Looking at Mark Armijo McKnight’s Decreation

For his exhibition Decreation, Mark Armijo McKnight invited one of his favorite writers, T Fleischmann, to contribute a reflection on his work. A poet and essayist whose writing defies conventional genre boundaries—often blending memoir, criticism, and poetry into a singular, evocative voice—Fleischmann shares with Armijo McKnight an interest in exploring the intersections of landscape, identity, embodied experience, and the transformative power of art. In their second book, Time is the Thing a Body Moves Through (2019), Fleischmann crafts a poignant meditation on queer community, artistic creation, and the politics of embodiment, weaving together reflections on Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s art and their own personal experiences. The narrative unfolds in fragments, mirroring the fluidity of time and the body’s movement through it. Like their previous writings, Fleischmann’s response to Decreation calls attention to their embodied experience of the exhibition.

—Drew Sawyer, Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography

I go to see Decreation on the early afternoon of September thirtieth. It’s sunny out and warmer than I expected, nearing seventy degrees after a drizzly, cool morning. I’m sweaty when I get to the museum, and I have a slight migraine, set off from the chemicals in an Oreo-flavored Coke that I didn’t realize was zero sugar.

Forgetting that the show is in the free gallery, I pay the Whitney thirty dollars. When I ask which floor to go to, a gallery attendant directs me around the side.

The free gallery is the best part of the museum because of its accessibility. All museums should be like the free gallery.

When I step into the show, it is so beautiful, and I immediately pause.

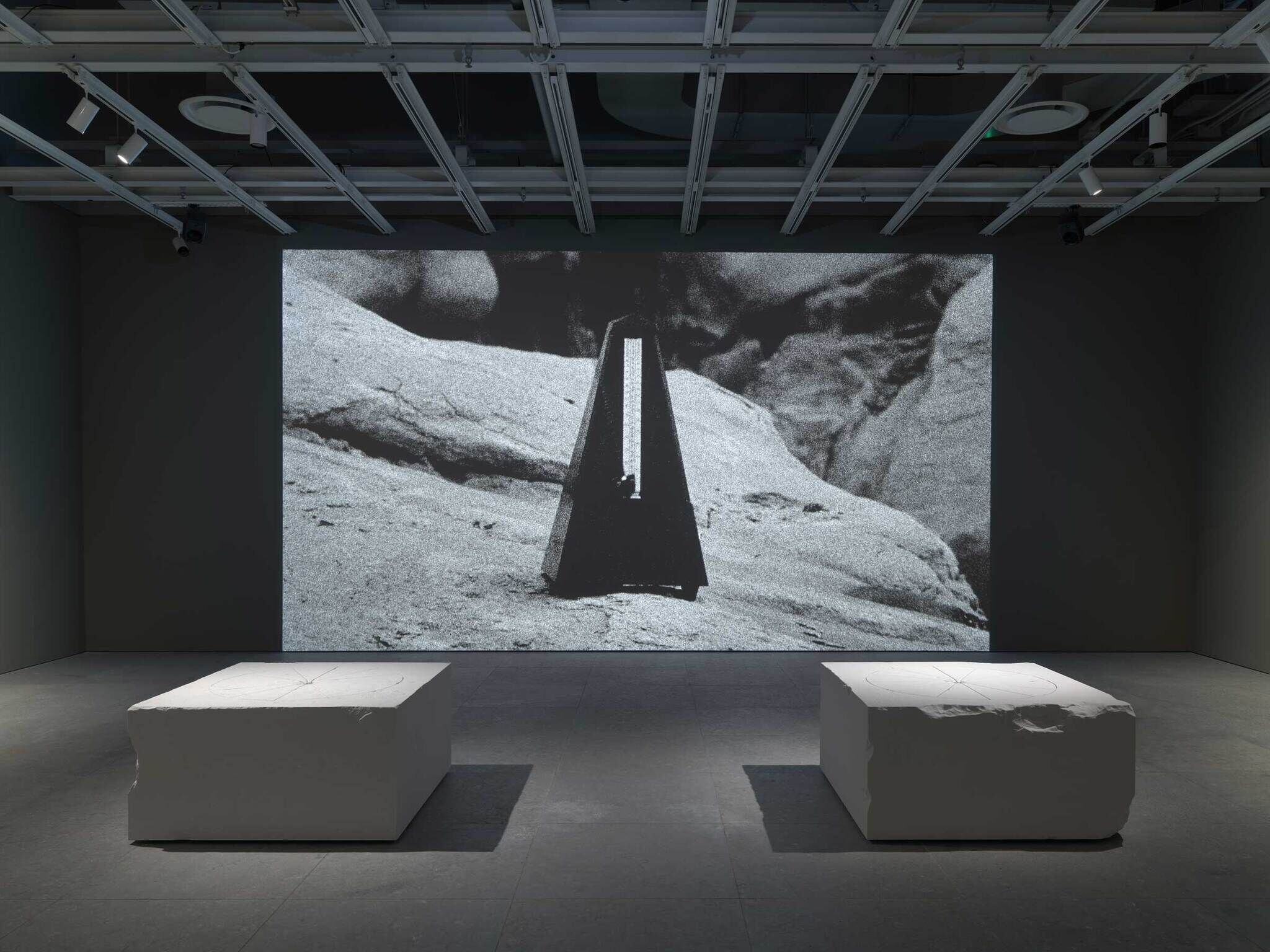

Here, there are black-and-white photographs and, filling one wall, a film projection that is also in gray tones. The film has a ticking clocks soundtrack. Two large stone blocks sit in the center of the space, and a gallery attendant is by the entrance, who I nod to after I adjust my mask.

There are four large photographs of desert landscapes and sometimes bodies, presented as pairs of two on adjoining walls. Their forms tell a little story, a body that goes beyond itself. First there are three people embracing like one shape on the ground with large rocks behind them, then a wide shot of a cracked and barren landscape that resembles beautiful folds of fat flesh. On the next wall is a naked person splayed out and masturbating in a field of small white flowers and, finally, a rotting animal skeleton on scorched ground, becoming earth. Everyone’s face is obscured except the dead animal’s. When I turn, I see the final picture, a much smaller photograph of clouds and am delighted.

I walk around again and look once more at the three bodies in Somnia. At first glance, I almost see two bodies. As I look more closely, all the limbs dance, and the embrace comes together. I see all three.

The photographs are very grand. In their emotional scale, they are big and embodied. Curious, I step back into the lobby to read the wall text. It tells me that the works are created with techniques from old survey photography, and that I am looking at landscapes from southern California and New Mexico, where Mark Armijo McKnight grew up. Glad to know this, I look again and decide the old techniques do not seem to survey, which is to document and dominate, but instead, as the artist uses them, they greet the landscapes from a place of spiritual respect.

Aware of this, I am struck again by the elegance of each image’s construction.

I notice that the film is starting from the beginning. The wall text says I can sit on the blocks, which are like sundials, but, for some reason, I still ask the gallery attendant before I finally sit comfortably and watch the film, a single shot. My knees hurt from getting to the museum and walking on so much pavement, and I am glad to rest.

For eleven minutes, the video pans out from a ticking metronome, close-up, to more metronomes placed across a weathered rock landscape, which I know are the Bisti Badlands/De-Na-Zin Wilderness from the wall text outside. As I sit, the sound crescendos with the appearance of metronomes and then eases until the shot is wide, the last metronome tocks, and I am left with the sound of wind on the sandstone and in the air.

The video texture and the physicality of the photographs is erotic and pleasing. The symptoms of my migraine ease. The sound goes ticktock, but in a lovely way that feels like I am taken by a slow wave in a bath of sound, not overwhelmed with clocks. The gallery is a contained space that is filled, gelatin silver, and, as I take the art in, it extends beyond me.

I am familiar with the word “decreation” from Anne Carson’s book of the same name. This comes from the French writer Simone Weil, “undoing the creature in us.” Decreation is probably the Anne Carson book I understand least, although I haven’t read all of them. But I do understand this particular undoing and how beautiful and gay it is. The drama of trying to be alive, the impossibility of it all. I stand and look again at the rotting corpse of the goat, which seems to move and curl in on itself, grimacing.

I’m undone, and glorious, a creature remains.

Seeing meaningful art is often an undoing. The world is expansive beyond us, infinitely more, and we are of it. Encountering this expansiveness makes me feel awed, humbled, and called to a greater accountability. I find this kind of encounter sometimes also in landscape, the woods behind my house, and this art seems to me to be all about landscape. It seems to be about how tragically beautiful we all are and trying to pay respect to the music that is already there.

Sometimes I go to see art, and I’m not undone. What a disappointment that is. A lot of the art that people make today gives you something to think about but doesn’t seem to have felt anything. The Decreation photographs I could think about all day and keep feeling, so I get out my little yellow notepad, and I make a list. Laura Aguilar. Shoog McDaniel. badlands. O’Keeffe. György Ligeti. antimatter. reverence. I am curious to read some history about these places. I think especially about the clouds, one larger round cloud on the right of the photograph and wisps of something smaller to the left, and how wrought with emotion form can be. The last show I remember being this beautiful was Wu Tsang’s magnificent installation of Beverly Glenn-Copeland at the Guggenheim, and I thought about that show for a long time after.

Another person (also wearing a mask) comes and then goes. I sit on a limestone block and watch the video of the metronomes again, which is very nice and feels good in my body. I turn on the block and look around.

After I leave, I go and take a nap. My migraine lingers, which is what I get for crossing a boycott line to sample a novelty flavor. Later, my husband and I go to see Beverly Glenn-Copeland perform in Red Hook. The eighty-one-year-old artist announces that he has dementia, and that this will be his last tour. He sings “We are ever new, we are eev-err new,” and I think of those clouds.