Approaching a City: Hopper and New York

Kim Conaty, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints

Related exhibition

The exhibition Edward Hopper’s New York is on view October 19, 2022 through March 5, 2023

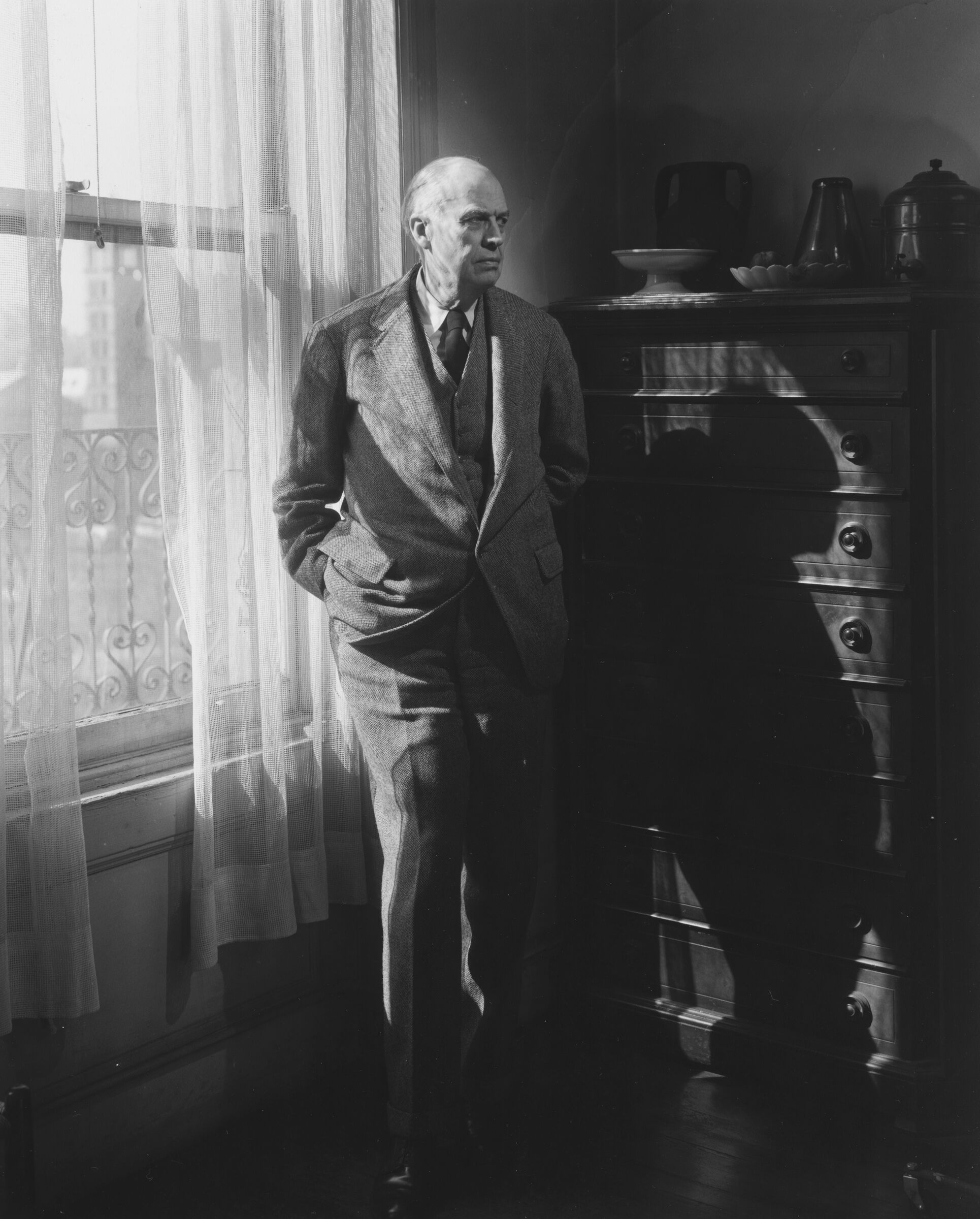

It is 1950 in New York City. In the February morning light, Edward Hopper stands by his window, hands in the pockets of his wool suit, his gaze averted from the camera. He is in his studio, the heart of his modest fourth-floor walk-up residence at 3 Washington Square North, overlooking the park. Formal yet humble, the portrait captures the sixty-seven-year-old artist at the height of his career, mere days after the opening of his largest retrospective to date, at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The photographer, George Platt Lynes, took several pictures of the famously reluctant subject that day, here catching him in a moment of reflection, positioned alongside the domestic trappings of home—a sturdy chest of drawers, a collection of ceramics—rather than the tools of his artistic trade. Through the window, Judson Memorial Church and its attendant campanile can be seen to the south, a view that Hopper depicted once in a then-unfinished painting: “It must have been 15 or 20 years ago. I didn’t finish it. Maybe I will some day.”Edward Hopper, as quoted in “Art: The Silent Witness,” Time (December 24, 1956): 38.

He had lived on the top floor of this brick-faced row house since 1913; the generous windows and skylights helped to expand the space indoors, while the park offered an urban-variety front yard in which to stroll, read the newspaper, think and look. It would remain his home and place of work for more than five decades, during which time his Greenwich Village neighborhood, and the city at large, would experience a period of tremendous urban development, as the artist’s own position grew from relative obscurity to national eminence.

Hopper’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum, located at the time on West Eighth Street, just one block north of his studio, featured more than 170 of the artist’s paintings, watercolors, and prints, a substantial portion of his output to that point.Lloyd Goodrich, Edward Hopper Retrospective Exhibition (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1950). Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 11–March 26, 1950; traveled to Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, April 13–May 14, 1950; and Detroit Institute of Arts, June 4–July 2, 1950.More than half of the paintings on view took inspiration from New York—from early impressions of rooftops to later works in which the city served as a backdrop for evocative distillations of urban experience—an oeuvre that reflected the deep, enduring hold the city had exerted upon Hopper throughout his career. But the reception of the show, which was organized by Whitney curator and the artist’s longtime champion Lloyd Goodrich, revealed Hopper had achieved an appeal that extended far beyond city limits; Life magazine anointed him the “major American artist of the century,” and fellow artist Charles Burchfield described him as “one of America’s most original and powerful creators.”“Edward Hopper: Famous American Realist Has Retrospective Show,” Life, April 17, 1950, 100; Charles Burchfield, “Hopper: Career of Silent Poetry,” Artnews 49, no. 1 (March 1950): 15.In his work, Hopper appeared to capture the experience of living in one of the world’s fastest-growing metropolises in a manner in which change and changelessness could coexist, and New York could reflect both a specific place intensely observed and the broader sensations associated with modern urban life.

“You start building your private New York the first time you lay eyes on it,” Colson Whitehead mused in the introduction to his series of vignettes about city life.Colson Whitehead, The Colossus of New York: A City in Thirteen Parts (New York: Anchor Books, 2003), 4.Indeed, Hopper’s New York was a product of his personal experiences in the city throughout his lifetime, of the particular ways that he engaged with the sites and sensations around him. The painstaking deliberateness with which he absorbed, reflected upon, then refined his impressions—“I’m thinking out my picture,” he once responded to a neighbor who approached him as he sat idly in the park—can be gleaned from his pace of output, which increasingly averaged but two or three canvases a year.Hopper’s remark to neighbor and fellow artist Paul Resika is recounted in Avis Berman, “Unblinking Witness to a Moody Town,” New York Times, March 27, 2005. This article was published on the occasion of Berman’s more extensive study of Hopper and New York, the first publication dedicated to the topic and one that provided important insights for this project. See Avis Berman, Edward Hopper’s New York (San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2005).New York had played a central role in Hopper’s life since his childhood, when he traveled to the city for theater and other outings with his family from their home in Nyack, less than thirty miles north of Manhattan. In 1899 he made the shift from tourist to commuter while attending art schools in the city, and moved there full time in 1908, earning his first paychecks as a commercial illustrator while holding tight to his painterly aspirations. Hopper tried out different neighborhoods, as many individuals do in this city of renters, first living in a studio at 244 West Fourteenth Street and then in an apartment at 53 East Fifty-ninth Street, before settling into his Washington Square perch. Such “settlers,” as E. B. White, renowned chronicler of the city, described this type of urbanite in 1949, were uniquely positioned to “[absorb] New York with the fresh eyes of an adventurer.”E. B. White, Here Is New York (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 18.Hopper certainly did.

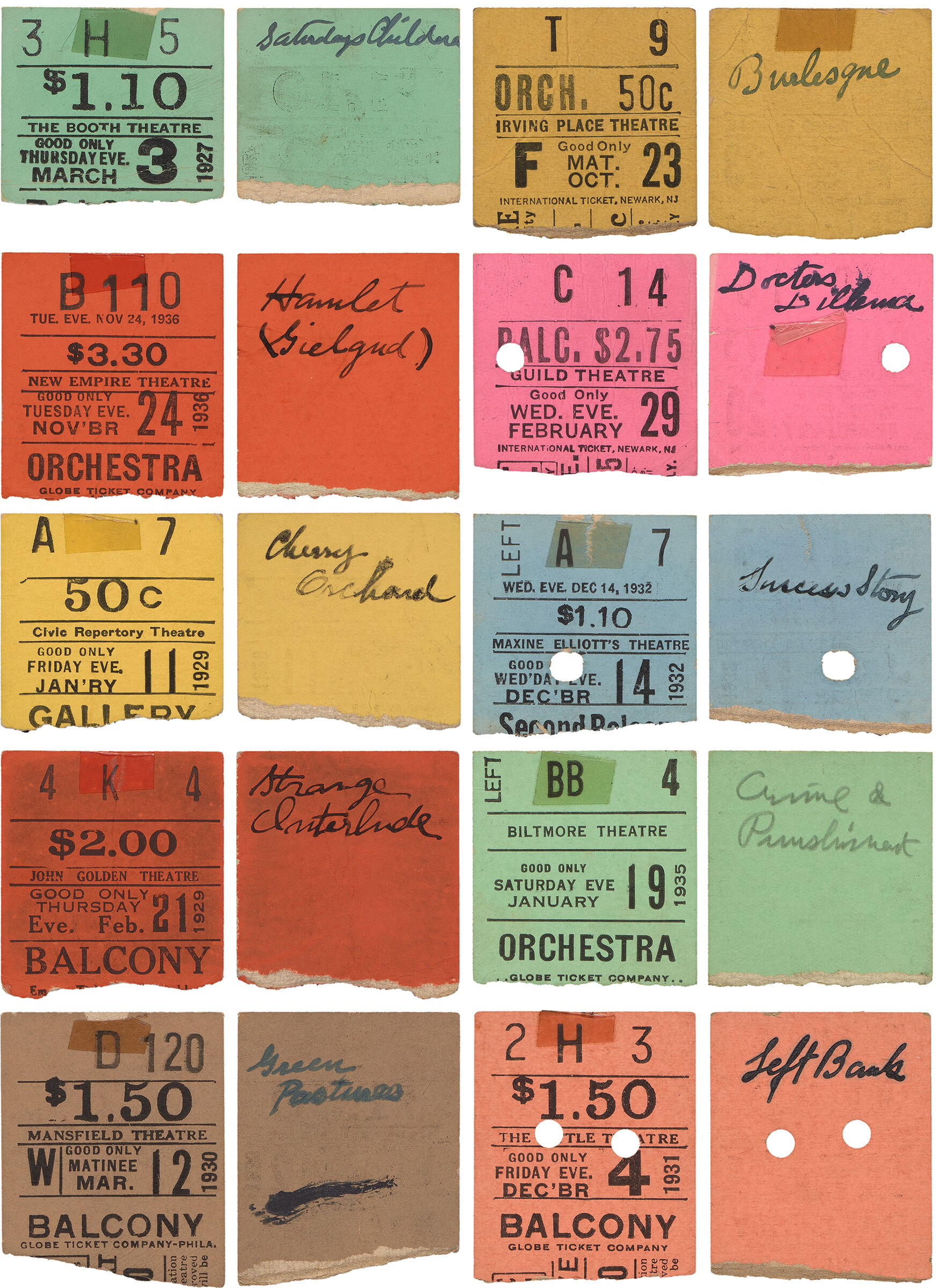

Ironically, it was in Gloucester, Massachusetts, during one of his regular summer sojourns to paint in coastal New England, that Hopper crossed paths with a former art-school classmate who shared his intrinsic devotion to New York. Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivison was also spending the summer of 1923 painting outdoors, away from her apartment in Greenwich Village. The two married the following year—he, forty-two; she, forty-one—and they lived and worked together at 3 Washington Square North for the rest of their lives, decamping during the summers to East Coast destinations like Cape Cod, where they built a home in 1934, or spending several weeks on road trips further afield. Much has been said of the couple’s sometimes tempestuous union and diametrically opposing personalities—his introverted, silent, even stalwart tendencies at odds with her voluble nature (“Some times talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom,” Jo noted)—but they stayed with each other.Jo Hopper, as quoted in William Johnson, “Hopper Cover Research,” unpublished typescript, October 30, 1956, p. 7, Series 4: Biographical and Personal Papers, c. 1894–1968, Subseries 4.6: Interviews with Hopper, Edward and Josephine Hopper Research Collection, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library and Archives, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (hereafter cited as Edward and Josephine Hopper Research Collection).Although each had already begun forging a “private New York,” having lived separate lives in the city for several years, their New Yorks overlapped in significant ways. They both loved the theater and took advantage of the city’s world-renowned offerings, sometimes attending multiple productions together in a single week.The Hoppers’ ticket stubs document more than a hundred theatrical productions they attended between 1925 and 1936; see Series III: Edward Hopper Personal Papers, 1892–1974, Subseries F: Ticket Stubs, 1925–1937, Box 23, Folders 21–59, The Sanborn Hopper Archive at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library and Archive, New York; gift of the Arthayer R. Sanborn Hopper Collection Trust (hereafter cited as Sanborn Hopper Archive).Their shared disinterest in cooking—the apartment’s tiny kitchen alcove would have made boiling water challenging enough—prompted them to eat out frequently and to enjoy the city’s modern conveniences, like inexpensive restaurants, cafeterias, and automats, all of which in turn inspired Hopper’s artistic ruminations.

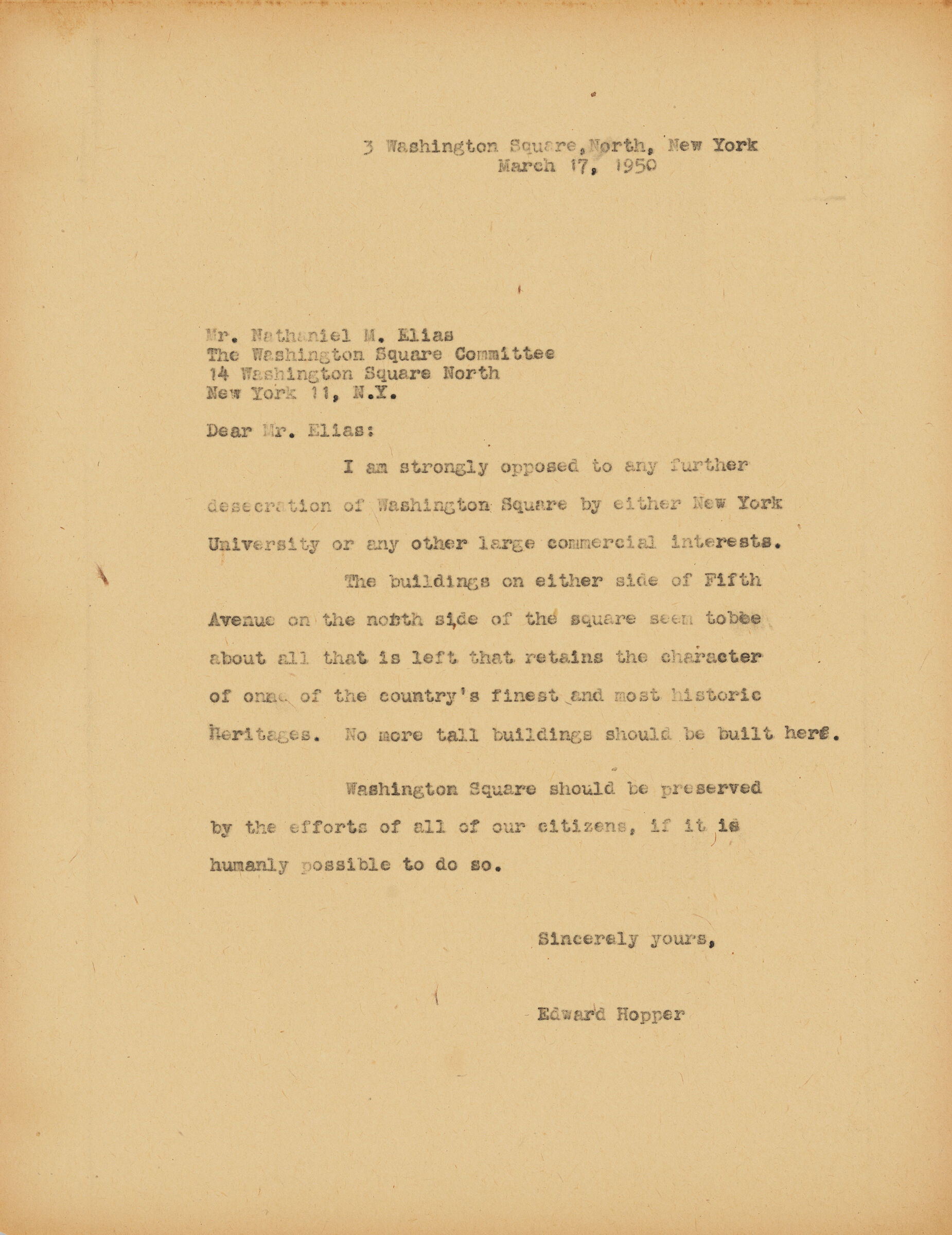

The Hoppers also shared a deep belief in the preservation of the city’s histories, most notably traced through its buildings and most acutely felt in the fear of losing their own. In 1947, they narrowly avoided eviction as they fought against the encroachment of New York University, and the threat posed by development to the residential character of their beloved neighborhood remained an ongoing concern.See Jennie Goldstein, “‘We Are Not Sleeping’: The Hoppers’ Fight for Washington Square,” in Edward Hopper's New York (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2022).In a letter to the Washington Square Committee in 1950, the year of his Whitney retrospective, Hopper argued: “The buildings on either side of Fifth Avenue on the north side of the square seem to be about all that is left that retains the character of one of the country’s finest and most historic heritages. No more tall buildings should be built here.”Hopper to Nathanial M. Elias, March 17, 1950, Series V: Correspondence, 1904–1967, Subseries D: Written by Edward Hopper, 1938–1966, Box 30, Folder 70, EJHA.2072, Sanborn Hopper Archive. The Hoppers had seen countless peers pushed out of their housing as the city made way for the next best thing, from skyscrapers to subway lines. Though their advocacy largely took form on a typewriter rather than on picket lines, they shared many ideals of the growing number of activists whose skepticism of “urban renewal” projects would soon find a powerful voice in the work of Jane Jacobs and her paradigm-shifting Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), in which she advocated for “mingling buildings that vary in age and condition, including a good proportion of old ones.”Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961), 187.

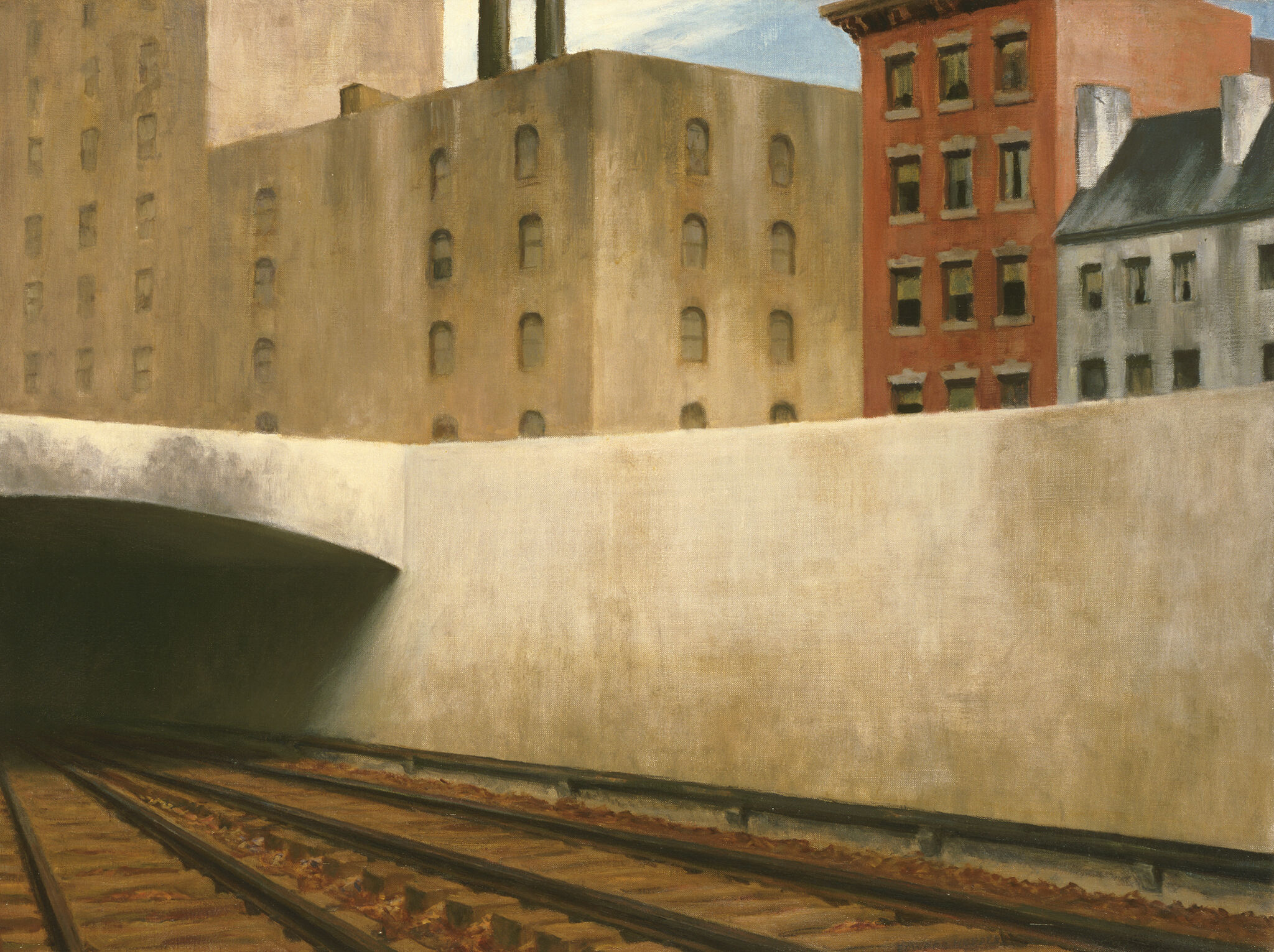

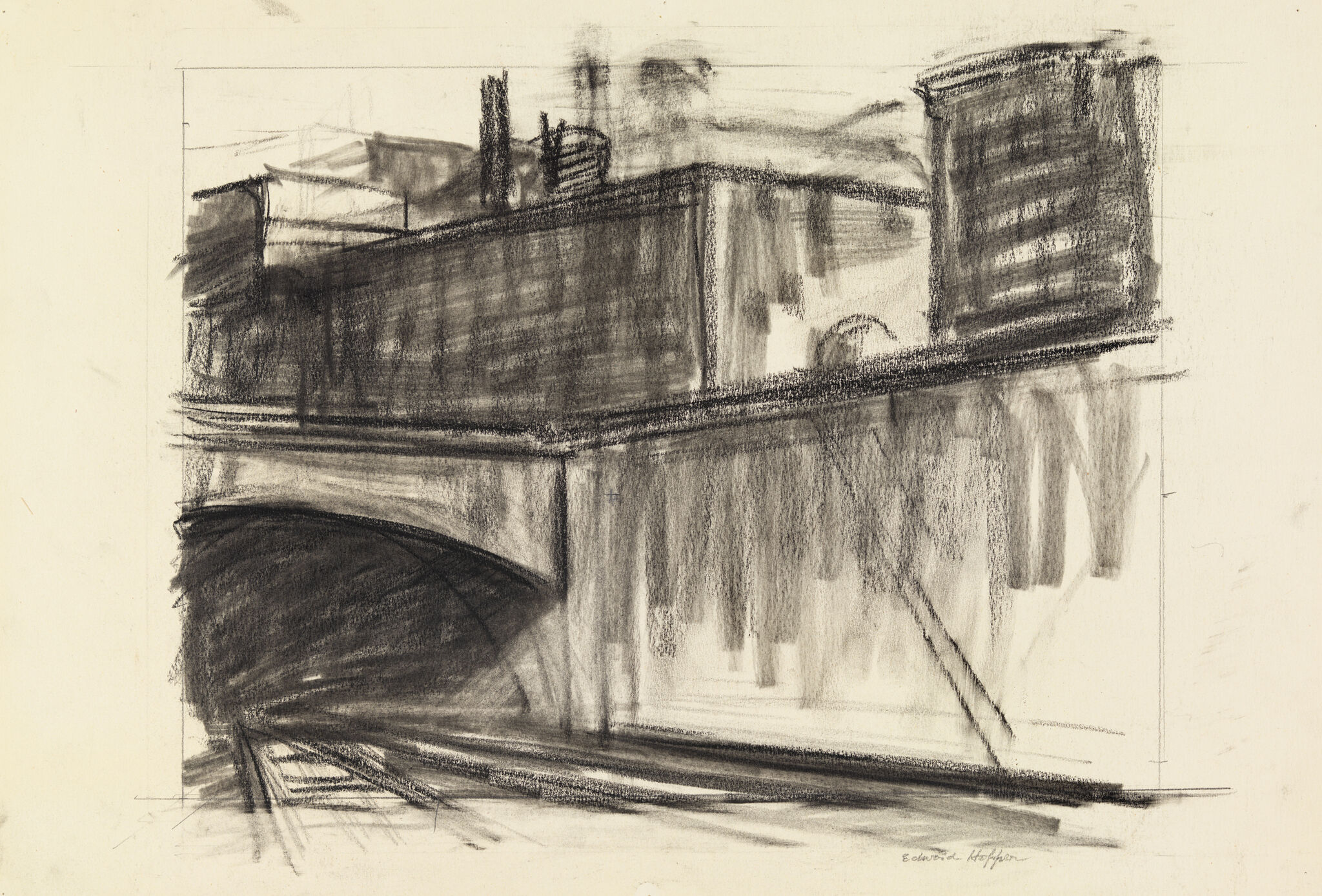

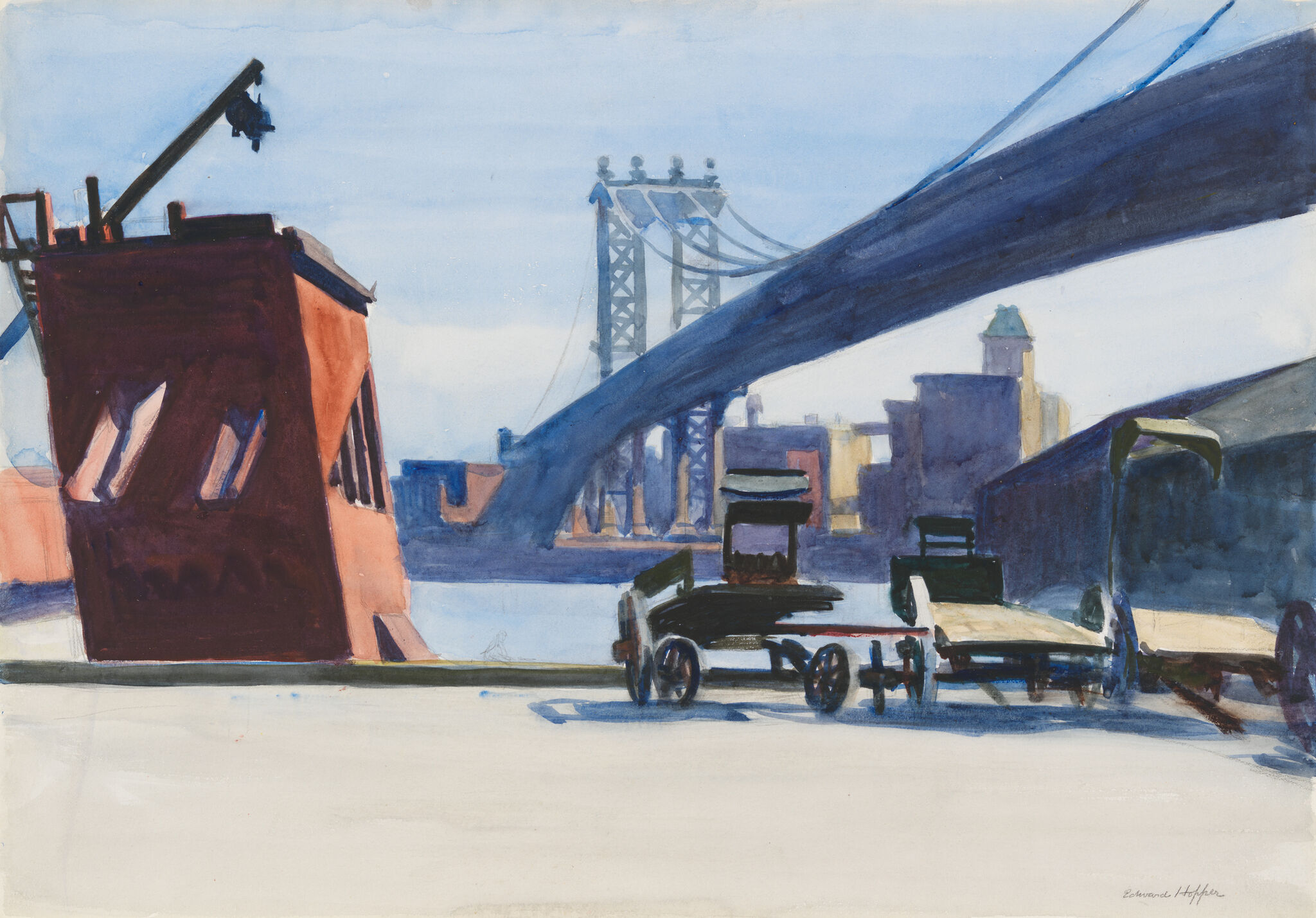

Hopper gave visual form to certain of these ideas in his 1946 canvas Approaching a City, a work that emblematizes the moment of entry into New York without landmarks or fanfare but rather via a stretch of ordinary buildings tightly packed against one another. Throughout his career, Hopper spoke through architecture and gave narrative authority to the common structures and out-of-the-way corners he passed rather than to the iconic buildings and picturesque views many of his artistic peers gravitated to. Here, the building types—from the nineteenth-century brownstone to the modern industrial structure at far left—suggest the passage of time and the histories that coexist, pictured as a single mass of forms seen from the train tracks below. A concrete retaining wall cuts across the center of the composition and blocks the bottom portion of the buildings above, where details like street numbers and storefront signage are suppressed from view. The looming dark tunnel amplifies the sense of the unknown or unknowable ahead, creating a particular frisson. As Hopper later reflected on this painting: “There is a certain fear and anxiety and a great visual interest in the things that one sees coming into a great city.”Hopper, as quoted in John D. Morse, “Oral history interview with Edward Hopper,” June 17, 1959, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

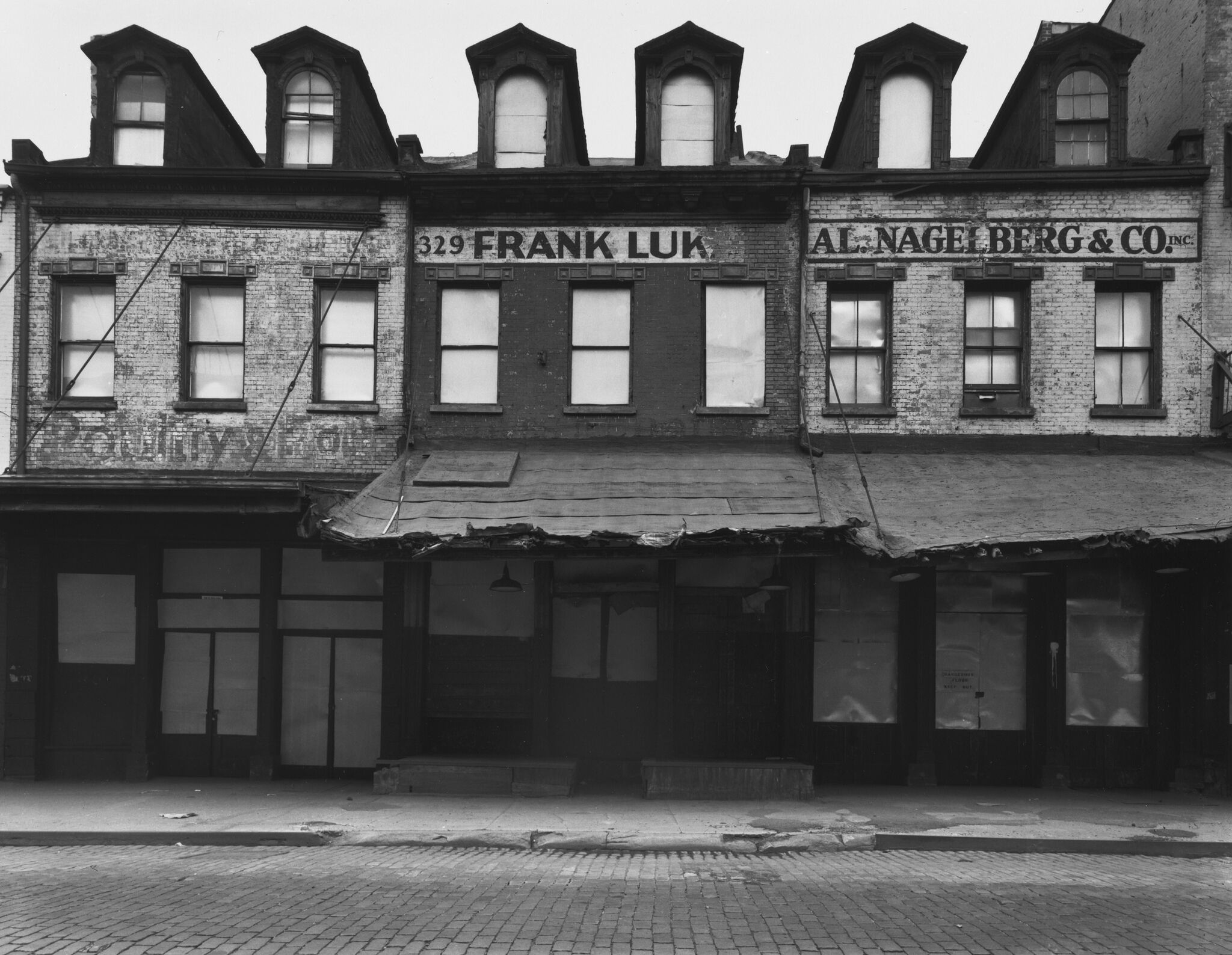

A trip today to the same spot at East Ninety-seventh Street and Park Avenue, where Hopper traveled in January 1946 to make sketches for this painting, delights as much as it perplexes.According to Jo’s diaries, Hopper made his first trip uptown to the site on January 27, 1946, and made four preparatory sketches; see Josephine Hopper, diary entry, January 27, 1946, as cited in Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 388. Carter Foster examined in depth this relationship between Hopper’s drawings and finished paintings in his groundbreaking study Hopper Drawing (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013). Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, May 23–October 6, 2013; traveled to Dallas Museum of Art, November 17, 2013–February 16, 2014; and Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, March 15–June 22, 2014.The basic composition is there: the stretch of buildings, the sunken track, and the dark portal through which commuter trains rush daily, delivering tens of thousands of passengers to Grand Central Station. But unlike the preparatory drawings that documented what he saw, Hopper’s painting offers a personal reflection. You won’t find his buildings along Park Avenue, nor would you have encountered them during his lifetime, as contemporaneous photographs of the site attest. Hopper’s intentions in his painting, as he articulated a few years earlier, were to “project upon canvas my most intimate reaction to the subject as it appears when I like it most; when the facts are given unity by my interest and prejudices.”Hopper to Charles H. Sawyer, October 19, 1939, Archives of the Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts.His work was built from intensive looking but also a highly subjective process of synthesis—on paper, on canvas, and in his mind. Shortly after this painting was made, Hopper further described the struggle he felt between working “from the fact” and improvising, admitting that he often felt “torn between the two.”Hopper, as quoted in Lloyd Goodrich, “Notes of Conversation with Hopper,” unpublished typescript, April 20, 1946, 5, Series 4: Biographical and Personal Papers, c. 1894–1968, Subseries 4.7: Notes and memoirs about Hopper, Edward and Josephine Hopper Research Collection.

Hopper’s choice to depict this moment of passage into the city in 1946, after he had been making such trips for decades, demonstrates a certain reverence he maintained for the powerful sensory experience of entering a city, one that is felt anew each time and yet builds on layers of memories from trips past. This scene may be drawn from New York, but there’s also a tremendous openness generated in the artist’s decision to call it simply “a city.” The ever-renewing sense of mystery and discovery particular to the urban experience can be felt by anyone who, like Hopper, finds themselves explorers on their own turf— getting off a bus stop in a new neighborhood, taking a different side street along a familiar course, or even walking through one’s own neighborhood at night.

One evening, the Hoppers received a surprise visit at 3 Washington Square North from a reporter who, among other things, asked them what they did for fun in the city. “We’re not spectacular and we’re very private, and we don’t drink and we hardly ever smoke,” Jo rattled off protectively. Edward simply replied: “I get most of my pleasure out of the city itself.”Archer Winsten, “Wake of the News: Washington Square North Boasts Strangers Worth Talking to,” New York Post, November 26, 1935, 15.Hopper’s New York is a city that revels in the interplay between urban space and imagination, the city as it existed and as the artist willed it to be.I have taken inspiration here from Rebecca Solnit’s articulation of what make cities matter and what makes them more than just a point on a map. See Rebecca Solnit and Susan Schwartzenberg, Hollow City: The Siege of San Francisco and the Crisis of American Urbanism (London and New York: Verso, 2002), viii.Like millions of fellow New Yorkers before and since for whom the city holds an undeniable magnetism despite its difficulties and disillusionments, Hopper stayed. In his penultimate year of life, Hopper maintained that New York was “the American city that I know best and like most.”Hopper, as quoted in Arlene Jacobowitz, “Interview between Edward Hopper and Arlene Jacobowitz from the ‘Listening to Pictures’ program of the Brooklyn Museum,” unpublished typescript, April 29, 1966, p. 1, Series 4: Biographical and Personal Papers, c. 1894–1968, Subseries 4.6: Interviews with Hopper, Edward and Josephine Hopper Research Collection.And in many ways, his New York resonates still today, in the collective memory of the city’s histories, but no less so in the actuality of lived urban existence.

“You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now.”Whitehead, Colossus of New York, 4.Colson Whitehead’s words again serve to situate Hopper in relation to the always changing city that, still, the artist maintained he “knew best and liked most.” Looking at these works today, it’s hard not to see them as relics of a bygone city. Some of Hopper’s places have disappeared completely—the Circle Theatre has been replaced by the Shops at Columbus Circle; the Sheridan Theatre by a park that is home to an AIDS Memorial. The elevated trains in Manhattan have long been dismantled, save the old freight railway reimagined as a twenty-first-century urban park, the High Line. The neighborhood barber shop, marked by its red, white, and blue pole and patronized by casual walk-ins, has all but been replaced by the destination salon, and the very idea of creating window dressings for a drug store would seem preposterous today: Customers patronizing whichever generic chain pharmacy on any given corner may hardly even bother to look up from the screens in their hands.

Chroniclers of New York up to contemporary writers such as Teju Cole have described the city as a palimpsest, one that is constantly “written, erased, rewritten.”Teju Cole, Open City: A Novel (New York: Random House, 2011), 59.This was as true in Hopper’s time as it is today, a part of city life that one grows accustomed to even if not without a sense of loss. In 1966, the year before Hopper passed away in his Washington Square studio, photographer Danny Lyon began the documentary project that would culminate three years later in the book The Destruction of Lower Manhattan. “I came to see the buildings as fossils of a time past,” Lyon writes. “The passing of buildings was for me a great event. It didn’t matter so much whether they were of architectural importance. What mattered to me was that they were about to be destroyed. Whole blocks would disappear. An entire neighborhood . . . and no place like it would ever be built again.”Danny Lyon, The Destruction of Lower Manhattan (New York: Macmillan Company, 1969), 1.

For all that has changed in the city, its fiber remains, held fast by the millions of individuals who call New York home as well as all those whose lives have intersected with it. When the Coney Island-bound F train emerges from its underground tunnel for a few brief moments between Carroll Gardens and Park Slope, or the Q train trundles over the Manhattan Bridge, you are bound to see more than one passenger take a break from her phone or magazine to gaze out over the passing landscape, not unlike the rider Hopper depicted over a century ago in his House Tops etching. Views from New York’s surrounding waterways have become more common again, as increasing numbers of commuters utilize the city’s expanded ferry system and experience panoramas of the iconic— and still-changing—skyline daily as well as close-up views of the city’s bridges and sites like Roosevelt Island. And when that skyline appears to mutate overnight as another “supertall” skyscraper rises above the rest, one might identify with the complicated emotions of an unpredictable future that Hopper evoked so concisely in Early Sunday Morning, with its looming dark rectangle hovering over a low-slung building. Cities will continue to change; it is part of what makes them alive. Hopper’s work reminds us of this inevitability but also helps to illuminate what remains and what can still capture our imagination, in the quiet moments, out-of-the-way corners, and chance encounters of everyday city life, if we remember to look.