Samples of Everyday History in Ken Ohara’s CONTACTS

Samples of Everyday History in Ken Ohara’s CONTACTS

Throughout the exhibition planning process, Ken Ohara (b. 1942) repeatedly tells me: “You are the curator.” He says this to indicate that he does not want to situate the meaning of CONTACTS (1974–76) in a prescribed path that traces a direct route from artist to object to audience. “It’s not that I’m refusing to share,” Ohara gently elaborates, “[but] if I explain my way, then the viewer is going to have a limited understanding about it. If I don’t say, they’ll try to understand, and the work can get bigger.” Having his work “get bigger” in a physical sense is one of the main objectives of Ohara’s use of repetition and accumulation in his photographic works.

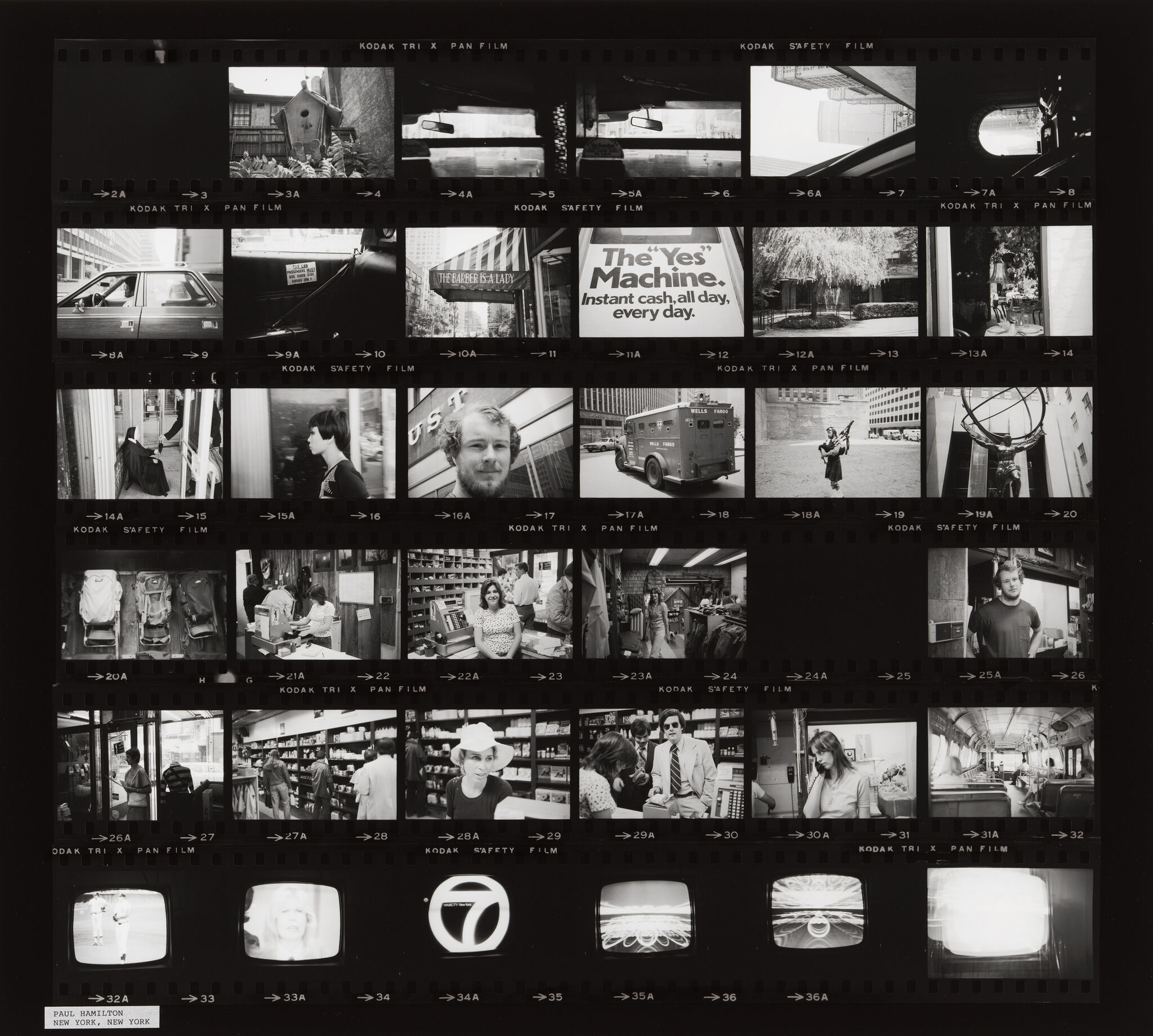

CONTACTS began in 1974 when Ohara mailed his Olympus 35 RC camera, pre-loaded with 35mm film, to a stranger he randomly selected from the Manhattan telephone book. Along with his camera, Ohara sent instructions that directed the recipient to photograph themselves and their family and friends and then return the camera to him along with the name and address of the next person he should send it to. Funded by a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship, the project unfolded over two years, with Ohara’s camera landing in the hands of one hundred different participants across the country. The final work is made up of the resulting one hundred enlarged contact sheets.Ohara worked with the Japanese printer Shashin Kosha, Inc., to print the enlarged sheets.

CONTACTS was preceded by Ohara’s first photo book, ONE (1970), which includes over five hundred close-up, cropped portraits of strangers he photographed in Manhattan. His work Self-Portrait 365 (1970) built on the accumulative and serial structure of ONE while adding a bounded temporality to this method of repetitive image making. Self-Portrait 365 documents a year, with each day represented by two photographs: an inward view (usually a self-portrait of the artist) and an outward view (cityscapes, portraits, and shots of his West Village apartment).Ohara restarted Self-Portrait 365 in 2000 and continued it until 2023. The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently acquired both the 1970 iteration and twenty-three iterations created in the twenty-first century. The work’s material form—a forty-six-foot-long accordion book—contains time in a dense, snaking shape that presages the linear, chain mail structure of CONTACTS.

The sets of rules and procedures that give shape to Ohara’s photo projects from the early 1970s stem from his belief that things will happen through repetition and accumulation. In the case of CONTACTS, Ohara trusted that something would emerge from the one hundred rolls of film, that perhaps the unexpected might be best found in the continuous material of everyday life. When Ohara says that he wants the work to get bigger in meaning as well as in size, I am struck by the feeling of being the next person in the line of strangers that make up CONTACTS—as if he is now handing the camera over and asking me to make something with it. Soon after Ohara moved to New York City from Tokyo in 1962, he sat on the floor of a Soho loft watching the dancer Yvonne Rainer perform. Her movements were surprising in their simplicity: she bent over, fell to her knees, got up, walked around. “It shocked me,” Ohara recalls, “something opened up.” Rainer’s ordinary, everyday gestures—made strange by the weight of attention given to them—unlocked a sense of artistic possibility for Ohara. He remembers wondering: What did this mean for photography? How might one create a photography of the ordinary made unexpected?

Many artists working in the sixties and seventies turned to the camera as a tool for experimenting with the substance of ordinary life. CONTACTS finds particular resonance with Robert Frank’s photobook The Americans (published in France in 1958 and in the US in 1959). Although very different in execution and outcome, Frank and Ohara both created complex portraits of a vast country through the accumulation of snapshots that unfold across time and space at a set rhythm—Frank’s at the speed of the car he drove and Ohara’s at the pace of the camera changing hands.

The 1967 Museum of Modern Art exhibition New Documents further established photography as a tool for observation rather than illustration. Curated by John Szarkowski (who would later include Ohara’s ONE in the 1974 show New Japanese Photography and write the recommendation letter for his Guggenheim Foundation fellowship), the exhibition featured works by Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Gary Winogrand. These three photographers’ approach to image-making was guided by what Szarkowski described as “the belief that the world is worth looking at and the courage to look at it without theorizing."“Press release for New Documents,” The Museum of Modern Art, February 28, 1967, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/3860/releases/MOMA_1967_Jan-June_0034_21.pdf?2010.Other photo projects from this era echo Ohara’s experiments with repetition and everyday subject matter, like Takuma Nakahira’s Circulation: Date, Place, Events (1971), in which the artist photographed and printed his daily wanderings through Paris, and Bernadette Mayer’s Memory (1971), a month-long project where the artist shot a roll of film each day and kept a corresponding journal.

When asked about the photographers who shaped his practice, Ohara recounts the week when French photographer Henri Lartigue visited Richard Avedon’s studio in the late 1960s. At the time, Ohara was working as an assistant for the fashion photographers Avedon and Hiro, who shared a studio in Midtown. While watching Lartigue work, Ohara noticed that the older photographer related to his camera as an extension of his body, circumventing the expected choreography of taking photographs. Rather than crouching, standing, or changing positions to get a desired angle, Lartigue sat back, waited, and barely looked through his viewfinder. “How he shoots, you don’t feel it,” Ohara tells me. “It’s so soft.”

Ohara originally applied to the Guggenheim Foundation fellowship with a different project in mind. Already interested in limiting his control over the outcome of his images, he proposed a series of street photographs taken at night with a flash bulb. Although he was able to achieve the desired distance between subject and photographer, the pictures were not “soft”: the harsh interruption of the flash shocked unprepared pedestrians. Since he couldn’t see what he was shooting anyway, he thought: Why not just give the camera directly to the subject?

CONTACTS was the only time Ohara handed his camera over to strangers and invited them to make images of themselves. The decision to relinquish photographic control and collaborate with one hundred people scattered across the country challenged traditional conceptions of authorship and foreshadowed the social practice art that would flourish in the following decades. Ohara’s reluctance to control the narrative and meaning of CONTACTS is directly reflected in the radically collective and participatory nature of the work itself.

Carrying out this collaboration required a substantial amount of logistical and relational support. Ohara fielded questions by phone and letter, troubleshot problems with his camera, and ensured that each participant completed the assignment as quickly as possible. He tracked the camera’s path and mapped the location and duration of each stop it made in a meticulously organized notebook. The project also required instantaneous trust, and Ohara noted that he may have been the first Japanese person many participants had ever met. He outlined an idealistic hope for connection in the project description he sent with the camera: “The purpose of this project is to develop a feeling of trust and friendship between each one of us. The pictures you take will act as a bridge from one to another and, at the same time, the work involved before these pictures are taken will be of equal importance.” Each participant formed a link in a long line of connections, with Ohara serving as the central point of contact.

Ohara’s aspiration for connection across the vast space of America is especially striking given the work’s historical context. CONTACTS was created at the height of an economic crisis, in the wake of the Watergate scandal, as the final US troops were withdrawing from Vietnam, and in a time when separatist liberation movements emerged in the midst of continuing civil rights struggles. Like today, it was an era defined by precarity, social unrest, and deep distrust in a government that seemed more interested in carrying out imperialist projects abroad than feeding hungry Americans at home.

Against this tumultuous backdrop, Ohara envisioned and executed a project that hinged on a collective approach to image-making. Although cameras were becoming more accessible in the 1970s, some of the letters Ohara received highlight the meaningful impact of giving a camera to an ordinary person. One woman marveled at the “expanded vision” she found over the course of a few days: “At first my fingers felt like cucumbers, and I seemed to have three noses when trying to look through the viewfinder. By the third day I was calling myself ‘the photographer’! . . . Your whole project has been (forgive an old lady) a ‘mind blower.’”Dorothy Keilt to Ken Ohara, 1 August 1974, DOC.2025.37.1–100.9, Permanent Collection Documentation Office, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Keilt photographed CONTACTS 14, Keilt, Cresskill, New Jersey.By inviting people to document their own lives, Ohara advanced a democratic and open-ended form of social photography.

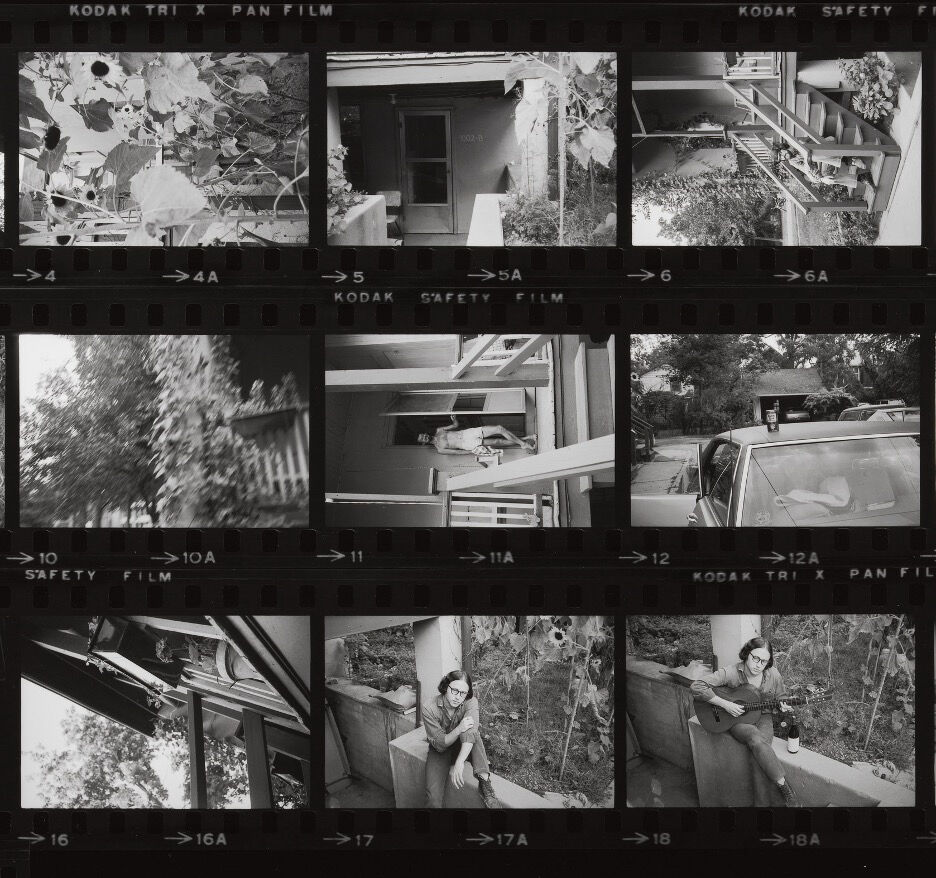

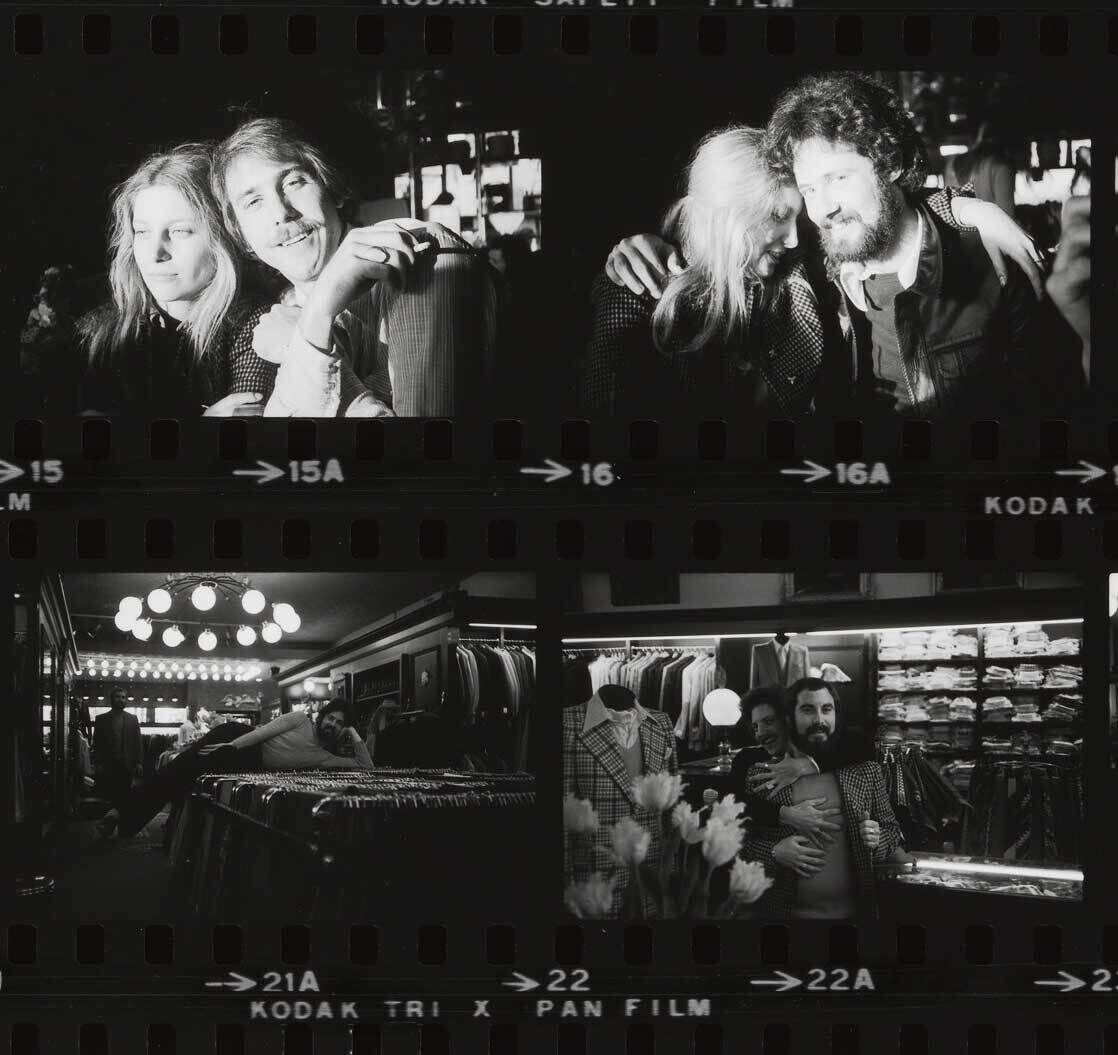

Looking closely at the contact sheets illuminates the range of vision the project achieved through collective authorship. In CONTACTS 10, Chu, Long Island, New York, it is possible to imagine the camera passing back and forth between mother and son as they swap poses, two artists and subjects collaborating on a summer day. Some sheets are quieter, with lives depicted in glimpsed details. CONTACTS 17, Stern, Ann Arbor, Michigan feels like a gathering of small facts shared in a soft-spoken voice. This is where I live, the pictures say, this is my friend, my roommate, my lover. This is someone comfortable being shirtless with me in the middle of sunflower season while I practice guitar. Other contact sheets are full of motion, like in Dan and Judy Radtke’s photographs of a snow day in rural Maryland—kids chase each other with snowballs, neighbors pose with tobacco leaves, a woman pulls water from a well, and the photographers drive into town to show us the diner and country store.

In the essay that accompanied Ohara’s 2006 retrospective at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, art historian Sally Stein observes that the images that compose CONTACTS show “hardly any signs of a growing counter-culture or a nation increasingly divided by debates about law and order, gender roles, and sexual liberation.”Sally Stein, “Face to Face: Ken Ohara’s Encounters with Photography,” in Ken Ohara: Extended Portrait Studies (Steidl/Folkwang Museum, 2006), 78.She is right that the progressivism of the 1970s is not overtly visible in the contact sheets. People go to work, hang out in their apartments, play with pets, and visit the doctor. This is, after all, a small sample of people making images they want to share with the artist. Perhaps CONTACTS can be understood as a different type of historical photograph: a collective visual history told through the accumulation of specificities rather than momentous events.

In the second installment of his three-volume text Critique of Everyday Life (1961), the French Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre writes toward a definition of everyday life, describing it as “a mixture of nature and culture, the historical and the lived, the individual and the social, the real and the unreal . . . in short a level of reality.”Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, vol. 2: Foundations for a Sociology of the Everyday, trans. John Moore (Verso, 2002), 47.CONTACTS takes this malleable “level of reality” and gives it a material form: each contact sheet tells the story of a distinct time, place, and perspective narrated in sequential frames. Despite everything going on at any given moment—socially, politically, culturally—these are the images people actually experience, the particularities that make up a day. In viewing these works, one becomes part of the experiment of CONTACTS, a participant tasked with making meaning from the samples of everyday life on view.