Toyin Ojih Odutola:

To Wander Determined

Toyin Ojih Odutola:

By Her Design

To Wander Determined presents the private collections of two aristocratic families: the UmuEze Amara, one of the oldest noble clans of Nigeria, and the Obafemi, a minor aristocratic house whose prominence stems from their work as traders and ambassadors for various governances. The works presented here are entrusted to the current Marquess of UmuEze Amara, TMH Jideofor Emeka, and his husband, Lord Temitope Omodele from the House of Obafemi. Gathered from holdings at joint family seats in Amara Palace (Onitsha), Uzoma Hall (Port Harcourt), Udoka House (Lagos), and the Obafemi Family Vineyards (Ota), the selections on view are the result of a curated connoisseurship spanning nearly two hundred years. These collections are rarely shown outside the country.

To Wander Determined highlights works from Lord Omodele’s family and their travels as well as works loaned from the UmuEze Amara Collection. In partnership with the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, their lordships hope to expand upon their respective family legacies and engage visitors in an intimate experience of life between these two prestigious Nigerian houses.

Toyin Ojih Odutola

Deputy Private Secretary

Udoka House

Lagos

Toyin Ojih Odutola—draftswoman, writer, keen observer, creator of worlds—was born in Ife, Nigeria, in 1985. An exemplar of what she has described as the “wandering immigrant” tradition, she has been itinerant, a determined wanderer, in her locations and interests for much of her life. Points in her constellation include: Ife; Berkeley (and, much later, San Francisco); Huntsville, Alabama; and New York. Some other points to consider: Lucian Freud’s Reflection (Self-Portrait) (1985; private collection), and specifically “how the skin narrates the work and how it is the basis of the work . . . a thickly-laid, sculptural bounty of brushstrokes as flesh”;Toyin Ojih Odutola, “G is for Geography,” Alphabet: A Selected Index of Anecdotes and Drawings (blurb, 2012), n.p. Ukiyo-e and manga, and the many ways in which stories and space have been rendered across cultures and time; systems for heredity succession in the United Kingdom, Igboland, and other monarchies; fictional narratives (particularly fan fiction) and, more broadly, the uses of visual storytelling; wealth and social status (who has them, who doesn’t, and why—and, what good are they?); and the intimate power of both the artist’s hand and the human form in all its plenitude and diversity. In To Wander Determined, Ojih Odutola presents an interconnected series of sensuous and enigmatic drawings. Reinterpreting the traditions of portraiture, she pushes the genre beyond its roots into the realm of the psychological, the speculative, and the seemingly impossible.As she says of her subjects and settings, “What time are they in? Are they in the 1980s or in the 1920s? Because this is a fictional world, there’s a lot of freedom. I can place them anywhere because, yes, it doesn’t exist, but it could.” Unpublished audio interview with the artist.

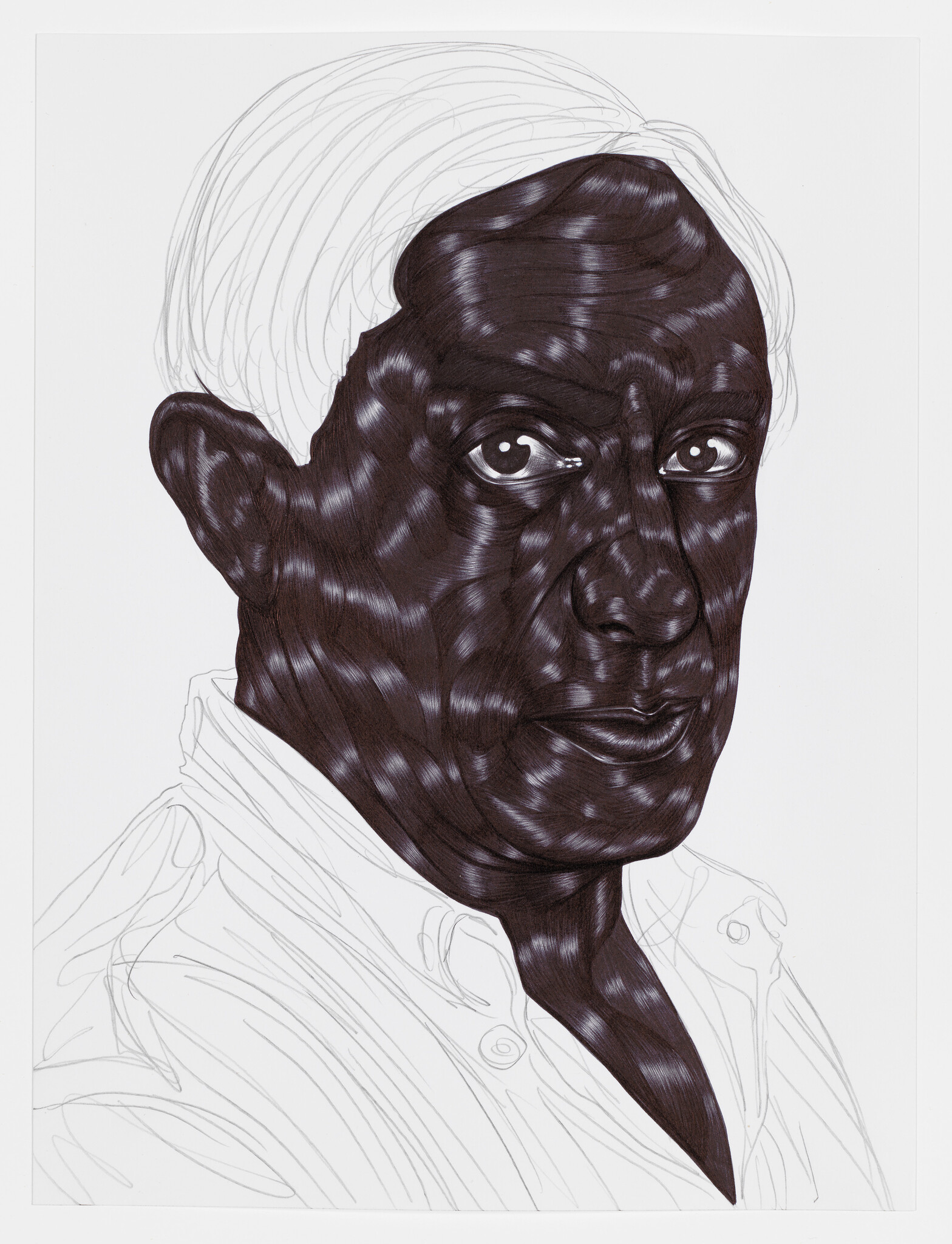

Initially known for her adherence to ballpoint pen and a generally monochromatic palette, here Ojih Odutola employs colorful chalk pastel and charcoal, constructing her figures through intricately applied layers of shading and sinuous line, interwoven to form labyrinthine patterns of rich tonal gradation. She began working in this distinctive style in the early 2000s, while an undergraduate at the University of Alabama, Huntsville, and continued to refine it during graduate study at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco. In this earlier period she focused primarily on the body, using meticulously layered marks to build up a surface that might approach the luminosity of skin—black skin, in particular. In more recent drawings, such as those in To Wander Determined, she has extended her focus to include landscape, architecture, domestic interiors, and materials ranging from wood to glass to fabric. However, her mark-making technique remains the foundation of her unique visual language, regardless of what she depicts. An encyclopedic and expansive thinker, she has also made travel—both as metaphor and as literal activity—an important theme in her practice. The idea of transporting or transforming the self—a process critical to artistic development—emerges continuously and manifests itself variously in her work. For example, she has described her depiction of skin in terms of transmutation, as a world unto itself that can be traversed and explored. “When I draw the skin of my subjects, I really want people to travel throughout them,” she says. “The surface isn’t something I trifle with. In the making of the work, skin is the geography I travel in order to discover each individual and his/her story. With every line I mark up, I map out the territory of their realities.”Ojih Odutola, “G is for Geography,” n.p.

The artist’s latest body of work centers on the private lives of two fictional Nigerian families joined by marriage: the aristocratic UmuEze Amara Clan and the nomadic House of Obafemi. The majority of the works included in To Wander Determined depict members of the latter family, the House of Obafemi, though members of the UmeEze Amara Clan do appear.Ojih Odutola explored the life of the UmeEze Amara Clan in an earlier body of work, exhibited as A Matter of Fact at the Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco, October 26, 2016–April 2, 2017. In contrast to her earlier works, characterized by cropped and decontextualized bodies floating in the open space of the page, these drawings portray figures in luxurious and fully fleshed-out environs. They are situated within a broader, unfolding narrative—a kind of modern-day odyssey that gradually reveals itself through fragmented moments, restless and contemplative glances, and a series of lightly veiled visual clues. The two families’ histories and social standing, as well as the purported provenance of the drawings, are disclosed through a letter (reproduced above) explaining that the works on view are part of a larger collection of commissioned portraits. Without providing specifics, the text indicates that both families are descended from prominent Nigerian lineages. While the letter claims to be a factual record of whom and what we are looking at, as viewers we are ultimately left with little clarifying detail. When were these portraits made? From what time period are the depicted figures? Who are the various family members, and what are their relationships to one another? Do the same people appear in multiple portraits, and if so, are they shown at the same age each time? Details can be gleaned from the works’ poetic titles, though even here we are left with more questions than answers. Furthering the conceit around her narrative while simultaneously removing herself as the artist, Ojih Odutola playfully signs the letter “Deputy Private Secretary, Udoka House, Lagos.” The sense of mystery around the work is heightened by this unexpected act of artistic de-attribution, and the insertion of the artist—or at least someone with the same name as the artist—into a narrative presumed wholly fictional.

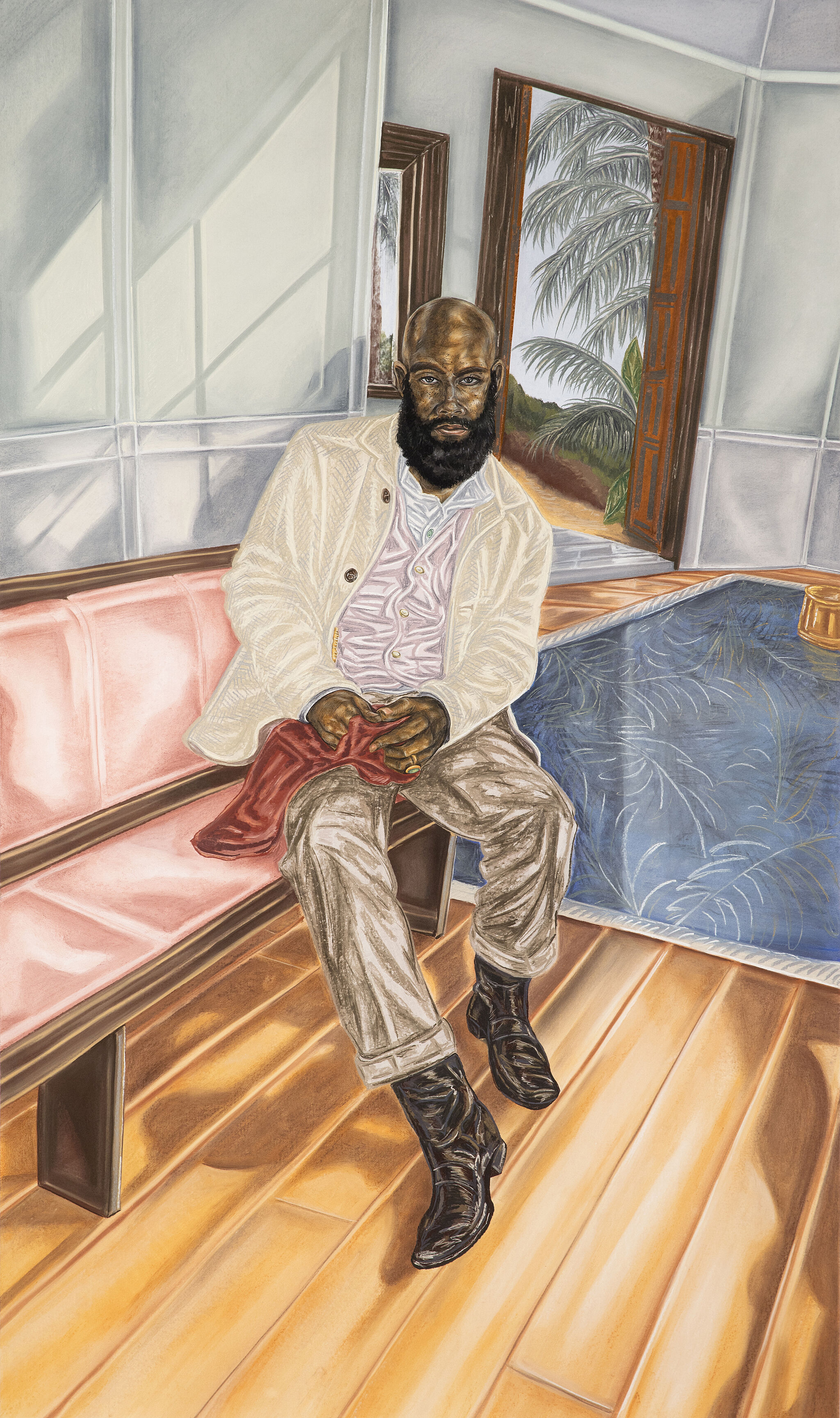

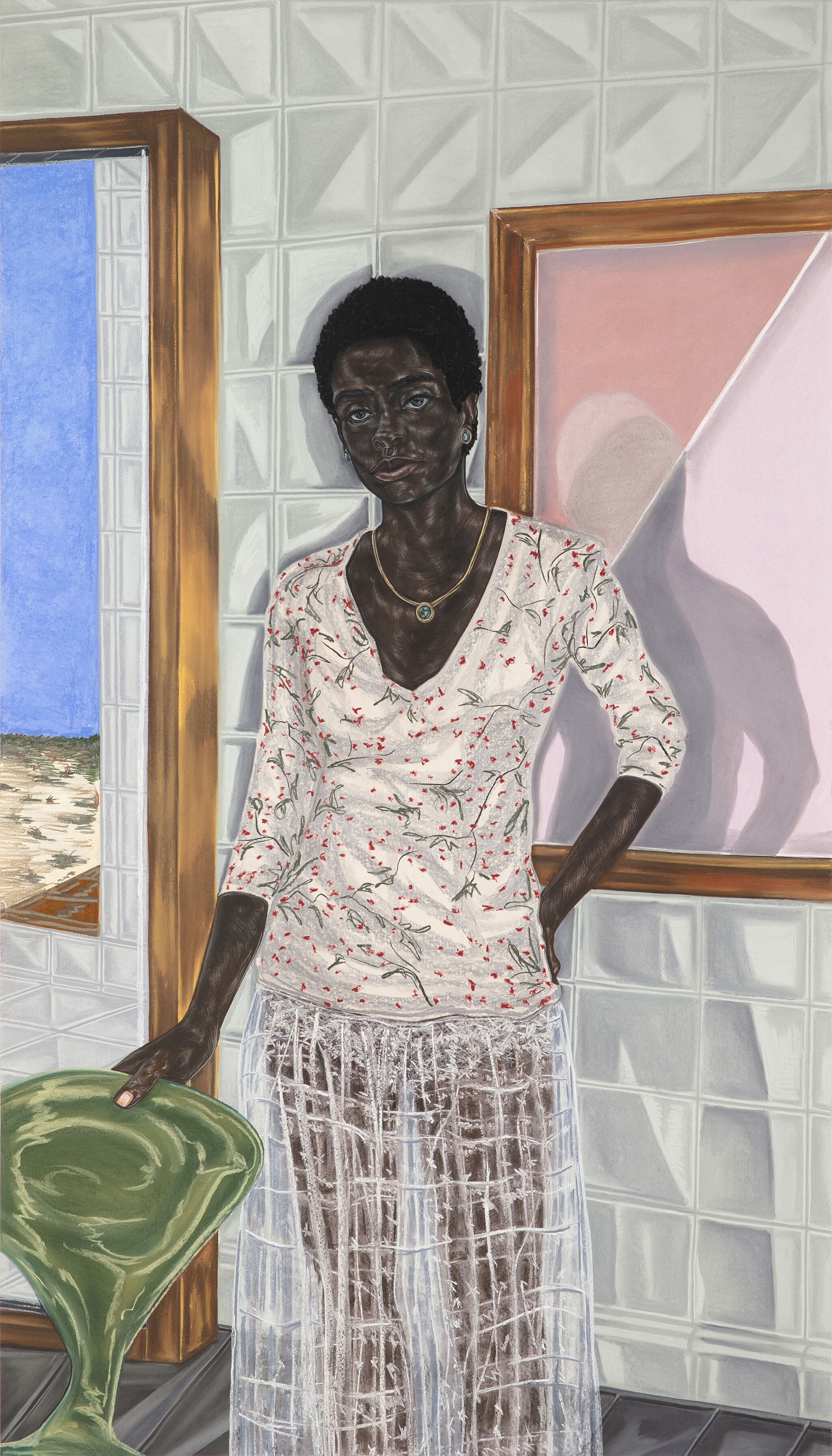

Like members of any family, the individuals depicted in To Wander Determined have divergent opinions and points of view. Their interactions are open-ended and subject to interpretation, but as onlookers we are more voyeur than participant. We aren’t quite sure how they feel about each other, what has happened previously, or what might happen later. What is clear, however, is that they are wealthy. Specifically, they are wealthy people of color. In their clothing, surroundings, and bearing, we read access and privilege, though not necessarily as they most often appear. For Ojih Odutola, the utility of attributing wealth to these characters is two-fold. It allows them indifference, the right not to care—something rarely afforded nonwhite people. It allows her the ability to imagine the impossible: a world in which historically oppressed people exist outside of the irreversible and earth-shattering events of the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism. As she says, “What would wealth look like in these countries if they’d been left alone?”Unpublished audio interview with the artist. What would family ties, personal relationships, subjectivity, and individual choices look like? Left to our own devices, we read the signs as rendered by Ojih Odutola and conjure our own explanations.

Representatives of State (2016–17) offers an intriguing prelude. The drawing depicts four statuesque black women of varying skin tones, tastefully dressed and posed in commanding positions. Literal representatives of state, these elected officials seem to have been captured during a momentary break in their duties. Like many of Ojih Odutola’s female subjects, they are strong, ambitious, and intrepid. With their penetrating gazes and almost superhuman aura, they bring to mind guardians or protective deities. If these women are the stoic gatekeepers of their family’s affairs, then in Newlyweds on Holiday (2016) we find the connective tissue and emotional heart. Standing confidently and defiantly, two stylish men appear side by side, their hands gently entwined. Uniquely, their relationship is addressed in Ojih Odutola’s letter, which identifies them as their respective families’ young patriarchs—and as a newlywed couple. Anchoring these historic families, the two are shown in an opulent interior setting with lavish clothing to match. Given that same-sex marriage is illegal in Nigeria, the artist here cleverly subverts the narrative, conflating progressive norms with the actual world in which these families are said to exist, thereby causing us to question both possibility and context.The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act was signed into law by former Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan on January 7, 2014. The law prohibits marriage, cohabitation, and any public display of affection between same-sex partners and imposes prison sentences of up to fourteen years for infractions, which can extend to anyone who supports or “registers, operates or participates in gay clubs, societies and organizations.” See Human Rights Watch, “‘Tell Me Where I Can Be Safe’: The Impact of Nigeria’s Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act,” October 20, 2016, (accessed December 29, 2017). In another marriage-themed work, Bride (2016), a woman wearing a veil and a dress with a high, Victorian-era neckline is shown in close-cropped profile. We may assume that she is the bride of someone in the room, perhaps offering another tantalizing storyline; when searching for her match, however, it becomes clear that this kind of continuity has been deliberately obscured. Although incredibly rich in detail, the storyline is episodic and ultimately incomplete. Moving forward and backward within this fragmented continuum, Ojih Odutola frees her work from conventional narrative structure, despite her use of “traditional” media and techniques.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that Ojih Odutola first worked with ballpoint pen, an inexpensive and accessible medium more closely associated with comics, zines, graphic novels, and other forms of illustration and visual storytelling. While her more recent choice to employ pastel and charcoal harkens back to earlier eras of art-making, Ojih Odutola uses these materials to zero in on the work’s narrative threads while expanding its scale, palette, and content. In some ways, this change has shifted her work closer to Western traditions of painting. Pastels have a long history within portraiture and painting, gaining widespread use in France and England as early as the eighteenth century.Pastels were associated historically with painting rather than drawing, and when they first gained popularity in the eighteenth century, the medium became widely known as “pastel painting,” in part because color seemed to dominate over line. See Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, “The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–), (September 2010). Looking to practitioners like Mary Cassatt, who used pastels widely in the late nineteenth century, Ojih Odutola creates highly finished, heavily layered, painterly passages in her drawings. As with other media, she approaches pastel not simply as a tool for loosely rendered sketching, but as a way to build up layers through shading and blending, often with her fingers, creating a velvety texture deliberately reminiscent of painting.

Despite her work’s many formal connections to painting, however, closer inspection reveals a directness and immediacy that only accompany rigorous draftsmanship, as well as a highly unconventional approach to handling material and surface. In First Night at Boarding School (2017), Ojih Odutola depicts a small boy bundled in blankets against a window overlooking a mountainous landscape whose peaks and valleys appear almost as extensions of the heavy folds and curving patterns of the enveloping fabric. The only elements separating these spaces are the delicately rendered etched-glass windows, which create the illusion of transparency. This convincing division of indoor and outdoor space heightens the palpable feeling of separation and dislocation experienced by the isolated child. Other works, such as Wall of Ambassadors (2017)—a drawing of a salon-style installation of portraits, a series of pictures within a picture—reveal an eclectic range of drawing techniques. Tidy, detailed hatching and loose, broad sketch-like marks appear alongside large swaths of blended color, which contribute to the effects of light, shadow, and tone throughout the work. Bold contour lines suggest pleats and folds within textured fabrics, while a lighter, almost scattered line adds a sense of embellishment to the collar of the central figure. In front of this figure is a lusciously green potted plant held aloft by hands barely visible below. Inexplicably placed closest to the viewer, and perhaps standing in for us, the plant both demarcates space and disturbs our expectations of spatial recession within the picture plane.

Throughout her work, Ojih Odutola draws from an amalgamation of images and motifs culled from historical and contemporary art as well as fashion and design, many of which she finds online or while visiting museums and galleries. The artist regularly posts these diverse sources of inspiration to her Instagram account, treating them as part of an accumulating thread of research for works in progress or not yet made. This social media archive includes an eclectic cache of masterworks by artists ranging from John Singer Sargent, celebrated American portraitist of the late nineteenth century, to Daidō Moriyama, the Japanese street photographer known for capturing harsh, abject scenes of city life in the postwar period, to Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, the contemporary British-Ghanaian painter of what have been called “psychological” portraits. While extracting compositional strategies and themes from various strains of portraiture, Ojih Odutola often looks to vintage fashion to attire her figures, pairing, for example, a 1920s pantsuit with something more current to create a unique silhouette and feel. In tandem with her wide-ranging art-historical referents, such clothing combinations preclude us from pinning down the specific time period from which her figures might be drawn. As the countless sources and influences in her works converge, the artist begins to invent people and places that ostensibly exist in our own reality. She often integrates found imagery with visuals derived from personal memories or from her own informal photography. A building or landscape might be excerpted from her family’s homes in Nigeria or Alabama; in other cases, she draws from locations seen during her frequent travels. Photography has become an especially useful tool for Ojih Odutola in constructing her characters. When referencing an image of herself or a friend, she may splice in a different facial feature or pose, subtly hinting at likeness while creating a new individual and persona. As she develops these composite subjects, she fluidly shifts between the real and the imaginary, inventing and embracing a fantastical, visionary world. In Surveying the Family Seat (2017), a verdant Tuscan countryside is paired with the stark rock formations of the American Southwest, rendered below a billowing sky reminiscent of the expressive style of American Regionalist painters such as John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood. Similarly eclectic contrasts appear in The Missionary (2017), First Night at Boarding School (2017), and Industry (Husband and Wife) (2017), in which portraits rich in mystery and dramatic potential are juxtaposed with seemingly mismatched combinations of vegetation and infrastructure.

The artist’s interiors are also marked by a dreamy, surreal atmosphere. Influenced by Ukiyo-e, or “floating world,” Japanese prints of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, Ojih Odutola frees her compositions from strict perspectival order, animating flattened areas such as walls and floors. A striking example of the artist’s activated, stylized spaces appears in Years Later – Her Scarf (2017), in which a man sits uneasily with the eponymous scarf (presumably from a past lover) clutched tightly in his hands. Instead of receding in perspective, the floorboards slant toward the viewer, pulling us into the composition, while the figure’s magnetic gaze draws us in even further. Through multiple vanishing points, Ojih Odutola throws her compositions off-kilter, creating the effect of an ever-expanding room. Framing devices such as doorways, windows, and mirrors, which often reveal mysterious sightlines, emphasize these deliberately skewed and dramatic angles. In another full-length figure drawing, Unclaimed Estates (2017), a man deep in contemplation leans coolly against a wall. Flanked on either side by an open doorway and a mirror, his body is positioned parallel to the corners of the room, where the angled walls and floors seem to bend in unlikely directions, trapping him within the tight vertical space. The mirror next to him hangs, impossibly, in a corner. Ojih Odutola sneaks in such irrational details throughout, subverting the rules of conventional representation while further pushing the psychological narrative.

Ojih Odutola’s works resonate with feelings ranging from nostalgia and melancholy to contemplation and empowerment. The interiority of her subjects is powerfully articulated through their faraway looks and weary glances, in the drape of a blazer, or by the slouch (or lift) of a shoulder. Engaging with the vast history of portraiture, she reinvigorates a genre that has largely excluded the representation of nonwhite figures through her nuanced examinations of skin color and class. Understanding identity as fluid and multifaceted, she discredits any notion of the self as either singular or fixed. Each of Ojih Odutola’s composite figures, based on an assortment of features and poses drawn from family members, friends, and the artist herself, as well as different emotional and psychological states, can be understood as a “mood,” she explains, rather than “necessarily dealing with a specific person in a place and time.”Unpublished audio interview with the artist.Even knowing this, it is challenging for viewers to resist the urge to identify her figures—to look for someone we might recognize. Drawn in by her subjects’ often wandering gazes, it is easy to become lost in the continuous, sinewy patterns of their skin. Likewise, the intricacies of the imagined backdrop—landscape or interior—spill into the figures themselves, uniting them as one and the same. In many ways, the figures’ surroundings are an extension of their identities—a portrait of the tenor that they evoke. Within the bold, terrain-like patterning, the artist plays with dense layers of exaggerated color and line, implying a sense of movement and malleability—elements symbolic of the mercurial and metamorphic wandering self.