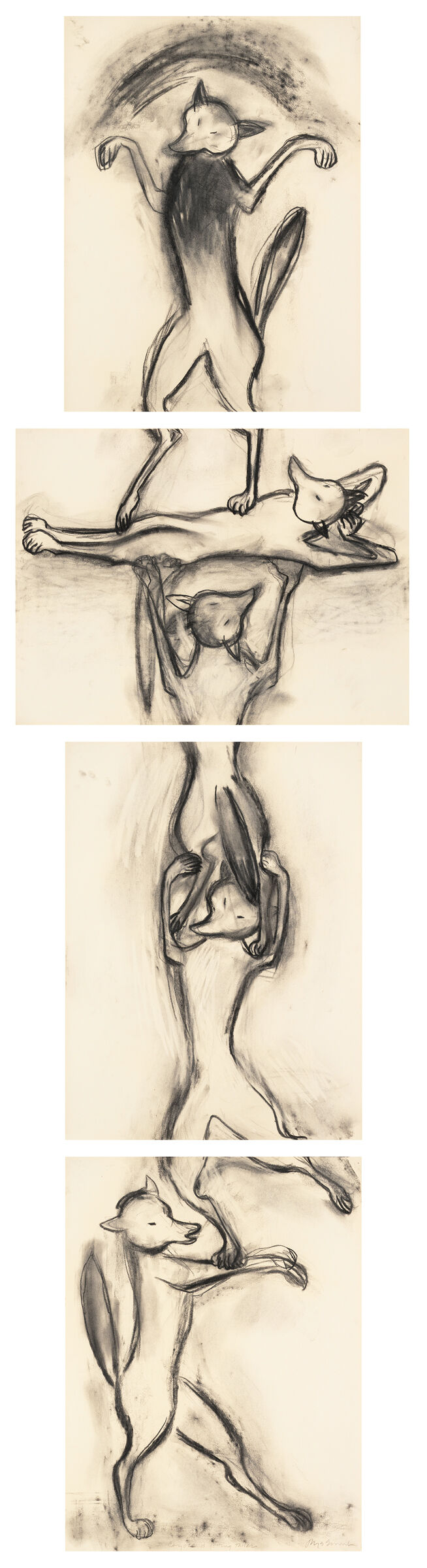

—Larry McNeil Xhe Dhé Tee Harbor Jackson

From a tribal perspective, tricksters were probably accompanying the people migrating to the Americas thousands of years ago. Coyote emerged from the forest, loping along beside the people, teasing them about their crude dogs, who were not as smart or beautiful as them. Coyote brazenly asked the people, “Why do you bring along such crude animals who bark mindlessly and smell bad?” The head dog stopped barking and stepped forward to address Coyote. “Coyote, why would you insult us before we have even been formally introduced?” Coyote said, “Can you stand back a few feet? You smell really bad, Cousin.” The dogs started barking wildly. Coyote laughed and loped back into the forest, and to this day, dogs still bark whenever they hear Coyote.

It is not that Coyote is rude, she and he just speaks freely, especially when witnessing peculiarities, injustices, inequities, or nearly anything that annoys them. Chaos and order are ever present in the universe and if there is too much chaos, Coyote, Raven, or stray tricksters will often intervene. Same with too much order; if things become too regimented or boring, the tricksters may add a bit of chaos to add a sense of balance back to the universe.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith often speaks about her creative process as being meditative and intuitive with stories that cross time. One of her uncanny gifts is that of bringing people together and making things happen. You need to have a trickster on your shoulder to sometimes nudge people along and not think twice about it.

Smith puts on her invisible Coyote persona and politely asks people to change and make things happen, so that makes her a transformer, to stealthily make changes. She is always unequivocal about art having a critical purpose and just like the trickster she is, has a role similar to water in that she blesses nearly every being she encounters, before that water makes its way to the ocean and cycles its way back to the sky and back again. Now that is a suave trickster move, yes ma’am. The beings hardly ever realize how thirsty they were until they become quenched, and that is us in the hot desert sun, getting a gulp of water from the trickster named Jaune, and for that we are grateful all through time, both in ancient times and far into the future. Tricksters earn eternal gratitude, thank you.

The Things She Carries

—Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha)

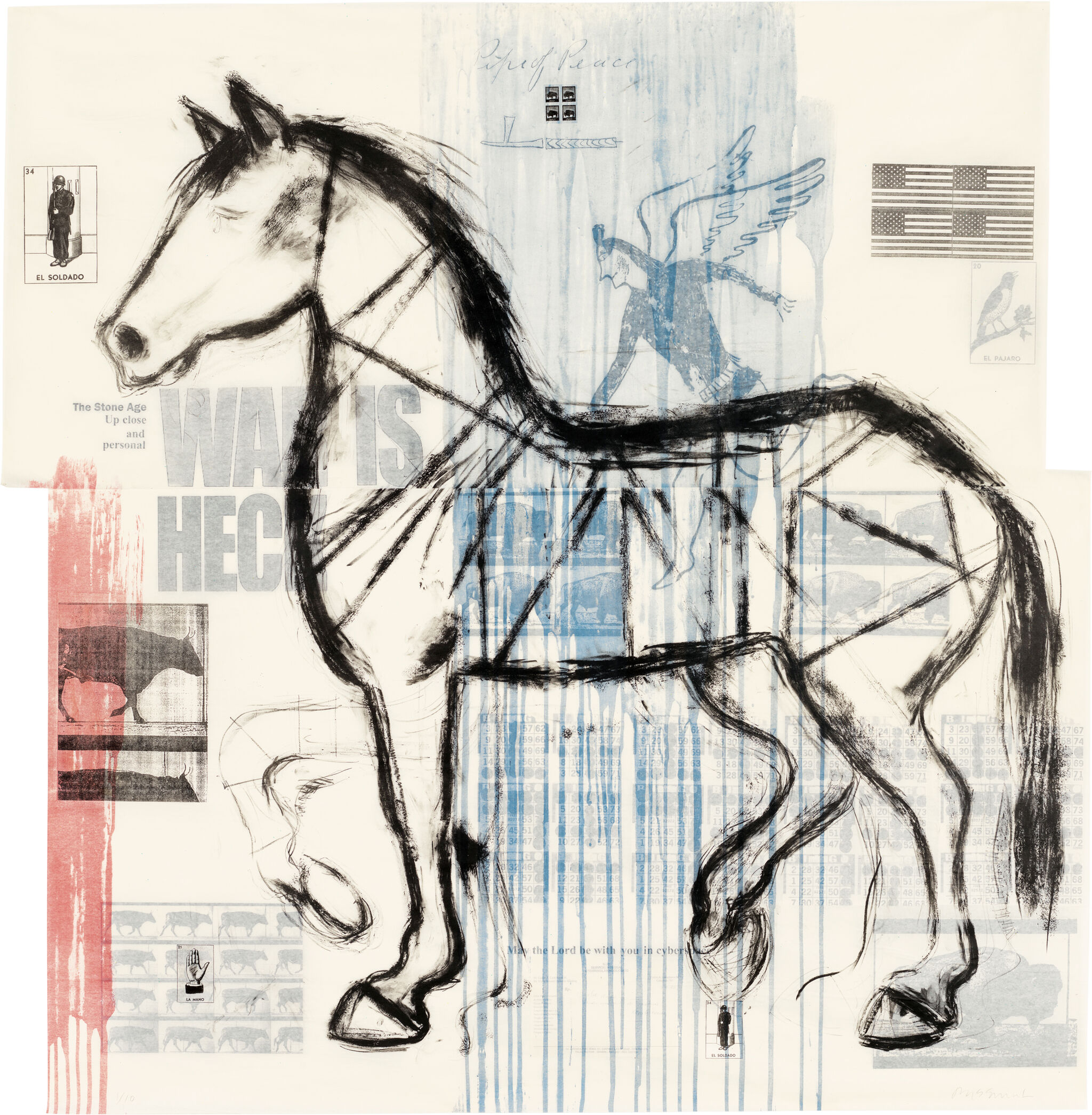

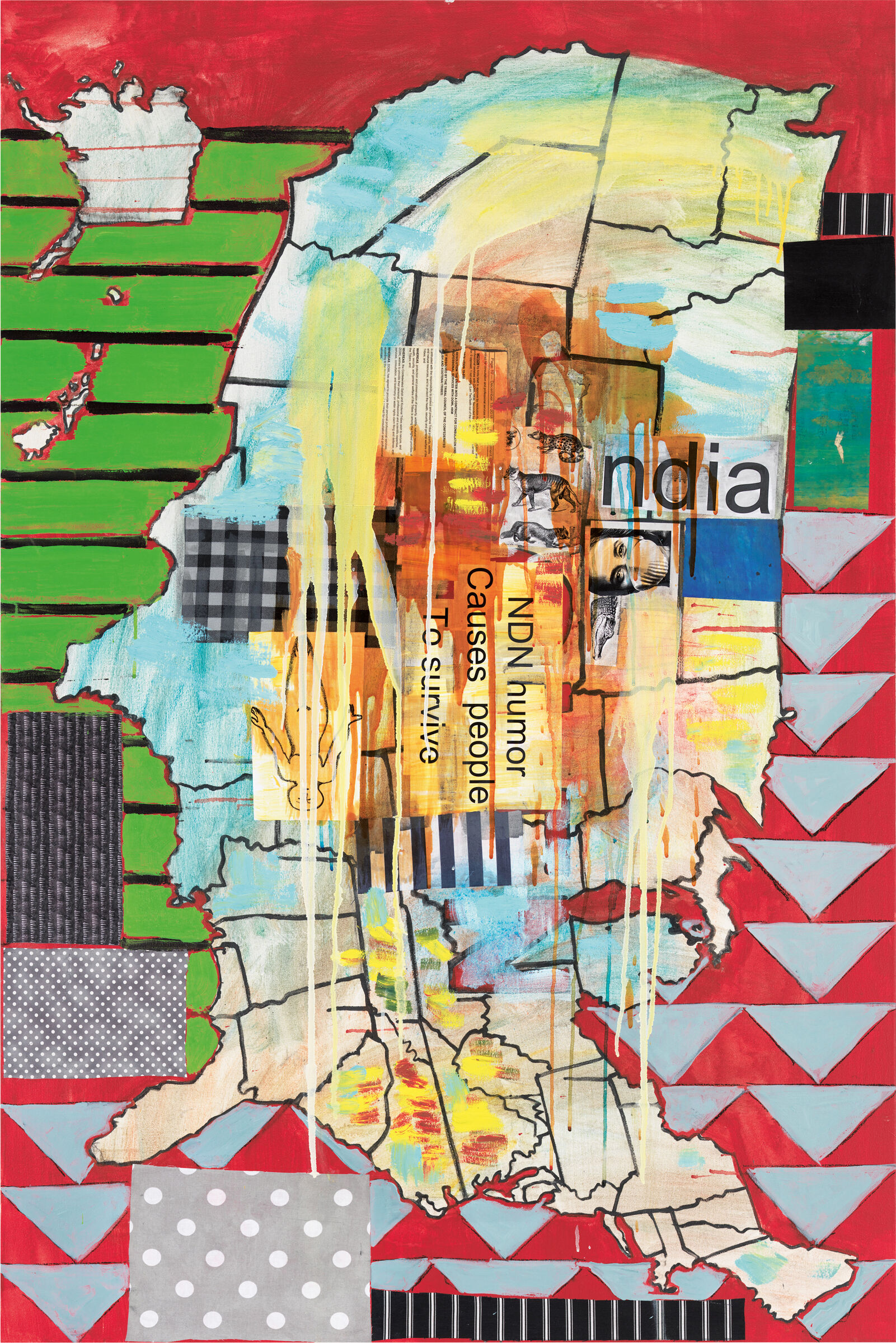

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith was born into conflict. Most Indians are. Smith has known numerous wars: World War II, Korea, Vietnam, three generations of conflict in Iraq, and, of course, numerous iterations of the Indian wars that have never really ended.

For decades, Smith’s visual record has grunted the weight of our violence entangled lives, much like Tim O’Brien’s ragged soldiers in The Things They Carried (1990). Kiowa and his unit trudged through the heat, rain, and mud of Vietnam, every ounce of their lives tucked inside their backpacks: a Bible, a lighter, tattered photographs. They crawled into blackened earth tunnels—crossing their fingers, blessing themselves, hoping to reemerge. Smith’s tunnel is her aesthetic vision, her imagination.

Clamoring with color and honesty, Smith’s images detonate oversize canvases, layered prints, and paper collages. Her materials remind us that war is big, war is repetitive, war is always informed by layers of history and language. Her visual code includes moments of beauty: a butterfly, a small child. Amid the noise, the piles of jutting hands and screaming severed heads, a turtle slowly ascends. These are not valorizations of heroic acts. There is little restraint among war-torn flags and triumphant maggots.

And that hand-hewn canoe with its stern holding steady course past ancient Babylon, Sumer, and Tenochtitlan—that is Smith. Her canoe-self, well read with memory deep, bears our collective traumas in her hull. She journeys ancient waters of the Euphrates, the Tigris, and Indigenous canals. Meanwhile, fleshless Don Quixote still wanders lost in romantic reveries, impossible dreams, chivalric fantasies built upon Brown bodies, desecrated ancestral lands, and poisoned waters.

Contemplating Smith’s wars, my own childhood images emerge: my Uncle Pete and that land mine in the Mekong River Delta. My father, his head down, quietly praying as my brother and I placed flowers on Uncle’s grave one Memorial Day. After, we enjoyed salty grilled meat wrapped in corn tortillas, potato salad, and ice-cold pop. We laughed and played badminton—a paradoxical picnic.

There are people who carry our collective pain and mourning for us so we can move forward. It is a huge sacrifice. Smith’s images bear witness. They are a recounting of truths, creative acts carried out for all of us. She only asks us not to forget, to sharpen our minds, to resist, to remember the impact of the last battle. She reminds us what is sacred. This is a tremendous gift.

Find more entries by artists, collaborators, friends, and admirers in the exhibition catalog Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map.