Willa Nasatir

Locating the Photographs of Willa Nasatir

Over the past several years, Willa Nasatir has engaged in a studio practice that avoids being dominated by the culturally prevalent digital technologies.In contrast to contemporary photographers such as Michele Abeles, Lucas Blalock, and Eileen Quinlan, who have productively harnessed and privileged digital technologies in their studio-based practices to address the fundamental challenge our digitally dominant culture presents to photography, Nasatir has made images with a related visual affect but without the benefit of digital manipulation. This, I would argue, yields a different sensibility and tactility to her work.At a moment when the medium has turned inward and disengaged from the hand of its maker—and, as a result, is often labeled as being in a state of crisis—Nasatir has pursued a more manual approach, creating found-object sculptures to be photographed, altered, and re-photographed. While routinely playing with our expectations of what we imagine a digitally constructed image to be, Nasatir exploits the possibilities of photography as an expansive platform for experimentation across composition, scale, and process.

In many respects, Nasatir’s approach is mediated through other disciplines—specifically, sculpture and painting. Distinguishing her photography from documentation reflecting truths about the world (she describes her work as “a depiction rather than a document”Lauren Cornell, “Psychic Junkyards: Willa Nasatir,” Mousse Magazine 54 (Summer 2016).), she has asserted the medium’s capacity for formal invention while simultaneously pushing beyond the boundaries of her studio into the outside world. Nasatir maintains a long-standing interest in what she calls “the texture of the city.”Nasatir, interview with the author, June 2017.Many of her recent compositions are distinguished by images and details of (and out of) her studio window, subtly suggesting urban views that locate the photographs in the New York environment in which she lives and works. While her works begin as objects in the studio, they emerge conceptually from dreams or memories, or even art history, while also drawing upon details of things she sees in the city: a woman on the street, a particular outfit, a general impression of the gentrification and persistent change of New York, and corresponding aesthetic.

Two ideas have surfaced repeatedly in conversation with the artist and in my thinking about Nasatir’s work: the phrase “psychic junkyards”See Cornell, “Psychic Junkyards.” The phrase was also used by the artist’s friend Tip Dunham in conjunction with Nasatir’s work.and the notion of painterly abstraction. The former gets to a core idea about her photographs: while they begin as sculptural assemblages in her studio, her images are ultimately intended to reflect some otherworldly, invented place. As Nasatir maintains, “I’m less interested in photography as a medium for depicting the ‘real’ than I am in its capacity to display the otherworldly.”Cathleen Chaffee, Willa Nasatir, exhibition brochure (Buffalo, NY: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 2017), p. v.Although her compositions often originate in dreams or things fleetingly witnessed, they emerge from a psychic space that is tethered to her use of found objects—that is, the detritus of the world we inhabit. The works become “psychic junkyards” as they reflect the things around us and the limitless number of evocations that might result from them. Ultimately, the images suggest a place never realized, only imagined and implied; they are reflections of the world but not strictly about the world.

Equally important for Nasatir has been her engagement with notions of abstraction. While each work retains referential vestiges—a familiar object, an architectural detail, a distinct reflection—the end result is often abstract in its totality, both visually and in terms of any implied narrative. Accordingly, Nasatir shares an affinity with Charline von Heyl (b. 1960), given the ways in which the German-born painter incorporates familiar forms while denying us any clear or straightforward reading of them or of the work more generally. For Von Heyl, any figurative element becomes subsumed into the overall painting. Similarly, Nasatir’s use of discrete objects and elements is ultimately in the service of her largely ambiguous compositions; these items remain present but are never a resolved end unto themselves. As Von Heyl tellingly explains about her work, “a painting can have several flip points, where things, while you are looking at them, shift from one state to another. They have a way of slipping out of your control, which makes them more interesting.”Jason Farago interview with Charline von Heyl, Even, no. 7 (Summer 2017), p. 55.

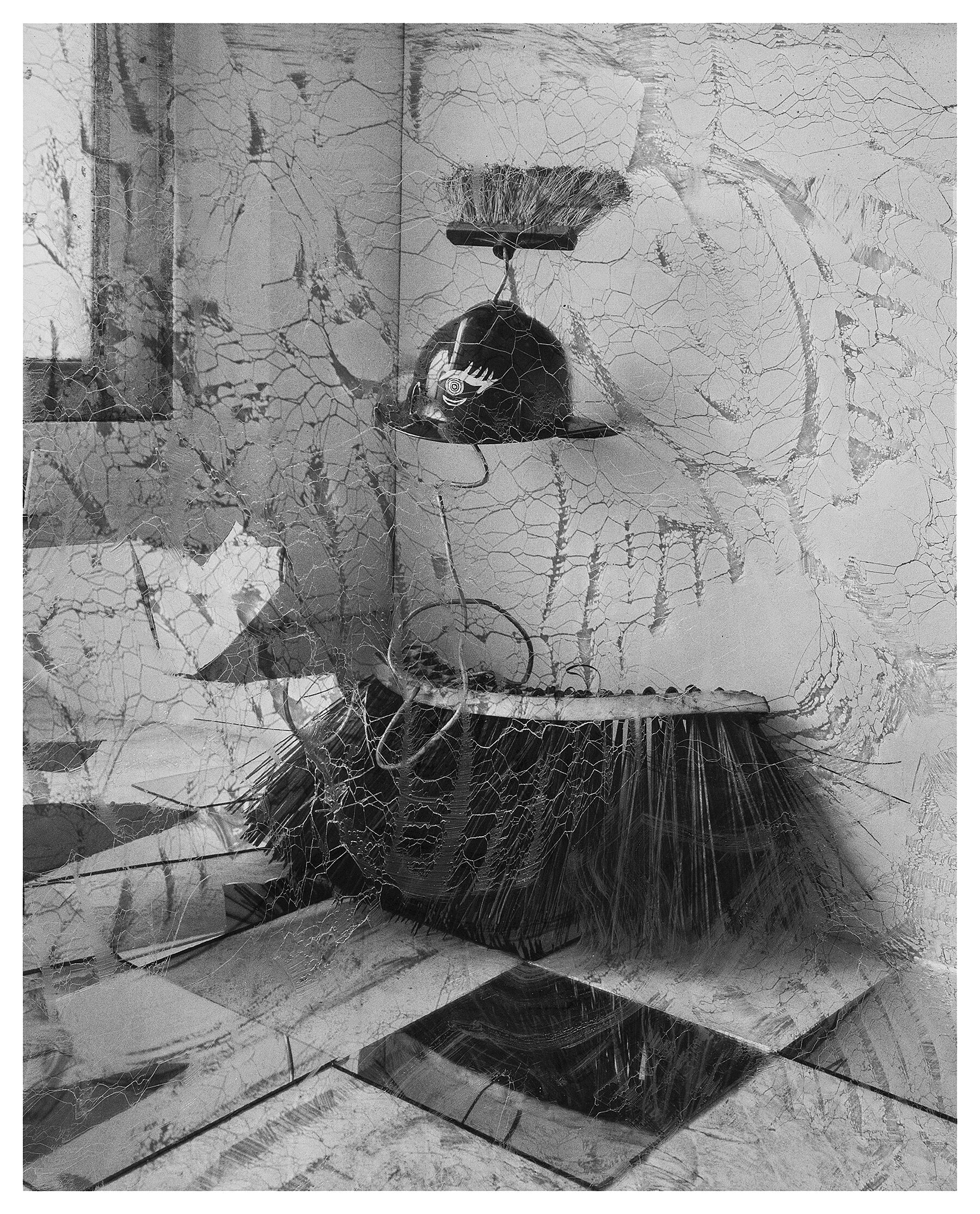

Beyond this implied ambiguity, Nasatir’s photographs function visually in ways similar to paintings, suggesting the value she sees in her medium’s ability to render what might be called figurative abstraction. Many of her immersive images, created at a scale that few contemporary photographers outside documentary or landscape have pursued, immediately imply a spatial relationship to painting. After creating and photographing sculptural compositions in her studio, Nasatir routinely alters the surfaces of her initial prints and re-photographs them to generate the final work, often experimenting with materials such as latex and Plexiglas to create partially obscured or highly reflective surfaces with deliberate imperfections that abstract the overall composition. These unorthodox techniques produce an almost painterly scrim through which the image must be deciphered. Nasatir’s compositions thus bring to mind the complex, layered, and highly worked surface of an abstract painting where the viewer is left struggling to determine which brushstroke came first amid interconnected layers of paint, here mimicked through her multiple layers of photographic process.

Nasatir’s works also incorporate critical historical precedents of her medium, particularly through her nod to photography of the 1930s and 1940s. This relationship is especially apparent in a series of silver gelatin prints debuting here at the Whitney and largely installed together. Nasatir produces these images at a more conventional size of roughly twenty by twenty-four inches, referencing historical photography through technique, scale, and even the experience of viewing the works. While the visual vocabulary of her gelatin prints is similar to that of her larger-scale work, she forces a more intimate engagement with each photograph as the viewer must approach the image—almost as a portal—to experience its myriad intricate details.Nasatir acknowledges the influence of a work like Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage . . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . . . ), 1946–66 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), on these smaller-scale prints. Much like the way in which Duchamp forces the viewer to peer into his invented tableau, Nasatir’s works function as transportative portals that present a highly constructed yet contained space.The monochromatic nature of these works results in an all-over quality that is unique within her practice; each image seems to function as a single, unified moment within the mind’s eye. Unlike in her larger, chromogenic prints, where Nasatir uses disparate colors and objects to clue us that she has drawn from many sources and ideas, here she suggests an encapsulated moment—a single memory or idea that is arguably more fictionalized than factual. (Creating black-and-white photographs allows Nasatir to distinguish these works fundamentally from the reality of what we actually see with our own eyes.) Ultimately, her exploitation of scale and medium enable her to complicate the delivery of ideas and references, as these experiments in black and white become what she describes as a sub-medium of her own photography.

Nasatir’s explorations of the formal possibilities of black-and-white photography is perhaps most specifically related to examples by Man Ray’s contemporary and student Maurice Tabard (1897–1984). Tabard trained as a portrait photographer and worked extensively as a commercial fashion photographer, an important experimental platform for the development of the medium at the time. What frequently resulted were dreamlike works that made use of both the female body and domestic or mundane objects, fused into surreal, unsettling tableaux. But a distinguishing factor that links Tabard’s approach with Nasatir’s is the sophisticated layering effect he achieved, through the use of double exposure and developing techniques such as solarization. His most sophisticated works—often containing strange, spectral silhouettes—yield complex arrangements that become difficult to parse given his ambitious technique and the visual elements that comprise each photograph.

Nasatir’s work shares visual affinities with that of Tabard and his Surrealist colleagues such as Man Ray, both stylistically and through her use of unconventional photographic techniques (particularly in the face of what is available digitally), as well as her de-emphasis on photography’s indexical capability. Arguably, her works in this vein take these qualities and techniques to a new level. Whereas much of this earlier photography emphasized the medium’s relationship to composition and only loosely played with ideas of materiality and texture, Nasatir foregrounds these elements acutely. There is an unsettling handiness to the strange, almost inexplicable sculptural arrangements that appear in her work, and that serve as essential points of origin for her compositions. The tableaux she composes and the photographs she produces from them seem hastily assembled and almost deliberately dysfunctional. While committed to formally imparting the technical acuity of historical precedents from this emergent moment for photography, Nasatir implicitly denies the cool, transcendent slickness of these Surrealist images, seeking instead to depict “something eroding or precarious.”Nasatir, interview with the author, August 2017.Her hyper-materiality maintains a deliberate connection to the world we inhabit and the detritus of lives lived, here reimagined amid a certain level of chaos and visual noise.

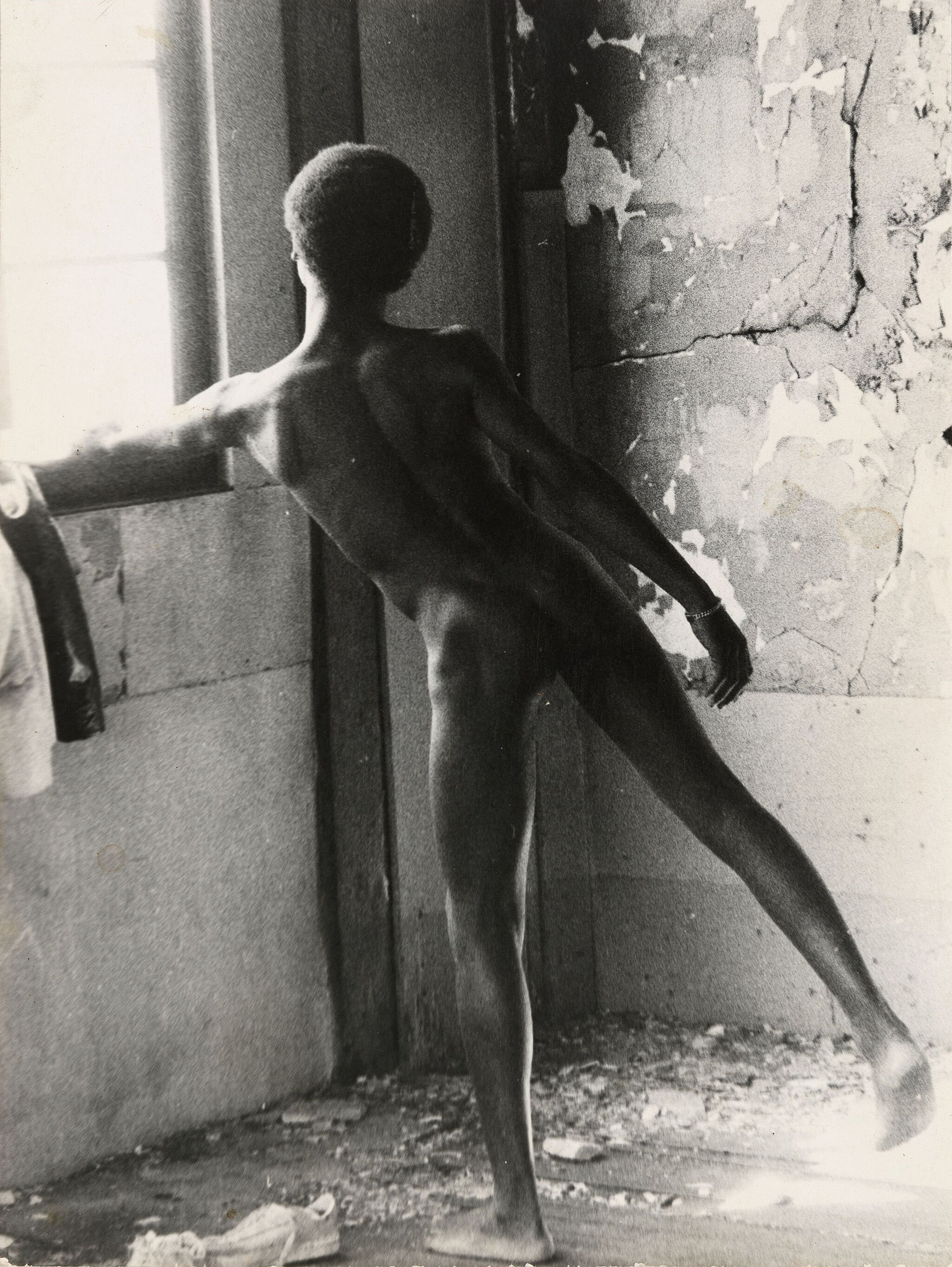

The photographs of Alvin Baltrop (1948–2004), who famously documented Manhattan’s West Side piers in the 1970s and 1980s, and specifically its gay cruising culture, are an important body of work for Nasatir. Baltrop’s images—primarily in black and white—are perhaps more often read as documents of a now-disappeared New York, but they also suggest an otherworldly realm through their textures and unique sensibility.See Valerie Cassel Oliver, Alvin Baltrop: Dreams into Glass, exh. cat. (Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2012), p. 15. As Oliver notes, “Baltrop would continue to create texture with a palette of light and shadow for much of the decade that followed. . . . The artist would reprint negatives until he achieved the texture and emotional tenor he sought.”(In this, they indicate the haven this space represented for the gay community from the harsh reality of persistent homophobia at the time.) Many of Baltrop’s figures seem to float in unreal spaces. He presents us with surreal images that, while based in the documentary, equally point to something imagined or dreamed. While the photos are essential documents, often of beautiful male bodies lovingly and erotically intertwined, they become utopic images suggesting an open-ended invitation to free love. The anonymity of the figures in many of the photos is an essential element, implying some hoped-for future; many of Baltrop’s images are portraits without specified people, much in the way that Nasatir’s photographs suggest portraits but never a figure or specific presence. “I think it’s possible—if not more seamless—to depict the felt experience of the body without showing the form of the figure itself,” Nasatir has said. “I think I’m most successful at it when the figure is androgynous, faceless, abstracted, or even disfigured.”Drew Sawyer, “Willa Nasatir’s Spectral Images,” Document Journal (September 21, 2015).Similar to Baltrop’s interest in personifying the piers as places that evoke a particular moment, Nasatir has consistently implied figures and even narratives without ever creating a straightforward portrait. And for both artists, the ruined or decaying object has been a productive means to eliciting these ideas.

Some of Baltrop’s most dreamlike (though perhaps least iconic) photographs are images taken from within buildings along the piers, with figures lurking only at the edges, if at all. In these examples, the windows frame views onto the Hudson River or the piers themselves, many of which were soon to be demolished. Baltrop’s poetic documentation seems to acknowledge the sanctity of this location, likely to disappear and already heavily in ruins. And notably, these photographs share a recurring element within Nasatir’s works, present in some of her new series of images made specifically for the Whitney exhibition. Nasatir regularly works from her studio, often leaving the viewer with few clues as to where a photograph was made; these are studio photographs about composition, decidedly less about place. However, in a number of instances Nasatir includes—often in the corner of her composition—a clear detail of a studio window, looking out onto buildings that we somehow know are New York. This is no accidental or arbitrary addition. Nasatir openly acknowledges the significance of New York within her work—and particularly her interest in the aspects of the city’s culture slowly being lost to gentrification.Nasatir has had a long-standing interest in the changing face of New York over the past decade, particularly notable in downtown Manhattan where she lives. She routinely references Jeremiah Moss’s blog Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York.And while this preoccupation is not primary to her compositions, it lurks in the corners, imbuing the photographs and objects within them with new significance. Strange found objects suddenly read as items cast off by the city’s inhabitants—possibly part of some downtown culture slowly being disassembled and discarded—suggesting a shared interest with Baltrop in “picturing the city as a vulnerable rather than heroic subject.”Chaffee, Willa Nasatir, p. ii.Nasatir selects what read as inherently urban objects, things of little monetary value but important for the stories they hold. A student of Baltrop’s timely documentation, Nasatir seems to warn us that if we are not careful, the city’s rich and varied fabric—already fraying as we speak—will someday be cast off.

For the Whitney exhibition, Nasatir has produced a six-part installation of large-scale, color chromogenic prints made specifically for the gallery space. The images—which Nasatir describes as “six individual yet interrelated scenes”—introduce a new palette within her work, an almost fluorescent blue-green in addition to the dark, film noir–like overall palette. Nasatir has acknowledged that this highly saturated color represents a notion of the future (as well as a contrast to her previous and recurrent use of red). “There's a certain type of green that I wanted that I hadn't used in a photograph,” she told me. “It reminds me of the ways that the future was depicted in films in the eighties, kind of this neon, spooky green.”Nasatir, interview with author, June 2017.Her comment brings to mind the film Tron (1982), where the “digital” world in which most of the action occurs is depicted as a dark black space punctuated by color, often a deep blue that resembles the palette for Nasatir’s Conductor, 2017. In this composition, Nasatir allows this deep blue to permeate the view we see out of the window, suggesting an immersion in a strange, futuristic, and almost dystopic realm. This distinctive palette becomes one of the unifying compositional elements of her six-part installation, augmenting Nasatir’s ability to suggest an otherworldly future across the tableaux. These colors cue viewers, even from a distance, that we are entering an alternate space.Nasatir is interested in creating photographs that she describes as “looking ahead rather than in the past.” Despite the medium’s logical association with things that have already occurred and been recorded, she strives to signal the future and unknown, and therefore the intangible.

Nasatir’s ambitious installation—as an unexpected hybrid of painting, photography, and sculpture—points to the significance of her work residing within this space of multiple mediums. While the complex legibility of the individual images directly references painting, the works are suffused with sculptural elements, both visual and physical. The installation reads as a physical object or intervention into the gallery: the presence of the six mounted photographs, installed directly against one another, imparts an object-like quality—what she describes as a “solidity”—to these images, placing the work in dialogue with yet another medium beyond photography.Nasatir, interview with the author, August 2017.It is in these liminal spaces—among various media, between the suggestion of form and abstraction, between place and no place—that Nasatir has opened up possibilities for contemporary photography to complicate and to slow down the very process of looking; as a result, her works are never straightforward and are difficult to digest in a single take. As Nasatir explains, “I hope to make work where the experience of viewing is extended, and new meaning occurs with time,”Cornell, “Psychic Junkyards.”reinforcing her sustained interest in the ambiguity of looking through the creation of her unique, photographic conditions.