New Instruments: A Search for Silent Signals

Madeline Hollander’s choreographic practice, which fluidly encompasses dance, video, installation, drawing, and sculpture, is rooted in an investigation of movement-based responses to environmental and social crisis. Inspired by the accelerating changes that characterize our present—and the urgent task of responding to them—Hollander’s works span the microcosmic scale of individual routine and the macrocosmic one of societal protocol. In her immersive video installation Flatwing (2019), she searches for flatwings, a newly emergent population of silent crickets, as a case study for the difficulties of adaptation across species and disciplines. The flatwings, who are stuck silently performing the same mating ritual that crickets evolved millions of years ago, now teeter between adaptation and extinction. For Hollander, a choreographer interested in the meaning revealed by routine gestures, their mute movements represent our own struggle to shift entrenched habits.

While making the work, she wrote the following list:

How the leopard got its spots

How the zebra got its stripes

How the camel got its hump

How the snake got its tongue

How the crickets got their dance

How the sun got its hum

Hollander’s entire body of work is concerned with the morphologies and innate movements that have evolved slowly over time, and especially those that are now threatened by unpredictable ecological change—the leopard’s spots, the zebra’s stripes, and, in the case of Flatwing, the cricket’s chirp. She closely scrutinizes the warning communicated via the crickets’ silenced call, looking at what it can reveal about the adaptability of our routines under conditions of increasing precarity.

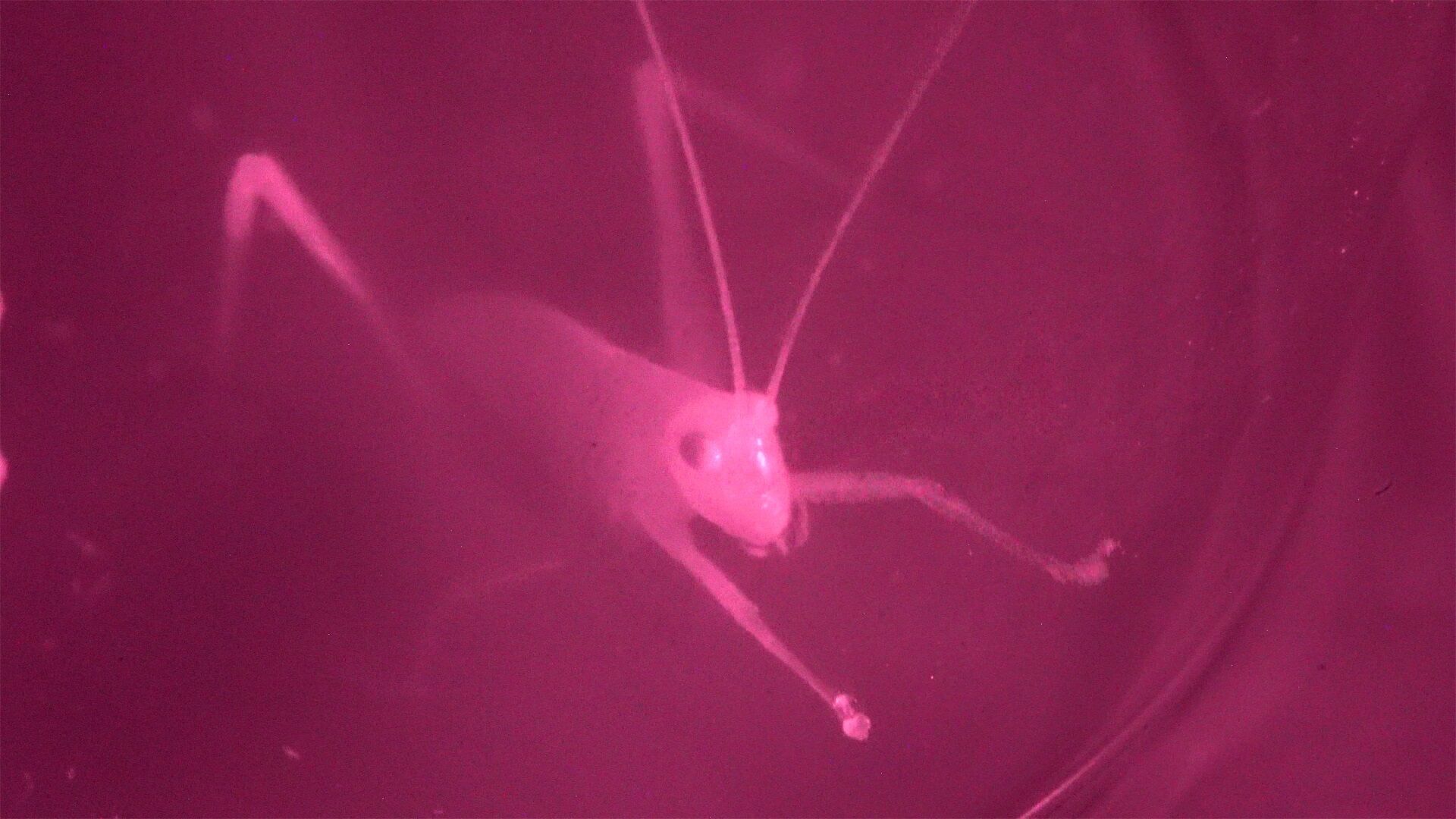

Flatwing takes viewers on an enveloping, disorienting search for silent Polynesian field crickets, following Hollander’s journey across a nightscape as she looks in vain for a subject that never actually appears on-screen. Hollander traveled to the Hawaiian island of Kauai with the goal of filming the insects as movement research for the performance New Max (2018), which she was at the time developing. Over the last fifteen years, silent cricket populations have rapidly emerged on a few islands in Hawaii, including Kauai, where they now comprise the vast majority. As a result of a genetic mutation, these crickets lack the wing ridges that normal male crickets use to create their chirping mating calls. In most contexts, this development would place the flatwings at a reproductive disadvantage. In this case, however, their silence enables them to elude a species of parasitic fly that has decimated chirping cricket populations on the islands, so that in only a handful of years, the flatwings have come to make up the majority of the population.The Polynesian field cricket, Teleogryllus oceanicus, is an invasive species in these Hawaiian islands. Such rapid evolutionary change demonstrated by the flatwings often occurs when organisms are introduced to new environments because their sexual signals either do not perform well or attract different predators. In this case, the crickets coexist with Ormia ochracea parasitic flies, which are rapidly decimating the chirping populations, locating them with their excellent hearing and then laying eggs on the crickets’ back. Flatwing populations were negligible in the late 1990s and 91 percent of the population by 2004. For more information, see R. M. Tinghitella, “Rapid Evolutionary Change in a Sexual Signal: Genetic Control of the Mutation ‘Flatwing’ That Renders Male Field Crickets (Teleogryllus oceanicus) Mute,” Heredity 100 (2008): 261–67.So far, the flatwings have been able to reproduce through “satellite mating”: they surround the remaining chirping crickets and then intercept the summoned females, all the while reflexively going through their wing motions without actually producing chirps. Their silence serves as a protective invisibility cloak against the species’ enemy, but it may also prove fatal to the population overall. When all the chirping crickets have been killed, the flatwings will no longer be able to summon their mates, and the population is likely to go locally extinct.

To observe the noiseless crickets in the wild, Hollander would, ironically, depend on listening, hoping to locate them through the chirps of the few remaining ones with ridged wings. With most of the crickets on Kauai already silent, she knew that the mission was unpromising from the start, which gives Flatwing a tragicomic cast.M. Zuk, J. T. Rotenberry, and R. M. Tinghitella, “Silent Night: Adaptive Disappearance of a Sexual Signal in a Parasitized Population of Field Crickets,” Biology Letters 2, no. 4 (2006): 521–24.Equipped with an infrared video camera, a regular video camera, a boom mic and field recorder, a wheelbarrow containing an infrared lamp soldered to a car battery, a headlamp, and a tarp that she used to protect this assemblage from rain, she followed her ears through the rainforest, listening through the microphone for the chirps of the crickets whose silent siblings she hoped to find. In Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, poet and scholar Alexis Pauline Gumbs proposes that studying echolocation, used by marine mammals to navigate the world through the bouncing of sound underwater, may expand our understanding of vision.Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2020), 15.In relying on the insects’ own primary way of communicating and using sound as her guide, Hollander makes a similar attempt. Gumbs writes, “How can we listen across species, across extinction, across harm?”Ibid.During her nighttime treks, Hollander encountered katydids, other insects, chickens, and frogs, but no crickets. Flatwing, the work that she made from the footage filmed on her journey, is a product of her listening both literally, to the sounds of the rainforest, and metaphorically, to the alarm that she identifies in the rapid silencing of the crickets’ song.

In Flatwing, she speaks with evolutionary biologist Marlene Zuk, an expert on the flatwings whom she contacted before journeying to Kauai. In their conversations, which appear throughout the video’s soundtrack, the artist and the scientist talk past one another. Approaching the crickets as a choreographer, Hollander scrutinizes movements that are not of interest to an evolutionary biologist. Zuk explains that any differences in motion between the flatwings and the normal crickets would be imperceptible, but Hollander continues to inquire about them. As each party reverts to the conventions of her respective discipline, the resulting miscommunications reinforce a concept woven throughout Hollander’s entire artistic practice: we are stuck in our habits. “It’s important to appreciate how different other organisms are from us,” Zuk tells Hollander. “If you were that size and were down there, you would try and see, you would try and do all [sorts of] things. They are not like people.”Hollander also challenges some of Zuk’s assumptions. The scientist suggests that she should film the crickets in the lab, where they are isolated and easy to observe, rather than trying to do so in the field. “There is no reason to do it in the field,” she tells Hollander, who replies, “Except for the natural landscape. It would be an infrared so it would be at night.” For Hollander, the goal is to record the crickets in their natural habitat rather than in the isolated conditions of the scientific lab, for both conceptual and aesthetic purposes. For Zuk, quantitative recorded data on the crickets’ mating or locomotive behavior is much more useful than this video footage.The scientist misunderstands. Hollander isn’t anthropomorphizing the silent crickets. Rather, she is interested in how their reflexive chirping motions are analogous to our own futile reflexive behaviors.

Hollander’s projects rely on intensive research about natural and manmade systems such as flood mitigation, temperature control, and concrete production, and she closely consults professionals from the field at hand. Typically, the investigative process takes place behind the scenes, but in Flatwing, she makes it the subject of the finished work. More usual is Heads/Tails (2020), in which Hollander installed hundreds of recycled automobile headlights and taillights at New York’s Bortolami gallery, individually programmed to light up according to typical New York City drivers’ behavior patterns and collectively synced to the traffic signal at a nearby intersection. To create the piece, she sat at a road crossing and recorded the timing of different motorists, then used this field research to develop scores based on fictionalized personality types she had observed. She also researched current and historical New York City traffic management, eventually working with the city’s Department of Transportation to tap into the live information stream that coordinates the city’s traffic lights. Her interest in this data—which gathers inputs that include weather, accidents, school times, bus routes, holidays, foot traffic, and more—reflects her conception of choreography as the flows of beings and information that comprise our daily life.

With the choreography Hollander had hoped to create having proved impossible, she took a different approach: in Flatwing, she exposes her mode of inquiry, making it central to the work in order to reflect on the norms of scientific research. In ways, her search adheres to scientific methodologies—she looks for evidence to support her hypotheses about the crickets, for example—but it is outside the paradigm of science. For some, her self-described “choreography through the jungle” may exist beyond a conventional understanding of dance. In order for anything to be legible within its field, it must make reference to certain conventions while expanding others. Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn proposed that our colloquial understanding of discovery misleadingly suggests “that discovering something is a simple act assimilable to our usual (and also questionable) concept of seeing.” In fact, the discovery of a phenomenon is a complex, embedded event that involves “recognizing both that something is and what it is.”Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 55.In other words, any scientific discovery requires the prior existence of a framework in which that discovery can be identified and named.

For Kuhn, since every paradigm is inherently flawed and incomplete, scientific work necessarily raises anomalies. As they accumulate, they lead to periods of crisis and to the development of a new prevailing paradigm.Ibid., 103.Hollander’s work is concerned with such accruing piles of irregularities, and she often isolates a specific movement-based peculiarity as a synecdoche for the transforming social and natural systems in which it is enacted. In her ongoing Gesture Archive (2012–) video project, for instance, she catalogues rote movements that are becoming obsolete with increasing frequency, such as the gesture of making a phone call taking the shape of the thumb and pinkie finger held up to one’s head like the handset of a landline phone. Flatwing builds on this interest, documenting her investigation into an insect performing a nonfunctional mating gesture that will soon likely vanish. For Hollander, the flatwings’ “pantomime” is a vestigial choreography that the insects continue to perform even though it no longer fulfills its purpose. “It is the speed, the speedboats, the momentum of capitalism, the expediency of pollution that threatens the ocean, our marine mammal mentors, and our own lives,” writes Gumbs.Gumbs, Undrowned, 141.Hollander’s body of work is rooted in a fascination with this speed of change; she speculates that vestigial gestures may become ever more ubiquitous as societal changes accelerate. The futility of the crickets’ chirping motions serve as a harbinger for our own inability to adapt.

Meanwhile, as natural environments face unprecedented change—accelerating carbon emissions, rising temperatures, high rates of species extinction—prevailing assumptions within scientific disciplines do not always hold. Reports on the need to rapidly adjust scientific paradigms in the face of the earth’s rapidly changing climate proliferate; to cite one paper, “A paradigm shift enabling greater attention to climate-targeted approaches is likely to be needed as climate change accelerates.”Suzanne Prober, Veronica Doerr, Linda Broadhurst, Kristen Williams, and Fiona Dickson, “Shifting the Conservation Paradigm: A Synthesis of Options for Renovating Nature under Climate Change,” Ecological Monographs 89, no. 1 (2018).We are conventionally taught that evolution is a slow process that unfolds over hundreds of decades, yet the crickets on Kauai have rapidly evolved and may just as rapidly disappear. Neocatastrophism, which is “mostly nowadays regarded as standard geology,” according to environmental writer Elizabeth Kolbert, explains how drastic changes characterize our moment, proposing that “conditions on earth change only very slowly, except when they don’t.”Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2014), 94.Zuk and her colleagues are confronted with the difficult task of continuing to generate discoveries—the genetic origin of the wing mutation, the locomotive behavior of the flatwings, the connection between the flies and the crickets—while also adjusting to more fundamental and disruptive shifts.

In Flatwing, Hollander wonders while talking to Zuk whether the silent crickets might figure out a new way to mate even after the chirping crickets disappear, through “some sort of replacement to that call in the form of a dance.” Again, Zuk counters, replying that she thinks that if the normal crickets disappear, “the whole shebang is going to go extinct and the populations will stop existing.” It was after reading a study published by Zuk indicating that the flatwing crickets are more locomotive than their chirping counterparts that Hollander determined to document this behavior.S. L. Balenger and M. Zuk, “Roaming Romeos: Male Crickets Evolving in Silence Show Increased Locomotory Behaviours,” Animal Behaviour 101 (2015): 213–19.She knew, however, that she was unlikely to find the insects; in her notes on the work, she describes the whole endeavor as Don Quixote-esque. Flatwing falls into a category of Hollander’s work that she calls Soundset, an umbrella concept for projects that offer such movement-based solutions for adaptation or communication through rapidly shifting conditions. The notion of the Soundset is based on an open-ended science fiction story that the artist began writing in 2012, in which a reaction between the atmosphere and the sun’s light waves results in a type of "climate synesthesia,” producing a tone whose frequencies increase according to the intensity of the light. During the day, the sound drowns out all other sounds, necessitating communication through “a new corporeal vocabulary.”Madeline Hollander, “Soundset” (master of fine arts thesis, Bard College, 2018).

As Flatwing progresses, the film captures an increasing sense of hopelessness. Hollander follows false start after false start. She mutters to herself. The score, including an original composition by her sister, Celia Hollander, captures the competing, misleading rainforest sounds guiding Hollander’s journey, imbuing them with an increasingly foreboding quality. Hollander filmed across five nights, then edited the piece chronologically through the passage of evening (so that, for example, footage from eight pm appears toward the beginning and footage from midnight appears toward the end). In the humid, rainy climate, water droplets progressively accumulated on the lens as each night went along, appearing in the footage like a constellation of blurry stars. Her own failed trek through the rainforest evokes how difficult it would be for the silent crickets to find mates without their song: they can’t see through the darkness and neither can we.

Flatwing opens with a conversion printed in pink letters on a black background: “To calculate the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit, count the number of chirps in fourteen seconds and add forty.”For example, if you hear thirteen chirps, the temperature is 53 degrees Fahrenheit. If you hear twenty chirps, it is 60 degrees Fahrenheit. If you hear zero chirps, it is below 40 degrees, as crickets cannot chirp in the cold.Published by Amos Dolbear in 1897, this formula reveals a point of intersection in the rhythms of seemingly disparate natural systems: the weather and cricket mating calls.A. E. Dolbear, “The Cricket as a Thermometer,” American Naturalist 31, no. 371 (1897).Crickets are cold blooded; their body temperatures match that of their environment, resulting in a direct correlation between the speed at which their wings can vibrate and the ambient temperature. They are natural thermometers. In publishing his law, Dolbear observed, “At night when great numbers are chirping the regularity is astonishing, for one may hear all the crickets in a field chirping synchronously, keeping time as if led by the wand of a conductor.”Dolbear, “The Cricket as a Thermometer.”

Hollander was struck by the resonant coincidence that these temperature keepers are going silent on Kauai as our planet’s temperatures also go out of sync. The infrared camera, the tool that she uses to look for and film the crickets is itself, in a sense, a specialized instrument for measuring temperature, the process that crickets do according to their biological design. In the video, the trees, foliage, insects, and animals that Hollander encounters are translated by her infrared camera into glowing, mesmerizing shades of purple, pink, and red whose brightness corresponds to the object’s temperature. In the installation at the Whitney, this nightscape is projected at a larger-than-life scale, and the moving images reflect in the shiny painted floor of the room, dematerializing the space and causing its physical structures to disappear. The installation thus immerses its viewers in the disorienting, technologically mediated, pink-hued world that Hollander experienced for the five nights that she searched for crickets in the rainforest.

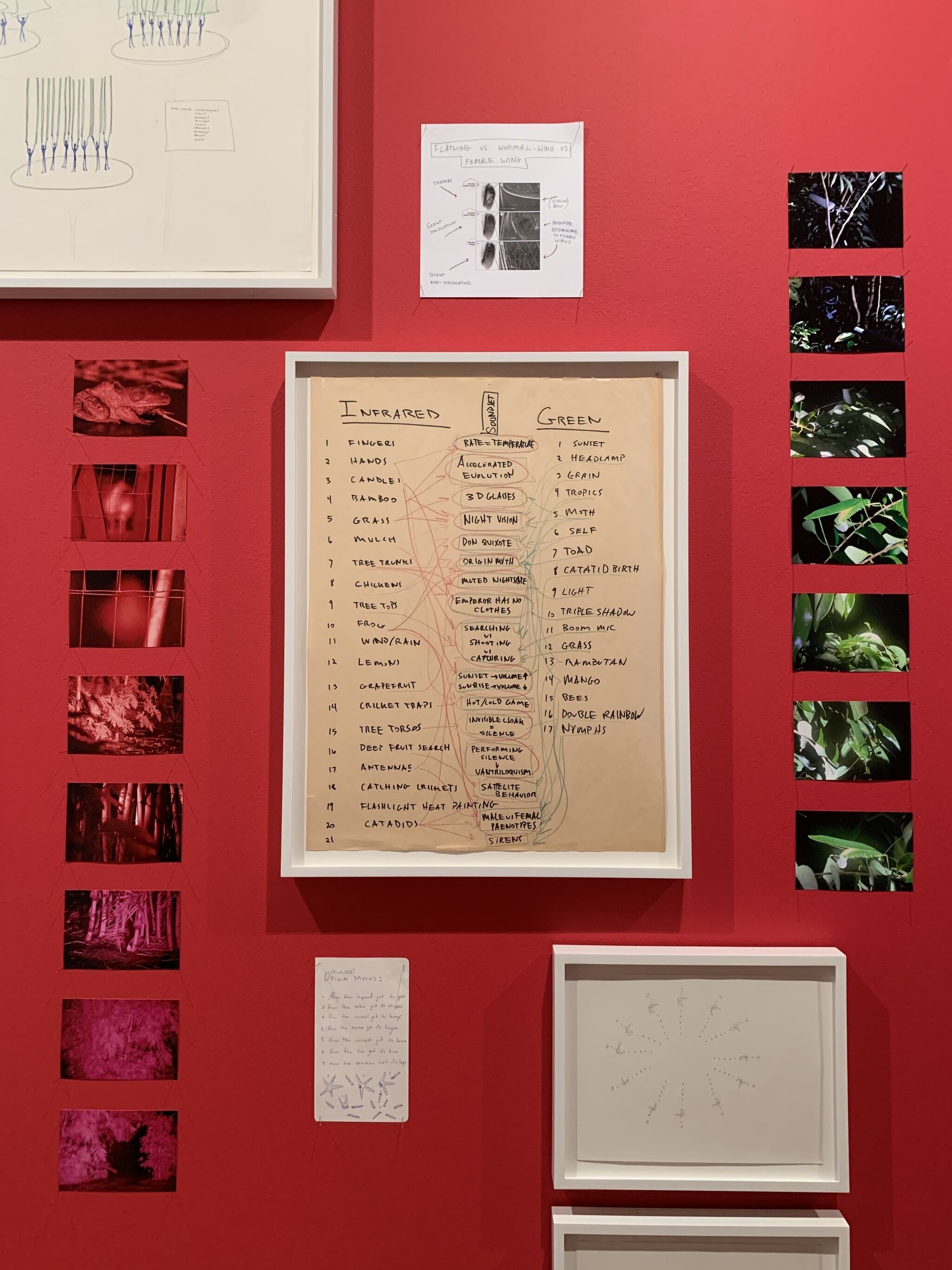

As viewers leave the red-tinted space in which the film is projected, their eyes naturally compensate for the shift by a heightened perception of the color green. Hollander has enhanced this effect even further in the adjacent gallery by placing a green filter over the window. The color environments of these galleries mirror Hollander’s own optical experience through the rainforest: red through the infrared camera and a dark, nighttime green through her own eyes, a normal camera, and an iPhone. In the space leading to the video installation, the diagrams, drawings, and research materials that Hollander created and consulted in the process of creating Flatwing are on display. While specific to this work, the diagrams enumerate and reveal points of connection between concepts that underpin her entire body of work. One of these divides the red and green footage that she captured in Kauai according to their subject matter, such as “chickens,” “grass,” and “hands,” and links each to related concepts that include accelerated evolution, night vision, and Don Quixote. Also on view are a number of drawings that demonstrate her unique system of color codes and pictographs to record movement sequences, which eschew the widely used Labanotation system. In describing her notation, Hollander has said, “The drawings are only meant to be understood by me and the dancers. It’s a system for recall. To remind the bodies who already lived through the movements.”“Studio Visit: Madeline Hollander by Mikkel Rosengaard,” Bomb, September 21, 2018.

In the adjacent Goergen Gallery, Hollander has also installed a new sound work, for which the tempo of cricket chirps corresponds to live data of the local outside temperature.Visitors, who directly experienced the outside temperature before entering the museum, then hear a sonic translation of it in the tempo of the cricket chirps, which have been scored by Celia Hollander.The formula for Dolbear’s Law is silkscreened on the wall. This work, like the red and green color environments of the two rooms, is part of Hollander’s effort to engage viewers of all her works as embodied subjects.The global coronavirus pandemic, which occurred during the preparations for this exhibition, has also resulted in an increased monitoring of personal temperature. In advance of all on-site meetings at the museum, the exhibition team and artist had their temperatures recorded. During the run of the exhibition, museum staff will also take the temperature of every visitor upon their entrance to the museum.In New Max, the performance at the Artist’s Institute in New York for which Hollander began her cricket research, dancers performed warming-related movement sequences in conjunction with air-conditioning units, working to raise and lower the temperature of the exhibition space. Viewers thus had both a visual and a directly corporeal experience of the duet between dancer and machine, which raised and lowered the room’s temperature to incrementally increasing levels between sixty-five and eighty-five degrees.“Madeline Hollander: Temperature,” The Artist’s Institute official website. The duet between human and machine developed in New Max also relates to Arena (2017), a performance that Hollander staged at Rockaway Beach, New York. In that work, dancers and beach-rake trucks performed in a continuous loop: the former created markings in the sand with their footprints and the latter erased them.The audience was directly involved in the pas de deux, acting as a warming body alongside the dancers.

Hollander’s work is rooted in a dance lineage drawing from functional everyday movements that has unfolded over the last half century. In a 1965 interview, founder of the San Francisco Dancers' Workshop Anna Halprin explained to her former student Yvonne Rainer that “doing a task created an attitude that would bring the movement quality into another kind of reality,” as the movement is then “devoid of a certain kind of introspection.”“Yvonne Rainer Interviews Ann Halprin,” Tulane Drama Review 10, no. 2 (1965): 147.For Halprin’s The Bath (1966–67), for example, she and her dancers created movement sequences based on the daily task of bathing. Hollander works likewise; Marielis Garcia, one of the dancers in her work for the 2019 Whitney Biennial, Ouroboros: Gs, notes, “The choreography is always task first. How do I best approach the task using this movement.”Siobhan Burke, “At the Whitney Biennial, Flood Preparation as Social Dance,” New York Times, September 17, 2019.Halprin, Rainer, and their peers marked a radical shift in dance, turning away from plot- or spectacle-based movement to pedestrian gestures. In the statement for her 1968 performance of The Mind Is a Muscle at the Anderson Theater in New York, Rainer wrote: “It is my overall concern to reveal people as they are engaged in various kinds of activities—alone, with each other, with objects—and to weight the quality of the human body toward that of objects and away from the super-stylization of the dancer.”The Mind Is a Muscle program statement, Anderson Theater, New York, 1968. Reproduced in Catherine Wood, The Mind Is a Muscle: Yvonne Rainer (London: Afterall Books, 2007), 41.Hollander’s dances, which often comprise natural or systems-based movement sequences, extend the lexicon of ordinary movements formulated by these two pivotal artists as well as the Judson Dance Theater, in which Rainer played a key role.

Hollander also draws on philosophical inspiration in focusing on the discrete movement sequences and gestures that she isolates and suspends. In a 1931 essay on Bertolt Brecht’s Epic Theater, Walter Benjamin writes about gesture, which he describes as the interruption of an action. For Benjamin, this freezing of gesture produces a state of “dialectics at a standstill,” in which the “social conditions, situations, or states” that inform those gestures can be scrutinized.Lucia Ruprecht, “Gesture, Interruption, Vibration: Rethinking Early Twentieth-Century Gestural Theory and Practice in Walter Benjamin, Rudolf von Laban, and Mary Wigman,” Dance Research Journal 47, no. 2 (2015): 26.Building on this writing, Theodor Adorno proposes that “to experience art means to become conscious of its immanent process as an instant at a standstill.”Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (New York: Continuum, 2002), 84.In other words, the experience of an artwork necessarily involves an awareness that the work was made in the conditions of a specific time and place. Hollander homes in on routine movements to understand what they reveal about the conditions in which they have been made, present or past, and the circumstances in which they were once functional. In seeking to record the motions of the flatwings before they go extinct, her practice reflects that “artworks are the persistence of the transient.”Ibid.

Hollander’s interest in gesture also looks toward the future. In Ouroboros: Gs, she created a site-specific performance based on the installation of part of the museum’s advanced flood-protection wall. The performance captures the gestures that routinize crisis management, divorced from the urgent conditions in which these movements might otherwise take place. When putting up a flood wall becomes a performance rather than a crucial, time-sensitive procedure, we shift our own expectations about climate preparedness and perhaps shift our recalcitrant habits of body and mind. Natural processes that regulate atmospheric carbon levels cannot keep up with our levels of pollution. Meanwhile, some corporations try to justify continued pollution through the long-shot promise of technologies that propose to sequester carbon despite their potential environmental and social costs.A recent New York Times article explains that large corporations are investing in potential technologies to pull and trap carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, justifying their current pollution via the uncertain promise of future technology.The threats posed by continued greenhouse gas emissions are urgent, relying on dramatic cuts and proactive shifts to how we live and consume. Hollander’s choreographies ask their viewers and participants to recognize the reality of climate change and consider their habits and norms within that framework.

The ability to dance—to create premeditated motion imbued with meaning—differentiates us from the crickets, with their genetically programmed reflexes. In Techniques of the Body, anthropologist Marcel Mauss explains that when we look at our habits, “we should see the techniques and work of collective and individual practical reason rather than, in the ordinary way, merely the soul and its repetitive faculties.”Marcel Mauss, “Techniques of the Body” (1935), trans. Ben Brewster, Economy and Society 2, no. 1 (1973): 73.In other words, our habits are not innate. They are shaped by individual and structural forces. We face profound existential threats that necessitate dramatic shifts in human behavior. And yet we continue to ignore the flatwings’ silent alarm.