More Just and Joyful Futures:

Blossum Robinson’s Daufuskie Island

More Just and Joyful Futures:

Blossum Robinson’s Daufuskie Island

Before they touch the coast, the waves of the Atlantic break along the Sea Islands. It has been this way for five thousand years, since the end of an ice age led to rising water, and the Lowcountry’s highest ground reemerged as islands, separated from what is now known as mainland South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida by inlets, rivers, and salt marshes. These barrier and tidal islands shield the coast from storms, and their interaction with ocean currents nurture an abundant but delicate ecosystem for the people and creatures that live there. The same conditions that allow the Sea Islands to shield, sustain, and nurture life, however, also make them uniquely vulnerable to the ravages of climate change and the rippling consequences of pollution and commercial development.

In 1974, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe spent several months of her junior year of college making photographs in West Africa. On a visit to Cape Coast Castle in Ghana, she cast her eyes out across the water. “I was profoundly impacted,” she remembers, “by looking out of that porthole to the ocean and looking west and thinking about that journey from Africa to America. There were fishing villages on the west coast of Africa, and there were fishing villages and communities on the southeast coast of the United States. I drew right then a relationship between the two.” Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, “An Oral History with Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe,” by Kalia Brooks, BOMB Magazine, September 11, 2014, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2014/09/11/jeanne-moutoussamy-ashe/.For centuries, commercial forts like Cape Coast Castle functioned as temporary prisons and final ports of call for enslaved African people en route to the Americas. For many, the Sea Islands would be the first bits of land they saw after that crossing; for some, they were also the last. This is information Moutoussamy-Ashe already knew, but she beheld it differently there in her body, looking back toward the place from which she had come.

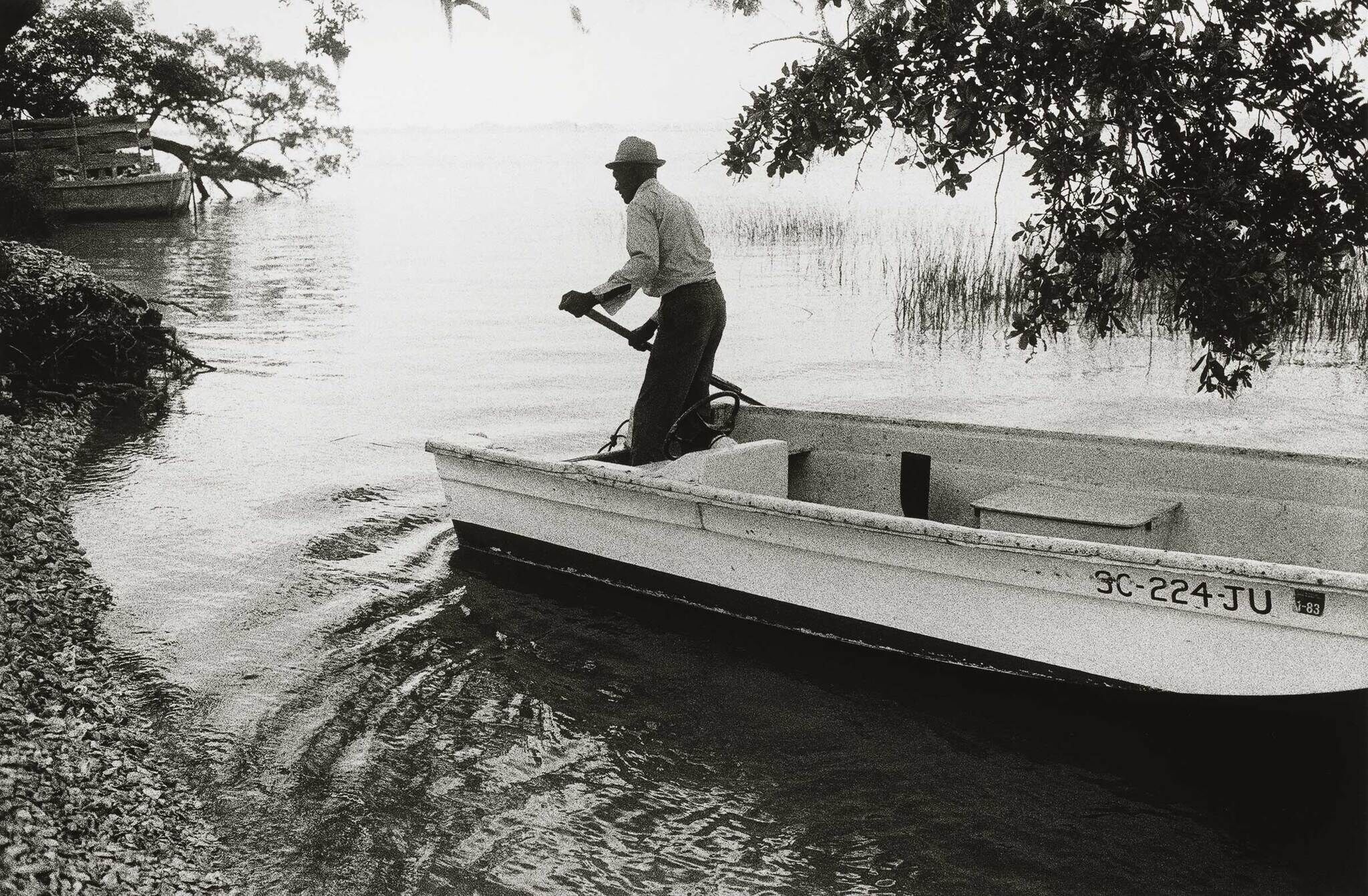

A few years later, in 1977, the artist made her way to the Sea Islands. She landed first on Edisto Island and then, on the advice of a friend, the self-styled “culinary griot” Dr. Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, traveled to Daufuskie—the only South Carolina Sea Island unconnected to the mainland by a bridge. Though the journey from neighboring Hilton Head Island to Daufuskie is not long (about forty-five minutes by boat), its relative inaccessibility allowed it to endure as a holdfast of Gullah Geechee language, culture, and customs for much of the twentieth century.

Daufuskie, or “D’awfoskee” as it was originally written, is a Muskogean word that means “sharp feather”—a reference to the tapered shape of the island’s land mass. There are some who claim the island’s name originates in Gullah and refers to “da firs key” (the first key), highlighting Daufuskie’s positionality as the first landmass one might encounter on a journey west across the Atlantic. As Moutoussamy-Ashe points out, although this is disputed, “it makes sense that the Gullah would find this music in their language and speech.”Spanish and English explorers reached the island as early as the sixteenth century and, by the eighteenth century, had violently expelled the indigenous Cusabo people, who were left to join neighboring Muskogean tribes. The labor of enslaved African people led to booming indigo and cotton industries on the island, while the same bountiful oyster beds that had provided for the Cusabo continued to feed Daufuskie Island’s new and growing population. When the white plantation owners were driven off the island by occupying Union forces at the end of the Civil War, the land was acquired by the freed Gullah Geechee—formerly enslaved African people and their descendants.

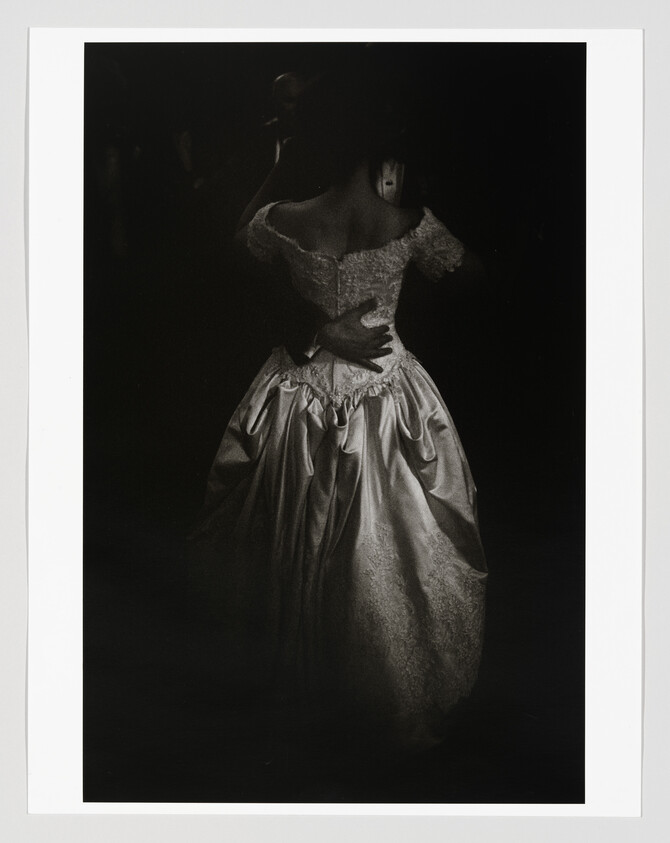

For some time thereafter, the existing agricultural infrastructure and the island’s natural gifts sustained the Gullah Geechee. But the arrival of the boll weevil in the early twentieth century destroyed Daufuskie’s cotton fields, and industrial pollution from the Savannah River poisoned the island’s oyster habitats, forcing local canneries to close and leaving a majority of Daufuskie’s residents without work. After World War II, neighboring Hilton Head Island was developed as a profitable tourist destination advertising luxurious resorts and golf courses. Inevitably, real estate developers began to eye Daufuskie, preying upon the families that still lived there, many of whom were facing economic hardships, in order to buy up unspoiled land. When Moutoussamy-Ashe arrived, there were just eighty permanent residents left—more than half of whom are pictured in the artist’s 1980 portrait of a wedding party, titled The Bride, the Groom, and their Guests, Daufuskie Island, SC.

The image of the wedding party is the final plate in both Moutoussamy-Ashe’s original 1982 book, Daufuskie Island, A Photographic Essay, and in the expanded 2007 edition. In the forty-three years since the first edition of the book came out, the artist has often framed the years she spent photographing Daufuskie as beginning and ending with Lavinia “Blossum” Robinson. Robinson was born on the island around the year 1900, and her warm smile and weathered face begin the plates section of the book’s twenty-fifth anniversary edition. Robinson’s portrait also greets visitors to the Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands with The Bride, the Groom, and their Guests, Daufuskie Island, SC hung beside it.She was the island’s great matriarch—everyone’s mother, everyone’s grandmother, kind, wise, dubious, and (sometimes, when needs must) wrathful. In January of 1982, while Moutoussamy-Ashe was finishing up her book, she received a call from Daufuskie informing her that Robinson had died and imploring her to come back and bear witness through the camera lens.

Robinson’s passing would be witnessed by a wider world than the one in which she lived. Moutoussamy-Ashe photographed her burial, producing a breathtaking, gut-wrenching series of images that shows Robinson in her white, satin-lined casket, surrounded by mourners as she is lowered into the ground. As the artist would write in the preface to her 1982 book, “a Daufuskie Island institution had come to an end. . . .it was an almost poetic ending to the devastating changes about to take place on Daufuskie.”Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Daufuskie Island, A Photographic Essay (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1982), xvii.

If Robinson’s passing marked the end of an era for both the islanders and the artist, why, then, are the images that Moutoussamy-Ashe made of Robinson’s burial not the images that close out her book?

Ending with the wedding portrait is, I suspect, the artist’s expression of faith in Daufuskie’s future: a union and a promise and a commitment, celebrated in community and in joy. Though Robinson’s death in 1982 may have marked the end of one chapter of the island’s history, that history and the Gullah culture it grew are carried forward by those who believe in its worthiness and continue to take responsibility for its safekeeping. One such person is Dr. Emory Shaw Campbell, who was born on Hilton Head Island in 1941 and who served as Moutoussamy-Ashe's guide during her first trip to Daufuskie Island in 1977. An elder now himself, Dr. Campbell has continued to educate visitors on the history of the Gullah Geechee and to advocate for cultural and environmental conservation across the Sea Islands as the executive director of the Penn Center on St. Helena Island. There is also Sallie Ann Robinson, Robinson’s granddaughter, whose nonprofit Daufuskie Island Gullah Heritage Society raises money for historical conservation projects like the tending of the island’s cemeteries. Her cookbook, Gullah Home Cooking the Daufuskie Way, compiles many of the island’s most tried-and-true recipes (including her grandmother’s woodstove cornbread) to nourish readers who have never been to Daufuskie, alongside those who are homesick for it.

Standing in front of this photograph with Moutoussamy-Ashe on the opening day of Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands, I confided to her that I was preoccupied by the manner of Robinson’s appearance. Why is this “Daufuskie Island institution” standing on the outskirts of her community? Why is she not embraced and at the heart of things, as an elder of (then) eighty years, born on the island, ought to be? The artist laughed. “But that was Blossum! Keeping an eye on things and waiting for me to take the damn picture!”

When Robinson was born on Daufuskie Island in or around 1900, there were between two and three thousand people living there. She would have been a young woman when the boll weevil came and destroyed the island’s cotton fields. She would have watched her neighbors move away—slowly, at first, then in droves at midcentury, once the oyster canneries closed and folks moved away to find work. The year before Moutoussamy-Ashe photographed The Bride, the groom, and their guests, Hurricane David buffeted Daufuskie with seventy to ninety mile-per-hour winds, taking down a centuries-old praise house and leaving other historic structures on the island in an increasingly precarious state before moving along—weakened—to the mainland.

Although Moutoussamy-Ashe remembers being welcomed warmly to Daufuskie, she also recalls that many of the people she met and photographed there didn’t see much value in the pictures she was making until after the hurricane—including Robinson, who teased her mercilessly when Moutoussamy-Ashe visited her at home to make her portrait in 1979. As it turned out, a single storm could level a Daufuskie institution with very little trouble. But then, that which exists only in memory is granted a certain kind of immortality through the photographic image, recorded in light and testifying to its own place in history.

It is difficult to contemplate the loss of a person such as Blossum Robinson, who bore witness to Daufuskie’s changing tides for most of the twentieth century and weathered its many storms. At her funeral, friends and family joked that Robinson ought to be down at the dock, shaking her fist at the developers as they ferried cranes and construction equipment over to the island. Stalwart at the shoreline, on the edge of her community, at the end of an era (or of a book), keeping an eye on things: there’s Blossum, waiting for somebody to take the damn picture.