“Your Hand Is Already Flowing”: Ruth Asawa’s Daily Practice of Drawing

Kim Conaty, Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints

Related exhibition

The exhibition Ruth Asawa Through Line is on view September 16, 2023–January 15, 2024.

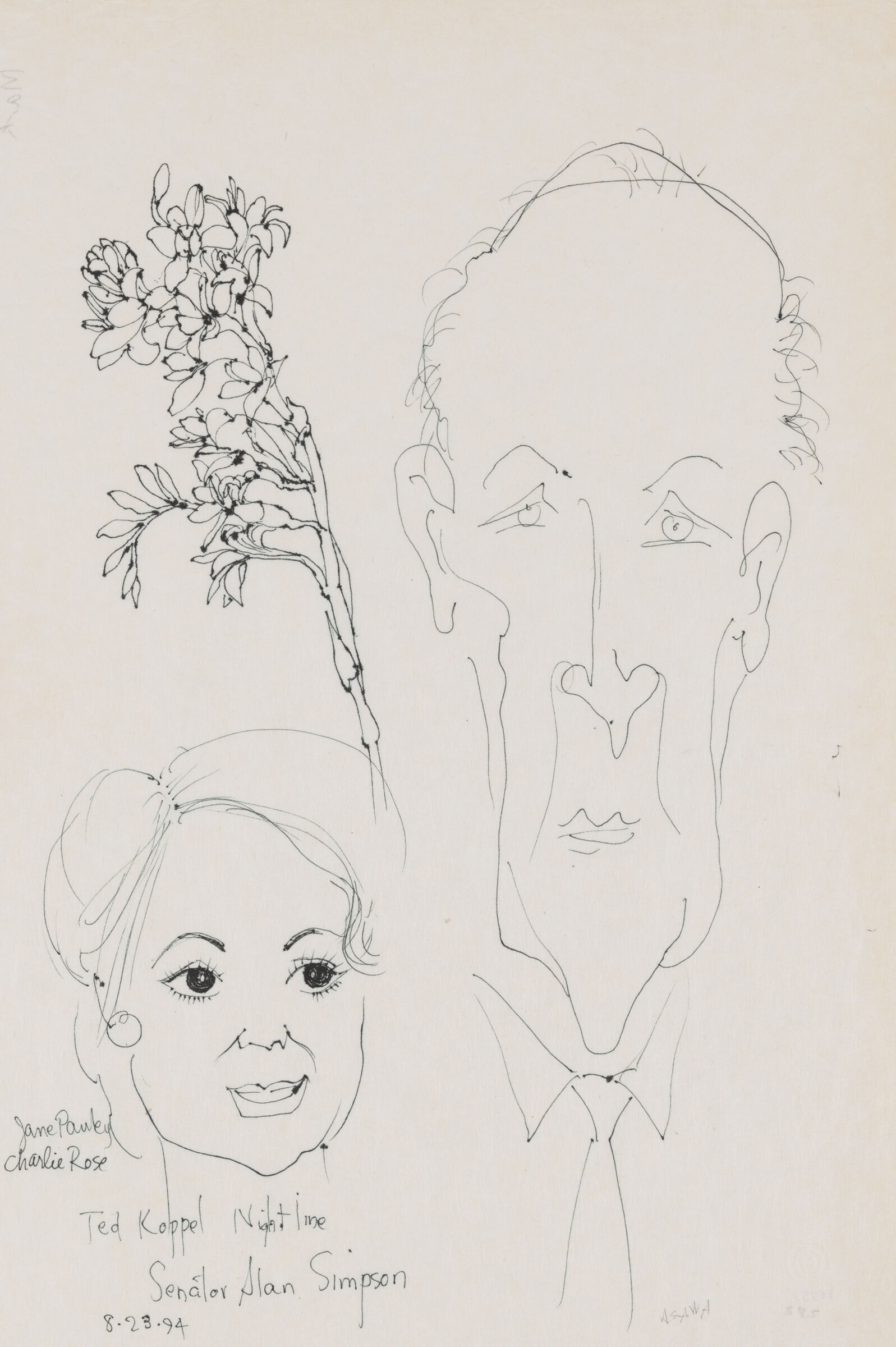

While the world around her slept, Asawa often stayed up, reveling in the open, uninterrupted stretches of time and resting her mind while drawing. She loved to watch her favorite television programs—news station interviews and musical performances, in particular—while capturing the televised subjects in her sketchbooks. As she did in many committee meetings, Asawa participated through the activity of her pen or pencil, sometimes even recording her subjects’ statements alongside their depictions. One sketch from August 23, 1994, depicts television host Jane Pauley from an appearance on the talk show Charlie Rose, alongside a caricatured image of Wyoming Senator Alan Simpson from Nightline with Ted Koppel, and between them an elegant set of intertwined stems and flowers, likely positioned near her as she sketched from the screen.

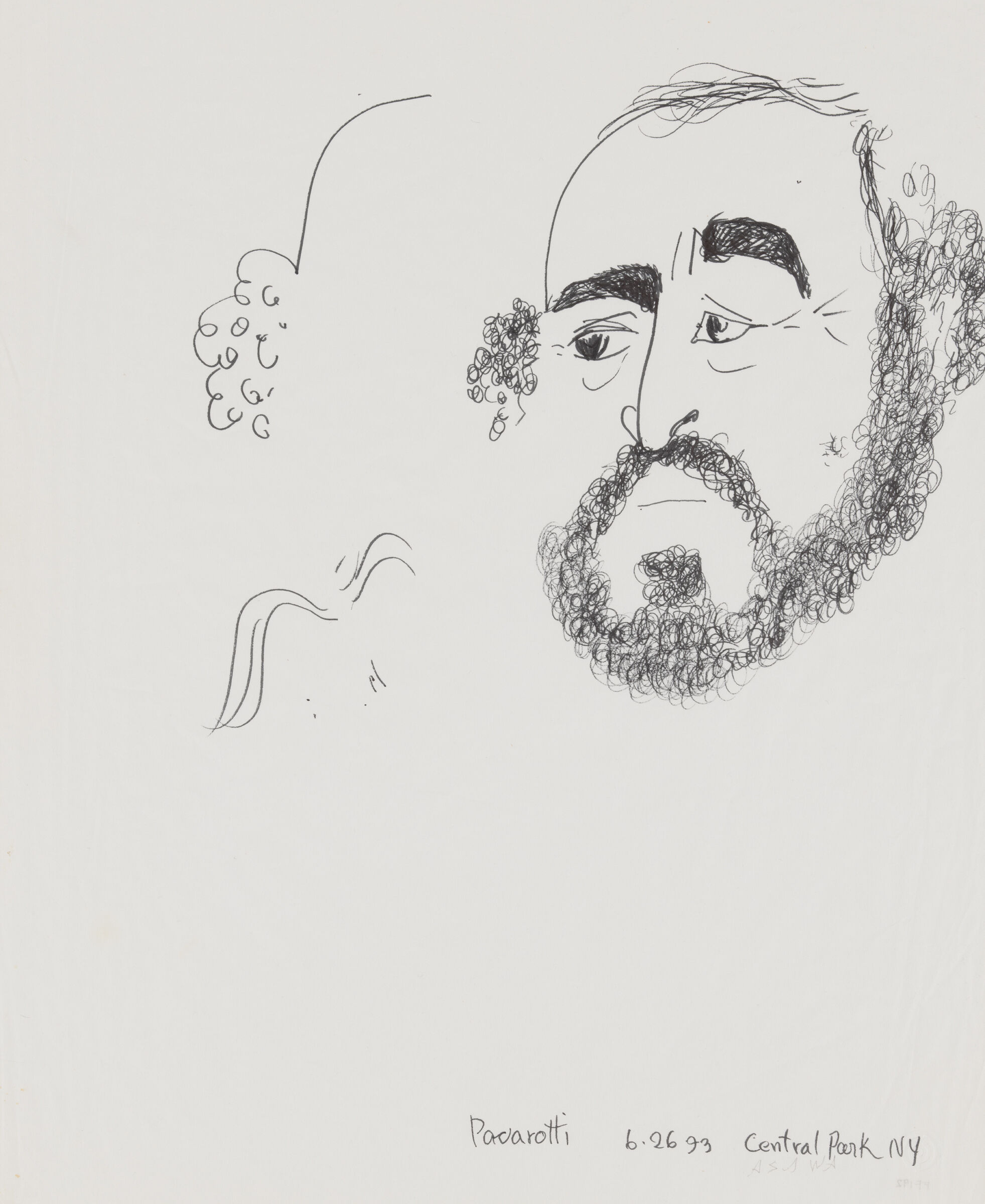

Another, one of many drawings of Luciano Pavarotti—a favorite of hers—captures the expressive facial movement and looping curls of the world-renowned tenor at his June 26, 1993, performance in Central Park, a program broadcast on PBS before millions, all joining this communal experience from their own homes. This was Asawa’s private world, a place where she could take her time to watch, listen, see, feel, and draw.

As part of an autobiographical narrative Asawa began to write in the mid-1980s, she described the ways in which drawing had (or could have) anchored her days: “Ruth washed the dishes, made the bed, and began to draw in her sketchbook. . . . She was happy to draw for hours. . . . She had eight hours to quietly look/study and draw a bouquet of flowers that Albert had picked up at Union Square the day before. . . . Next week it would be a different bouquet. He would find one that he thought she would like to draw.”Ruth Asawa, handwritten pages telling story of her life (her attempts at "fantasy"), March 4, 1985, Ruth Asawa Papers, box 127, folder 5.This story captures the mundanity of a daily practice that is anything but banal; rather, through repetition and over time, “Ruth” opens herself to new experiences, insights, and knowledge. No flower is the same, and every arrangement offers a fresh set of forms to untangle through line. Without voices of their own, these subjects relied on Asawa moving her eye ahead of the pencil, watching them with an unwavering gaze while she worked rather than looking down at the movements of her line.

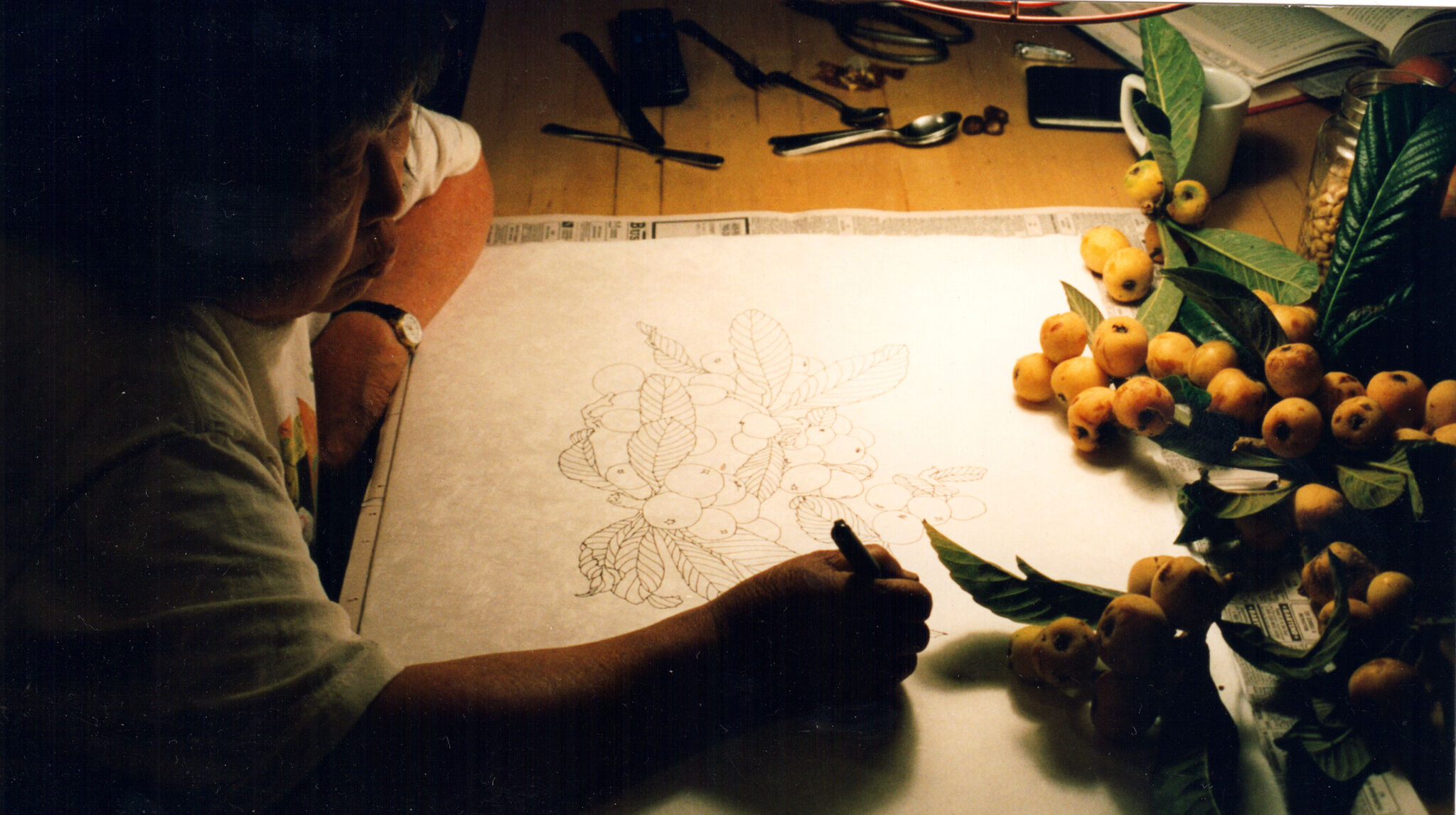

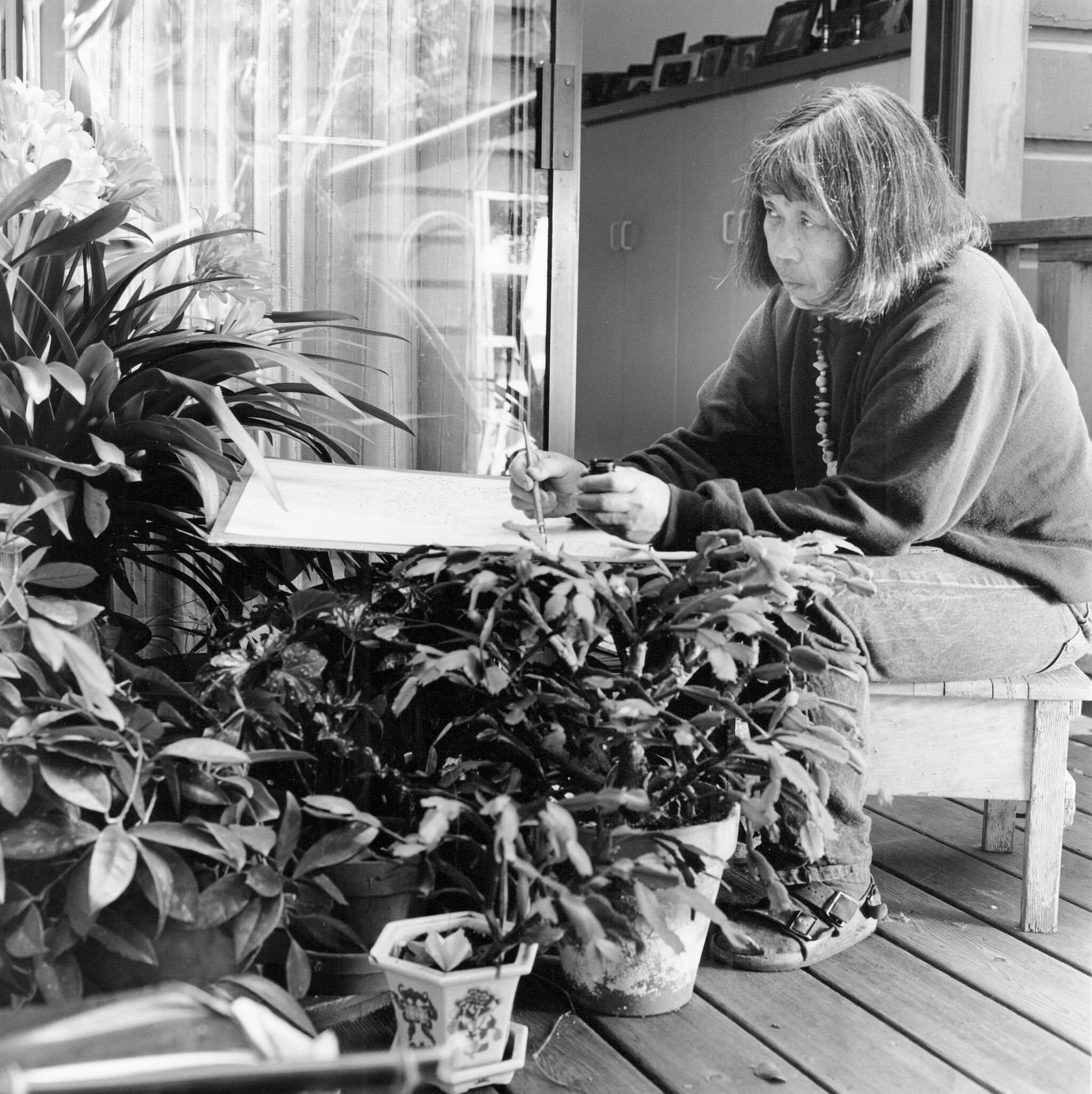

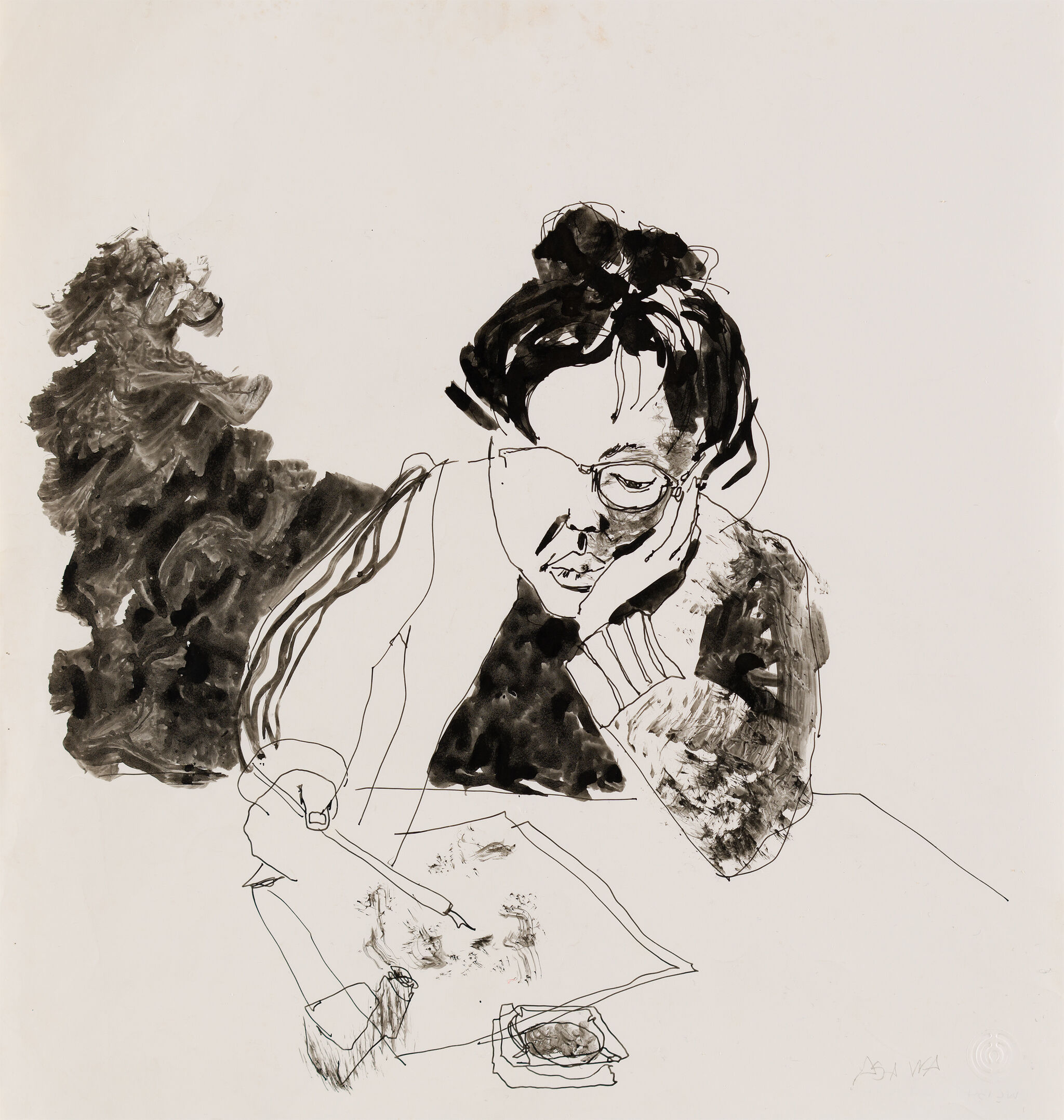

Captured in a 1990 photograph sketching the plants on the patio outside her house, Asawa appears to be fully absorbed in the act of looking, her body leaned in to her work, elbows resting comfortably on her knees, and chin tilted up just enough to take in the jungle of leaves, stems, and petals before her. As if extensions of her engaged body, her nib pen rests comfortably in her right hand, which hovers over the paper, the ink pot settles in her left. Whether studying plant forms in her garden or staying up late into the night sketching loquat cuttings at her table, Asawa’s solitary drawing practice was a critical, grounding part of her days that most people did not see. Portrayed so often by her mother while growing up, Aiko (Cuneo) turned the lens back on her mother in a photographic nocturne that captures Asawa’s relentless energy and perpetual insomniaAsawa's perpetual insomnia has been discussed often by her family. Recent publications that have cited this include Ruth Erickson, "Wide Awake," in Ruth Asawa: All Is Possible, Helen Molesworth et al. (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2022), 30.(see the first image on this page).

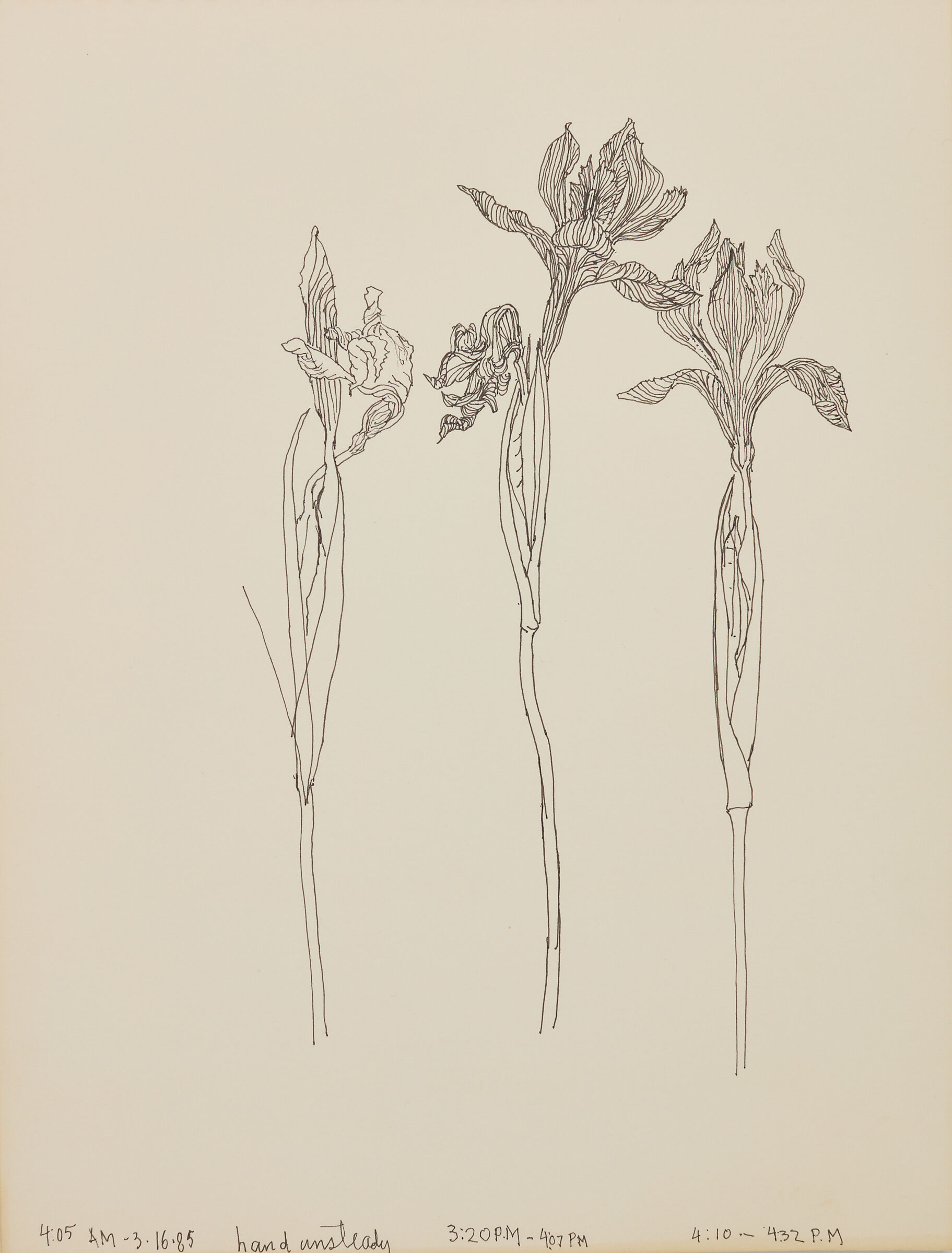

Throughout Ruth Asawa’s life, her line served as a sustaining force and, at times, a barometer. A notebook page from a debilitating bout with lupus is a testament to drawing’s continued role as salvation. Three irises, sketched on a single page and annotated with the time of day in which she made them, mark her convalescence. The strokes of her pen forge the graceful, arcing stems that open and expand into lines and waves. With “hand unsteady,” she continued to draw, exercising eye, mind, and body in a record and reflection of her well-being. Drawing, always, was the through line.

This is an excerpt from Kim Conaty's essay “‘Your Hand Is Already Flowing’: Ruth Asawa’s Daily Practice of Drawing.” Read the full essay in the exhibition catalogue Ruth Asawa Through Line.

Not all of the artworks referenced in this essay are included in the Whitney Museum’s presentation of Ruth Asawa Through Line.