Misdirection as Resistance

In Ilana Savdie’s painting Baths of Synovia (2023) there is a small, multi-hued hand perched outside of a dark blue hole. The detail, dwarfed by the disorderly commotion of abstract forms depicted above it, is easy to overlook. Upon closer inspection, it is unclear whether the hand is emerging from the hole or receding into it. Is it resisting an undetermined fate, or is it succumbing to it? Or is the hand playful and announcing its return (or departure) as it rises from (or descends into) the unknown?

Savdie’s works instill a sense of ambiguity in the viewer that some may find disorienting. The cryptic hand motif, for instance, is caught between contradictory tonal shifts. Savdie’s paintings and drawings are known for their abstracted amalgamations of human bodies, animals, folkloric and animated characters, and microorganisms. For her works on canvas, the artist uses a lurid color palette composed of bile greens, oozing yellows, fiery reds, and bruise-like blues and purples. She mixes pigment and beeswax to create sublime skin-like fields across the canvas. Her brushwork is captivating in its technical precision and extravagant theatricality. The corporeal oddities she creates oscillate between familiar and unfamiliar, alluring and terrifying, but their peculiarity seems to stem from the fragments’ resemblance to our own bodies and their interactions with other forms. A disembodied foot, a ribcage, sagging flesh—these remnants are scattered throughout Savdie’s compositions, merging with biomorphic shapes, piling up on top of each other, and coalescing into a spectacular chaos.

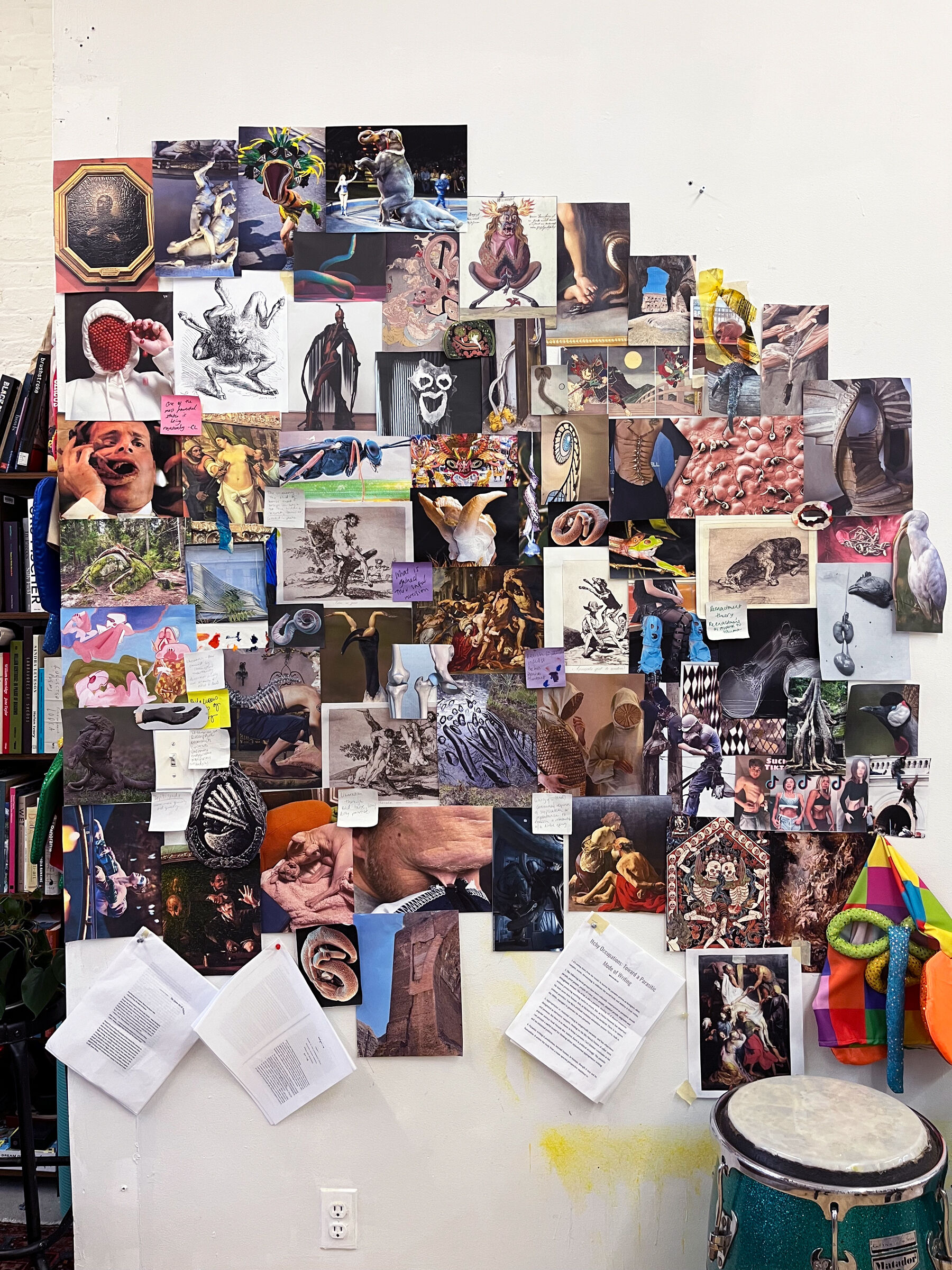

Before beginning a new body of work, Savdie consults the curated selection of visual references she keeps on her studio wall, many of which are drawn from science, politics, art history, horror, animation, and pop culture. Recurring images include micrographs of parasites, photographs of the January 6 US Capitol attack, Baroque paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, stills from the television horror show Dark Skies, frames from The Ren and Stimpy Show, and screenshots of the “sucking stomach” challenge on TikTok. True to Savdie’s artistic form, each source focuses on the body, emphasizing how vulnerable and malleable it can be. These images not only inform the artist’s aesthetic and compositional decisions, but they also offer much to contemplate about the different ways bodies shape human existence, politicize individuals, and give form to collective anxieties.

When describing the works on view in the exhibition Ilana Savdie: Radical Contractions, Savdie cites the allegory of the boiling frog. As the story goes, if a frog is placed in boiling water, it will immediately try to escape. However, if a frog is placed in lukewarm water that is slowly brought to a boil, it will not notice and be boiled alive. This gruesome tale is a warning about the dangers of ignoring the gradual advances of an incoming threat. It also effectively conveys the foreboding themes underpinning Savdie’s work. Before creating her most recent paintings and drawings, she was thinking about “[various] threatening bodies moving in lockstep, taking an organized position, and no longer being coy about that position . . . . something about this moment feels as though the water is starting to boil—we’re kind of in it.”Ilana Savdie, interview with the author, May 29, 2023.

Usually, a conflict of any kind involves two or more opposing forces, but it is uncertain who or what is caught in the disorder Savdie creates. In Pinching the Frenulum (2023), several human limbs, fragments of zebra skin, and forms that resemble glistening internal organs are colliding with one another while a large tentacle coils around the central action, implying restraint and constriction. All that can be gleaned from the propulsive energy vibrating off the canvas is an overwhelming tension, which is made apparent by exaggerated movements—tugging, pulling, coiling, clashing, and wrapping. Savdie homes in on these specific actions because they are the body’s instinctual response to an external threat. Whether it’s found in a gesture, or the way paint is applied to the canvas, the formal qualities of Savdie’s work are often guided by the choreographies of survival.

Displays of conflict and struggles for power—both physical and ideological—can be readily found in social and political arenas across the globe, so it is easy to imagine how recent events, particularly in the United States, have shaped Savdie’s representations of the body in her work. Since the 2016 election, the country has experienced a heightened sense of unease and agitation as a result of an increasingly fractured political landscape. This polarization has largely been galvanized by discourses focused on bodily autonomy, which have been and continue to be especially consequential for marginalized communities. In the first half of 2023, nearly five hundred anti-LGBTQIA+ bills were introduced in state legislatures“Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures,” American Civil Liberties Union, last updated September 29, 2023.; fourteen states passed abortion bans in the six months after Roe v. Wade was overturned by the Supreme Court“Tracking Abortion Bans Across the Country,” New York Times, last updated September 29, 2023.; gun violence continues to rise with more than five hundred mass shootings recorded in 2023 so farGun Violence Archive, last updated October 3, 2023.; and, as the climate crisis intensifies, predictions about the viability of life on earth are becoming grimmer.

The water is coming to a boil. To live through these real-life horrors is to subject our bodies to an insurmountable sense of dread. Admittedly, this feeling puts into perspective how hopeless one can feel in the face of so many compounding disasters. And yet, despair begets indignation and casts a harsh, critical light on the systems of power that led to these catastrophes. An interrogation commences: Who or what has the ability to exert that kind of power? What mechanisms of control are used to obtain, establish, and enforce it? And how can these structures of power be mitigated, survived, or even resisted?

Intriguingly, the genres of horror and comedy prove to be especially useful frameworks for understanding Savdie’s thinking around power, adversarial relationships, and embodiment. On the surface, the two genres seem like opposite modes of expression. Horror typically produces fear and panic, while comedy generates laughter and amusement. Yet, scholars of film, literature, philosophy, and theater insist that both genres are quite similar, even if they elicit different responses. As philosopher Noël Carroll argues, horror and comedy share a narrative trope: they place characters in vulnerable situations that problematize and transgress certain rules and expectations we have about our bodies.Noël Carroll, “Horror and Humor,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 57, no. 2 (1999): 152.In horror, this often takes the form of an attack by a monster, demonic possession, or an involuntary transformation that changes the character from human to otherworldly being. The threat of pain or bodily harm induces fear because it implies a lack of power and control over one’s body. Comedy also relies on the absence of bodily control, but, instead of provoking terror, the depiction of slapstick mishaps inspires laughter.

Horror and comedy create tension through corporeal insecurity and resolve it by disrupting expected outcomes centered on the body’s ability (or inability) to adapt to and survive external conditions. As comedian and author David Misch affirms, “all comedy and all horror establish patterns that introduce tension then resolve in a surprising way, often using misdirection.“David Misch, “Ha!/Aaah!: The Painful Relationship Between Humor and Horror,” in Horrific Humor and the Moment of Droll Grimness in Cinema: Sidesplitting Laughter, ed. John A. Dowell and Cynthia J. Miller (Washington DC: Lexington Books, 2018), 74.It is through this use of misdirection that the narrative strategies of horror and comedy become the formal and thematic innovations found in Savdie’s paintings and drawings. When the artist flings paint onto the canvas, the mark can evoke a grisly blood splatter or snot after a hearty sneeze. These formal diversions guide the viewer's attention and undermine their expectations. Likewise, the exuberant color palette may position a viewer to expect a pleasant composition, but once the mass of contorted figures comes into focus the grotesque nature of the forms is revealed.

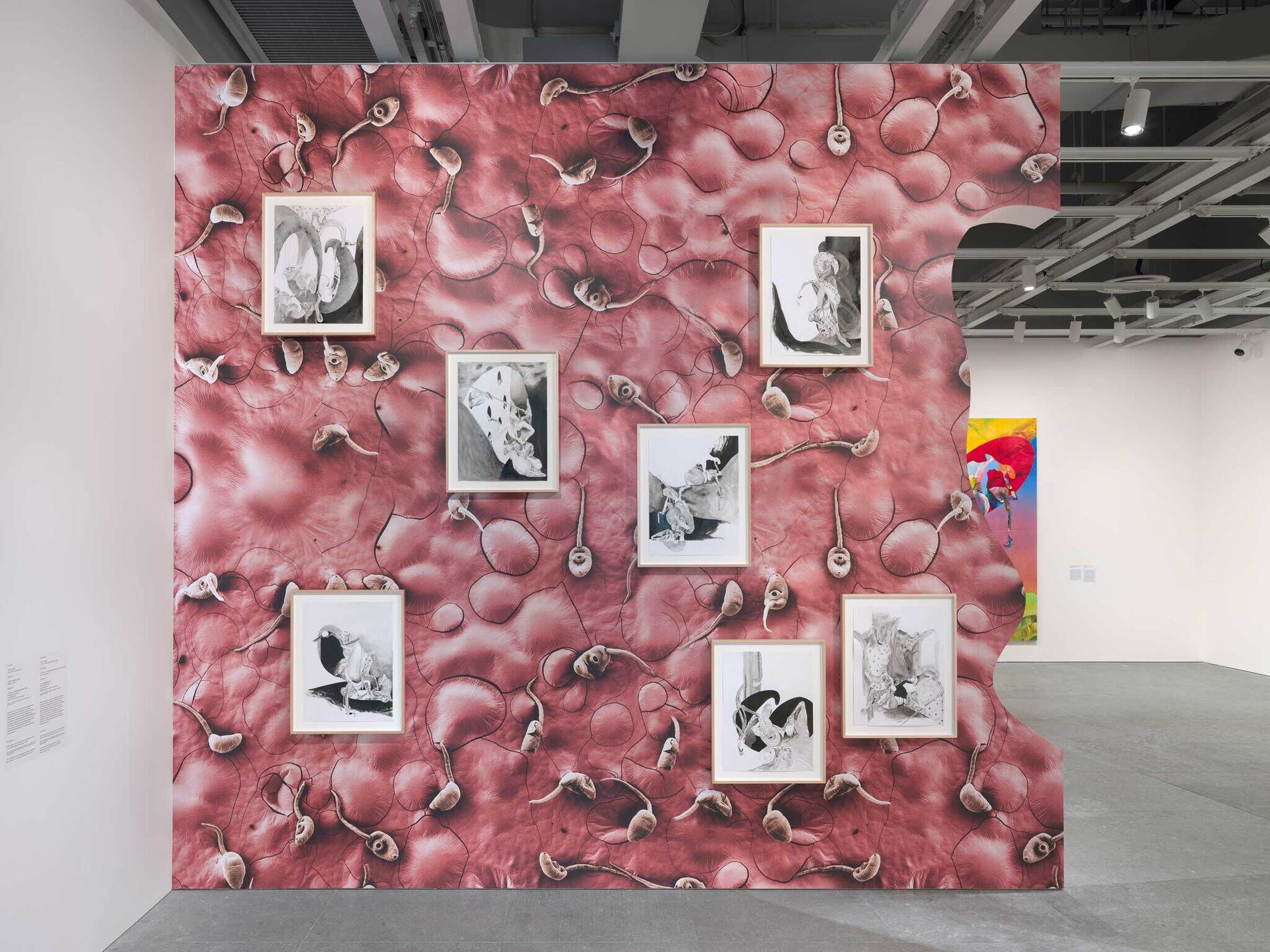

Savdie’s use of misdirection as a visual tactic is also modeled after the behaviors of parasites. Parasites appear as small orange larvae in Pinching the Frenulum and enlarged technicolor worms in Helminth (both 2023). These microorganisms often extract the resources needed for survival by living in or becoming a part of their host using mimicry or physiological changes. Misch acknowledges that “in both comedy and horror, bodies out of control are scary because they challenge our belief that there’s order in the world . . . . That’s why the idea of possession has such power; our need for order makes us frightened when it disappears. But it’s also funny; people being controlled, or out of control, say and do things that are usually forbidden.”Misch, “Ha!/Aaah!,” 79.For this reason, moralistic judgment is cast upon parasites, and they are often regarded as the thieves or grifters of the biological world. But Savdie prefers to see them as “agents of change” because they embody the provocative potential of transformation.Savdie, interview.Writers Post Brothers and Chris Fitzpatrick echo this attitude: “Parasites reveal the complexity of all given relations between things . . . as well as how parasites render binaries worthless. What emerges from this clarity of vision is the ability to study and disrupt those relations. How parasites shift according to certain rules and how their hosts must shift according to their parasites is the very point of parasitic gestures—it is how parasitic gestures become more than gestures. It is how they effect change.”Post Brothers and Chris Fitzpatrick, “A Productive Irritant: Parasitical Inhabitations in Contemporary Art,” Fillip, Fall 2011.

Savdie’s interest in misunderstood beings also extends to folkloric characters such as tricksters. The marimonda, a jester-like figure that takes part in the annual Carnaval de Barranquilla in Colombia, appears frequently in her work. Donning a mask that combines the features of a monkey and an elephant, the marimonda performs exaggerated choreographies originally intended to mock the social elite. The artist draws broadly from the trickster’s ethos, specifically their proclivity for engaging in mischief and mockery as forms of resistance. In Anquilosis (2023), the marimonda is a deflated cartoon phantom entangled within a knot of other forms—a polychromatic appendage gripped tightly around its neck. Despite the obstructions it faces, the specter persists and tries to wedge itself into the chaos by overexerting its rubbery elasticity. Although they are characterized as nuisances, tricksters practice a transgressive refusal of traditional social norms. When the world becomes too overbearing and authoritarian, they break rules, cross boundaries, and invent new ways to overcome such stifling realities.

For Savdie, the trickster’s penchant for defying convention finds contemporary parallels with animated characters. Like the trickster, cartoons are elastic: they bend, twist, and shapeshift. Moreover, their conceptions of space and time can be reconfigured at any point. In Radical Contractions, the hole or portal, a relatively new motif, appears in paintings such as Baths of Synovia, Tickling the Before and After, Anquilosis, and Pico y placa (all 2023). The hole provides a way for Savdie to “imply an architecture that is never quite there.”Savdie, interview.The shape is flat, but it offers a sense of depth, which allows the figures in her work to reach into one portal and exit through another, as seen in Pico y placa. The artist also affirms that the holes function in a rather cartoonish way. One visual reference is the portable hole that appears throughout the Looney Tunes animated universe—most famously in the short film titled “Fast and Furry-ous.”“Fast and Furry-ous,” Loony Tunes (Los Angeles: Warner Bros. Cartoons, Inc., 1949), 7:07 min. In the short film, Wile E. Coyote makes multiple failed attempts to capture the elusive Road Runner. The most iconic scene finds Wile E. painting a receding tunnel onto the side of a mountain. Wile E. hopes that Road Runner will believe it is an actual tunnel and crash into the wall, rendering him immobile and, therefore, easier to capture. However, Wile E.’s plan fails. Instead of colliding into the faux tunnel, Road Runner is able to turn the tunnel into a portable hole and continue running, thereby making his escape. A confused Wile E. attempts to do the same but falls for his own trap.In animation, portable holes can be read as defense mechanisms: clever methods of surviving the nefarious intentions of those who seek to inflict harm. However, the portals in Savdie’s work expand and disrupt the physics of her visual world. They enable the artist to break her own aesthetic norms.

Savdie’s work underscores how human experience is mediated through our bodies. In her surrealistic abstractions, fear, mockery, and resistance manifest simultaneously, revealing the range and complexity of our emotional responses. The exhibition’s title, Radical Contractions, derives from the scientific definition of laughter as audible contractions of the diaphragm. The title also alludes to Mikhail Bakhtin’s theorization of the carnivalesque, which positions laughter and revelry as subversive acts.Mikhail Bakhtin, “Rabelais in the History of Laughter,” in Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky (Indiana University Press, 1984), 88–94, 122–123.So even as the title alludes to a joyful response, it also invites other interpretations. Yes, our diaphragm contracts when we laugh, but it also contracts when we scream or cry. Savdie’s paintings and drawings grapple with the horror of corporeal vulnerability—the ways our bodies are so determined by our limitations. And yet, redemption arrives in the form of parasitic gestures and trickster ingenuity. Misdirection, transformation, and an unwavering refusal to conform are tactics that force open other possibilities. Perhaps screaming is an appropriate response when confronted by such dangers, but we can also laugh.