How Surrealism Became Black

Rebecca Zorach

Related exhibition

The exhibition Sixties Surreal is on view September 24, 2025–January 19, 2026.

In The Cry of Jazz, the 1959 film by musician and composer Ed Bland, documentary-style footage of Black life in Chicago alternates with scripted scenes of members of a jazz discussion club, both Black and white, debating the origins of jazz and its connection to Black experience in America. Celebrated today as a trailblazing example of Black avant-garde filmmaking, the film visually layers the constraints of economic hardship with creative lines of flight, in parallel with its Black characters’ arguments about jazz form. Intercut throughout are snippets of musical performances by Sun Ra and his Arkestra, who also provide the film’s soundtrack. The film’s protagonist, Alex, explains that Sun Ra sees his music as “a portrayal of everything the Negro really was, is, and is going to be.”Ed Bland (director), The Cry of Jazz (Chicago: KHTB Productions, 1959), 34 min., 23:25.Although the idiosyncratic musical genius—who now stands as a key progenitor of Afrofuturism—left Chicago in 1961, he made abundant marks there. His demanding and prodigiously visionary approach to music infused the city’s Black and progressive white artworlds with imaginative possibilities.

What happens if we view Sun Ra as the center and not the periphery of Chicago’s sense of itself as a surrealist city? Many artists followed in his footsteps. Arkestra percussionist and artist Ayé Aton covered interior walls around Chicago’s South Side with futuristic abstract murals. The Art Ensemble of Chicago followed Sun Ra’s fantastical and futuristic lead by donning flamboyant costumes and facepaint, intertwining their musical performances with poetry and theater, and weaving together past, present, and future to dissolve temporal boundaries. The street-corner speaker KeRa Upra preached cosmic mysteries, interspersing oratory with the sound of his modified kazoo, and painted surrealist allegories of Blackness. And beyond Sun Ra’s direct influence, the inspiration offered by Black music unites many of Chicago’s key artistic movements in the decades that followed The Cry of Jazz and offers critical insight into the broad and deep conjunction of surrealism and Blackness in the city.

To ask what is “Black” about Chicago surrealism might also require asking what is surrealist about Chicago, or what is Chicago about the threads of surrealism woven into the art of the American 1960s. Many artists, both Black and white, who explored surrealist tendencies in their work of the period had a connection to the city, from H. C. Westermann to Benny Andrews to Claes Oldenburg to Nancy Spero to John Outterbridge. They came from Chicago, studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, or in some significant way spent time in the city. In 1987, Chicago gallerist, writer, and curator Katharine Kuh would characterize the city’s artistic styles as surrealist: “Because life is so difficult, in order to live in Chicago you turn to something that is unreal, like surrealism, which is, after all, unreal realism.”Katherine Kuh, quote in Avis Berman, “An Interview with Katharine Kuh,” Archives of American Art Journal 27, no. 3 (1987): 2–36 13.Artistic culture in the city also vibrated with the legacy of Jean Dubuffet’s famous lecture “Anticultural Positions,” given at Chicago’s Arts Club in 1951. The French artist, promoting a sensibility strongly marked by Surrealism, assailed European “culture” and advanced an everyday aesthetic: “The culture of the Occident is a coat which doesn’t it . . . I think this culture is very much like a dead language, without anything in common with the language spoken in the street.”Jean Dubuffet, “Anticultural Positions” [1951], in Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, ed. Kristine Stiles and Peter Howard Selz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 192.

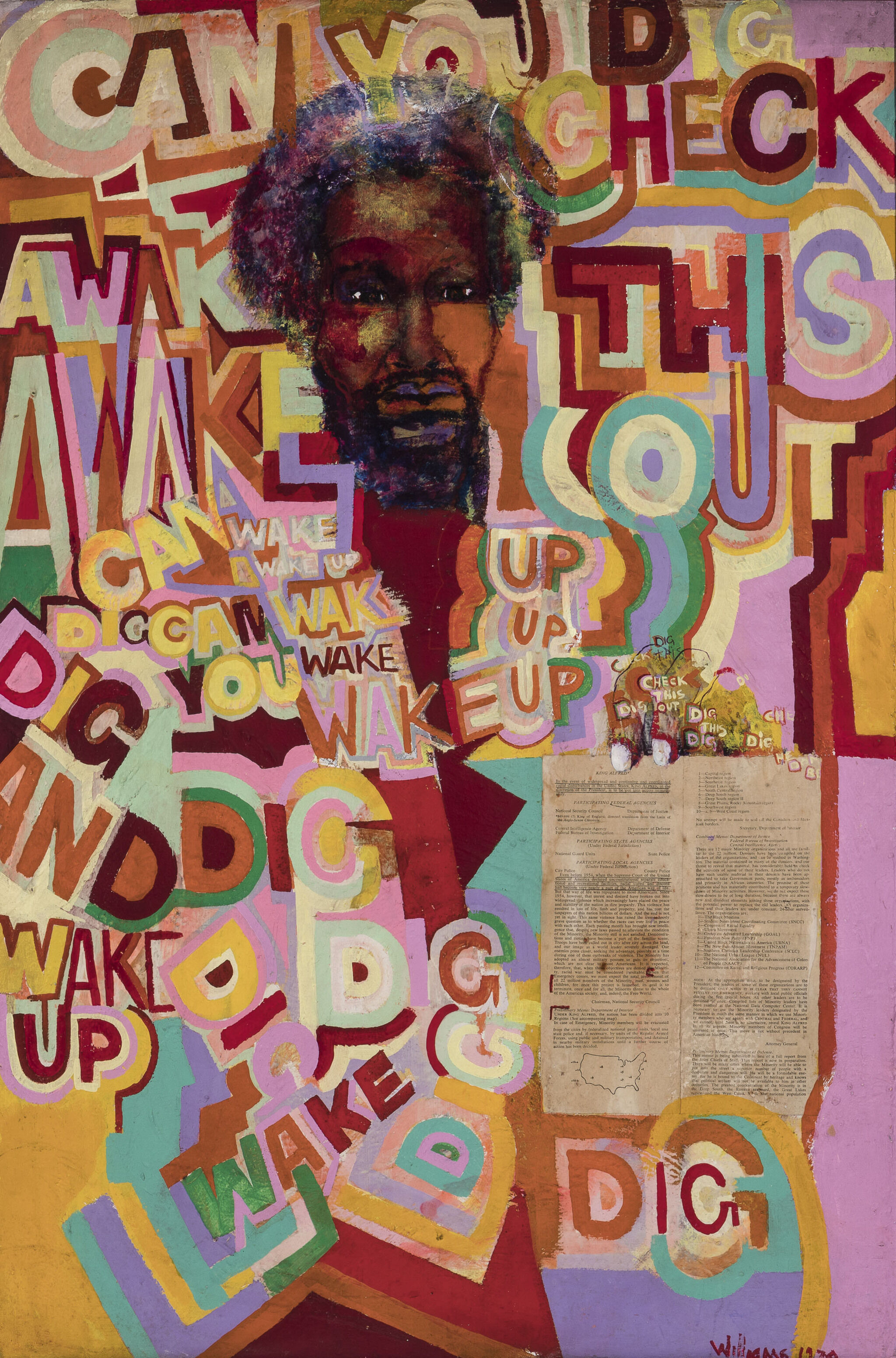

Artists in Chicago set out to find the artistic language spoken in the street, and the inspiration they found was not limited to social documentary. The street was not just the gritty “real.” It was fantastical too, weird and lush and inflected with the expansive genius of Black music. Blackness and the “street” were, of course, not identical, but street life had particular significance in Black Chicago. The intensely crowded housing situation of segregated Bronzeville, the city’s historical Black neighborhood, pushed people to conduct their lives outside whenever possible. Art in the form of mural making took shape on the streets, in the company of a broad swath of community members. The artists of AFRICOBRA, a group born partly out of the experience of creating The Wall of Respect—a major 1967 mural and public event—also took cues from street life.On The Wall of Respect, see Abdul Alkalimat, Romi Crawford, and Rebecca Zorach, The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2017).The “coolade colors” they chose to emphasize in their work came from the fashions they saw people wearing. Artists incorporated graffiti and posters and the remnants of social encounters into their work, as in Gerald Williams’s 1970 painting Wake Up, into which the artist collaged a political broadside he was handed on the street.

The liveliness of the street resonates in Gwendolyn Brooks’s comment that living as she did in Woodlawn, at 63rd and Champlain, if you wanted a poem “you only had to look out of a window. There was material always, walking or running, fighting or screaming or singing.Gwendolyn Brooks, Report from Part One (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1972), 69.(In this she appears to echo Romare Bearden on living in Harlem: “As a Negro, I do not need to go looking for ‘happenings,’ the absurd, or the surreal, because I have seen things out of my studio window on 125th Street that neither Dalí nor Beckett nor Ionesco could have thought possible.”)Romare Bearden, quoted in “Art: Uptown,” Time, Oct. 23, 1964.Real and imaginary overlapped and overlaid one another. The primarily white artist groups loosely designated “Chicago Imagists,” such as the Hairy Who, also worked the street into their freewheeling, pop culture–inspired compositions. Jane Allen and Derek Guthrie discerned an “urban nostalgia” in the Hairy Who artists’ taste for “old dime stores, cigar stores, lingerie shops, B movie houses, and girlie shows”—that is, the vernacular culture of ethnic white neighborhoods.Jane Allen and Derek Guthrie, “The Tradition,” in The Essential New Art Examiner, ed. Terri Griffith et al. (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2011), 29.

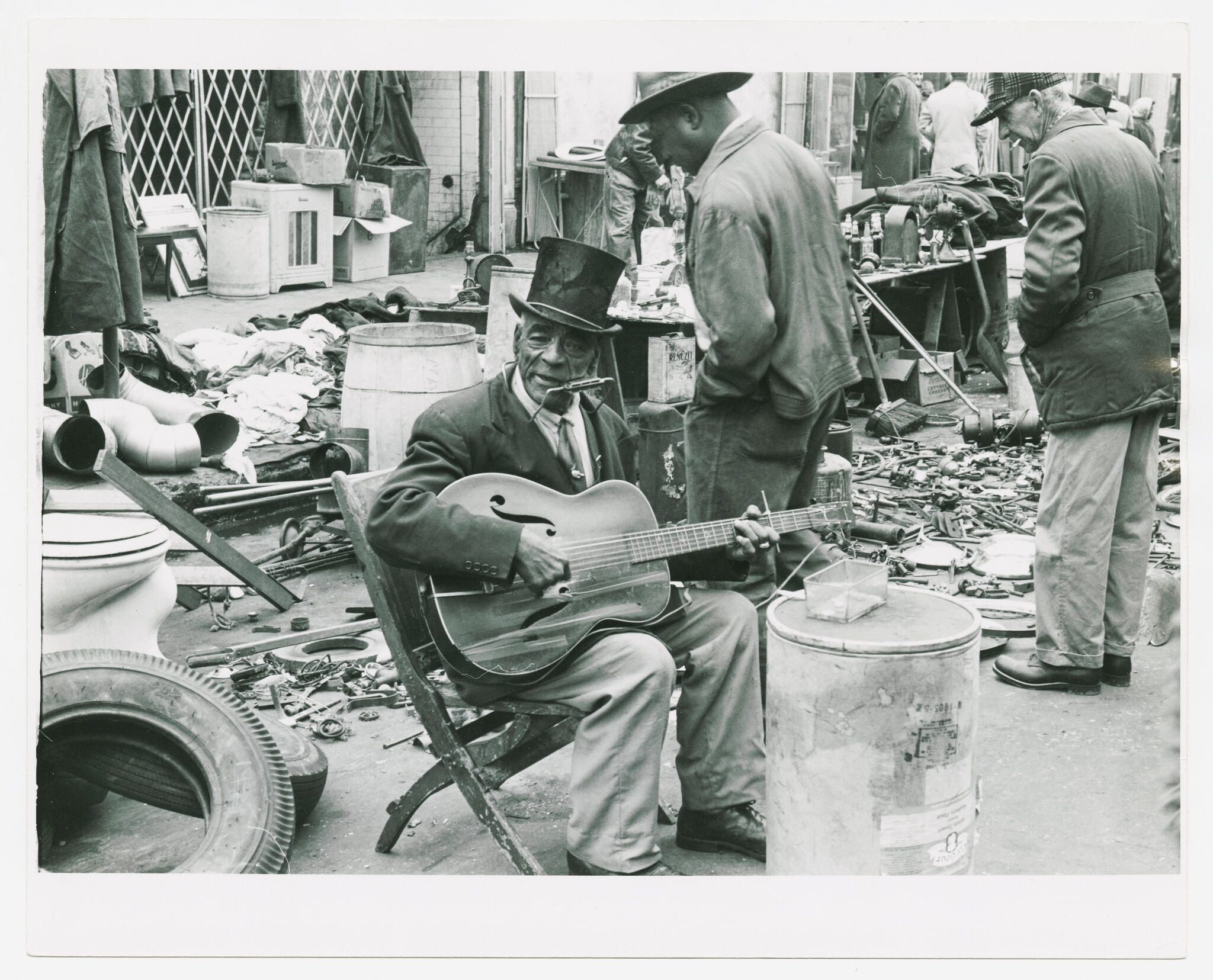

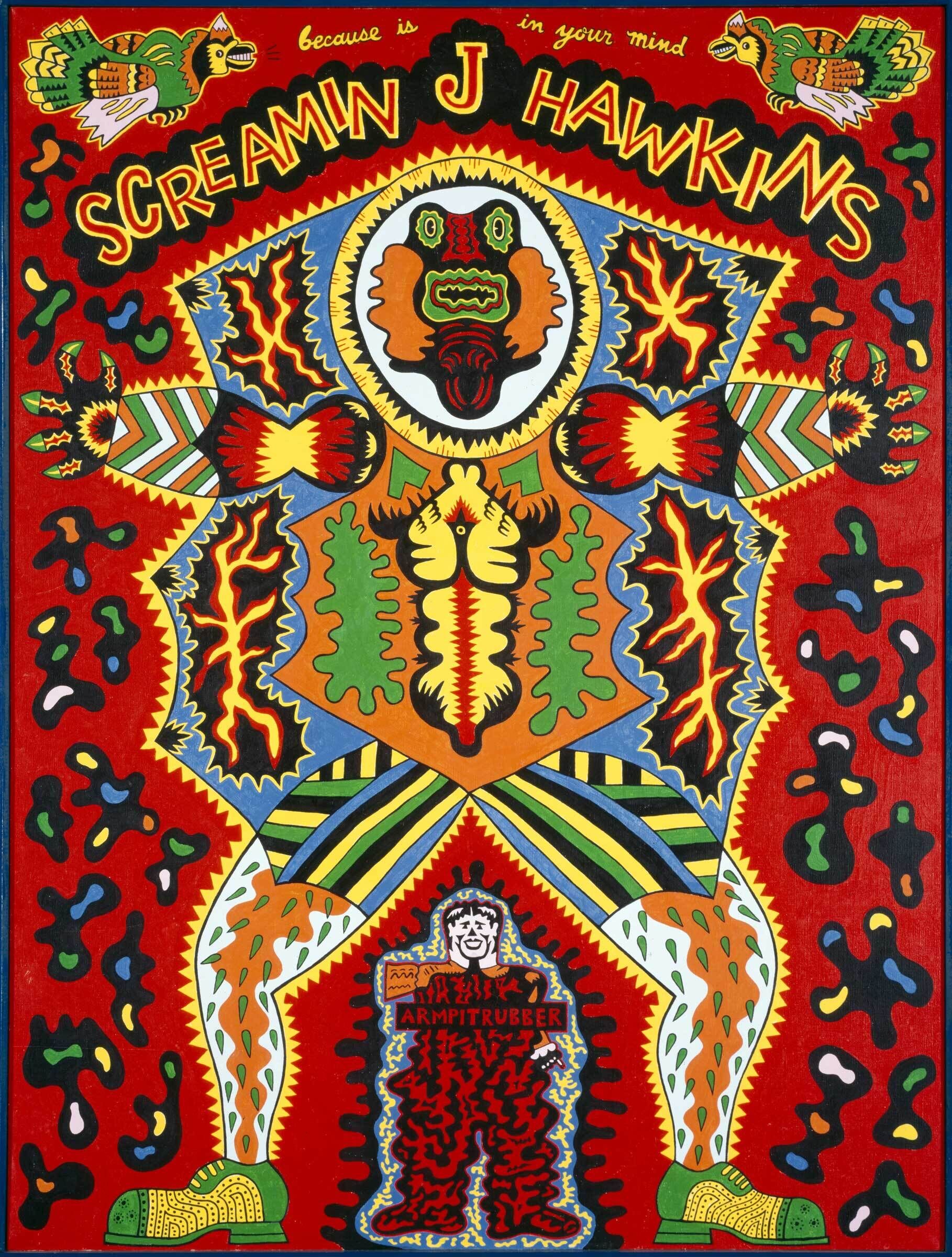

Another of their haunts was the legendary, multicultural Maxwell Street on the near South Side, where they found materials and ideas amid the jumble of discount bulk items and secondhand treasures that were sold informally from pushcarts and from tables on the street. A cultural melting pot since the early twentieth century for immigrant (largely Jewish) and Black communities, Maxwell Street was also the birthplace of the Chicago blues, whose musicians developed its distinctive electrified sound to play over the din of the bustling market. Among the Imagists, Karl Wirsum’s devotion to Black music and theatrical expression comes alive in his intricately vibrant Screamin’ Jay Hawkins (1968).

For many artists who identified as surrealist, the influence of Black music extended beyond its singular ability to capture something essential about the modern urban experience: it embraced demands for revolution. Franklin Rosemont and Paul Garon, for example, wrote extensively on the blues and jazz as surrealist artistic modes, which, as members of the Chicago Surrealist Group (founded by Rosemont and others in 1966), they melded with radical politics.Chicago Surrealist Group, Surrealist Insurrection 1 (January 1968). Available at Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Franklin Rosemont, “Black Music & the Surrealist Revolution,” Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion 3 (1976): 17, 27; Paul Garon, “Blues and the Poetry of Revolt,” Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion 1 (1970): 24, 30.Any mere repetition of conventional patterns and forms, a surrealism that could be defined and historicized, was for them the opposite of surrealism’s transformative, liberatory, abolitionist energies. For these white artists and writers traversing the political moment of the late 1960s, the essential project of making the real malleable and the surreal real not only inspired but obliged affinity with Black liberation movements, with the insurrection that was alive within Black politico-cultural forms. The first issue of Surrealist Insurrection, published by the Chicago Surrealist Group in January 1968, prominently requested donations for the campaign to free Black Panther Party chairman Huey P. Newton from prison.

For their part, Black artists in the 1960s did not necessarily embrace the term surrealism, and it wasn’t for lack of access to its significance. Black Chicago had a cosmopolitan intellectual culture: Ebony and Jet magazines had an office in Paris, and Aimé Césaire’s work was well known and frequently cited in the pages of their intellectual sibling, Negro Digest. Césaire thus offered a ready model for Black surrealism in the realm of poetry. And in an earlier generation of Surrealist-inspired Chicagoans, African American artists—in particular Eldzier Cortor and Frederick D. Jones—held a prominent place. Charles White, who later became famous for his politically engaged social realism, designed a mischievously machinic dancer for a 1937 Chicago Artists Union event poster under the heading “Surrealist Brawl.” But by the 1960s there was resistance to any term or movement drawn from European or Euro-American art, a sentiment that is palpable in Romare Bearden’s observation, quoted above, about his art as a record of street experience. Perhaps we should speak not of the surreal, but of the “superreal.” In his essay “10 in Search of a Nation,” Jeff Donaldson argued that the “superreal” in AFRICOBRA’s aesthetic represented “the superreality that is our every day all day thang.”Jeff Donaldson, "10 in Search of a Nation," Black World, October 1970: 6.The group created “superreal images for SUPERREAL people.” Donaldson insisted on the richly layered realness of the superreal: It represented life as lived, not a purely fantastical surreal, but it was intense, vibrating with luminous color, repeated lines, and text layered upon images. It exceeded reality without substituting for it; as the musician James T. (Jimmy) Stewart wrote, Black art “moved with existence.”Jimmy Stewart, “Introduction to Black Aesthetics in Music,” The Black Aesthetic, ed. Addison Gayle Jr. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971), 77, 91, 80. Stewart’s suggestion came in an essay about the Black aesthetic in music, in which he argued that music forms “the ideal paradigm of our understanding of the creative process as a movement with existence,” meaning “to accompany reality, to ‘move with it’ . . . and not against it, which all, yes all, the white cultural art forms do.” Superreal art forms added dimensions to the real, intertwining with it, taking off from it into other realms—and returning to engage with it, politically and aesthetically. With her poems walking down the street, Gwendolyn Brooks’s gloss on Bearden’s 125th Street almost implies a sense of modesty about her own poetic prowess. But her poetry, never simply “what was there,” opens up luxuriant inner lives that stand in rich dissonance with the drab facts of existence, a doubleness that chimes with the “double consciousness” that W. E. B. Du Bois identified in the subjective experience of Black people in the United States. Through its origins in the dominant society’s violent constructions of Black identity, double consciousness produces unwarranted pain, but DuBois also suggests that it brings with it the insights of a surreal sense of self: “The Negro is a kind of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second sight in this American world.”W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1903), 3.

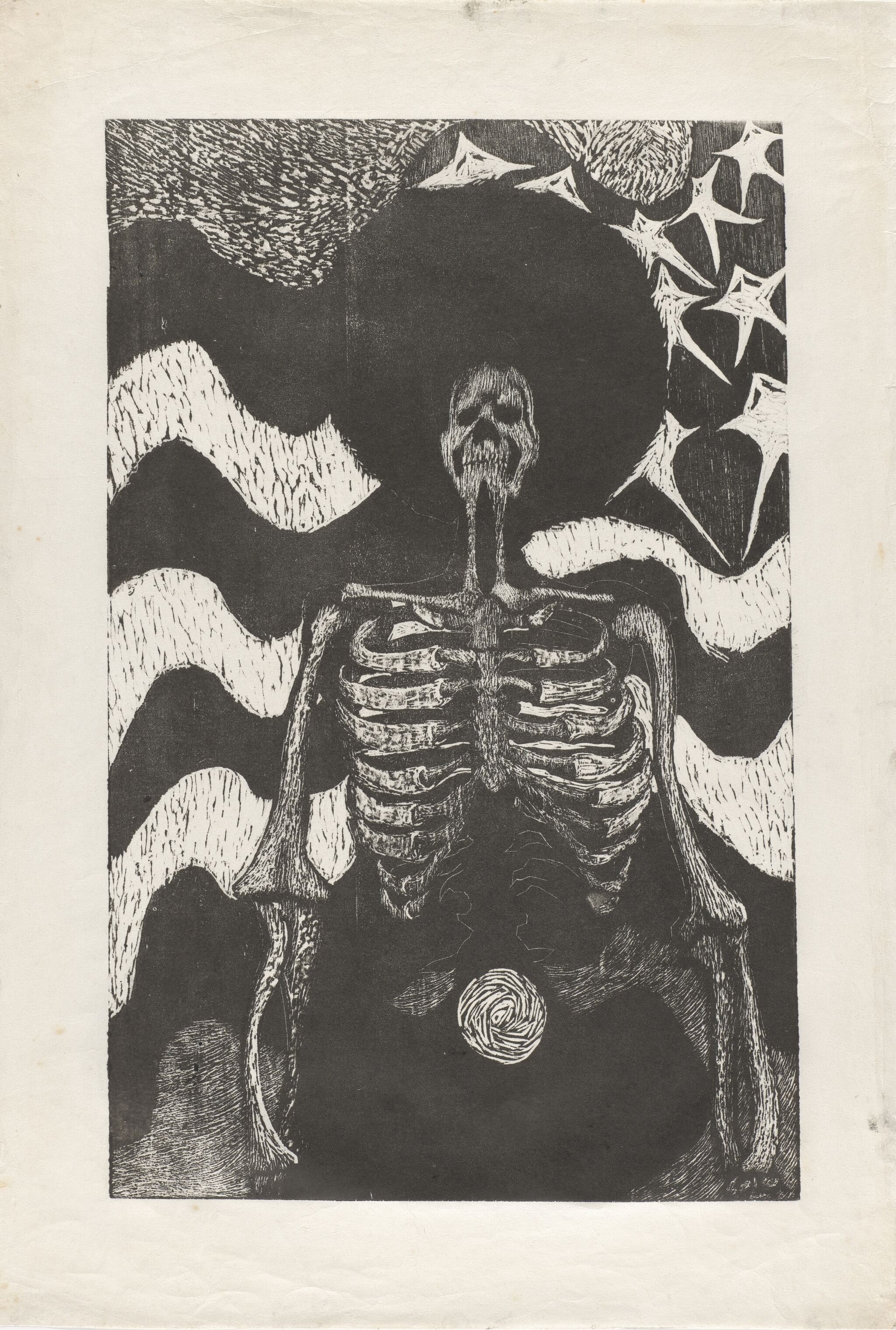

Artists fleshed out the notion of second sight with their own conceptions of the intensity of Black life. As in Bearden’s work, the layering made possible by collage was one way to express the superreal. Ralph Arnold used collage techniques to accumulate news imagery and to comment on contemporary issues. In Donaldson’s J. D. McClain’s Day in Court (1970), the artist collages a newspaper image of the Marin County Courthouse Rebellion of 1970 into a painting that symbolically enhances the events. Donaldson turns the judge in the case into a skeletal figure, adding the word “GLASS,” which he used frequently to refer to white supremacy, and “1A” (bedecked with the Stars and Stripes) for the draft status meaning “available for military service,” perhaps an allusion to the young age of the event’s instigator, seventeen-year-old Jonathan Jackson.See Rebecca Zorach, Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 272. On the use of “GLASS” in Donaldson’s work, see Barbara Jones-Hogu (Barbara J. Jones), “Black Imagery: The Black Experience” (master’s thesis, Illinois Institute of Technology, June 1970), 19.In this case, the superreal adds dimension and interpretation to the documentary “real,” moving alongside it—movement with existence. The layering of real and unreal in The Cry of Jazz serves as a precedent—and in its conclusion it, too, preached revolution. The urgency of rebellion against the Vietnam War—against the US regime’s draft of Black young men in particular—infused Barbara Jones-Hogu’s stunning and complex Mother of Man (1968). Jones-Hogu, a member of AFRICOBRA who trained as a printmaker, developed a figural vocabulary that critiqued US imperialism using skeletons and the American flag, its stripes abstracted into swastikas and its stars into Klan-like hooded white figures. The woodcut, made from a block measuring 24 x 15½ inches, presents a towering skeletal figure who wears a large, deep-black Afro and whose pelvic area contains an abstract coil of white-hot energy. In a contemporaneous description of the work, the artist made clear that she was thinking not only of Black mothers but of their sons, soldiers dying in the Vietnam War: “A black and white woodcut depicting the creator of man. The figure is to symbolize the Black mother’s refusal to give up her [offspring] to die for America’s racist government. The skeleton is the symbol of the death of many young men who have lost their lives.”Jones-Hogu, "Black Imagery," 39–40.In the same text, Jones-Hogu approvingly quoted Bearden’s rejection of the “surreal.”Ibid., 13.But her work embodies revolutionary political arguments in ways that are symbolic and real, gritty and hallucinatory—a vision of the superreal that addresses the political facts of the late 1960s.

This essay is republished from the exhibition catalogue, Sixties Surreal.