The Collection in Context: Docent Training Course

Nov 18, 2014

In spring 2015, the Whitney will open its new building with an inaugural exhibition that will be the widest ranging presentation to date of its collection of twentieth- and twenty-first-century American art. The exhibition will fill over 60,000 square feet of indoor galleries and outdoor terrace spaces, offering new perspectives and expanded definitions of art in the United States since 1900 and celebrating the Whitney’s new home in the Meatpacking District. In preparation for the opening, Education is expanding our docent teaching corp and offering an art history course for current docents and docent trainees at Avenues: The World School in Chelsea. The fifteen-session course began on October 27, 2014 and runs through March 30,, 2015.

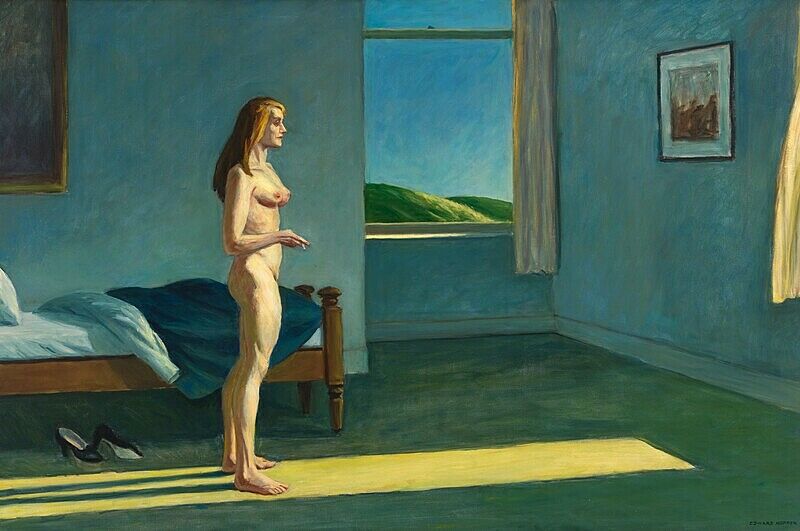

The first of five instructors for the course is Sasha Nicholas, an independent curator and art historian who is currently a doctoral student in art history at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Formerly an assistant curator at the Whitney, Nicholas served as co-curator of Breaking Ground: The Whitney's Founding Collection (2011) and Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time (2010-11).

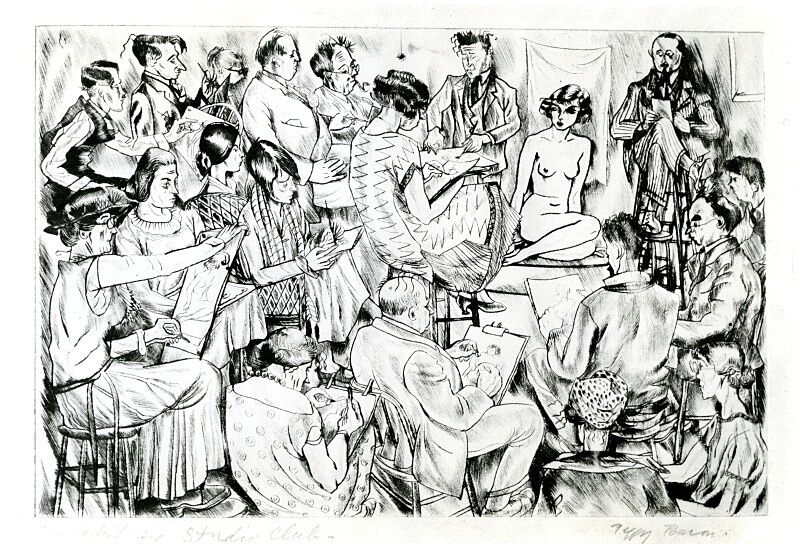

At the first session of the course, Nicholas introduced the themes of modern American art and the Whitney’s collection. She offered a history of the Whitney and the forces that shaped the Museum’s identity and its beginnings as the Whitney Studio Club, the birth of the American modern art museum, the break with the academy at the turn of the twentieth century and artists’ explorations of new directions and styles that conveyed the complexities of modern life. She also positioned the Museum and its collection in relation to emergent forms of realist and abstract art in the past 100 years that have defined and expressed the American experience.

To explore the tensions between abstraction and figuration during the twentieth century, Nicholas compared Edward Hopper’s iconic Early Sunday Morning (1931) with an abstract painting by Mark Rothko. She explained that Hopper straddles the polarities of realism & abstraction because even though he painted from reality, his paintings reveal the quality of an inner vision: “He’s not just painting what he sees, he is always distilling, reducing, abstracting from reality, even though the paintings don’t literally look abstract.”

Referring to a statement by the artist’s friend, writer and critic Brian O’Doherty on the subject of Hopper’s painting, Early Sunday Morning, Nicholas said: “On first glance, it’s just an ordinary building, but you spend time with this painting and those gradations of every window— the subtleties of light & form—every window is articulated in a different way, every window becomes like its own Rothko. Just as Rothko was making paintings about how light works and how we feel in relationship to it, so too was Hopper.”

Nicholas emphasized the importance of looking past things that seem obviously different and thinking about what might connect them. She referenced Hopper’s spare, austere exploration of space: how light hits a wall or rakes against a floor, inviting us to consider his interest in underlying structure and geometry, despite the representational content of his work.

She suggested that Hopper’s late paintings could be seen as a precursor to the work of an artist like Donald Judd. For example, his own exploration of light on geometric forms and his approach to bringing the viewer into a relationship with an object in three-dimensional space. Nicholas urged the Docents to keep these ideas in mind throughout the course, adding that it is helpful to categorize and classify art for museum visitors to understand movements and styles, but at same time, what makes art history so exciting is to use one’s eyes to probe beyond traditional boundaries and think about what seemingly disparate artists have in common.

Finally, Nicholas said that the Whitney’s commitment to a diverse range of artists and styles—values promoted from the outset by its founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and first director Juliana Force—puts the Museum in a unique position to tell stories that challenge traditional narratives, especially the prevailing notion that abstraction is the only modern language, while realist art is retrograde and anti-modern. Throughout its history, the Whitney has maintained a flexibility that may have initially appeared provincial, but has proven prescient and advantageous in today’s pluralist age of artistic production.

By Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources