The Self as Cipher: Salman Toor’s Narrative Paintings

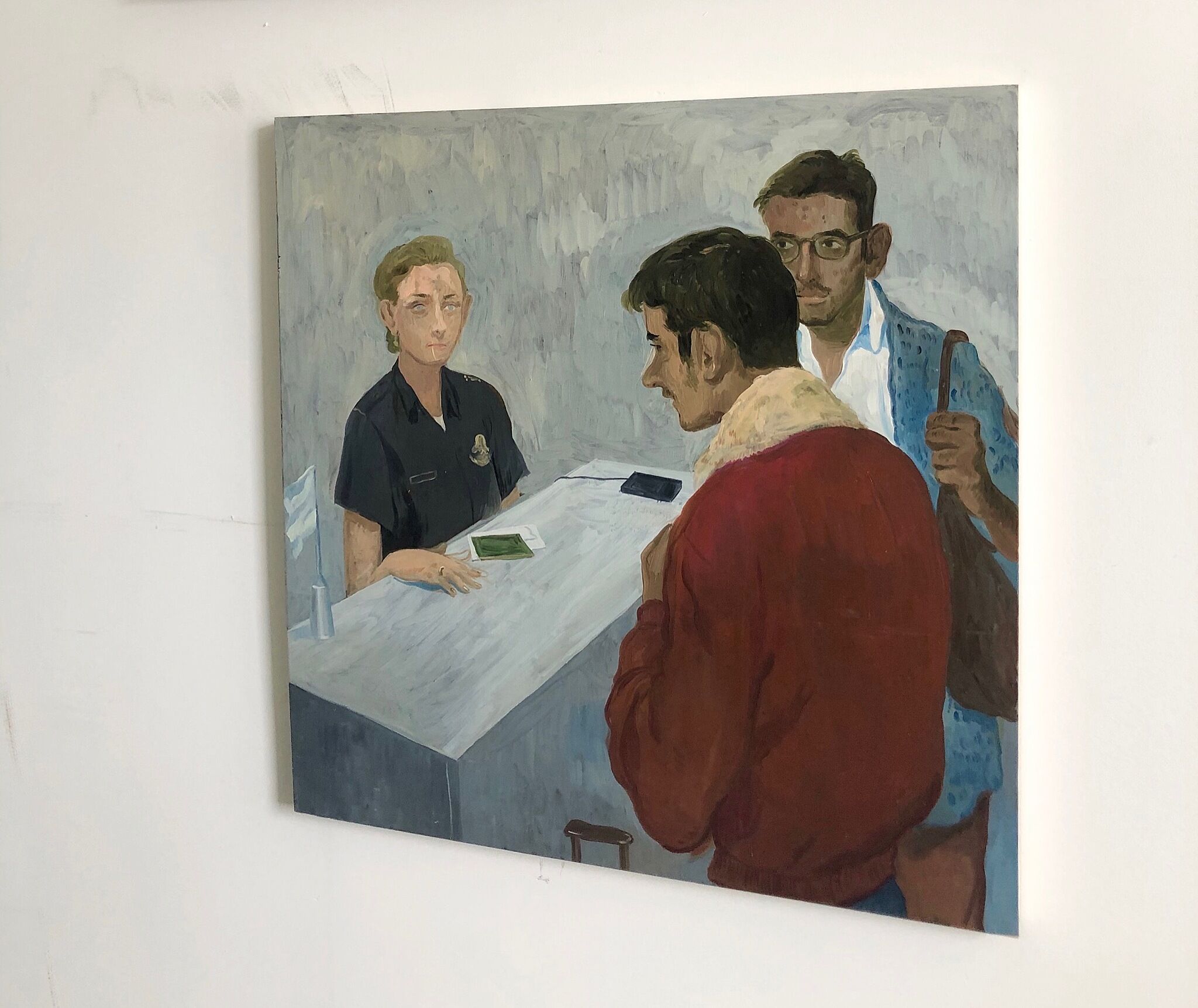

On a wall in Salman Toor’s studio hangs an unfinished painting that the artist made when he was feeling suddenly constricted in his practice. In a move to get more experimental and, in his words, “find some language that would feel consistent and flow out naturally,” he picked up a small panel and without any premeditation, painted a scene that felt wholly familiar.Salman Toor, interview with the author, January 2, 2020. Subsequent quotes by the artist and statements on his practice and influences come from this conversation unless otherwise noted.In it, two men—one resembling Toor himself—stand across from a woman in uniform, clearly an airport customs and border patrol agent. On a table between them rests the agent’s smartphone and a dark green passport, her hand lingering close to the latter.

This was the first time Toor painted a scene so direct and personal. Previously, his work had consisted of larger figurative paintings set in South Asia and created in the style of European Old Masters; expressionistic paintings of sprawling contemporary rooftop parties; and small portraits scattered with speech bubbles and automatic writing in Urdu script. Toor’s art education was in academic painting. He spent years studiously poring over and copying the works of Rococo, Baroque, and Neoclassical-era artists like Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Jean-Antoine Watteau, incorporating their styles into his own original compositions. Over the course of his growing up in Lahore, Pakistan—prior to moving to the United States to earn his BFA from Ohio Wesleyan University (2006) and his MFA at Pratt Institute (2009)—he became deeply knowledgeable about the works of modern Pakistani and Indian painters such as Colin David, Bhupen Khakhar, and Amrita Sher-Gil. Much of his early source material also came from Pakistani advertisements. While those earlier works blended his many global aesthetic references, they did not intimately echo his own experience as a queer Brown man living between the United States and South Asia.

Toor continued the experiment he began with his unfinished painting of two men by making ten other paintings in the same vein but featuring figures that were not him, yet like him. He worked with great speed, holding the brush at arm’s length and moving his elbow more than his wrist to create a sketch- or illustration-like effect. The literal distance between artist and surface of the board allowed Toor to establish space between himself and his subjects. Recalling his surprise at how readily these scenes came to him, Toor says, “I really did not think at all about whether the meaning in these paintings would be coherent to others. I just thought of making something very straightforward to me.” It was only after he hung them on his studio wall and examined the overall result that he decided they did make sense, individually and together. Toor had landed on a unique mode of working: one operating between academic painting and illustration, and between fiction and autobiography.

In recent years, in literature but also in film and visual art, autobiography and memoir have made a notable resurgence. Their present-day variants have sometimes been referred to as narrative essay, autobiographical fiction, or autofiction. Critics attribute the phenomenon to the rise of social media: it is now entirely ordinary for anyone to narrate their own life to a wide audience.On the resurgence of the “I” in contemporary art and literature, see Alex Kitnick, “I, etcetera,” OCTOBER, no. 166 (Fall 2018): 45. On attributing this trend to social media, see Charles Finch, “Autofiction for the Twitter Era: What Tweets and Emojis Have Done to the Novel,” New York Times, November 19, 2019.The diverse writers associated with autofiction range from Rachel Cusk to Ta-Nehisi Coates to Maggie Nelson, all noted for portraying “both their fictional and putatively authentic ‘selves’ as nodes in which social forces intersect.” They examine how the “self” is formed through social constructs of gender, sexuality, and race, as well as “the personal dimensions of capitalism” and class structures.“Between You and Me: A Correspondence on Autofiction in Contemporary Literature between Isabelle Graw and Brigitte Weingart,” Texte zur Kunst, no. 115 (2019): 38, 40.As Alex Kitnick puts it, “the self reemerges . . . not as an origin with depths to be explored but rather as something ceaselessly constructed, mined, and manufactured—a contested site uniquely intelligent about wider systems.”Alex Kitnick, “I, etcetera,” OCTOBER, no. 166 (Fall 2018): 52.

Toor’s narrative paintings featured in the exhibition How Will I Know are likewise autofictions. They are ruminations on the identifications variously imposed on and adopted by queer South Asian men living in the diaspora. Making paintings loosely inspired by his own experiences is a practical strategy for Toor: by thinking of a moment or a friend, his process becomes more meditative, which gives the resulting work a deeply empathetic effect. Smartphones and laptops are as ubiquitous in Toor’s paintings as they are in real life, while references to art history still slip in, instinctively. Of his palimpsestuous view of the world, he says, “I definitely look at the world through an art historical lens, always finding it everywhere.” This is evident in the way he paints the figures’ expressive, noble features and gestures, and the way their curved arms and fingers intertwine and embrace. Other art-historical references—the nocturnal lighting; the stylized lamps, furniture, and clothing; the art on the walls of the depicted apartments—are elements of fantasy that distance the works from the specificities of the artist’s own life. Toor’s rounded, loopy strokes and his manner of building up thick layers of paint seem to embody the generous attention and compassion he extends toward his men, granting them space beyond the board or canvas. These vignettes in which they interact with friends or family, or encounter the various (social, commercial, political) gazes through which they are othered, oscillate in mood between solidarity and alienation.

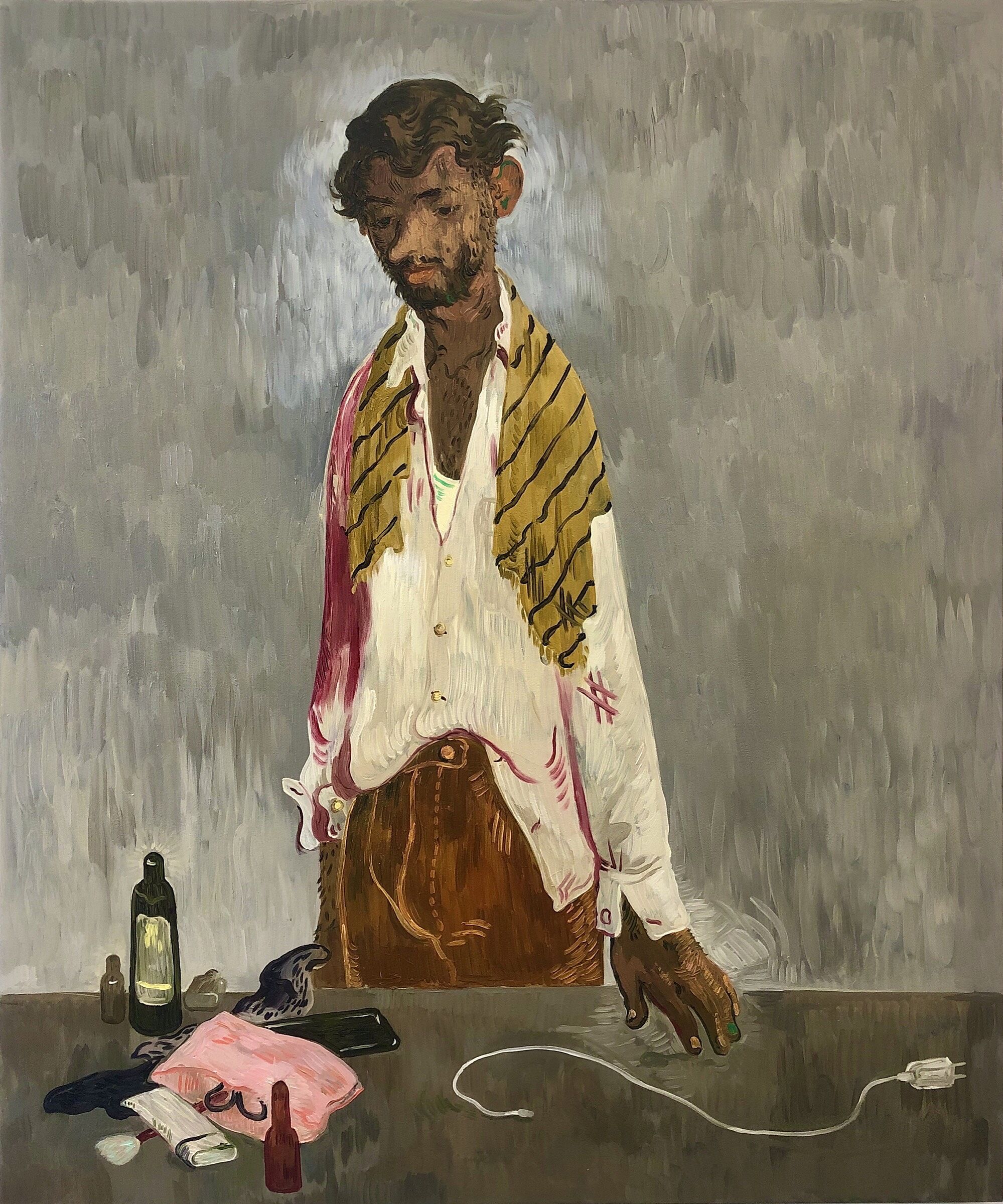

Toor’s ongoing immigration painting series depicts the ways in which Brown men are frequently singled out and scrutinized by immigration and customs officials in the current post-9/11, Muslim ban era.On post-9/11 experience of Muslims in America, see Michael T. Luongo, “Traveling While Muslim Complicates Air Travel,” November 7, 2016. On January 27, 2017, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 13769, titled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States.” It banned foreign nationals from seven nations, five of them majority Muslim (Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen; the others were Venezuela and North Korea), from visiting the United States for ninety days; suspended the entry of all Syrian refugees indefinitely; and prohibited entry of any other refugees for 120 days. Later, other orders (Executive Order 13780 and Presidential Proclamation 9645) were signed by Trump and superseded order 13769. On June 26, 2018, the US Supreme Court upheld the third executive order (Presidential Proclamation 9645) and its accompanying travel ban in a five-to-four decision. See “Timeline of the Muslim Ban,” ACLU Washington.Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug (2019) and Two Men with Vans, Tie, and Bottle (2019), both featured in How Will I Know, are painted from the perspective of the immigration officer so that the viewer’s gaze fuses with theirs. This places the onus on the viewer to consider who the men are, who might be held back for further inspection, and who might be allowed to proceed. The travelers stand with their items—ordinary garments, electronics, and toiletries that could be found in anyone’s luggage—unceremoniously laid out on the table in front of them. The very unremarkableness of the items underscores how national security is too often determined by individuals who make quick judgement calls based on ethnic stereotypes. Meanwhile, the unresponsive and downward gazes of the men, under pressure to appear innocuous to the officials, suggest their refusal to participate in a process that insists on reducing them.

In other paintings, law enforcement lurks around New York street corners (The Smokers [2018]) or peers threateningly into the cars of young men on dates in scenes set in South Asia, where queer identity can render one a criminal in the eyes of the law (Car Boys [2019]).As is still the case in most parts of the world, LGBTQ rights are restricted in South Asia. In Pakistan, the nation’s laws prescribe criminal penalties for same-sex acts. These laws were originally developed under the British Raj during colonial rule, under Section 377 of the Penal Code of 1860. India’s Supreme Court only recently struck down this same ban in 2018. LGBTQ rights vary in other countries within the South Asian region but are generally limited. However, the LGBTQ community is still able to date, organize, socialize, and live together as couples, if done mostly in secret. Regarding trans rights, in 2018 the Pakistani Parliament passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act to establish some protections for transgender people, allowing trans people to register their gender with all government departments based on how they identify. Previously a 2009 ruling by the Supreme Court of Pakistan ruled in favor of civil rights for transgender citizens, and further court rulings have upheld these rights. See Meghan Davidson Ladly, “Gay Pakistanis, Still in Shadows, Seek Acceptance,” New York Times, November 3, 2012.; Jeffrey Gettleman, Kai Schultz, and Suhasini Raj, “India Gay Sex Ban Is Struck Down. ‘Indefensible,’ Court Says,” New York Times, September 6, 2018.; National Assembly of Pakistan, The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2018.; Nadir Guramani, “Senate unanimously approves bill empowering transgenders to determine their own identity,” Dawn, Updated March 7, 2018.In these scenes, Toor’s figures also express passivity in response to being othered. As Homi Bhabha puts it, “Identification is a process of identifying with and through another object, an object otherness, at which point the agency of identification—the subject—is itself always ambivalent, because of the intervention of that otherness.”Jonathan Rutherford and Homi K. Bhabha, “The Third Space: Interview with Homi Bhabha,” in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed. Jonathan Rutherford (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990), 211.In instances in which they are othered, Toor’s characters stand in doorways, on thresholds, or in places of transit; they are unhomed, in a state of displacement, where, again in Bhabha’s words, “the borders between home and world become confused; and, uncannily, the private and the public becomes part of each other, forcing upon us a vision that is as decided as it is disorienting.”Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 9.This sensation is also associated with double-consciousness: the queer Brown figures in Toor’s paintings are aware not only of how they see themselves, but also of how they are being seen, often due to their sexuality and race.W. E. B. Du Bois first wrote of the double consciousness of the Black person in this widely quoted passage from The Souls of Black Folk, originally published in 1903: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”On this point, the artist says, “The act of being perceived by someone can be both liberating—to see an idea of you through someone else—but also really narrowing and debilitating.”

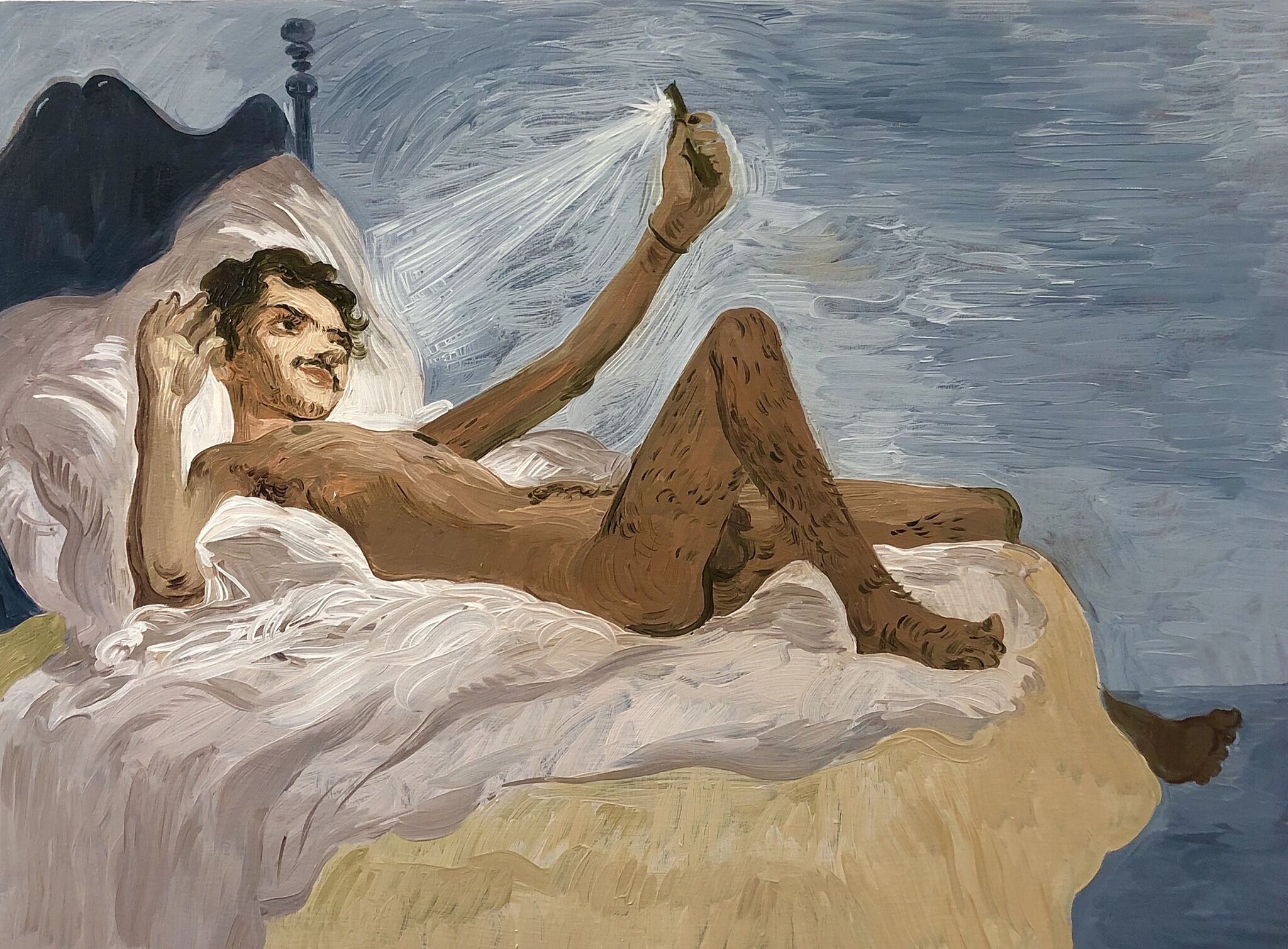

Today, through social media and “the social dimensions of capitalism,” the public world eternally infiltrates the private, further fragmenting one’s self-image.“Between You and Me,” 40.Toor’s Bedroom Boy (2019) depicts a young man taking a nude selfie or perhaps video chatting with a lover via his phone in a staged scene of self-celebration and seduction. Indeed, his bold gaze into the phone camera recalls Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). Yet the nude selfie can also be weaponized against its maker and disseminated without one’s consent or subjected to toxic commentary. This possibility, and the viewer’s knowledge of this, renders the figure even more vulnerable. Meanwhile, in The Star (2019), which seems to channel Titian’s Venus with a Mirror (c. 1555), the central figure looks into a mirror with a mix of apprehension and empowerment as others go about styling him, perhaps for a photo shoot or a public appearance. The work acknowledges the precariousness of relying on aspirational beauty—and the accumulation of likes or hearts—for self-love. In an age where corporations are eager to capitalize on queer people of color by spotlighting them in advertisements and media campaigns to appear more progressive, there is a fine line between agency and exploitation in the name of visibility.Capitalism’s embrace of LGBTQ diversity in the form of rainbow merchandise is referred to as “rainbow capitalism” or “pink capitalism,” and is often viewed with criticism by LGBTQ communities.

Now that self-care has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry and so much of everyday leisure involves participation in consumerism, what is considered authentic and what is commodified can feel inseparable.On the self-care industry see: Christianna Silva, “The Millennial Obsession with Self-Care,” NPR.org, June 4, 2017.Social media plays its part in this by blurring the lines between reality or lived experience and performance or promotion. Toor broaches this type of subject matter not with cynicism, but rather with a mix of anxiety and humor. His paintings also recognize the emotional sincerity that can underlie participating in these actions—for instance wearing makeup or taking a selfie as an act of self-expression, or arranging a puppy play date or binge watching a drama over takeout as a way to bond with friends. By inserting his figures into such scenes, Toor firmly embeds queer Brown people into a mainstream, even privileged, cosmopolitan culture. In doing so, he counters the persistent invisibility—or reductive and predominantly negative portrayals, when they are portrayed—of Brown men in Western media and the art historical canon. “It is to enter Brown bodies into the language of the humanities, symbolized by the European nude,” Toor says of his personal intentions behind these paintings. “But I also enjoy being insolent within that, for instance painting Brown bodies that are skinny or hairy in these privileged spaces.”

Puppy parties and play dates may seem like more Instagram fodder, but Toor’s Puppy Play Date (2019) has different intentions: “I want to re-value Brown people in Western culture by examining their relationships to animals” (an image rarely represented in broader media).Salman Toor, email to the author, October 2019.Toor is queering South Asian representation by inserting a Brown figure into such a tender scene. Looking at the painting, one might tangentially be reminded of A. L. Steiner’s Puppies & Babies (2012), a collage installation comprising a queer archive of photographs of Steiner’s friends, featuring pets, pregnancy, and children—a “reconstitution of images categorized as ‘personal,’ ‘unartistic,’ and ‘cheesy.’” Puppies & Babies complicates archaic notions of family making and, as Maggie Nelson writes in The Argonauts (2015), “places interspecies love firmly on par with human-human love. . . . Indeed one of the gifts of genderqueer family making—and animal loving—is the revelation of caretaking as detachable from—and attachable to—any gender, any sentient being.”Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2015), 72.

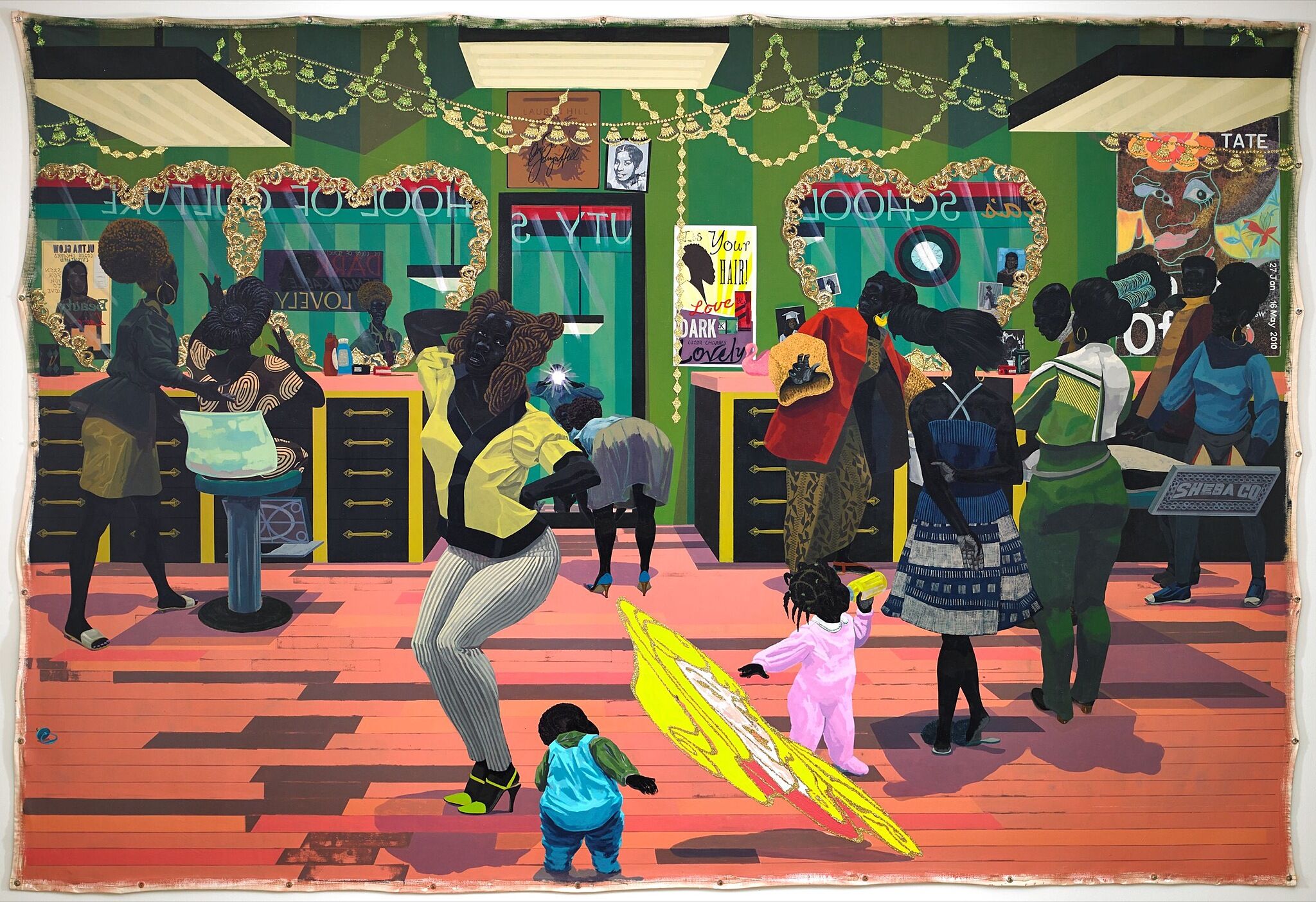

Toor’s strategy of painting Brown men into “the language of the humanities” parallels the work of other contemporary figurative painters, such as Kerry James Marshall and his ambitious, decades-long project of establishing a “counter archive” and marking “the historical absence of black bodies in the Western canon of painting.”“An Argument for Something Else: Dieter Roelstraete in Conversation with Kerry James Marshall, Chicago 2012,” in Kerry James Marshall: Painting and Other Stuff, ed. Nav Haq (Antwerp: Ludion, 2014), 28; Lanka Tattersall, “Black Lives, Matter,” in Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, ed. Helen Molesworth (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2016), 59.Marshall inserts allusions to the Old Masters and to Modernist ones in his paintings of quotidian Black life, and sees his work vis-à-vis the long thread of art history as “an expansion of it, not a critique of it.”Wyatt Mason, “Kerry James Marshall Is Shifting the Color of Art History,” New York Times, October 17, 2016.Toor is also a successor to Nicole Eisenman, who melds everyday contemporary life with art history in her uncanny figurative works that question power dynamics and hierarchies, and to Chitra Ganesh, whose works excavate alternative narratives left out of history, literature, and art to explore representations of femininity, sexuality, and power, and “the body as a site of transgression, both social and psychic, doubled, dismembered, and continually exceeding its limits.”Chitra Ganesh, artist statement. Gayatri Gopinath, “Chitra Ganesh's queer re-visions,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 15:3, Duke University Press, 2009.

Toor’s lush apartment scenes reflect the hybridity of queer Brown men living in liminal, interstitial spaces between geographies and cultures, and the green paintings especially convey this. Toor created his first green painting in early 2019 and deemed it successful, realizing that he could use green to depict “a space of self; for enhancing the self.” He initially reserved the color for nighttime revelry scenes, such as Four Friends (2019) and Bar Boy (2019), in which characters dance and embrace in cramped New York apartments or in LGBTQ bars and safe spaces. Toor has referred to the shades of green he uses, which range from emerald to viridian, as “glamorous,” “poisonous,” “intoxicating,” and “nocturnal,” denoting desire and transgression and representing Babha’s third space, which “enables other positions to emerge” and “gives rise to something different, something new and unrecognizable, a new area of negotiation of meaning and representation.” The third space “displaces the histories that constitute it, and sets up new structures of authority, new political initiatives.”Rutherford and Bhabha, “The Third Space,” 211.

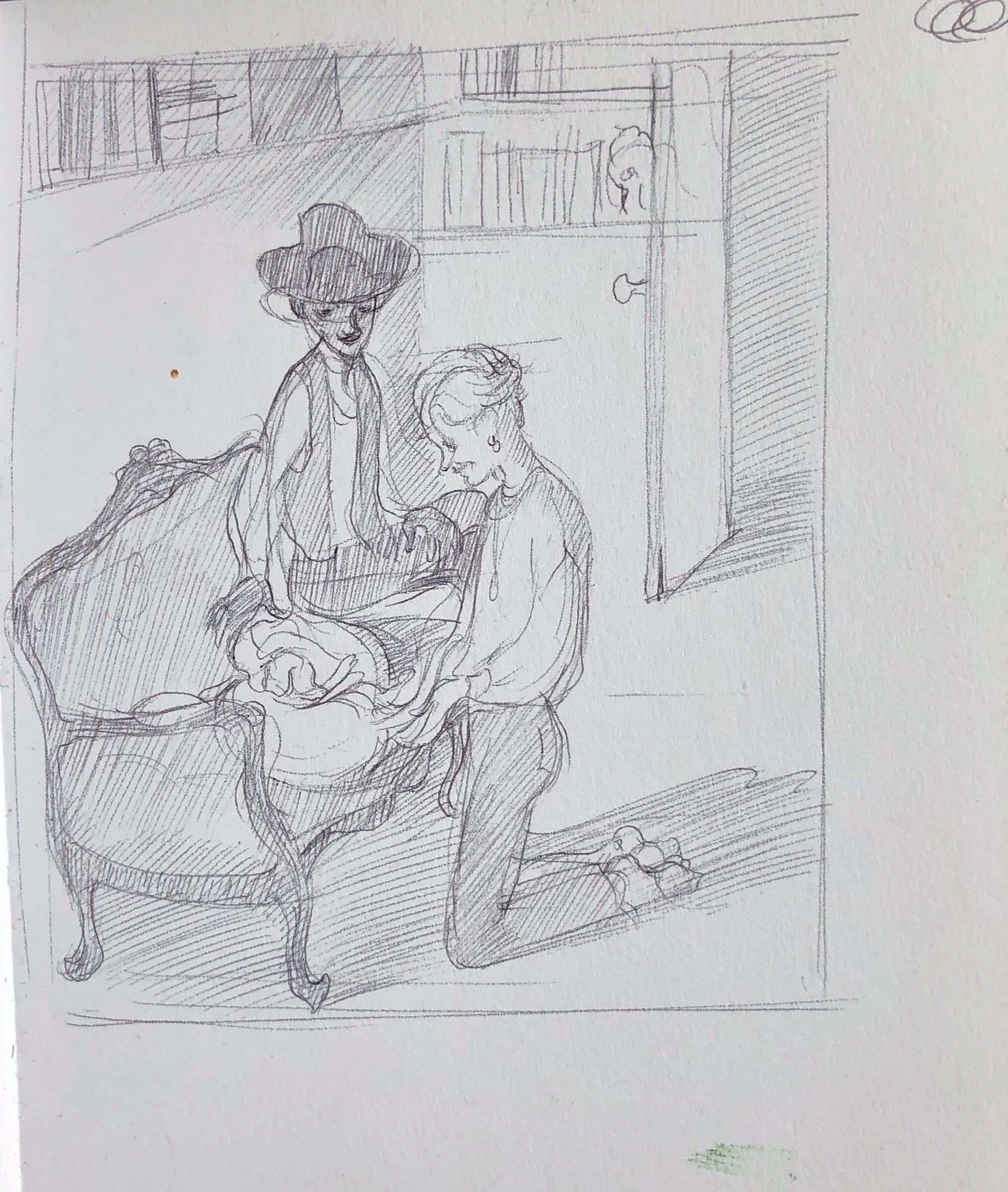

Toor has since expanded his use of green to other vignettes, as in his new painting Tea (2020). The scene, which is reminiscent of The Parable Of The Return Of The Prodigal Son, shows a young man approaching a table that his family is seated around.Many post-Renaissance Dutch Golden Age paintings depict The Parable Of The Return Of The Prodigal Son. Most famous among them is Rembrandt’s The Prodigal Son (c. 1669), while Toor’s Tea perhaps more closely resembles Jan Sanders van Hemessen's The Prodigal Son (1536) or Gerard Van Honthorst’s Merry Company (also titled Prodigal Son) (1622).Only a few elements in the work are not green, notably the young man’s brown hands, hanging limply at his sides, and the father’s hands, holding a cigarette that burns bright orange—perhaps a sign of the tensions in the room. While the actions and emotions remain restrained, the green stands in for what the figures cannot reveal aloud: the dysfunction, difference, and, again, transgression that separate the young man from the rest of his family.

Parts and Things (2019), another green painting, is perhaps the most surreal work in How Will I Know. In it, torsos, legs, heads, and phalluses are piled up on the floor of an open closet, tangled among clothing and a few gold chains. The parts have the curved, rubbery look of limbs in other paintings by Toor, but here they exist independently, dislocated. The work is unsettling and irreverent, suggesting that there are myriad versions of selves one can “try on,” depending on desire or necessity. The painting is also perhaps the closest thing to a self-portrait in the exhibition, as it is an autobiographical examination of Toor’s painterly process and expansive art historical knowledge. His mind, in other words, is a veritable closetful of Raphael hands, Anthony van Dyck noses, Philip Guston legs (and lightbulbs), and Amrita Sher-Gil expressions. “So much of the art history that I love is a pile of limbs,” says Toor. “There’s a poetry to seeing parts of bodies next to each other, in ways they wouldn’t be if they were joined together.”

Parts and Things brings to mind a quote by Alexander Chee, who, in reflecting on his own process of writing an autobiographical novel, calls his characters “ciphers” through which he examines his experiences; his fiction “a prosthetic voice”; and his practice “autonomic . . . as if an invisible creature had moved into a corner of my mind and begun building itself, making visible parts out of things dismantled from my memory, summoned from my imagination.” Chee goes on to note, “I was spelling out a message that would allow me to talk to myself and to others.”Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018), 202, 201.Threaded through the parts in Parts and Things is a feather boa—a seventeenth century garment that resurfaced during the Victorian era, the 1920s, and the 1970s—a common accessory in cabaret and drag performance. A mark of the erotic, its presence queers the “I” in Toor’s painting and extends it beyond any self-imposed limitations or societal constraints. In this third space, “the meaning and symbols of culture have no primordial unity and fixity. . . . The same signs can be appropriated, translated, rehistoricized and read anew.”Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 37.