Teacher Guide:

Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist

Oct 3, 2015

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, on view at the Whitney from October 2, 2015 through January 17, 2016. Comprised of works spanning 1919 to 1972, the exhibition is the first full-scale survey of Archibald Motley’s paintings in two decades and an unprecedented opportunity to carefully examine his dynamic depictions of twentieth-century American life.

Dedicated to exploring the richness and diversity of African American culture, Motley focused on depicting contemporary African American life, which was unsual in the early years of the twentieth century. He is best known for his naturalistic portraits, stylized street scenes, and jazz cabarets that visually embody the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance.

Read a review of the exhibition in The New York Times.

When you and your students visit the exhibition, you will see a selection of paintings by Motley that chart the evolution of his style, his use of vibrant color, and his exploration of ideas over time. This guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offers suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts. These materials have been written for Elementary, Middle, or High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team at the Whitney

ARCHIBALD MOTLEY: JAZZ AGE MODERNIST

Why should the Negro painter, the Negro sculptor mimic that which the white Man is doing when he has such an enormous colossal field practically all his own: portraying his people historically, dramatically, hilariously, but honestly. And who know the Negro race, the Negro soul, the Negro heart, better than himself?

—Archibald J. Motley, Jr.

Archibald Motley’s life

Painter Archibald J. Motley Jr. created portraits and scenes that reflect the African American experience of his era. Although he was associated with the Harlem Renaissance, a creative flourishing of the literature, art, music, and culture of African Americans, he never lived in New York’s Harlem neighborhood nor did he associate with those artists. In fact, he did not feel that the visual arts were as important to the Harlem Renaissance as other art forms. Nevertheless, he is still best known for his portraits and paintings of urban street scenes and jazz cabarets, which visually embody the spirit of that movement. Dedicated to exploring the diversity and richness of black culture through naturalistic portraits, and later, stylized genre scenes of everyday life, Motley embraced drama, humor, and honesty.

Motley was born in New Orleans to parents who held some of the most prestigious jobs available to African Americans at the time. His mother was a school teacher; his father, a porter for Pullman railroad cars. Motley was of African American, Creole, and European descent. His light skin and middle-class status afforded him opportunities that were often out of reach for other African Americans in that period. Like many African Americans at the time, the Motleys migrated to the North in search of better economic opportunities and to escape the South’s rampant racism. Motley was two years old when he settled with his family in Englewood, a mostly white, middle-class suburb of Chicago, where he attended mostly white primary and middle schools.

Motley attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), a prestigious institution that was one of the first colleges to allow black students. There, he trained in formal, conventional painting techniques including traditional compositions and representational drawing methods. Motley thought that he ought to “abide by principles of true art, as our [white] brethren do.” Although mostly accepted by the other students, Motley nevertheless experienced some harassment. Despite the difficulties of paying his own way through school, Motley earned good grades and won several awards for his artwork.

At SAIC, he met other black artists, as well as artists whose works centered on the modern, urban American experience. These experiences led him to embark on a career that focused on depicting contemporary African American life, which was unusual at the time. Using the traditional techniques he had learned, he painted portraits that depict African Americans in a dignified way, rather than in the stereotypical or caricatured ways that white artists had often portrayed African Americans. Motley wanted to represent the American Negro honestly and sincerely. He said: “I feel that my work is peculiarly American; a sincere personal expression of the age and I hope a contribution to society.”

After graduation from SAIC in 1918, Motley had immediate success. He exhibited widely and won many awards, including a prestigious offer to study abroad in Paris, through a 1929 Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1933 he began teaching at Howard University and working for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (FAP) as part of a New Deal program to give work to unemployed artists during the Great Depression. After a courtship of fourteen years, Motley married his neighborhood friend Edith Granzo. Her family, of German descent, disowned her because of her interracial marriage. Archibald J. Motley III (Archie), Edith and Archibald Jr.’s only son, was born in 1933. Archie later recalled that the family rarely went out together because of constant racial prejudice. It was only in 1929–30, when Motley was living in Paris with Edith, that the couple was able to socialize more freely, since a more tolerant attitude prevailed there.

Motley came of age during a turbulent and exciting time in American history, and he witnessed developments such as rapid industrialization, the Great Depression, and World War II. He was probably most inspired by the Jazz Age and Harlem Renaissance, both of which peaked in the 1920s.

Although named for a neighborhood in New York City, the Harlem Renaissance extended to other cities such as Chicago and New Orleans. In Chicago, Motley documented African Americans at leisure in “Bronzeville” (a reference to the brown complexions of the people who dominated its streets and boulevards), a neighborhood in the South Side of Chicago where many African American families had settled. The area, about ninety percent black, had a thriving African American business community and music culture, especially that of jazz and blues. Motley studied Chicago’s African American community intently, painting its black elites as well as its recently arrived Southern migrants, unseemly slackers, and troublemakers. After a hard week of work, Motley observed African Americans as they danced, drank, and enjoyed the social entertainment offered in “Bronzeville,” a place where people of different races, economic circumstances, and social status could come together. As a light-skinned black man living in middle-class Englewood, he was both an insider and an outside observer of his fellow African Americans.

Between 1930 and 1949, Motley executed numerous paintings celebrating scenes of everyday life, including depictions of picnics, barbeques, parades, and urban nightlife. His works from this period reflect the cultural milieu: rhythmic figures, pulsating colors, and animated compositions all suggest the high energy of jazz. Motley used both natural and artificial light to give his figures an unusual intensity—and his vibrant colors became one of the most distinctive features of his work.

Portraits

Motley sought to improve race relations by dispelling stereotypes through his art, skillfully creating sensitive, nuanced portraits of African Americans. He also wanted to expose his fellow African Americans to the fine arts. He felt compelled to depict a mostly positive image of black businessmen, cultured women, workers, and family members who surrounded him. He wrote: “I sincerely hope that with the progress the Negro has made, he is deserving to be represented in his true perspective, with dignity, honesty, integrity, intelligence, and understanding.”

In many of his portraits, Motley captured his sitters’ poise and demeanor, conveying a sense of their achievement, in addition to creating a believable likeness. Motley hoped that if blacks could see themselves in art they would gain an appreciation for their own racial identity. And he hoped that if whites could see the beauty and accomplishments of African Americans, stereotypes and racism might be dispelled.

In one series, Motley depicted African American women with different shades of skin color. He titled his portraits of racially mixed women with the Creole classifications that specified the amount of Negro blood they supposedly had—“mulatto” (half), “quadroon” (one-quarter), and “octoroon” (one-eighth). This was an important distinction at the time because it determined social status and legal rights.

Motley’s portraits, although masterfully executed, may suggest that he had complex feelings about race. He sometimes referenced stereotypes that equated physical appearance with social status. The light-skinned octoroon woman is beautiful, but she remains nameless, known only by her racial designation. But, as in the portrait of his grandmother, he also portrayed African Americans as dignified and unique individuals at a time when it was uncommon to make African Americans the subject in a work of traditional fine art.

Genre Scenes

With his genre painting, Motley wanted to alter attitudes toward black culture. He wanted to “bring about better mutual understanding between the white and colored races.” He believed that in his work, blacks and whites would recognize themselves and their shared experiences as modern, urban Americans. According to scholar Amy Mooney, Motley often borrowed from the conventions of film, a popular medium most viewers would be familiar with, in order to create his scenes.

One might even say that, in his genre scenes, Motley used the techniques and methods of movie making to further social change. He employed cinematic techniques such as close-ups, panoramas, dramatic lighting, staging, elaborate costumes, and artifice all to dramatic effect. Through his inspiration from film, Motley created a unique, distinctive style; and one of the first series of paintings that depict contemporary black urban life in America. His urban scenes exalt black accomplishments, self-sufficiency, and independence from the white world. They also provide white people a rare opportunity to view this intimate world. Through his paintings, Motley presented black culture as modern, approachable, and concerned with the same universal conditions as other Americans. Figures dominate his work and command the audience’s attention; unlike the subservient figures of the past, they challenge the prevailing racism. In his genre scenes, figures are rarely shown realistically. He exaggerated facial features to create a cast of stock characters that he sometimes repurposed in other artworks.

Scholars have debated the reasons for why he chose to paint caricatures of African Americans when he was so sensitive to the individual in his portraits. Some speculate that he sought to make his figures familiar and accessible to his viewers. Or, perhaps he may have used these stock characters, with their inherent associations (the bumbling man, the “mammy” figure), as an easier way to communicate his narratives. Or he may have used them simply for comic relief. Through scenes he believed to be accessible, humorous, and engaging, Motley intended his art to deliver a message of the social progress his fellow African Americans had attained in America. His work gave viewers insight into the African American experience, his ultimate objective.

Whether painting masterfully executed, detailed portraits or caricatured genre scenes, Motley’s work provides a remarkable view of family, friends, neighbors, and fellow Chicagoans and Parisians during an important time in America’s history. Motley always sought recognition for his skill by viewers of all races. His paintings were not meant to be an objective account of black life in America; rather they were a subjective history seen through the influences, ideas, and imagination of Archibald J. Motley Jr., a talented artist of mixed racial heritage who lived in Jazz Age America.

Credits

This introduction to the artist and works in the exhibition is adapted from an Interactive Exhibition Guide for Teachers prepared by Veronica Alvarez, Michelle Brenner, and Holly Gillette, Los Angeles County Museum Education Department, 2014.

Works Cited

Powell, Richard J, ed. Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist. (Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC, 2014)

Mooney, Amy M. Representing Race: Disjunctures in the Work of Archibald J. Motley Jr. (Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 24, No 2, 1999)

Mooney, Amy M. Archibald J. Motley Jr. The David C. Driskell (Series of African American Art: Volume IV. (Pomegranate Publishing, San Francisco, 2004)

Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist is organized by the Nasher Museum at Duke University and curated by Professor Richard J. Powell. The installation at the Whitney Museum is overseen by Carter E. Foster, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawing.

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. You may want to introduce students to at least one or two works of art in the exhibition. See the Images and Related Information section of this guide for examples of works that may have particular relevance to your classroom.

Objectives:

- Introduce students to the work of Archibald Motley.

- Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how Motley engaged with cultural, social, and political issues in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s.

Artist as Observer

PORTRAITS

Mending Socks, 1924 is a portrait of Archibald Motley’s paternal grandmother, Emily Sims Motley. He surrounded his grandmother with objects that were important to her. Motley’s grandmother was born into slavery. This part of her life is included in the painting: the portrait of a white woman at the top left is Emma Sims Kittredge, the daughter of the slave owner and the mistress whom Motley’s grandmother served while she was a slave. Emily Sims Motley was freed at the end of the Civil War, about sixty years before this painting was made.

a. Grades K-12: Ask your students to take a close look at Mending Socks, 1924. Let your students know that the person in the painting is the artist’s grandmother. What do they notice about her body language? Her facial expression? What might she be thinking about? Ask students to explore and discuss the objects surrounding her. What can they tell about Motley’s grandmother from the clues that the artist provides?

b. Grades 6-12: Tell your students that Motley’s grandmother was a former slave, and the woman in the oval painting on the wall at the top left of this artwork is Emma Sims Kittredge, her mistress during that time. Have students compare the two portraits. How are they different? Discuss how Motley depicted this aspect of his grandmother’s life.

c. Grades K-12: Ask students to think about a grandparent or another adult in their family. If they made a portrait of this person, what would they include? What activity would they show their subject engaged in to tell the viewer about that person’s life? What objects would they include to let the viewer know who they are? Ask students to reflect on how they would represent this person and discuss their ideas with a partner.

Motley’s portraits of African Americans generally express great dignity, confidence, and composure. He wanted viewers to see their beauty and accomplishments, hoping this might dispel negative stereotypes and racism. Motley once said that he wanted to paint every African-American skin tone, from dark to light—showing the beauty of all. He titled this painting The Octoroon Girl. “Octoroon” is an out-of-date term for a person who is one-eighth African American, and usually had somewhat lighter skin.

d. Grades 6-12: Ask your students to compare and contrast The Octoroon Girl, 1925 with Mending Socks, 1924. What differences can students find? For example, differences in who the women in the paintings might be, their poses, gaze, body language, and clothing.

e. Grades 6-12: Ask your students to define the word stereotype and discuss how they feel when people label or stereotype them. Ask them to write about an occasion when they were stereotyped. Ask student volunteers to share their stories. How did they respond and deal with being stereotyped? What would they want the person who stereotyped them to know about them? What would they want that person to see and understand differently?

ARTIST AS STORYTELLER

Migration

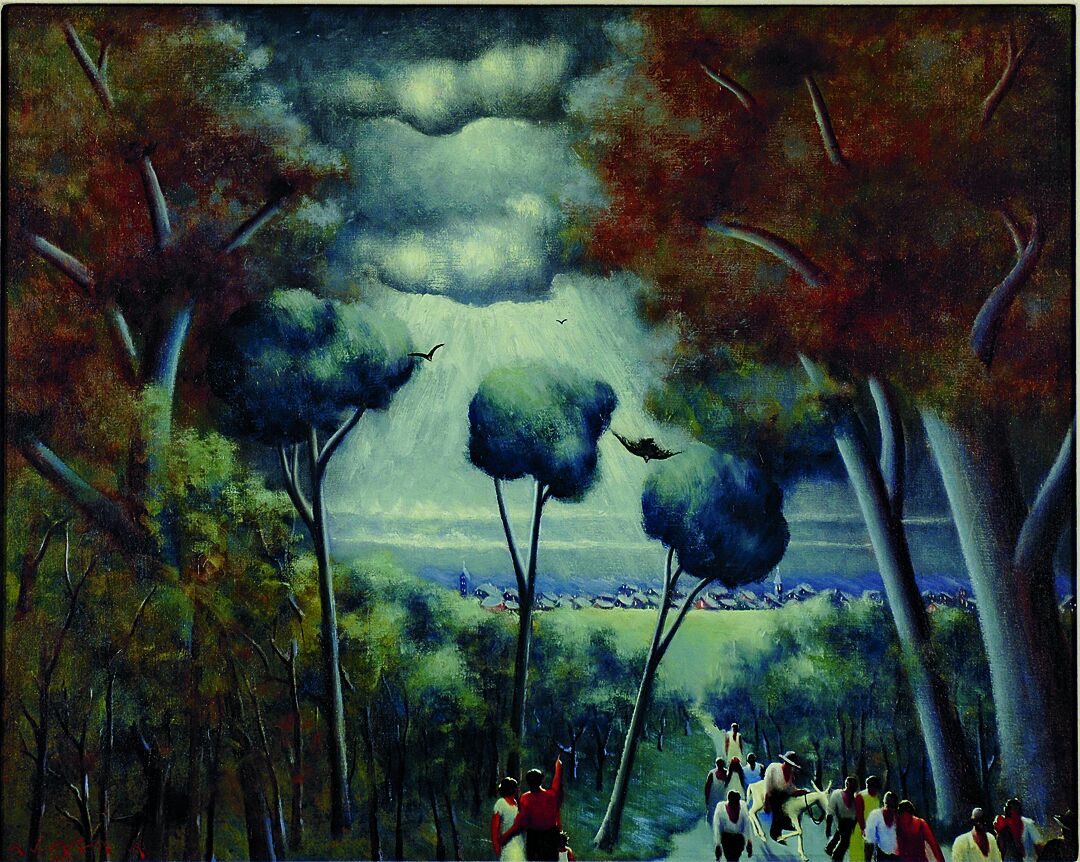

a. Grades K-12: Ask your students to look closely at Motley’s painting Town of Hope, 1927 and describe what they see. Ask students to notice the colors and discuss the mood of the painting. What do they notice about the way that Motley has depicted the town? Discuss the title of the painting. Does it seem like a town of hope to your students? Why or why not? Motley does not show any of the people’s faces. Why do students think he made that choice? What can they tell about the people by their body language?

b. Grades 6-12: Whether migrating or not, African Americans experienced racism in the North and the South. Ask your students to use the resources in the Bibliography and Links seciton fo this guide to research and discuss the Great Migration. What problems did African Americans encounter? How does students’ knowledge of the Great Migration change the way that they see this painting?

c. Grades 6-12: Ask students to discuss migration in the world today and related current events such as the refugee crisis in the Middle East and Europe. What do students think the refugees and migrants hope for? What problems and difficulties have they encountered? How do students think the world should address the Syrian refugee crisis? How might it be resolved?

Post-visit Activities

Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artist’s ideas through discussion and art-making activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Artist as Observer

STREET SCENES AND SOUNDS

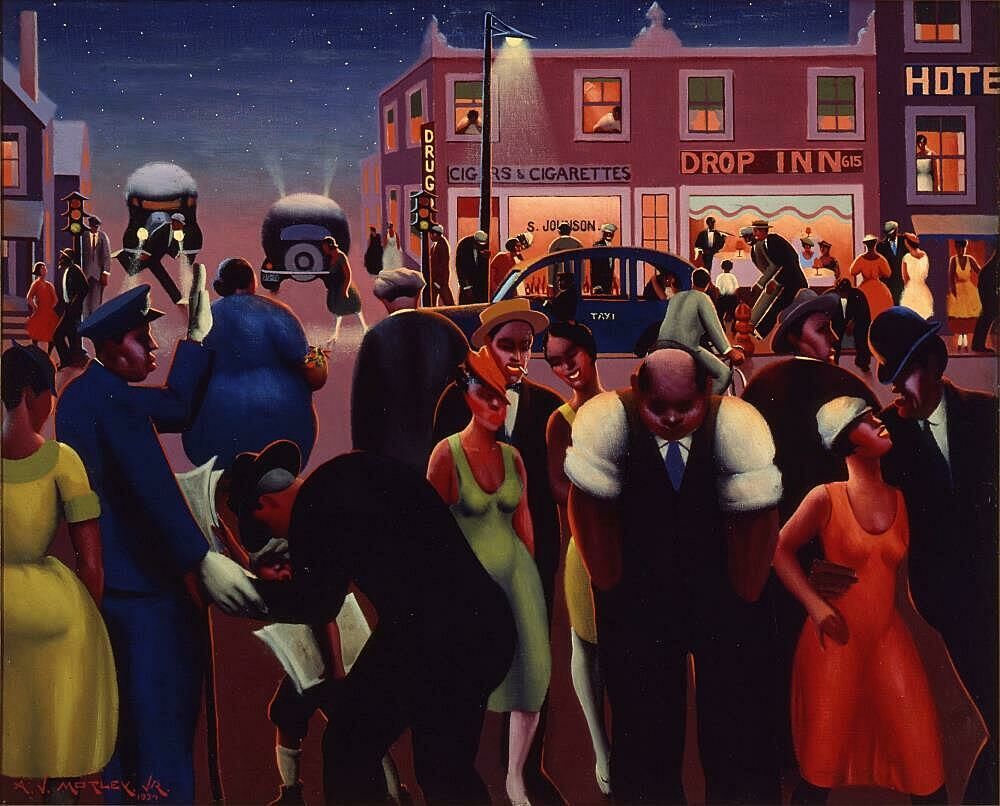

a. Grades K-12: Ask your students to review and discuss Black Belt, 1934. Ask them to explore how Motley exaggerates the color, lighting, and people’s features in the painting. What adjectives would they use to describe this scene?

b. Grades K-12: Ask students to imagine they are on this street. What sounds would they hear? What would it be like to be part of this crowd? If they were part of this scene, what would they be doing?

c. Grades 6-12: Your students could do the following project over the course of several days. What inspires students about their neighborhood? What are they proud of in their community? Ask students to choose a medium such as drawing, painting, photography, smartphone, video, or audio to capture the activity and culture on the streets of their neighborhood. View and discuss students’ work. What did they discover?

d. Grades 6-12: To extend this project, students could collage or edit their street scenes and sounds together to create a collective view of their neighborhoods and communities.

ARTIST AS CRITIC

RACE RELATIONS IN AMERICA

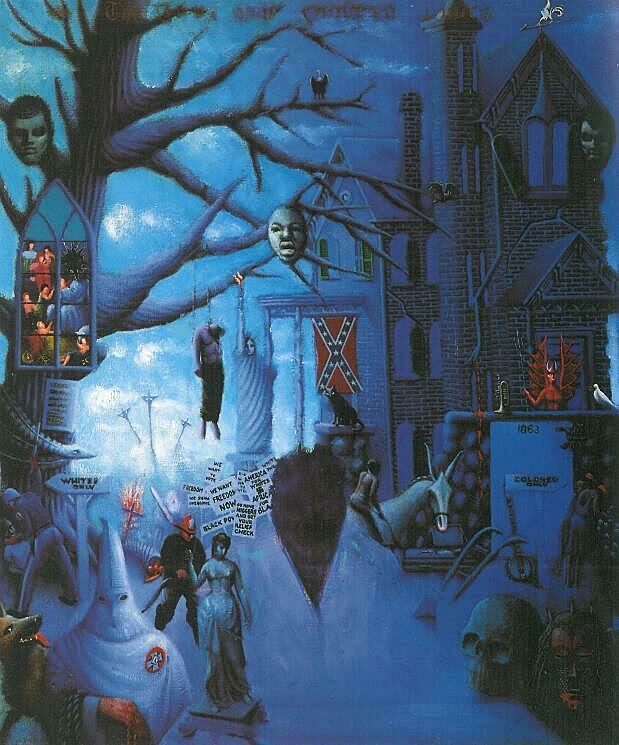

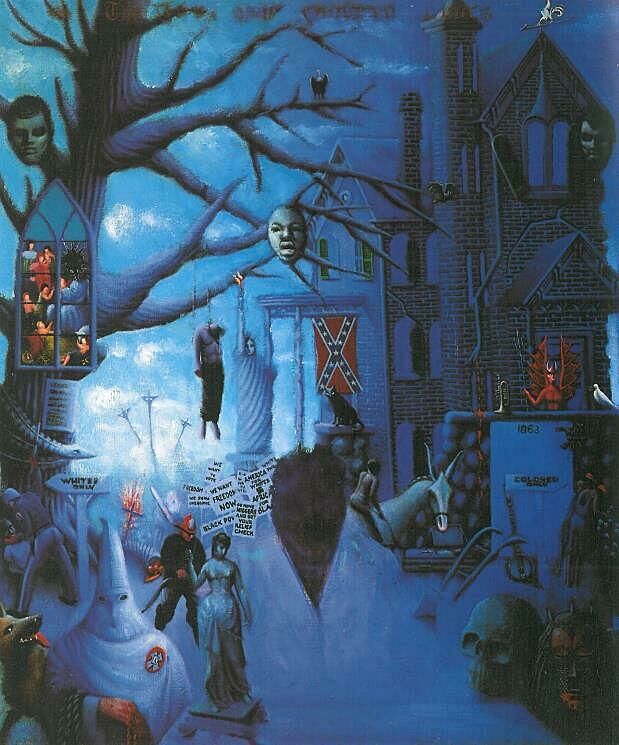

In The First One Hundred Years: He Amongst You Who is Without Sin Shall Cast the First Stone: Forgive Them Father For They Know Not What They Do, c.1963-72, Motley combined symbolism and allegory with real life occurences to depict the first 100 years after the Civil War. He worked on this painting from 1963-72, chronicling historical and political events as well as the decade that he was living in and experiencing during Civil Rights Movement. The events at that time included the Birmingham church bombings, and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy Jr.

a. Grades 9-12: Use the resources in the Bibliography and Links section of this guide to review the history of the Civil War through the Civil Rights movement. Ask your students to look closely at the painting. Explain that this painting is complex and may appear ambiguous. Ask them to discuss the images and symbols of racism that Motley included in the painting and their placement in the composition. For example, talk about why he chose to include images of Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and John F. Kennedy Jr. Why might he have juxtaposed a lynching and the Statue of Liberty side by side? Discuss how the confederate flag continues to provoke controversy in the United States today. What view of the first 100 years has Motley portrayed?

b. Grades 9-12: Students could do this project individually or in small groups. Ask students to research a social or political theme in current events over the past 20-30 years. For example, migration, immigration, war, civil rights, racism, gay rights, or feminism. Ask them to make a collage that chronicles this theme. Encourage students to use both literal and symbolic imagery. Ask students to use text that is related to their theme.

c. Grades 9-12: View and discuss students’ collages. Are there any common themes that students selected? Ask them to dig deeper. Discuss the current state of this issue. Where has progress been made? What obstacles have been overcome? What obstacles still exist? How do students think these obstacles might be addressed now and in the future?

Images and Related Information

MENDING SOCKS, 1924

Motley was extremely fond of his paternal grandmother Emily Motley, with whom he lived at his family’s Chicago residence in the 1910s and 1920s. With its peaceful domesticity, careful still-life arrangements, and patterned fabrics, this portrait of her references the interior genre scenes common in seventeenth-century Dutch painting. Motley had a sophisticated understanding of art history and effortlessly incorporated allusions to past styles. However, this work also nods to a more recent, American past and the complicated legacy of slavery: Emily Motley was, in fact, a former slave in the household of the woman represented in the upper left. Though he adhered to a traditional format for this painting, the artist depicted objects and people in a layered evocation and original combination of multiple pasts and histories.

THE OCTOROON GIRL, 1925

The Octoroon Girl—the title refers to an historic term for someone with one-eighth black ancestry-depicts a beautiful, fashionable, light-skinned woman. Motley, who was himself multiethnic, was very alert to the ways American society at large responded to darker or lighter skin tones. Contemporaneous novels such as Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929)—some recent editions of which have used this painting as a cover illustration—suggest the extent to which this was a common, potent concern, perhaps especially when questions surrounding skin, femininity, and sexuality arose simultaneously. But while the “tragic mulatto” was a well-established trope of literature and film, with mixed-race characters caught between their heritage and the temptation to try to “pass” for white, Motley depicted this one as modern, self-possessed, and confident.

TOWN OF HOPE, 1927

This painting’s title, Town of Hope, evokes an idealized version of small town optimism. But with its dark clouds and black crows, the painting’s overall mood is one of unease, trepidation, and upheaval. The streams of black migrants in the painting’s lower right suggest flight from the community on the horizon, implying that it has been less than welcoming. The painting seems to be more metaphorical than Motley’s urban scenes, alluding to the complex mix of hope, freedom, frustration, and loss that characterized many African Americans’ experiences of the Great Migration.

BLACK BELT, 1934

“I do not feel that there is anything in my work which is peculiar to Chicago,” Motley wrote in 1932, “but it is, indeed, a racial expression and one making use of great opportunities which have long been neglected in America.” Paintings such as Black Belt underscore Motley’s approach to picturing the modernist contours of black American experience after the Great Migration. He brought a wry, sometimes even jaded or cynical perspective to his subject matter, glorying in the spectacle. The electric lights irradiate the night scene with a surreal glow, and the figures are animated but somewhat anonymous. In his paintings of the urban scene, Motley often included an overweight man, elegantly dressed but often bearing cartoonish, stereotyped features. This man never engages fully in the actions depicted; rather he seems to serve as a surrogate for the real-life voyeurs of Bronzeville, whether white, black, or—perhaps especially—Motley himself.

THE FIRST ONE HUNDRED YEARS. . ., C.1963-72

Motley’s most overtly political painting is a modern allegory on the history of race relations in America. He began the canvas at the height of the civil rights movement and worked on it for nearly a decade. Its extraordinary, eerie blue tonality sets off symbolically loaded passages of red depicting, variously: the Confederate flag, blood, a burning cross, and the devil. The hanging body of a lynched black man is strikingly juxtaposed with the Statue of Liberty and the disembodied heads of three of the nation’s greatest champions of racial equality: John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Abraham Lincoln. In this radical artistic break from his life’s work, Motley sums up both personal history and national tragedy.

Bibliography and links

Powell, Richard J. Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist. North Carolina: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, distributed by Duke University Press, 2014.

Information about the exhibition.

http://nasher.duke.edu/motley/

Nasher Museum at Duke University, Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, images, information, timeline, audio guide, and documentary video.

http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-archibald-motley-11466

Archives of American Art oral history interview with Archibald Motley, 1978.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

The Great Migration

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_events_migration.html

PBS information about the Great Migration.

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african/afam011.html

Library of Congress information about Chicago as a destination of the Great Migration.

Syrian refugee crisis

An overview of the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East..

Civil War to Civil Rights

http://www.nps.gov/civilwar/civil-war-to-civil-rights.htm

An overview of the struggle against racism and discrimination from the Civil War to the Civil Rights movement.

Resources for the history of the Civil War through the Civil Rights movement.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; Heather Maxson, Manager of School, Youth, and Family Programs; and Pauline Noyes, Coordinator of School and Educator Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, Inc; The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation; Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody; Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo and The Dorothea L. Leonhardt Foundation, Inc.; the Barker Welfare Foundation; Con Edison; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Generous endowment support for education programs is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch, Steve Tisch, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, and Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick.

Free Guided Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools endowed by the Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

The Whitney’s Education Department is the recipient of a National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist is organized by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

This exhibition is made possible by the Terra Foundation for American Art; the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor; and the Henry Luce Foundation.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Additional support for the Whitney’s presentation of this exhibition is provided by the Viniar Family Foundation and an endowment established by Donna Perret Rosen and Benjamin M. Rosen.