Nick Mauss: Transmissions

Mar 13, 2018

0:00

Nick Mauss: Transmissions

0:00

Nick Mauss: My name's Nick Mauss. I'm an artist.

In Transmissions, I am showing a, a mixture of artworks, documents, and dance-related artifacts that are not usually seen as artworks, but they start to kind of come to the same level and speak with a similar intensity.

Narrator: Transmissions is not a straightforward work of scholarship—“Ballet and American Modernism,” or something along those lines. It’s a work of art in itself—though it includes objects made by other artists, along with sculptures Mauss has constructed, and performances that he has conceived in collaboration with New York-based dancers with very distinct performance styles.

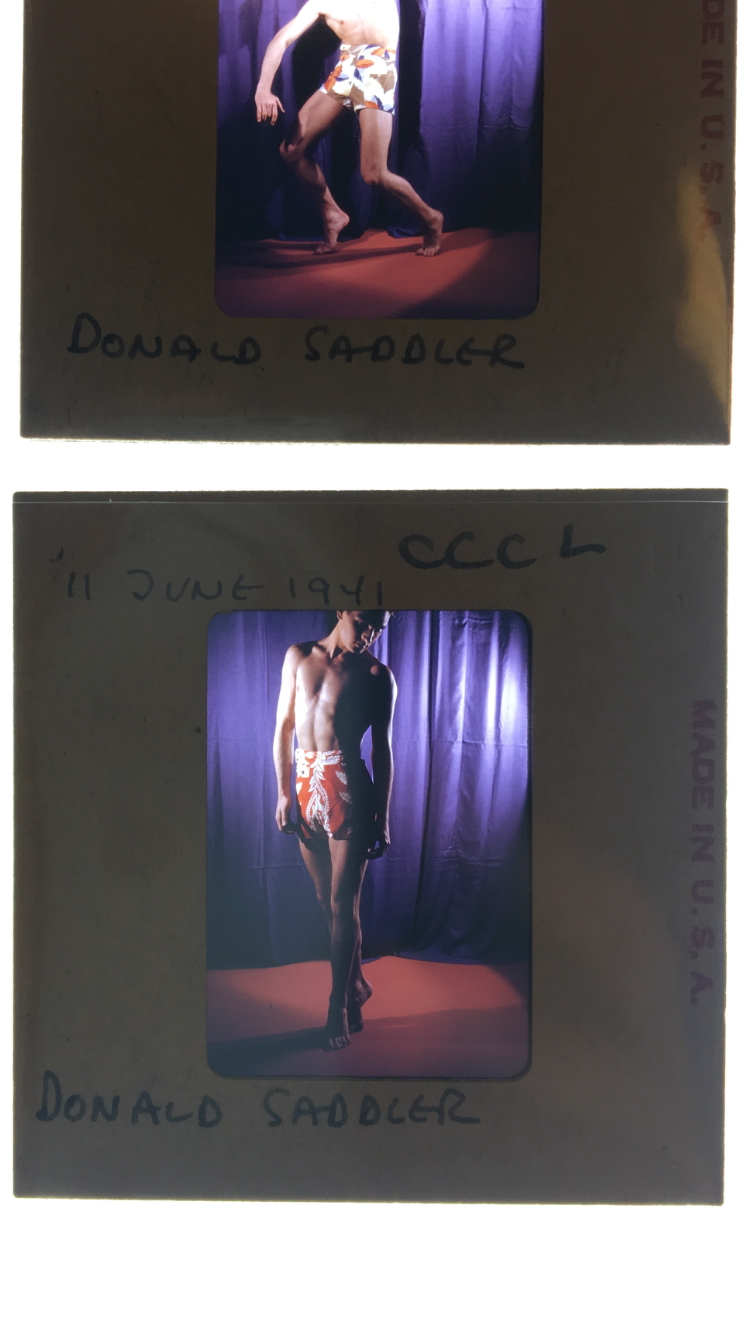

The photographs displayed on the scrim near the entrance introduce a number of the threads Mauss follows throughout the exhibition. They’re by George Platt Lynes.

Nick Mauss: George Platt Lynes was the official photographer for the New York City Ballet, but also a celebrated fashion photographer at the time who produced a private body of work in tandem with the commercial work he was doing that explored a kind of gay erotics, often with dancers as models.

This wealth of photographic material attempts to capture dancers or specific dancers or specific productions—you know, I started wondering, why isn't this image production also a part of art history, or of my understanding of art history?

Parallel to this, I was really interested in a moment in the history of New York that predated Stonewall, and a certain visibility of Queer subjectivities.

I was led to ballet and I found that this was a nexus where people from many different fields could collaborate and work together and exchange, but it was also very important meeting place for homosexual men at a time when it was actually illegal for them to gather publicly.

Narrator: One person who was at the intersection of these developments was the painter Paul Cadmus. In one of the Lynes photographs on the scrim, Cadmus appears in an evocative pose with his lover, the artist Jared French. Cadmus weaves in and out of this installation. In the window overlooking the Hudson, for example, there’s a ballet costume. Mauss re-created it, based on Cadmus’s original.

Nick Mauss: One of the first things you see when you come off the elevator and, and walk towards the entrance to the exhibition is an Elie Nadelman sculpture of a dancer a striking an almost classical pose. It's a sculpture that—like all sculpture—has to be seen from every angle, so it's rotating very slowly in front of this view onto the Hudson, and floating directly above it is a transparent gas station attendant’s outfit, which was a costume for the ballet Filling Station. Those two objects don't really have any linear or logical relationship to each other, but I think they produce a kind of friction.

Narrator: If you haven’t already, please go into the main exhibition, and explore as you listen. Here, you’ll find a dance floor that Mauss has built for performances that take place daily in the exhibition, and a stepped structure conceived as a place for the dancers to stretch, rest, and observe one another, as well as visitors to the exhibition.

Circling the room, you’ll find a number of works of art depicting dancers, patrons of the dance, and the artists—including Cadmus—who collaborated with ballet makers and ballet dancers. Art history and dance history are presented as interdependent. Some works evoke the New York cityscape of the thirties and forties—the place and time ballet really began in this country.

Nick Mauss: I realized that it's a very open form, or much more open than I thought. A lot of people have associations of rigidity and purity, when they think about ballet, but in fact, it's something that's sort of constantly scraping against itself and breaking open and reinventing itself.

There are a lot of old stories embedded in it, but it's also always trying to lurch forward. And in the period that I started to concentrate on, the thirties and forties in New York, you have this European form, mostly associated with Russia that's brought to America. And people are investing it with modern dance, influences from Hollywood and jazz, all these different sources are brought to bear upon this very traditional form. The dancers are, are really seen as major artists, which I also think is kind of amazing, you know, that they’re kind of celebrities of their time, and their artistry is very short-lived, and then it turns into memories and anecdotes and it's sort of handed on.

I think that, the fact that this work can't ever be made into a stable form, but really has to be kind of passed on from one person to another person. That became the core of the project for me.

Narrator: Mauss brought together a group of dancers to think about how that ephemeral art form might be transmitted.

Nick Mauss: The dancers will be performing in the gallery every day from 12:00 to 4:00, and within that time period they'll be performing all the movements that are part of their work as dancers, so they'll be warming up in the gallery, and they'll be doing a bar class, and then they will be performing, in repetition, a new sequence that we've developed together in collaboration in the studio.

There was never any interest on my part to do historical reenactments of these older ways of dancing that I find so interesting to look at, because that's not possible. So we looked at dances from the 1930s to the 1950s. We started talking about styles of performance, and so in that sense they started teaching me a lot about their process. We went to the studio from there, and started trying to incorporate some of the things that we noticed or picked out of this footage, and also some still photographs that we had looked at. We did some exercises where we tried working from still photographs and finding ways to stitch together the moments between the poses.

Narrator: Mauss’s exhibition asks us to think like he did with the dancers—creating our own connections between objects.

Nick Mauss: My hope is that the objects in the show start to almost give way to the relationships that I've tried to highlight through them. That the things that connect these objects—the social connections between the artworks, the anecdotes that bind them—are the first thing to go. But I've tried to actually sort of bring them up much higher. I also hope that that can relate to the work that the dancers are doing, as a sort of active rereading and reconsideration of a vocabulary that we claim to understand has a kind of constancy, but that is continually inflected and sort of catapulted out of itself.