Eckhaus Latta:

Possessed

Group Dynamics

The last ten years have proven to be a fertile time for young New York fashion designers, who have injected new energy into the fashion industry as well as art and culture more broadly. While the Whitney does not often mount exhibitions on fashion—Eckhaus Latta: Possessed is the first in twenty-one years—recent work by emerging designers has dovetailed with concerns key to many young artists including the fluidity of identity and its relationship to images; the dissemination of a brand, whether it be personal or corporate; and an omnivorous perspective that draws from different disciplines as well as various notions of taste. The parallels between certain designers and artists offer a vantage point from which to observe one industry from the perspective of the other. Fashion—which is constituted of those who design and realize collections of clothing, the garments themselves, the constant cycle of what is in and out of mode, and the mechanisms that serve to announce the season’s new trends—is a system that is not unlike the art world but operates on a different tempo. While the goal of fashion is to reflect, or even anticipate, the current moment, a marker of success in the art world is having one's work acquired for a major museum collection, where it will be kept safe for future generations to study and enjoy.

The work of emerging designers has reached beyond traditional fashion clientele to wide audiences, entering into conversations on art, music, and film. New York–based labels like Telfar (launched in 2005) and Hood By Air (2006–2017) have, in their own distinct ways, examined twenty-first-century notions of consumer identity, branding, and subculture. Adding to this interdisciplinary mix is Eckhaus Latta, founded by Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta in 2011. The design duo has found inspiration from the wide variety of materials they employ, a reflection of their training in sculpture and textiles during their undergraduate years at the Rhode Island School of Design. Their deeply collaborative practice involves not just the two designers at the helm, but draws on the work of artists, architects, graphic designers, musicians, filmmakers, and other creative individuals that now span New York and Los Angeles. While it’s no secret that it takes a team, if not a small army, to produce two seasonal collections a year, Eckhaus Latta is transparent about their collaborations, insisting on naming those who help them do what they do. Their practice is emblematic of what is necessary today: it is equally dependent on its followers on social media and the relationships it builds with real people. Eckhaus and Latta have helped foster emerging voices in a number of fields, all the while creating an incisive label that reflects the contemporary moment.

Eckhaus Latta’s runway shows further demonstrate the duo’s collaborative sensibility. Past presentations have included a minimalist soundtrack performed by Dev Hynes, a vegetable-laden set created by Alex Da Corte, and a text-based shirt collaboration with artist and musician Brendan Fowler. Their choice of models—both professional and nonprofessional—is telling. Artist and former fashion designer Susan Cianciolo, gallerists Bridget Donahue and Lucy Chadwick, collector and patron Thea Westreich Wagner, publicist Cynthia Leung, and artists Juliana Huxtable, Torey Thornton, and Maia Ruth Lee (who was pregnant during the spring/summer 2018 show) have all walked in Eckhaus Latta’s shows. In bringing together a group that cuts across age, race, body type, and gender, Eckhaus Latta is not making tokenistic gestures of inclusion but rather showcasing many of the individuals who are a part of their creative and social circles and who have inspired their practice. For example, Susan Cianciolo, who has walked for them over many seasons, has been an important influence on Eckhaus and Latta. An artist and designer who first emerged in the 1990s, Cianciolo is known for pushing against the fashion industry by refusing to mass-produce her designs. Through her broad and generous vision, she has collaborated with Mississippi-based quilters and incorporated culinary happenings and filmmaking into her work.To further complete the circle, Brendan Fowler had worked at Alleged Gallery, which was founded by Cianciolo’s former husband Aaron Rose and was where she first installed her RUN RESTAURANT in 2001. RUN RESTAURANT was reprised as part of the 2017 Whitney Biennial, which I curated with Mia Locks.For her—as well as for Eckhaus and Latta—the lines of distinction between art, fashion, and culture are blurry or perhaps no longer useful or relevant.

Eckhaus Latta’s designs are meant to be open to the interpretation of the wearer, intended to integrate into one’s wardrobe to reflect the style and identity of the possessor. While some tops and dresses are designed for a specific gender, the designers’ views of sexuality and gender acknowledge a gradient of identities instead of strict binaries. Rather than allow the clothes dictate who one ought to be, Eckhaus Latta creates “lapped” T-shirts, knit sweaters, and unisex jeans that can be worn with one’s favorite oversized wool coat or pencil skirt, conforming to the look of the wearer in a more charitable manner than, say, the closed loop of Balenciaga’s fall 2017 menswear collection that featured a hoodie branded with the logo of its own parent company Kering.David Lieske, “Fashion: The Fall Collections.” Artforum 55, no. 9 (May 2017): 115–16.While the young designers’ intent is to bestow agency upon the wearer, they do not shy away from the untraditional. They have applied rust onto denim pants and vests, employed sheer fabrics—which they call “fluid”—for dresses and tops, and created elaborate one-of-a-kind pieces, such as their autumn/winter 2015 light blanket coat made from a found throw festooned with knitted Italian mohair and acrylic paint.

All of this speaks to their broader conception of identity, which they see as mutable and largely self-fashioned. Through their clothes they aim to offer a wider notion of fashion, going beyond the restrictive definitions established by mainstream brands. In an interview on authenticity, Latta has said, “I think the Eckhaus Latta customer relates to how we’re trying to provide an alternative to standardized norms of beauty, or size, gender, and race.”Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, “Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta.” Vestoj, no. 8 (winter 2017): 234.And yet the designers recognize that there are certain limitations to a brand and its accessibility. Speaking of their label, Latta continued, “It can be exclusive in other ways. It’s only sold in a few, upmarket stores; not everybody would feel comfortable going to Dover Street Market.”Ibid., 236.Or, to put it another way, here are a few lines from their autumn/winter 2018 press release written in the form of a poem (a form favored by the designers):

THE TEST RESULTS WERE POSITIVE:

WE’RE ALL PAYING TO PLAY.

YOU COULD HARDLY BREATHE AND YOUR ASSIGNED EMOTIONAL

SUPPORT ANIMAL WAS ALSO VOMITING

In 2017, Eckhaus Latta was invited to edit issue number 17 of A Magazine Curated By, a biannual publication that invites a different designer to “curate” an issue. Latta and Eckhaus modeled theirs after an advertisement-filled September issue of a mainstream fashion magazine, like Vogue, that marks the start of a new year of fashion. Eckhaus Latta’s publication is their take on each of the key sections: front matter dedicated to gossip and party photos; commissioned feature articles, photo spreads, fiction, poems, and interviews—all interrupted intermittently by fake ads by real artists; and traditional back matter, such as horoscopes, advice columns, and personal ads. At once sincere, candid, humorous, and ambitious, the issue functions at different levels for different audiences. For their fans, it serves as a document of so many past designs and collections. For those who are closer to their social sphere or interested in the contemporary art world, there are humble sparks of recognition in knowing that the back-page ad for the Horny Surf Club memorializes the beach forays of Latta and her friends, such as Rob Kulisek, Matthew Lutz-Kinoy, Amy Yao, and others; or that the cover story was shot by Roe Ethridge—an artist who both makes commercial photographs and appropriates the visual vocabulary of such images in his art. Eckhaus explains, “When developing A Mag it felt essential for us to play with the language of advertising since it has such a large role in printed fashion media. . . . It was a fun way of including a wide range of people that we are close with, admire, and have worked with in the past to explore something that is rather distant from the medium and language most of them often work in.”Mike Eckhaus, email to the author, July 2, 2018.These are connections that are both playful and giving, not intended as a game for insiders only, but as a way to invite everyone in to a kind of all-encompassing inner circle. Perhaps the “Spotted” section of the publication puts it best. The headline accompanying photos of the Eckhaus Latta team on the streets of New York and Los Angeles reads: “They are just like us."A Magazine Curated By, no. 17 (September 2017): 40.

Possessed, Eckhaus Latta’s installation at the Whitney, looks to the broader fashion industry, training a lens on how emotional connections—desire, seduction, attraction—are produced and manipulated. This often first occurs through marketing and advertising, which can disseminate a brand’s message before consumers have any physical interaction with its clothing. Even though physical retail stores are in decline in the United States, the shopping experience is still a major way for designers to articulate their vision through the immersive experience of a flagship store. The layout of the space, lighting and music choices, and imagery all contribute to the atmosphere of the store, whether or not customers are conscious of it. As Roland Barthes wrote in his foreword to The Fashion System: “In order to blunt the buyer’s calculating consciousness, a veil must be drawn around the object—a veil of images, of reasons, of meanings; a mediate substance of an aperitive order must be elaborated; in short, a simulacrum of the real object must be created, substituting for the slow time of wear a sovereign time free to destroy itself by an act of annual potlatch.”Roland Barthes, foreword to The Fashion System, trans. Matthew Ward and Richard Howard, 2nd ed. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990), xi–xii.

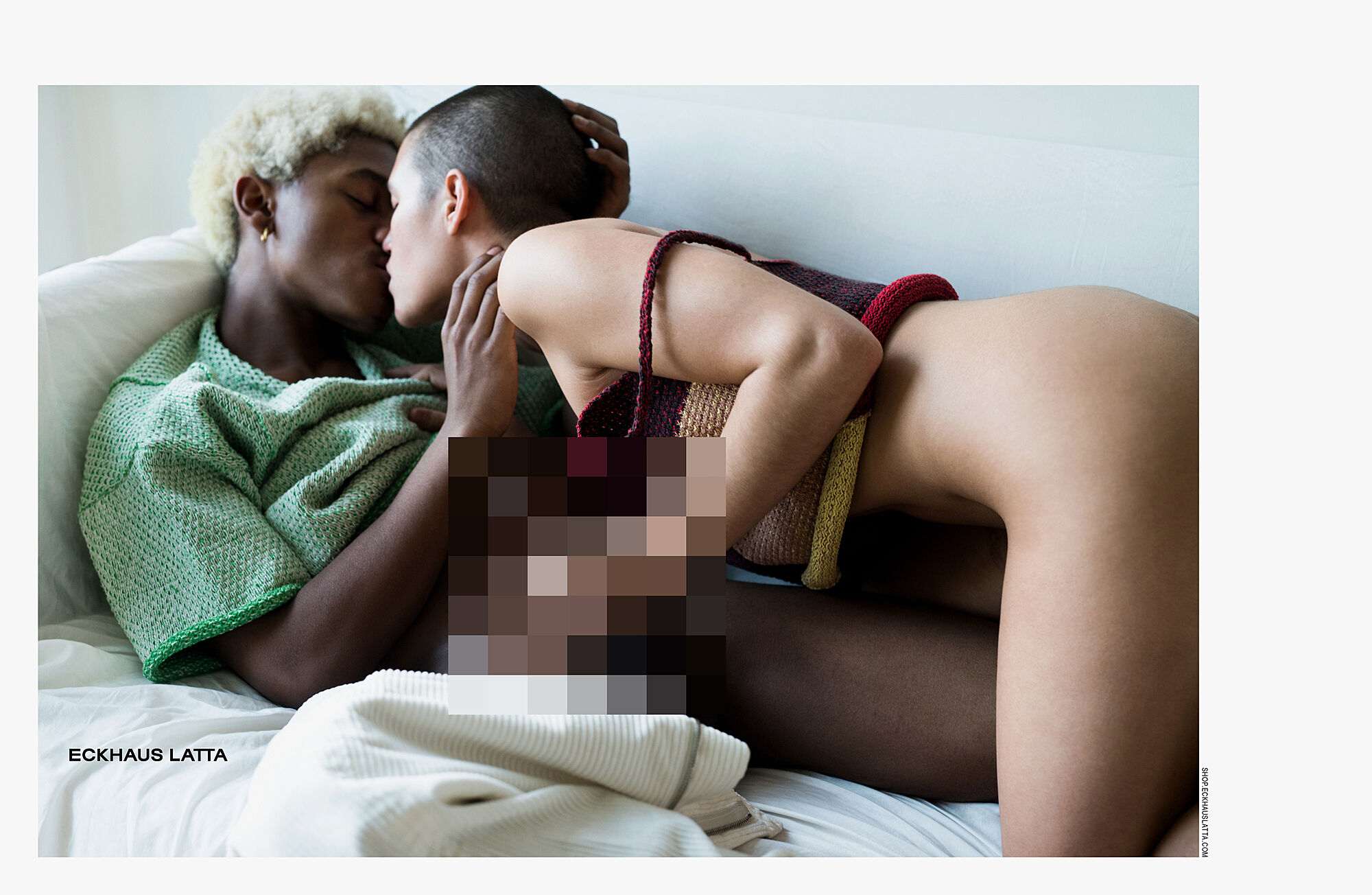

The veil is what Eckhaus Latta both draws down and pulls away in this exhibition. The images the viewer first encounters in the installation knowingly toy with the look of iconic fashion advertisements. The label’s past campaigns typically seduce in a quotidian way. Whether presenting a motley crew of cool kids lounging in bed or a forlorn middle-aged woman seemingly abandoned on an L. A. sidewalk wearing a necklace of dried pasta, the image they project is a far cry from the luxurious fantasy of high fashion. Eckhaus Latta has so eschewed lofty escapism that their spring 2017 campaign featured images of real couples engaged in sex (with some strategic blurring added in postproduction). The duo’s decision to open Possessed with glamorous images is not intended to make fun of the work of, say, Richard Avedon or Steven Meisel. Instead, it is an act of homage to the long lineage of photographers and models that created the look of fashion. And yet, Eckhaus Latta’s photographs stand apart from so many fashion spreads because of their inclusion of a far more diverse cast than their luxe counterparts.

The installation leads with fashion images in the way that one often encounters ads from a label before the clothes itself. Possessed traces this arc and, in the following section of the exhibition, presents an operational retail environment that offers a direct experience with the clothing by enabling visitors to handle and try on the line made specifically for the show. Exhibitions traditionally privilege sight above the other senses, but for fashion exhibitions this is at the detriment to the experience of clothes that are meant to be worn and used. Retail spaces in general encourage active engagement, albeit to drive sales. For Eckhaus Latta’s installation the option to purchase garments is available, though the ultimate motive is for Museum visitors to learn firsthand about the label and its designs. The special collection itself is what the designers call an “introduction” to the label, a line of clothing that utilizes silhouettes and forms that have become associated with Eckhaus Latta, and are here produced in novel fabrics and colors, in addition to new treatments to vintage shirts, one-of-a-kind knitwear, and beaded vests that reside in the space in between jewelry and garment.

Inherent in exhibiting fashion is the challenge of intimating the real-life use of garments. Fashion historian and curator Anne Buck wrote in her 1958 Handbook for Museum Curators: “The beauty of dress, always ephemeral, is so closely connected with the living, moving body which wore it and gave it final expression, that a dress surviving, uninhabited, may appear as an elaborated piece of fabric, an accidental repository of the textile arts, but little more.”Quoted in Amy de la Haye, “Exhibiting Fashion Before 1971,” in Exhibiting Fashion: Before and After 1971, by Judith Clark, Amy de la Haye, and Jeffrey Horsley (New Haven, CT, and London, UK: Yale University Press, 2014), 54.From 1947 to 1972, Buck was the curator of the Gallery of English Costume at Platt Hall, Manchester, the first UK museum focused on costumes and dress.Ibid., 50. See also, Veronica Horwell’s obituary for Anne Buck in The Guardian (UK), June 3, 2005.She was a pioneering figure who, in order to demonstrate the construction of garments, allowed visitors to try on dresses from the collection and be photographed in them with full make-up. The practice ultimately came to an end in order to prevent the garments from being damaged through use and exposure to human sweat.

More recently, Australian fashion curator Matthew Linde has been experimenting with the form of fashion exhibitions. From 2013 to 2016 he ran the exhibition space Center for Style in Melbourne, where he invited local and international artists to participate in exhibitions and performances that presented clothing and visual art side by side without hierarchy. In 2017, Linde organized The Overworked Body: An Anthology of 2000s Dress at Mathew Gallery and MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38, both in New York’s Lower East Side. For the closing performance models wore the garments that had been on display and walked the block between the two venues. Not only did this set the garments and their wearers in motion but it brought the pieces back onto the street, a kind of temporal rewind to the downtown New York of the early aughts.

The retail environment of Possessed is where Eckhaus Latta’s collaborative process is most visible. To create this space, Latta and Eckhaus worked with a bicoastal group of artists to design the shelves, hooks, mirrors, and seating that populate the space, creating something akin to a group exhibition, albeit one in which all of the objects maintain their function. The resulting aesthetic is ad hoc meets controlled precision. Torey Thornton’s sound system–equipped cardboard bench is placed near Sophie Stone’s sculptural rug assembled from rope, an IKEA mat, and found carpets. Annabeth Marks’s clothing rack is doubled by another parallel bar installed high above it that supports a large, unstretched abstract painting, drawing equivalence between different kinds of supports, a structural and conceptual framework to hold up painting and fashion.

Possessed concludes in a darkened room resembling a security office, with a grid of flat screens displaying closed-circuit footage from various retailers that carry the Eckhaus Latta label as well as from the adjacent retail environment. The silent videos offer banal shots of stores, their wares, and shoppers, acknowledging the ubiquitous tracking and surveillance that is part of consumerism, and revealing its dull visage. Unlike the high-gloss, attention-grabbing photographs at the beginning of the installation, the CCTV material has little flair. It is imagery that was never intended for public consumption. Rather, it is workaday footage for the shopkeepers and security officers who track shoppers and the products—not just to prevent theft but also to collect information on the habits of their clientele. The inclusion of this surveillance room offers a different perspective on the rest of the installation. Having reached a dead end, viewers must return the way they entered, revisiting the retail environment as well as the fashion photographs. Suddenly, it clicks that the cameras trained on a person can include both the fashion photographer’s lens and the unflinching gaze of surveillance. As shoppers covet new pairs of jeans, companies are swarming to the metadata of mass consumption.

For the Eckhaus Latta autumn/winter 2017 presentation, artist Collier Schorr walked the runway in a baggy, gray woolen sweater. Modeled after a dolman, a cape of Turkish origin, it sloped over her shoulders and draped loosely with elongated sleeves. Evoking 1990s slacker chic, the crocheted text on the garment snapped it back to the current moment. Reading “is this what you wanted” and absent of any punctuation, it proposed an ambiguous line for a time of uncertainty—a moment of political discord following a polarizing presidential campaign, of positive economic numbers amid individual hardship, and of innovative disruptions from Silicon Valley. Speaking about the garment, Latta explained, “I think of that one as a signifier for the wearer—the wearer is posing the question to the viewer, who would be the one passing judgement on the wearer.”Cronberg, 234.This one sweater anticipates the dynamic of Possessed—one of signals sent, received, interpreted, and potentially misunderstood. The knit dolman speaks to the desires of the wearer and the viewer, communications aimed in opposite directions, ready to get crossed and confused. Eckhaus Latta’s exhibition makes apparent the twinned conditions of selfie culture and tracking where consumers wittingly self-surveil ordinary acts in the attempt to fulfill the drive to consume and the desire for attention. The craving to be followed and liked becomes its own state of possession.