Teacher Guide:

Laura Owens

Nov 10, 2017

WELCOME TO THE WHITNEY!

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, Laura Owens, on view at the Museum through February 4, 2018. This mid-career survey exhibition features approximately sixty paintings by Owens from the mid-1990s to the present. The exhibition reveals how the artist’s early work sets the stage for exciting new paintings and installations.

This teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team

About the exhibition:

LAURA OWENS

For more than twenty years, Laura Owens has pioneered an irreverent and innovative approach to painting by challenging its conventions while remaining deeply committed to its visual and emotional possibilities. Owens (b. 1970) was raised in suburban Norwalk, Ohio, and pursued her graduate studies in Los Angeles, where she has lived since 1992. At that time, she recalls, her more theoretically minded professors and peers viewed painting with suspicion, but this skepticism freed her to experiment with the medium precisely by appearing not to take it too seriously. She brought cartoon doodling to rigorous abstraction, along with other traces of her self-described middlebrow upbringing, such as the pastel palettes and frothy surfaces of decorated cakes and kitschy greeting cards.

Over the ensuing years, she has sampled imagery omnivorously, from medieval tapestries to emojis—all translated to canvas via a dazzling array of techniques, including gutsy brushstrokes, digital rendering, needlework, screenprinting, and folksy collage. For Owens, this heterogeneity serves as a feminist challenge to ingrained art historical hierarchies and traditional notions of good taste. Why can’t an ambitious painting, she asks, be sentimental, pink, or funny, or full of a mother’s experiences, animals, and googly eyes? Her work draws us in to throw us off, awakening our minds to the act of perception.

Throughout her career, Owens has shown a keen interest in how paintings invent spatial worlds while existing physically in the real one that they—and we—inhabit. Her often witty canvases depict pictures within pictures, sometimes mirroring one another, and have expanded to fill whole walls or rooms, unfurling across multiple panels that can be reconfigured depending upon where they hang. This survey of Owens’s paintings from 1994 to the present elaborates on that impulse through a loosely chronological sequence of freestanding rooms designed to evoke the spaces or exhibitions for which certain works were originally made. Each gallery serves as a discrete portal into a past moment, while also joining a conversation with works installed around it that engage the Museum’s larger architectural frame. Like Owens’s work, the exhibition proposes a vibrant experience of varying moods, imaginative conjecture, and poetic play.

More information:

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. We have included some selected images from the exhibition, along with relevant information that you may want to use before or after your Museum visit. You can print out the images or project them in your classroom.

Pre-visit Objectives:

- Introduce students to the artist Laura Owens and works in the exhibition.

- Examine themes students may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how Owens has experimented with materials, space, and pushing the limits of what a painting might be.

Laura Owens

Untitled, 1997

In her first solo exhibitions, during the mid-1990s, Owens set out to challenge the traditional notion of a series, which is usually characterized by a unified narrative or variations on a single form or theme. By contrast, she often imagined groups of paintings that looked nothing alike but were connected through hidden dialogues that viewers could discover. Owens made this painting to hang in a small office at a London gallery where she had a show in 1997. It was inspired by a photograph she took looking down a sequence of galleries at the Art Institute of Chicago, with various artworks receding into space. She has remarked:

“I thought it would be funny to do a painting that covered the entire wall and was composed of many smaller paintings, adding more space to the office and also camouflaging the work’s size.”

The canvas features works Owens was thinking about at the time, including a Van Gogh portrait of a woman in a large bonnet (center right). The precise paint handling demonstrates her keen interest in various techniques, from light staining to dense relief, while the blank raw canvas on the easel alludes to the artist’s creative act.

Artist as Observer:

What is a painting?

a. Discuss what students think a painting is and what they expect a painting to be. How might artists use painting as a way to observe the world around them?

Laura Owens made Untitled, 1997 to hang in a small office at a London gallery where she had an exhibition in 1997. It was inspired by a photograph she took of a sequence of galleries at the Art Institute of Chicago, with artworks receding into space.

b. With your students explore how space is represented in this painting. How would they describe the spaces they see? Why might an artist choose to create a painting of a gallery spaces? Why do they think the artist included an easel and a blank canvas in the center right of the painting?

Younger students could use viewfinders and older students could use their phones to frame and explore different views of their classroom or along their school hallways. Where can students find interesting views and frames? Which views show depth? Ask each student to make a quick sketch of a classroom or hallway view that interests them. Display students’ sketches. Which views did they choose? Why? Compare student drawings to Owens’s painting. What do students notice? Ask them to observe spaces through doorways as they travel to school or wherever they go.

Laura Owens

Untitled, 2002

In this canvas Owens conjures a fairy-tale image of the natural world, inspired by late nineteenth-century French decorative landscape painting. A nocturnal owl looks out from its perch against a moonlit night sky, while the surrounding menagerie frolics in soft daylight. The creatures interact with one another in a rhythmic choreography of gestures and glances, further enlivened by inventive paint handling that ranges from thick daubs and pale washes to runny brushwork across the slick ground of the trees. The dreamy scene tests our capacity to take seriously an ambitious painting that recalls a child’s picture book or animated film. Playing off the aesthetic categories of Minimalism and Maximalism, Owens jokingly dubbed it Maxanimalism, “a maximum-animals-per-painting painting.”

Artist as Storyteller:

Maxanimalism

“It could be that the painting is not behaving the way it’s supposed to . . .” —Laura Owens, 2014 Biennial Catalogue, Whitney Museum of American Art, 355.

a. Ask students to look closely at Owens’s Untitled, 2002 painting. Owens jokingly referred to this painting as Maxanimalism, “a maximum-animals-per-painting painting.” Have them describe what they see. How many animals can they identify? What would they hear and/or smell if they were in this painting? Which animals are looking at or engaging with each other? What else can they find that is surprising or unexpected? What connections can students make between the different elements in this painting? What story would they tell about this scene?

b. Challenge students to find the playing cards in the painting. Ask students to talk with a partner or tell a short story about why the cards might be in this painting.

c. For older students: Owens has made both abstract and representational paintings. What might an artist be able to do differently in a representational work compared with an abstract work?

d. For older students: Why do students think Owens playfully created a painting with as many animals as she could put in it? How might this challenge expectations about what a “serious“ painting could be? How would students describe this painting? Make a list of the words they come up with. When you visit the Museum, bring their list of words and look for other works by Owens that students might apply those words to. Ask students to look for other things in Owens’s paintings that might seem cartoony, cute, or humorous. What can they find that pushes the limits of what they think a “serious” painting might be?

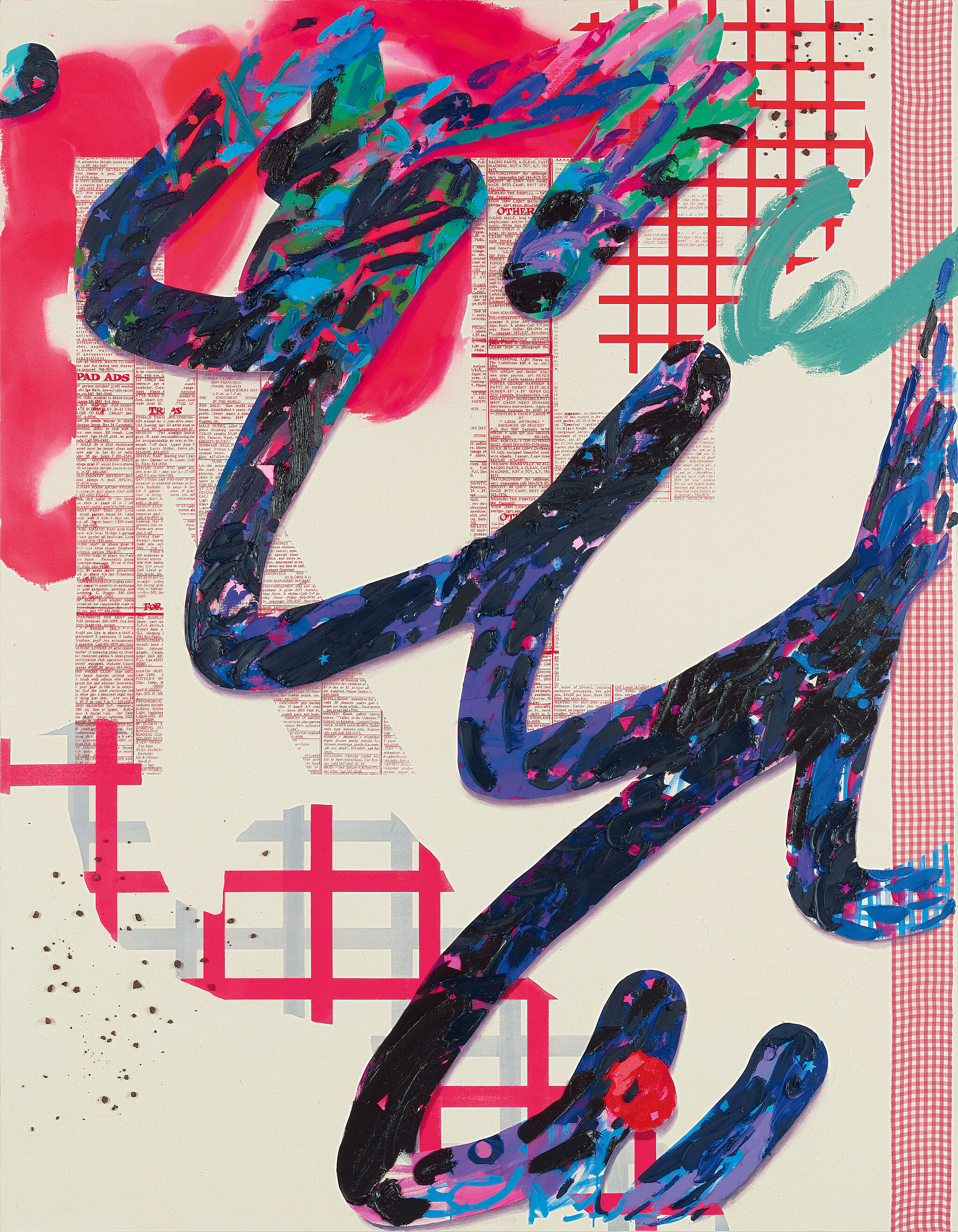

Laura Owens

Untitled, 2012

After nearly ten years focused on self-contained, largely figurative canvases, Owens turned her attention back toward abstraction and to multipanel paintings that tested the conventional relationship between part and whole—and between art and architecture. Owens further questioned what she called the “group dynamics” of paintings in her exuberant cycle of seven “Pavement Karaoke” canvases, a phrase borrowed from a sing-along party planned at her Los Angeles studio. The two words act as a linguistic armature spanning the backgrounds of six of the panels, atop which Owens layered gingham fabric, pumice stones, screenprints of 1960s classified ads from the Berkeley Barb, and crusty dollops of paint accentuated by drop shadows like those found on computer screens. Although the paintings developed as a suite, they can be shown individually. Each panel is simultaneously a fragment and a whole, concentrating our attention both within and beyond its edges.

Artist as Experimenter:

Markmaking

a. Ask students to look closely at Owens’s Untitled, 2012 painting . Have students make a list of words that describe the marks that Owens has made. Give younger students the list of words below and ask them to match the words with the marks.

- Curved

- Wavy

- Straight

- Blended

- Smudged

- Spotted

- Gridded

- Checkered

- Criss-crossing

- Overlapping

b. Ask younger students to lift up an imaginary paintbrush in their hand and “air paint” the gestures and marks they think Owens used to create this work.

c. In small groups, younger students could make collaborative collages with a variety of layered materials. For example, a material that is transparent, one that has an interesting texture, and one that has a color or pattern. Have students cut out shapes and experiment with different compositions and changing the order of their layered shapes. When they are happy with their composition, have students secure the different parts of their collages with gluesticks, tape, or stickers.

d. For older students: have students use their list of mark descriptions and pencil and paper to experiment with those marks. Display and discuss students’ drawings. How did they interpret Owens’s mark-making? What different marks of their own did they invent?

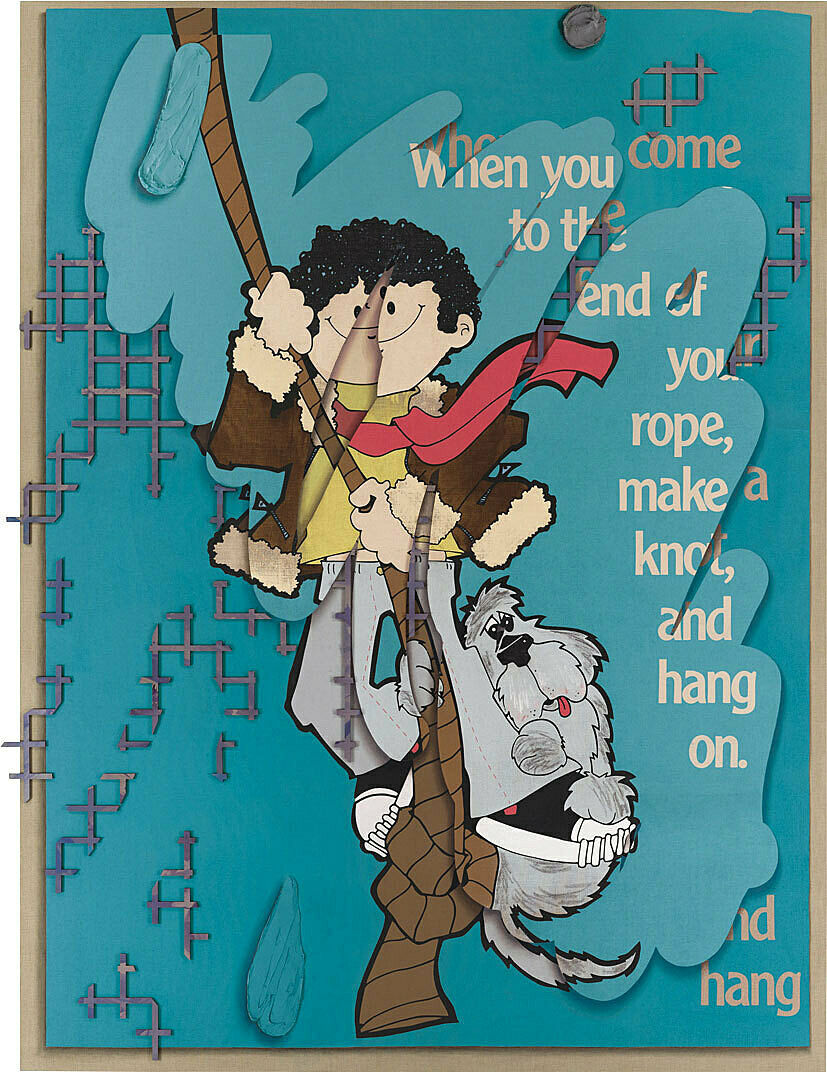

Laura Owens

Untitled, 2014

Owens has experimented with unconventional processes since the start of her career, but over the past five years she has pushed her paintings toward new levels of technical and material complexity. Collaborating with various specialists and assistants, she often develops a painting by working back and forth from computer to canvas. She may begin with a handmade sketch or collage and refine it on-screen before transferring the image to canvas through an array of techniques ranging from printing and projection to vinyl stencils cut by a plotter—methods that have increasingly allowed her to incorporate found pictures and text directly into her work. A painting progresses in stages as its imagery is fed back into the computer via digital photography and adjusted further, then output again in new silkscreens and templates, sometimes dozens for a single work. Owens pairs these layered procedures with an almost alchemical approach to materials, blending various paints and inks with unusual additives like fluorescent dyes and charcoal dust and occasionally attaching a sculptural appendage. The resulting works offer mesmerizing visual riddles confusing the printed and painted, machine- and handmade, invented and found, analog and digital. In this sense, they evoke the constantly shifting nature of our contemporary visual culture through images and surfaces that feel at once alien and familiar.

Artist as Experimenter:

Catchy Clichés

Each particular painting has a sort of grab bag of places it’s coming from, and those get kind of mixed and chopped up and moved around, and among those elements can be just something that happened on a hike or it can be a painting I saw in a museum or a drawing I made. —Laura Owens

a. Have students look at Owens’s Untitled, 2014. Where have they seen images like this before? What image would students create using the words in this painting? What are some other phrases that seem cliché, catchy, kitsch, cute, or corny? For example,“Home is where the heart is” or “All that glitters is not gold.”

Use this resource for other examples of clichés.

What image would students create for one of these catchy phrases? Ask students to divide into small groups. Have them find a cliché that interests the group, then brainstorm and draw an image along with the words of the cliché.

Post-Visit Activities

Post-visit Objectives:

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artists’ ideas through discussion, art-making, and writing activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask your students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class. Discuss the difference between seeing Owens’s paintings in person compared to seeing them reproduced in this guide. Talk about size, scale, space, and the impact of Owens’s work.

Artist as Experimenter:

Name it!

Laura Owens does not title her works because she says that she is no good at titles. Ask your students to brainstorm titles for Owens’s paintings in this guide. For inspiration, have them look at their lists and words that they created for pre-visit projects.

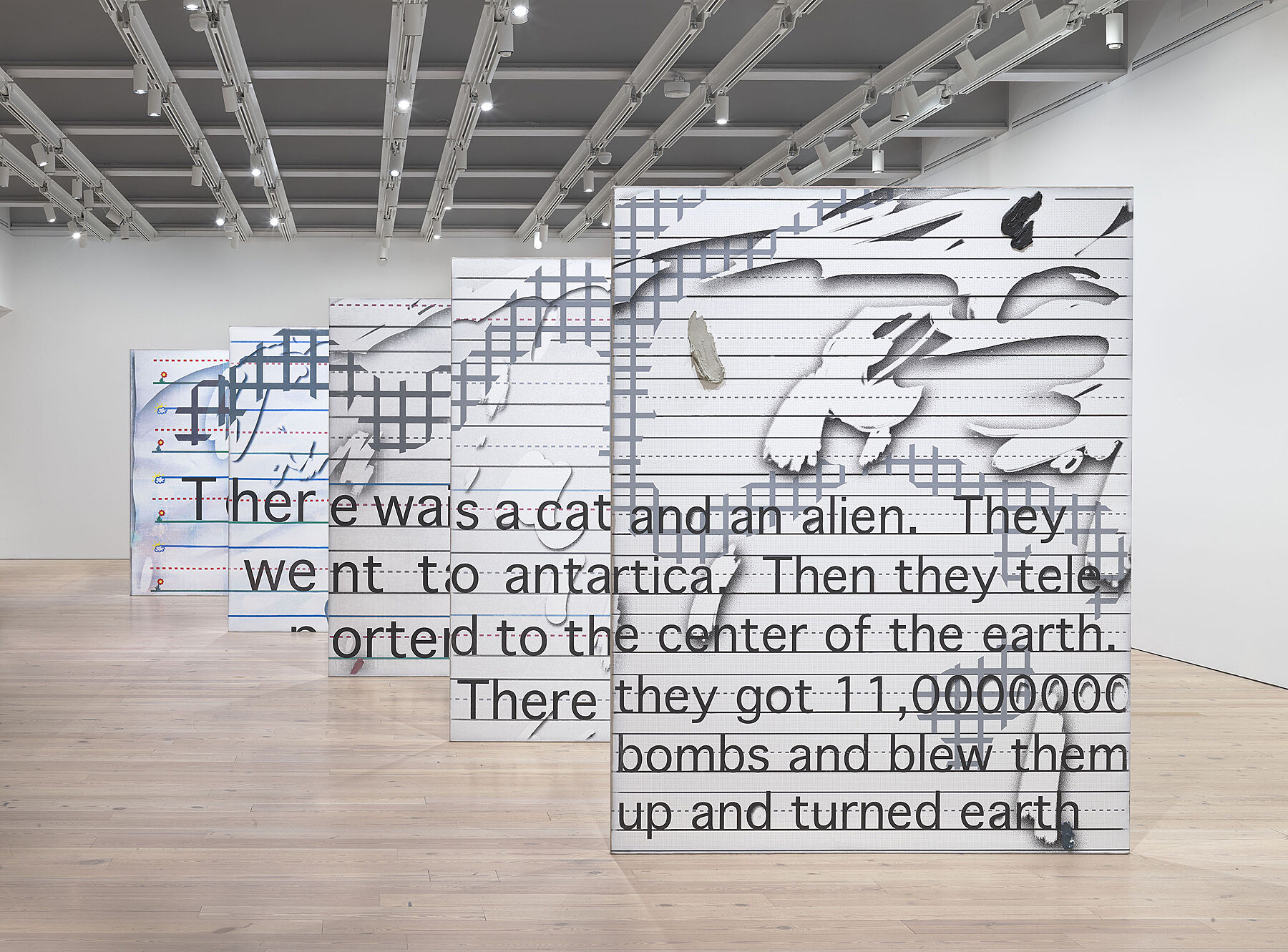

Laura Owens

Untitled, 2015

Owens’s Untitled installation from 2015 exemplifies her persistent exploration of the interplay between painting, architecture, and perception. Five freestanding canvases are anchored directly to the floor as elements of a single sculptural work that visitors are invited to circulate around and through. At first glance, the painted surfaces offer only fragments of drawings and text, but the panels cohere visually when observed from specific points at different ends of the gallery, encouraging viewers to discover their own perspectives on the work. From one vantage, the paintings reveal an excerpt of a fairy tale written by Owens’s then nine-year-old son, Henry Bryan, whose drawings of scented-marker flavors can be seen from the opposite direction. A complex amalgam of painting, printing, and sculpture, the images on the successive panels are rendered with increasing clarity as they recede from view, rather than blurring with distance as objects normally would. This perspectival play resonates with the fantastical quality of Bryan’s story, ingeniously conflating image and object, reading and looking, experience and imagination.

Artist as Experimenter:

Collect and Create

a. If your students saw Owens’s 2015 installation on Floor 8: ask them to describe what is experimental and/or surprising about this work. Show them the image of the installation and share information about this work. How is Owens experimenting with painting in space? In what ways might this experimentation challenge what painting can be? Why do students think Owens borrowed her son’s story to create this piece? Why might it be valuable to an artist to borrow images and words from another source?

b. Ask our students to “collect” marks and images from Owens’s work in this guide or use their sketches from the pre-visit projects in this guide. Have students combine the marks and images to create individual drawings or paintings. Ask students to work collaboratively to decide how they might hang or install their artworks in the classroom in a surprising or unexpected way.

Bibliography and links

/exhibitions/laura-owens

Laura Owens exhibition on whitney.org.

https://www.owenslaura.com/

Laura Owens’s website.

https://www.makers.com/laura-owens

Makers video featuring Laura Owens.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/30/the-radical-paintings-of-laura-owens

New Yorker article about Laura Owens and her work.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1s74fES8qLY

LA MOCA video about Laura Owens, 12 Paintings exhibition at 356 S. Mission Road, 2013.

http://x-traonline.org/article/still-li%EF%AC%81ng-conversation-with-laura-owens/

Stephen Berens and Jan Tumlir, "Still Lifing: Conversation with Laura Owens, 2013."

https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/2009-interview-with-laura-owens/1768

Whitehot Magazine interview with Laura Owens, 2009.

https://www.believermag.com/issues/200305/?read=interview_owens

Believer Magazine interview with Laura Owens, 2003.

/collection/works

The Whitney’s collection.

/education

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

/for-teachers

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Hakimah Abdul-Fatteh, Assistant to School and Educator Programs, Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs, and Kristin Roeder, Whitney Educator.

Education Programs are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, the Dalio Foundation, The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation, Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Barker Welfare Foundation, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the Whitney's Education Committee.

Endowment support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, The Paul & Karen Levy Family Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Steven Tisch, Lise and Michael Evans, Barry and Mimi Sternlicht, Laurie M. Tisch, and Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools are endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

Major support for Laura Owens is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Whitney’s National Committee.

Significant support is provided by Nancy and Steve Crown; Candy and Michael Barasch; The Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston; Mariel and Jack Cayre; Marcia Dunn and Jonathan Sobel; and Erin and Peter Friedland.

Generous support is provided by Fotene Demoulas and Tom Coté, Allison and Warren Kanders, and Ashley Leeds and Christopher Harland, and anonymous donors.

Additional support is provided by Rebecca and Martin Eisenberg, and Susan and Leonard Feinstein.

Generous endowment support is provided by Sueyun and Gene Locks, and Donna Perret Rosen and Benjamin M. Rosen.

Curatorial research and travel for this exhibition were funded by an endowment established by Rosina Lee Yue and Bert A. Lies, Jr., MD.