About the Art and Artists: Hammons and Matta Clark

About David Hammons's Day's End

Before the Whitney opened to the public on Gansevoort Street in May 2015, David Hammons was invited to tour the Museum site with the Whitney’s Alice Pratt Brown Director, Adam D. Weinberg. On their tour, Weinberg pointed out the view across the highway to the location of the now-demolished Pier 52, where artist Gordon Matta-Clark created his iconic art intervention, Day's End, in 1975. Hammons has long admired Gordon Matta-Clark’s work and his ability to extract beauty and create poetic experiences in unlikely places, such as Pier 52. A few days later, Weinberg received a drawing from Hammons for a public artwork that the artist simply called a “monument to Gordon Matta-Clark.” This drawing formed the basis for the installation on view today.

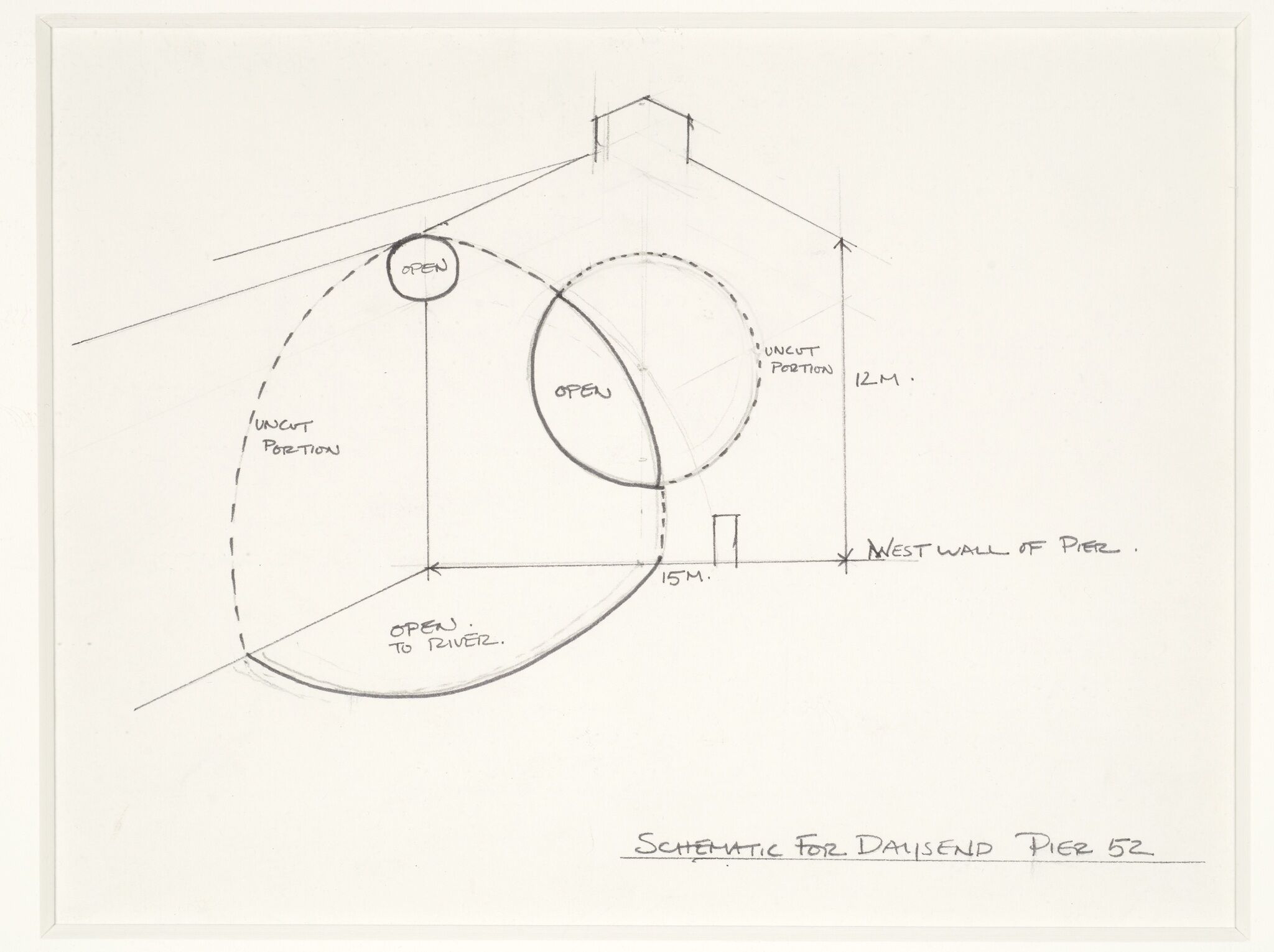

David Hammons and Gordon Matta-Clark both began their artworks with a sketch. Matta-Clark and his assistants cut five openings into the floor and walls of the empty, run-down Pier 52 shed that occupied the site in the 1970s.

Hammons’s Day’s End is positioned at the precise historic location of its namesake, outlining the dimensions of the former pier shed where Matta-Clark created a “temple to sun and water,” filled with undulating light—especially at sunset, or “day’s end.” Hammons began the new work as an homage to Matta-Clark. It is also a tribute to the history of the neighborhood, the waterfront, and its ever-changing relationship to New York City.

Hammons’s sculpture follows the outlines, dimensions, and location of the Pier 52 shed that occupied the site in the 1970s. Affixed to the shore on the south edge of Gansevoort Peninsula, the structure extends over the water, employing the thinnest possible support system. Day’s End is made of stainless steel tubes, connected together edge to edge to form three-dimensional drawing in space. The steel structure rests on twelve steel and concrete pilings. The structure has five columns on the shore line and seven columns in the Hudson River bed. It is 52 feet tall at its peak and 325 feet long.

Hammons's work seems to shimmer and almost disappear, changing with the light of day and atmospheric conditions. It also carries echoes of the history of New York’s waterfront—from the heyday of its shipping industry to the reclaimed piers that became a gathering place for the gay community.

About the Artist David Hammons, b. 1943

Born in Springfield, Illinois, David Hammons moved to Los Angeles in 1962, studying advertising at the Los Angeles Trade Technical College and then fine arts at Chouinard Art Institute (1966–68) and the Otis Art Institute (1968–72). At Otis Art Institute, Hammons trained with draughtsman and printmaker Charles White, a Black artist who had been committed to socially oriented art since the 1930s. His example was especially important to Hammons, who sought to connect his work to Black Power movements and the Black cultural nationalism of the 1960s. Hammons began making prints himself, many of which altered the American flag from red, white, and blue to the red, black, and green of the Pan-African flag. He also began making body prints, using his figure as the printing plate: he would smear his body, clothes, and hair with grease, press himself against a board, and then dust the resulting mark with pigment. He became, as he put it, “both the creator of the object and the object of meaning.”

After he moved to New York in 1974, Hammons became interested in artist Marcel Duchamp and his art became increasingly conceptual. In the mid-1970s, he began his metaphorical “spade” series, examining a derogatory term for African Americans that he claimed never to have understood. The works in the series often featured discarded shovels (literal spades), initiating a practice of using found objects that he subsequently expanded to include chicken bones, bottle caps, and paper bags. Hammons also began making sculptures and installations from human hair, which he collected from Black barbershops around the country. In one of his best-known performances, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983, he went to Manhattan’s East Village—the heart of the new gallery scene at the time—and stood on the sidewalk selling snowballs, implicitly questioning the value of the art.

Hammons has also made public works in urban settings. In Higher Goals, 1986, created for Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza Park, he and a group of locals installed five 20–30-foot-high telephone poles, topped them with basketball hoops, and covered the installations with thousands of bottle caps in configurations that suggested snakeskin, Islamic design, or African textiles. Hammons’s work also includes a series of paintings in which areas of the canvases are partially concealed by found material such as tarpaulins, towels, and garbage bags.

Gordon Matta-Clark Day's End, 1975

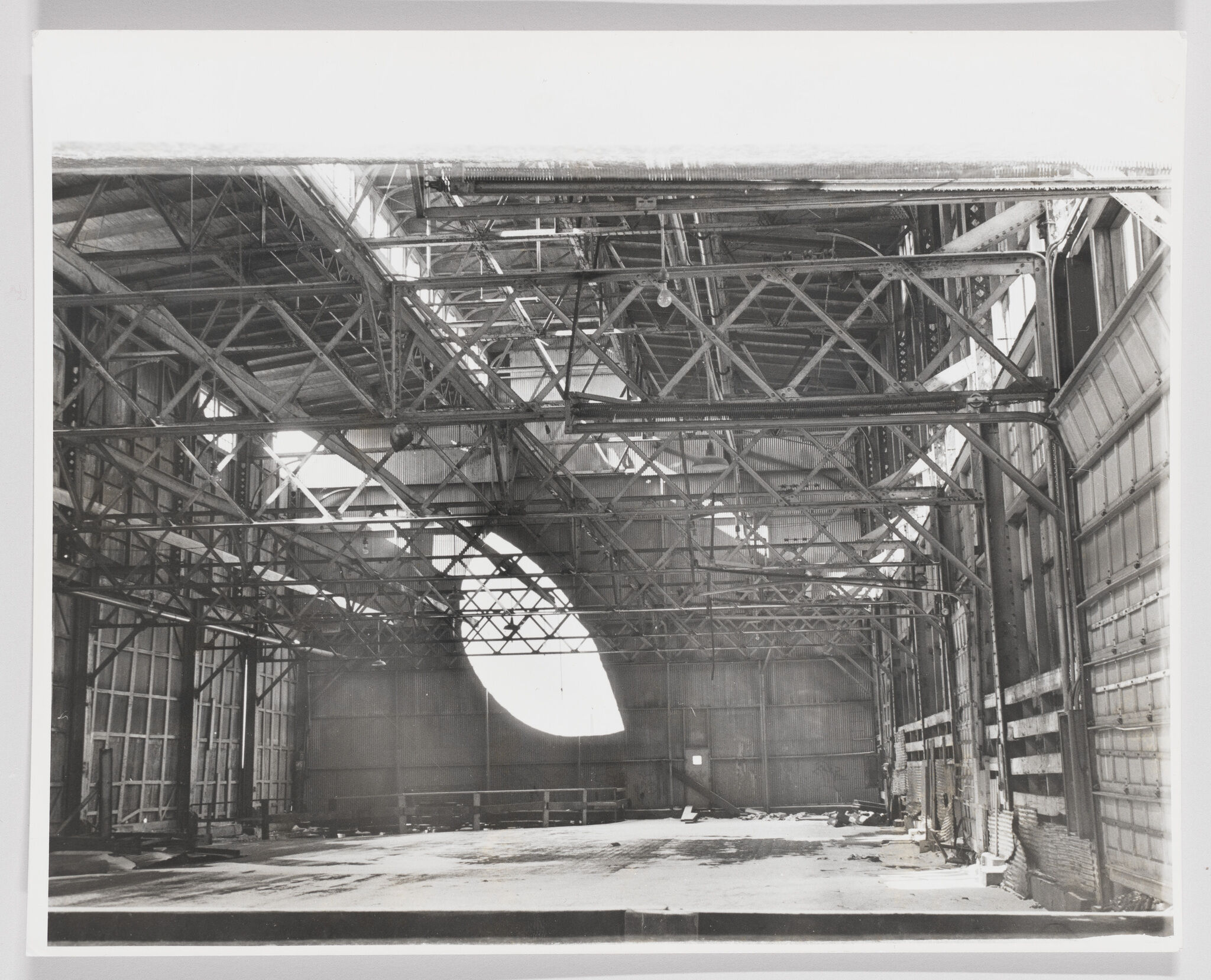

Gordon Matta-Clark’s project was created in the summer of 1975, when he illegally entered an abandoned industrial shed formerly used by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on Pier 52, near Gansevoort Street. His intent was to remove pieces of the building, opening the cavernous shed structure to both the river and the play of light of the sun and moon. He noted, “The project encompasses two areas of the pier; the first is a set of cuts through the roof, metal walls, and thick wood floor opening a 10-foot-wide channel and ‘river-door’ across the middle of the pier; the second treats the west end where major arches are cut in the wharf surface and walls working together to form a spherical quadrant.”

Matta-Clark and his assistants spent three months working at Pier 52. They created gaps in the floor revealing the Hudson River below, which mirrored long cuts in the roof, and carved out a half moon hole from the corrugated iron in the wall facing New Jersey. When complete, the artwork was intended to be an ever-changing play of light and water on the industrial space. A warrant for Matta Clark’s arrest was issued when the police realized what had happened. The shed was quickly impounded and then demolished around 1979.

Additional Resources

Whitney Museum: Information about the David Hammons, Day’s End project.

Hammer Museum: David Hammons biography. A concise summary of important moments in Hammons’s artistic career. Also provides a selected bibliography and links to articles.

CCA Wattis Institute: Essay on David Hammons by Anthony Huberman.

Public Delivery: Information about David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983.

Guggenheim Museum: Biography on Gordon Matta-Clark.

Hyperallergic: Feature on Gordon Matta-Clark.

Brooklyn Rail: Article about Gordon Matta-Clark.

Gothamist: Shelley Seccombe’s photographs of sunbathing on the West Side piers.

Artforum: Article about Alvin Baltrop and his pier photographs.

The Guardian: Photographs of the piers by Alvin Baltrop.

Curbed: Guide to New York City’s public art.

NYC Parks: Guide to public art in New York City parks.