Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept | Art & Artists

Apr 6–Oct 16, 2022

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept | Art & Artists

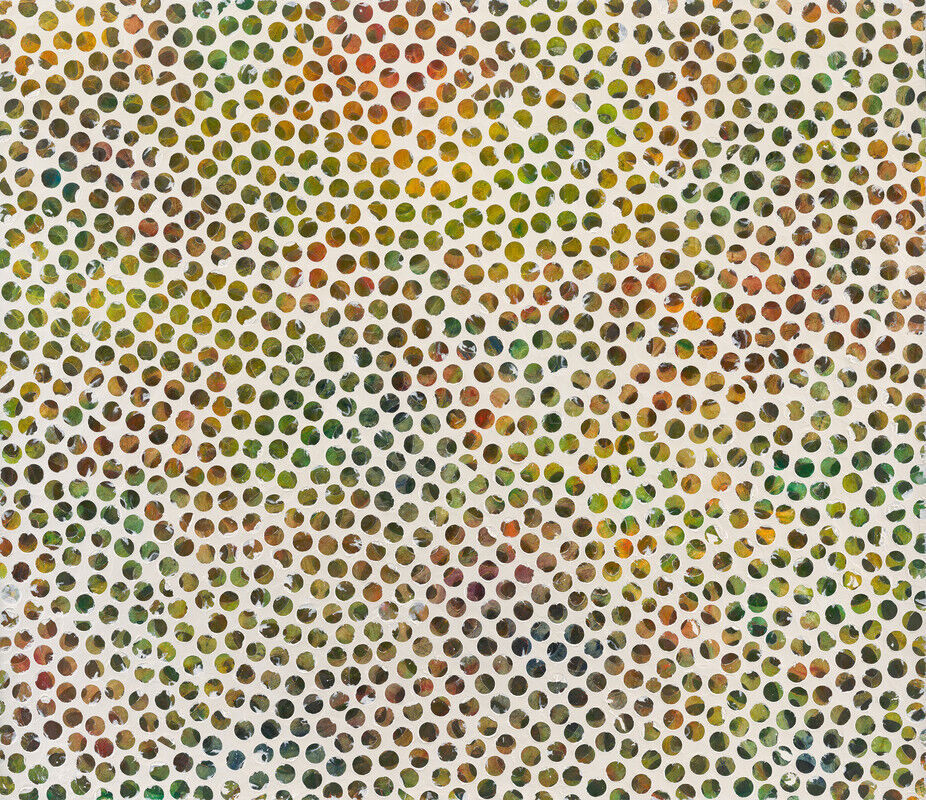

James Little

35

Floors 5 and 6

Born 1952 in Memphis, TN

Lives in New York, NY

James Little is known for making hard-edge geometric abstract paintings such as those on view here. After moving to New York in the 1970s, he was part of a dynamic group of Black artists who were deeply committed to abstraction, including Ed Clark, William T. Williams, Al Loving, Jack Whitten, and Stanley Whitney. As he has written: “What I ascribe to in my art are modernist tenets, without replication or appropriation. I’m not trying to reinvent the wheel. I’m just trying to improve on it. Modernism to me is like democracy. They’re these fragile experiments, these fragile structures that have held up, and they have to keep being supported one way or another, aesthetically or politically. Abstraction provided me with self-determination and free will. It was liberating. I don’t find freedom in any other form. People like to have an answer before they have the experience. Abstraction doesn’t offer you that. It’s up to you. You have to determine the outcome for yourself. That’s why I do it.”

Borrowed Times, 2021

-

0:00

James Little, Joyful Austerity

0:00

Narrator: Artist James Little.

James Little: I don’t find self-expression, and freedom of expression, self-determination in any other form other than abstraction. You want to know why I did this, how did I do it, and what does it take to arrive at a point like this and, it takes a lot of pain . . . takes a lot of discrimination it’s a big struggle, it takes a lot of hope and determination, and those are the things that I try to bring to my painting.

Modernism to me is like democracy. You know it’s these fragile experiments, these fragile structures that have held up and they have to keep being supported one way or another aesthetically or politically. But they are structures and so that’s one of the things that I try to pursue in my art. I always go for structure.

It has to have a feeling. But the thing that makes it work in the end, is whether or not it has synthesis.

An artist, to me, is just a conduit. I mean information is here . . . it travels through him so that we can get this art.

-

0:00

James Little, Exceptional Blacks

0:00

Narrator: James Little grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, in the 1950s. He and his siblings were prohibited from attending the school right across the street from their house; it was restricted to white students only. His parents taught him lessons about survival in the segregated south.

James Little: I mean the way I grew up you’re not encouraged to become a visual artist. You know that’s off the charts—that’s not even an argument. You try to learn something practical. Because your whole thing is to try to get financial security.

Narrator: After earning an MFA at Syracuse University, Little moved to New York and delved into modernism and his career as an abstract painter. He’s been painting for nearly fifty years since then. Recently, Whitney curator Adrienne Edwards visited him in his studio and talked to him about how he makes his white paintings like this one:

Adrienne Edwards: So, Mr. Little. Will you about how you make those white paintings?

James Little: Okay I’m gonna give you, step-by-step technique. So if you took a piece of paper and you want to draw some circles and you cut them out okay so, then you have a stencil. What’s left is a reversal. So I take what you cut out, put it on the canvas after I worked the surface, put it on the canvas, I may paint over it then I’ll take it up. So what I take up is what you see.

Adrienne Edwards: Do you paint, sort of all over? The variation in color?

James Little: Not the same color.

Adrienne Edwards: No, no, I know, but is it the total surface of the canvas?

James Little: I only want the shape of what was there. It could be a square or circle or triangle or or whatever.

Adrienne Edwards: And then you paint it white.

James Little: No, I paint over it take it up.

Adrienne Edwards: I see.

James Little: And then I allow it to dry and I go back over. I go over the white surface with something else or color or mark making or whatever and I’ll use another shape. Over that, and I’ll paint over that shape and put it up, so I get another effect, so I have two layers. So then I’ll decide on a combination of colors. And textures and surfaces, and I will find another shape to put down. Now paint over it. But I don’t stop there, I have to mix the liquid paint make the paint into a liquid form and I pour it. And I have to leave it there for a couple of days to set. So, then, I came back and I removed the last shape from the canvas and then everything I did before that is what you look at when you look through those shapes.

Adrienne Edwards: Amazing.

James Little: I have to think about the colors all the way through from the first layer to the last one. So I gotta try to figure out how to organize it, so the painting has to move and you look at each painting it’s almost like a symphony.