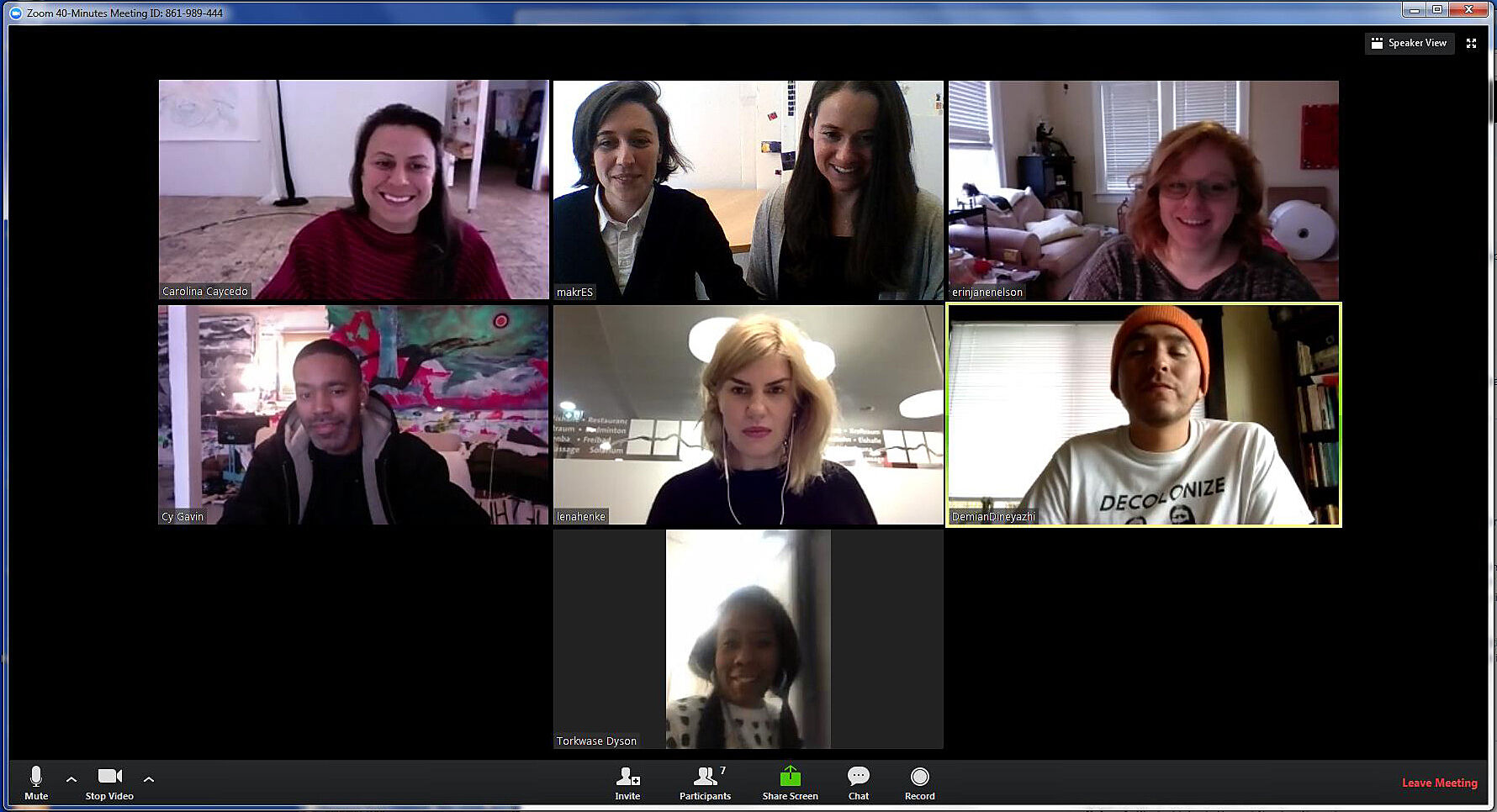

Between the Waters Roundtable

Between the Waters is about individual voices each speaking on a series of relationships that could be described as ecological: between the land, the forms and ways of life that exist on the land, and the systems of use or governance of the land. The artists whose work is included in the exhibition—Carolina Caycedo, Demian DinéYazhi´ with Ginger Dunhill, Torkwase Dyson, Cy Gavin, Lena Henke, and Erin Jane Nelson—assert that our personal beliefs and ideological values cannot be separated from the material reality of a changing Earth. As they describe in this roundtable discussion, they also resist the categorical terminology and methodologies of rational systems of thought, instead looking to emotion and spirituality as alternative methods to consider the relationship between the natural world and ourselves, in which we are neither in control nor completely eclipsed, neither anthropocentric nor post-human.

This idea of how the intimate, the visceral, and the experiential connect to broad environmental concerns—issues that are geographically disparate, historically distant, and often seemingly incomprehensible—was the impetus for the discussion with this group of artists. We asked them not just to focus solely on their own work, but also to reflect on each other’s work and question one another during the conversation. The topics vary widely, from queering the geological landscape, to rethinking class and race-based notions of self-care, to exploring the idea of spells and the fantastical. It also touches on a broader vocabulary, reconsidering terms such as “homeland” or the concept of “sustainability” versus “sustenance.” The concerns of these artists are not simply abstract ideas but are the historically rooted conditions shaping our present day, which are often slow-moving yet marginalizing, violent, damaging, and inescapable realities for many of us and for our planet.

Elisabeth Sherman: During our research and planning for this exhibition, terms like “environment,” the “natural” the “human” or the “social world” have appeared but also felt complicated, limiting, and imprecise. Because of that, we’ve tried to avoid those terms. We’re curious to lay the groundwork for a vocabulary in this conversation and to think about this kind of terminology at large.

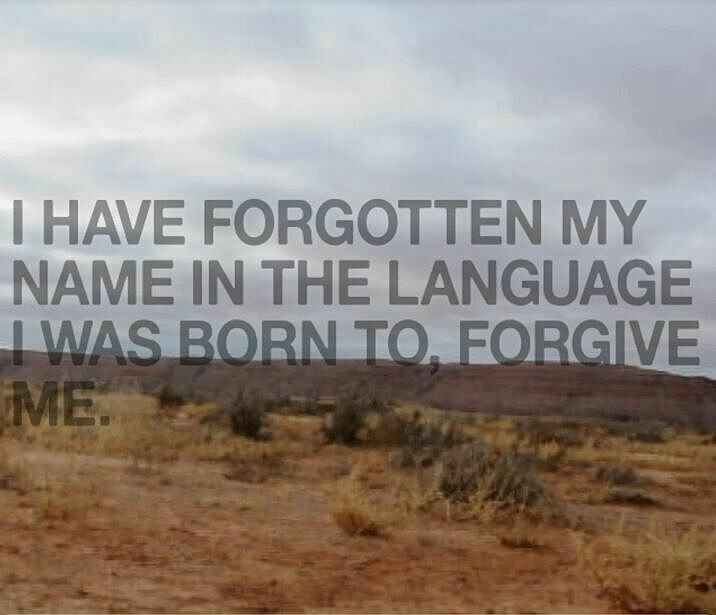

Demian DinéYazhi´: One of the works I’m showing is this older video called Rez Dog, Rez Dirt [2013]. It’s a single shot of the landscape, fixated on one scene, on my grandmother’s land on the Navajo Reservation in northeastern Arizona. When I made the video, my grandfather had just passed away; my grandmother was the only one living on their land. The whole video is, at the very least, about migration, Indigenous identity, and the ideas that surround your homeland.

Elisabeth: What’s interesting about the word "homeland" is that it’s a word that bridges two things that are often posited as separate. That’s one of the things you’re all interested in—those intersects of “home” and “land.”

Demian: In the video, there’s also a voiceover, "Spoken Words to Move a Consciousness," that I recited about moving between two different spaces: having one foot in my traditional, Indigenous homeland and the other foot in Western, assimilated culture, having moved from the reservation to Portland.

It’s about how the conversation of migration within the United States is inherently an Indigenous conversation—or at the very least needs to be grounded within this Indigenous context or thought process of continued migration. With the new work I’m making for the show, I’ll be collaborating with a friend, Ginger Dunnill. Ginger is mostly a sound artist who lives near Santa Fe. We’re compiling drone footage of different sections of the reservation—still talking about migration, but we were also really interested in this idea of burying white supremacy.

Erin Jane Nelson: I grew up in the American South but being a white woman in the South, thinking of this place fondly as a homeland, and thinking of it as part of my identity is so complicated.

In my work for the show, I’ve been documenting various barrier islands along the southeast coast, because I feel like it’s this place where European colonialism or racist white supremacy is being consumed by the ocean—being swallowed up by the climate change that its hubris has put in motion. Since many of the historical markers and monuments and burial grounds have been steadily eroding into the ocean, photographing there has been this way of documenting the death of the father and the demise of a homelands. How can I identify with the culture, but also be critical of it or try to untangle the complicated history of the region?

Carolina Caycedo: For me, it’s been useful to understand that there’s always a contradiction, and how we live better with that. I guess [with] all of us working in a kind of environmental consciousness, there’s also a contradiction of artists in whatever material we’re using in the production of stuff. What I was seeing is—perhaps we’re not artists proposing solutions but more open to different perspectives for the discussion, to try to understand.

In a recent show, there was a collage I made that said, "Sustainable, my ass." This is a word I have started to hate—“sustainability.” It’s a word that’s co-opted by greenwashing and green imperialism to make us feel better about modes of production and consumption that are not sustainable and never will be. I prefer the word "sustenance" for my work. It has more to do with support and nurturing.

Lena Henke: I see myself in the same mold a little bit. “Culture” and “nature” are equal parts for me. Therefore I’m interested in impact on the environment. Especially going over to the body, which I would probably translate into something that I would call a sculpture, or special materials I would then use. On the broader scale, I was thinking about terminology on how to describe my work. I think I'm interested in some kind of more interchangeable landscapes, where the relationship between the viewer and the physical foundation of urbanism becomes visible for the viewer then. I hope that my sculptures will draw some kind of attention or question the nature of how they exist in space.

Erin: I totally agree with you. I feel like the common thing between “sustainability” and this neoliberal idea of “environmentalism” is the hierarchy of the human over the land—with a disregard for what other human bodies or other bodies have been on the land beforehand. It’s all so focused on forward-thinking without any kind of reckoning with the literal decay that’s in the ground under their feet. It’s all about “sustaining” that dominant way of thinking about the land without unsettling the dirt.

Torkwase Dyson: I think I want to pick up on this idea, the language around sustainability in homeland. One of my concerns about the word sustainability is that you can sustain a lot of things, right? You can sustain a constant, uneven development. You can sustain a status of invisibility. You can sustain these things. This has happened because of colonialism. It's happening further because of the way in which climate change has been situated inside this larger breadth of problem called global warming.

Demian: To go on from what we’re both saying, about terms like “environment,” “nature,” and “eco-sustainability”—all of these are Western, settler, colonial constructs. The way nature has been built upon and settled in the New World—and has situated ourselves against nature—is emblematic of all these European heritages that were about erasing the people that were indigenous to this region. You have painters coming in and painting beautiful landscapes that were advertisements for kings and queens to give funding to conquistadors and whatnot to come into the New World and dismantle it in this very violent way.

Elisabeth: I think that that’s the very reason we wanted to start with this question about terminology. Those are the things implicit in so many of these words. The struggle we’re having in trying to articulate some of the ideas is that the existing language feels inadequate and limited and comes from a very specific kind of history—mainly western, capitalist, colonialist history—so how to address some of these things without relying on terms that have that history.

Margaret Kross: That’s one of the things all of you do in your work: while you don’t propose a different language or a new set of terms, you question our learned vocabulary for talking about the environment and propose a way of making something tangible that is otherwise invisible—be it the retrieval of certain perspectives that had been erased or the burial of colonial histories that persist today. This theme of erasure or invisibility is something that comes up in many of your works for the show. Could you speak to that idea a little more?

Carolina: I was reading Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, by Rob Nixon, and he talks about the displacement of different communities. He’s proposing the idea of an unimagined community. Before erasing a displacement [of people], first you have to erase some of the popular consciousness, which is also something that happens during colonialism.

You have this imagined blank map where, supposedly, no one lives, so you can just settle and build and do whatever. There’s a similar process happening under contemporary extractivism, which is an unimagining of the people who live there. Not only Indigenous populations are being affected but also rural communities. It could be helpful to think about the processes of unimagining a community or a group of people and how our work can maybe bring those people to the imagination of the public again.

Lena: I really like what you just said. I’m thinking about fantasies a lot, and what you were just saying about Nixon reminded me of what Robert Moses did in New York. I’m going to be showing a series of ceramics in the exhibition that are all about a time in the 1950s when Robert Moses became very present by building many highways. To do that he had to make room first, so he evicted many families for ghetto housing units, promising them a new infrastructure they were never given later. The ceramic totems, shaped like deformed horse hooves, are hybrids between dollhouses and architectural buildings you see in New York now.

Carolina: One of the works [I’ll be showing] is a video, This is Not Water [2015]. The format of the landscape has taught us to look at nature in a certain form. It’s that format that separates the viewer from the environment. My subject matter is freshwater rivers. This particular video aims to unlearn how [we think] a landscape should look, so in the video I experiment with turning the camera around—also playing with the footage on the editing table, unlearning and subverting that colonial idea of landscape.

I wanted a more spiritual interaction with the body of water I was filming, to let the water talk to me and imagine what she or he was thinking—what they were saying and how they wanted to be portrayed. I think it’s a portrait of that cascade, basically. I guess it has to do with my self-process of decolonization and unlearning—also, acknowledging the role of art in the gaze, acknowledging that gaze of the colonized.

Elisabeth: I’m really interested in these ideas of unlearning and fantasy, and how a number of you are interested in either projecting futures or imagining pasts, and the capacity of imagination or fantasy to create realities that are so different from the ones being lived.

Erin: It’s tricky for me because literature and the supernatural are such a big influence, but because I am of a colonizing race, I feel like my projections of fantasies and desires are really dangerous. Because that’s what colonialism was all about, right? I am inclined to depend on my own subjectivity, but I try to be as much in concert with other sources . . . using my imagination and speculation and contending with histories—or what these would be if there wasn’t such violent white supremacy in the history of the United States.

One of the things I’m working against is this kind of John Hume or René Descartes relationship of mind over body, or “logical” knowledge over emotion or sensorial or lore-based knowledge. In the South, there’s so much history of lore and narrative and fiction and the religious. I guess it’s that aspect that I feel is really charged and rich for unlearning or trying to recast a new collaborative understanding of these histories—but doing so with care so that it isn’t just about my desires.

Elisabeth: One of the things that also ties all of you together, is your own subjectivity and addressing these extraordinarily broad issues and ideas them through the personal and the particular.

Cy Gavin: My parents are actually both from colonies. My mom is from Puerto Rico; my dad is from Bermuda. Why I’ve been gravitating toward Bermuda and digging through that history and the current state of affairs there now is because it does not have a precolonial history. It was not inhabited before 1609. Bermuda is on top of a volcano [long extinct], and it’s small and not hospitable for crops, so it resisted human occupation for a long time. Seeing how it developed from a place that only had something like fifteen native plants to become a test ground for all the things that took root in the United States and in South America has been very interesting, but also manageable. There isn’t that preexisting question of "Who owns that land?" or "Who has right to the land?" It was itself—anticolonial. It’s an interesting place to look at how hegemonies come and go.

What’s particularly interesting to me about Bermuda is its role in the burgeoning industry of tourism to places that are subtropical or tropical. I know that that’s entirely shaped their culture as it stands now because it’s driven all of the economy, which is something that everyone participates in irrespective of race and class. There’s this feeling that you support the economy by whatever means possible because it is such a small place. There isn’t really an industry that’s based in Bermuda. That also means that people had to change their relationship, psychologically, with the space, as it allows them to survive.

With the establishment of the tourist industry of the 1920s, ships—mostly from United States—would come, and those on board would throw coins into the water while local people would dive and retrieve the coins as a reward for their efforts. If you were a local person, how can you regard that space as pleasurable now? It is, in your mind, crystallized into a work space, or a place where you are treated like an animal retrieving something for an over-lording class. Being such a small place, those accommodations that have happened in people’s minds to allow them to survive also create an industry that allows them to free themselves.

Erin: The comments about tourism have been really interesting. What Cy was saying about Bermuda resonates because along the coast where I’ve been making work for the show, there’s such a tourist industry around extreme affluence. There is tourism in Georgia about where [British colonizer James] Oglethorpe landed and where this first European fort was—all these public monuments and memorials. It’s really problematic because, often, these monuments are built on native burial lands. What I’ve been trying to do is to use narrative, crafts, photography, and being present in these sites to understand them even though it feels a bit like tourism. . . Carolina, you were talking about being spiritually present with the water; I’m trying to use less traditional ways of understanding or recording or documenting the land, in order to make visible those invisible histories.

Torkwase: The reason I make the work that I make is to understand a systemic order around state changes to our planet. What that means is, as humans interact with, use, or participate with our natural environment, how do those things, then, support our lives? How do we think about energy and resources that supply our different habits and needs? I’m interested in understanding how that looks and in using, in my work, a form where I begin to unlearn these things.

For example, I’m unsure how engineers determine what kind of extraction happens based on the different geographical sites they’re interested in extracting from. All of this exploitation is not uniform. Development is not uniform. Each has a particular motion as it moves forward. How are scientists learning about these places that are already overdeveloped? How are they thinking about geographies that have a history of underdevelopment? How do I think about, in my artwork, the state of change through different geographies simultaneously in this macro way? I enter it through a deeply personal, overwhelming concern about everybody, all the time, always.

Carolina: Scientists have been presenting hydroelectricity as a clean energy, for example, for ages. Finally, in the last decade or so, a number of grassroots movements and also scientists who, perhaps before, were proponents for dam construction have realized the damage it poses, blocking the river flow and displacing people. The fact that they’re extracting clean water or air collaterally with those kilos of minerals means that they’re taking away from the humans in that territory the possibility of existing and functioning as healthy individuals.

Jumping back to terminology, “natural resources,” for example, is something I always try to challenge as a term. Again, it puts the human in the center of the action and puts everything in a bag for us to extract, to study as scientists. Maybe “commonness” or “common goods” is a better term. Family members and a lot of Indigenous people I know use the ancestral names for rivers or mountains. Sometimes, it’s just “grandfather,” in a specific Indigenous language, or “mother,” “uncle,” or “brother.” I like to understand that as an extension of yourself.

Demian: My work for the show came out of a horrible anxiety attack in New York and feeling like I had no space to feel a connection to the land. And being so upset with the fact that this entire region was Lenni Lenape territory, not even territory but land that was managed. Again, this is a question of terminology. I hate these terms “territory” and “land management.” People took care of that land, the Lenni Lenape, and there is no connection for any New Yorker to that original history. I was thinking about Agnes Denes’s work—the giant wheatfields [she planted] in the lower part of Manhattan—I was just thinking, what it would be. And all these images of gravesites at Wounded Knee, these mass graves for Indigenous people, just kept popping into my head.

I was also thinking about these images in terms of white supremacy and how it’s all about burying Indigenous history as a way to create a new history. In real life, in my traditions as an Indigenous Diné person, a lot of really horrible shit that happened came out of extraction throughout the Southwest. There was uranium extraction, coal extraction. There are water rights issues. I was trying to think of it in terms of being so upset, having this really horrible anxiety attack. When I was initially contacted about having work in the show, I wanted to have conversations about the concept of a city, what that means, the concept of belonging, this romanticization of the city, and how people who had their ashes scattered across an entire city have no ties to that region.

The work itself is about the concept of digging. It’s about the concept of doing away with something that is in the process of already being removed. Even though white supremacy is very much alive and active right now, I don’t think in hopefully like a century from now that will be the case, if we’re still around. Or if we are the ancestors of people who are going to do other, future world building and think outside the binary of colonial and Indigenous or male and female. I know Carolina just mentioned these terminologies, “father” sky or the “grandfather” or “grandmothers” of a region. I think it’s also really interesting to think of this world as more of this trans, queer body. A lot of the work that Ginger and I are doing is bringing some of that up and challenging that terminology. I think of my work more as a framework for heading toward language that is already on its way to being fully formed. A lot of the trans and queer community has this language. A lot of intersectional communities are building upon this language. The work we’re making is more in conversation with that.

Carolina: Can you tell us more about Ginger’s work?

Demian: We’ve been working together for a while. We had the opportunity to work together this past summer on this project called Nothing Is Natural that was talking about environmental racism, forced extraction, and violence against women—trying to make the connection between violence against women and violence against the earth. We were also interested in raising this question about whose responsibility it is to speak up about the land. If we see something going on, we have a responsibility to be calling attention to it.

Carolina: Maybe this is a broad question and I don’t want to throw you in the water. You can respond it or not or we can get back to it later. I was very interested also as maybe the only queer voice of the group.

Cy: [laughs]

Torkwase: No, don’t assume that. [laughs]

[Laughter]

Carolina: Sorry, one of the queer voices in the group. This question is for whoever identifies as a queer voice. How can we start thinking outside the box of “grandmother,” “grandfather,” and this kind of heteronormativity? What is your approach to queer environmentalism, or what do you suggest this may be?

Erin: My octopus that is included in the exhibition came out of this speculative sci-fi narrative I wrote about how they model decentralized, shape-shifting, perhaps ungendered, form underwater. And how they can maybe be our models or guides as queer aliens in this new watery realm that’s going to consume all land masses in the next hundred years. I see the octopus as a feminist queer symbol in the way that its bodily structure and the way it exists in the world is extremely sensitive and fluid and non-rectilinear. It has a completely decentralized nervous system.

The other thing I want to mention with regard to anxiety and the institution is that I think probably all of us are anxious people, I would guess [laughs]. So many [of us] live outside of New York and are representing regions or histories or identity positions through our work. It makes me feel very anxious. I think the role of the institution and being in that institution is about letting your own subjectivity be a brave guide for others to start accessing their own empathy and to make a space of communion for environmental anxiety, which I feel is becoming so much more pervasive. I lived in California for years before moving back to Georgia. I had to leave because I had so much environmental anxiety.

Elisabeth: I’m glad you brought up anxiety again and talking about it in the communal sense. Right now every other headline is about anxiety. We’re all living in the age of anxiety. And I think many deal with personal anxiety that calibrates itself against a more global anxiety, but also is separate from it.

Erin: I think the other kind of powerful or maybe queer or less heteronormative or patriarchal way of thinking about anxiety is that, because of mental illness and PTSD, I am considered non-able-bodied. Other people feel this too. It’s this invisible way of not being able-bodied. Acknowledging anxiety and mental states is something that comes out of queer and feminist art as a subject matter for art making. It’s a rich political tool for advocating for a broader view of self-care and inclusion and supporting each other personally.

Demian: But that’s also a very Western thing. We live in a community, in a country where we can afford to talk about our anxiety and practice self-care. Nobody on the rez is having those conversations, or able to take care of themselves, or recognize bad patterns, or even talk about ancestral trauma.

Erin: The introduction of self-care comes out of intersectional feminism. It was invented by Black women to deal with trauma.

Torkwase: Kimberlé Crenshaw [the scholar of critical race theory].

Erin: Yeah. Although it maybe has this contemporary iteration similar to green living and sustainability in this neoliberal Western thing . . .

Torkwase: I want to say something about the idea of care and the way we are talking about care right now and putting it in another binary between Western and other. I think about my own historical identity and about hair braiding as care. I think about ritual as care. The word “care” gets us into these binaries that are not discursive in relationship to class. As you talked about this idea of intersectionality—this term that Kimberlé Crenshaw sort of canonized—to make a space where simultaneity can happen, so that there is no you, me, that, they, or fixity. When I think about what it means to exist as a queer-bodied woman, it’s to say, well, how do I think about, again, simultaneity? How can I use my own brain capacity to be able to make space for not only the differences within social sciences but the differences within physical sciences?

I am really interested in how my own neurological system adapts to the multiple folds of what it means to go toward a freedom. What does it mean to have a neurological system that’s different from person to person? As we talk about “care,” it’s actually something that colonization has really disrupted. The way we look at “them,” we don’t even recognize when people of color are caring for ourselves in different ways. I would reject any idea that we couldn’t locate what we understand completely as caring for each other.

Demian: That’s something that happens in the community I’m a part of—"I can’t afford to take care of myself"—not realizing that there are various forms of self-care that have no ties to capitalism. You touched [on] a lot of that.

Lena: I was just thinking about “body” and then “materiality.” It reminded me of my Female Fatigue series and the way I was exploring this kind of intimacy with space, particularly in New York. You have these unique, dense urban centers traversed on foot. I abstracted some feminine nudes molded out of sand and put them on top of metal structures that directly recall facades of buildings and institutions. I thought most about the art scene in the ’70s in New York City, recalling specific spaces where artists would hang out. I was thinking about vulnerability in working with sand, molding female bodies in sand. The woman appears to melt—fatigued—into the urban block. To [take it] a little bit further, these sculptures can get remolded by anybody. I created my own readymade, in a way. These pieces could go to somebody—he could have my body and make it as often as he wants. And it would be very ephemeral.

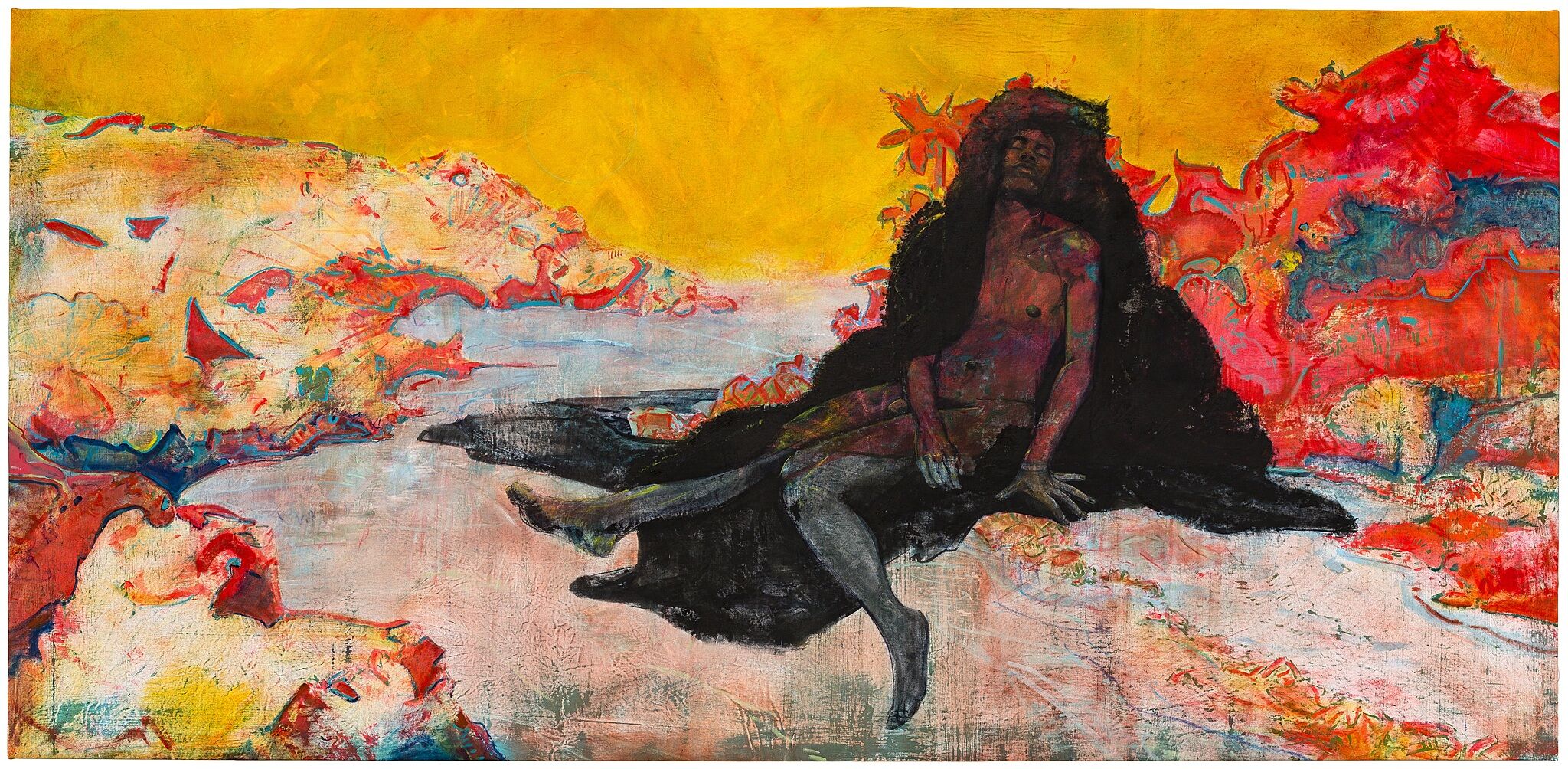

Margaret: The relationship between material and body is interesting. You’re talking about sand and body. I’m also thinking about Cy’s work here. Cy, do you want to take on some of these questions about the relationship between emotion, anxiety, what happens to our internal lives, and then how that relates to the physical experience of the material world, and your processes in the studio?

Cy: My experience of Bermuda was reactionary, in some way, to my religious upbringing, which was hyper-Christian, and becoming disabused of feeling like I’m something made in God’s image, and feeling that I’m of the environment. I felt very conscious of the fact that a lot of people have passed on that land. It is literally composed of people that came before in times when they wouldn’t have been given a tombstone in what we consider, in the West, a proper burial.

The beaches that people luxuriate on are literally composed of my ancestors. I do therefore feel that I am the ghost that haunts me. I don’t feel a huge difference between myself and the land when I am there. I think it’s also something that has to do with sand, that it’s a composite. The white of the white sandy beaches in Bermuda comes from the excretions of a parrotfish that eats the coral reef. It is extremely cyclical. My feeling of being part of that space is something that I’m trying to enact in a painting. That has governed my inclusion of things like sand in paintings. I create a sort of re-enacting of this space.

Cy: The yellow paint comes from urea of a cow in India. The black is from charred fish bones. The material substrate is cotton. It’s [all] a reconfiguration of a limited number of periodic elements that compose everything, including us. It’s something I think about in relationship to the people who were there, and here, and [to] myself. Our history as human creatures is traceable, and I think that can be contentious because of various belief systems and creation myths. I find the idea of obliterating rights to land to be encouraging. I don’t feel that people have a right to land; people are an animal like any other. There’s an interconnectedness that can’t be ignored and that I try to inhabit and use in my work. That frames my feelings about politics, which governs my existence and my access and my ability to survive in the conditions that I’ve inherited by being born in the time that I was—how that works its way into every single facet of existence is interesting to me. If it’s activism, it’s not just linked to Bermuda or even the United States, but [to] thinking about humanity.

I started this last year to work through my feelings about all that. If it is our representation of history, first of all, it’s a contested history and not to be taken at face value. There’s a danger in representing “real,” whatever that is. It ends up being used as proof of suffering for other people and not just artwork, but something that is still a part of some kind of oppressive structure where you aren’t just a person, you are a person who’s becoming an emissary for all these other people within a certain designated group that is to me arbitrary. It isn’t meaningless, but I think that those bounds are man-made, recent, and still divisive in a way that I don’t like.

Margaret: How have others engaged with material and form and figuration in relationship to the sociopolitical undercurrents we’ve discussed? One of the organizing parameters for this show was that all of you have a commitment to a rigorous studio-based practice, rather than social practice or conceptual work. Could you address this a bit?

Lena: The bronze sculpture I will show looks like a relief of the Manhattan skyline filled with all the things that have become iconic to me over the [past] five years. I see it as a kind of blueprint or “mapping” of myself. The city becomes the studio. I’ve been visiting a lot of parks and landscape gardens—the age-old drama of public space. I’m very interested that one individual built this kind of dream or fantasy. Some of my favorites have been built by Sir Edward James and his garden in Mexico, or [Brazilian landscape artist] Roberto Burle Marx, or [Mexican architect] Luis Barragán, who built everything from the scale of a horse. I like to step into someone’s world view, or their very own psycho-sphere, using their same toolset but then organizing it for myself to make a home for my own work in a way. I can see this in Carolina’s work, right?

Carolina: Yeah, the material, the natural reality of the nets. I’m showing a series of handmade fishing nets—some of them have been used, some of them are new—that speak about a specific gesture that fishermen and -women have, how they interact with the river, from the weaving of the net to throwing the net over and over again for their sustenance.

With the nets, I feel a shift in my process, to really finding pleasure in working with the material and understanding that each of the nets already has so much history from the person who made it. I’m interested in places where people come together—interactions, compiling stories, listening to people. Working with the nets has given me pleasure in working with material like I’ve never had before—understanding the flexibility and possibility of the nets as structures: to apply color, to stretch, to bunch things, to hang things.

As far as what the work is about: The net as a structure is the opposite of what a dam is. A dam is this huge, monumental, corporate-scale, machine-made thing that breaks a river in two, while the net is human scale, a handmade series of knots. It’s beautiful, because in Spanish the name of the net is atarraya, which comes from an Arab verb, to throw. Also, if you divide the word it means atar (to knot) and raya (line), to tie a line, which is basically making knots. The nets, for me, have become a map of how we can function better as a collective, as a succession of knots.

Margaret: I want to turn to those of you who don’t work as much with concrete materials or in sculpture. How can we talk about abstraction as a strategy in this conversation, not just geometric abstraction but in terms of poetry or abstracting ideas?

Torkwase: I’ll say, [by] listening to the knot as a metaphor—a physical action, the net as what I would call a performer, and a performer that is constantly asking for interactivity from multiple publics. I want to use the net as a metaphor to think about abstraction as a tool because it both adds boundaries and takes boundaries away. When I think about your work, Carolina, what does it mean to be in a space where the land is being abstracted because of extraction? What does it mean to pile on a system of propaganda, of language, of specialized knowledge, of disappearance? All of those layers, I would argue, are abstraction that [is] about distancing and layering, so that things are completely opaque.

The net, for me, becomes a mound of things you can’t really see completely through, but you can see beyond the first layer. Then when you pull that net out, it becomes not only something you can see absolutely through, but it allows other participatory acts. How do we make things with our bodies that include other kind of socialities simultaneously? That’s how I think about abstraction as a tool to think through things in a way that’s plural, depending on who has the tool [laughs].

Erin: In my mind, the original Modernist abstraction, at least in the history of Westernized American art, is the quilt. Certainly quilting, weaving, and textiles are ubiquitous across all classes, races, and cultures as historically feminized practices that record histories and also provide a function, but are based in abstraction. That’s where all my artistic birth comes from, quilt making. My textile pieces in the show are a very evolved form of quilts, as a form of abstraction that has these multivalent functions. Using materials that provide different levels of opacity, hiding, safety, and protection is meant to evoke certain positions of vulnerability, guarded information, or very raw and tender information. I also come out of photography history and the history of image making in relationship to cultural consciousness. Materiality in my process has always been about destroying the rectilinearity of a fixed printed image, which is evident in both the ceramics and textiles.

Torkwase: I want to make a case for not leaving a trace as a radical practice. I’m thinking about the ways in which, historically, the hand or the gesture leaves a residue of that hand or movement. As we transverse these geographies based on political, environmental, or systemic oppression, people have to move through space and toward freedoms without leaving a trace. What does it mean to have the skill of not leaving a trace of a hand, or a scent, or a footprint?

Margaret: That’s so interesting and immediately makes me think of this work that, Demian, you’ve talked about in the past, and is representative of a more sculptural part of your practice than the diaristic videos you’ll be showing. I don’t want to call it the anti-earthwork piece, but do you want to talk a little bit about the gesture of “giving the earth back”?

Demian: There’s a piece I had shown at the Portland Art Museum. I had driven home and removed some dirt from my maternal grandparents’ land on the reservation. A lot of ceremony has taken place on that land from Indigenous Diné traditions. Most of my sisters have had their puberty ceremony [there]. You just dig into the earth, bake a cake [from the earth], and then you leave the pit open after you’re done with it; the earth eventually fills in by itself. I had removed some land that wasn’t too far from there [and] had driven it all the way to Portland. Part of that piece was about removing the earth, traveling with it, dedication to community, and this continued story of migration. Then the other part of it was about bringing the earth back and putting it back on the land.

That was about, again, actively devoting yourself to your community and those issues. Also, recognizing the importance of Indigenous Diné ceremony and the fact that, even though these puberty ceremonies had taken place for four days at a time over twenty years ago, ceremony is a continual thing. The land is still continually doing its magic and working with the people as long as you’re in good standing. For the Diné, it’s like staying in this state of Hózhó, which is maintaining a balance with yourself and with nature. It’s a concept of being that is indescribable through the English language.

Margaret: You said something about magic, and I wondered if you could elaborate on that a bit because it’s something that comes up for a number of you in different ways. Erin, we’ve talked about this in terms of the relationship between technology and magic, and why ideas of the supernatural are resurfacing now. Then, Carolina, we’ve talked about magic as a way of bringing life back to the colonized land.

Erin: My grandfather was a very early computer technologist in the ’60s and ’70s, especially with early computer graphics. My entire life I’ve been surrounded with an fettered enthusiasm for technology, but I’ve been trying to balk against the trend toward “techocracy”—this rule of enormous tech companies and algorithms sorting over our lives and as the greatest achievement of humankind. In past projects a lot of my work has dealt with the ways technology actually undoes a lot of the course of Western, expansionist, Cartesian, logic-based arguments and opens up the world to a broader connectivity. It makes possible this imagination of magic and reanimation, so that a piece of glass can become a portal, or a tree is speaking.

It hearkens back to this more folkloric or mystical, magical possibility that isn’t so fixed within boundaries and what is or isn’t living, or is or isn’t animal, or is or isn’t human. That’s the way that I found to balk this inheritance of the tech overlord of my family—trying to turn technology on its head and make it something that isn’t about this hyper-commercialized Silicon Valley-space that’s decidedly super male and super capitalist, but is more akin to some of the early technologists. I’m thinking of Jaron Lanier who invented the term “virtual reality.” His approach is all about the magical possibilities of technology, a more utopian view of how it might be a tool for accessing magic and freedom, [and] less like the one we’ve seen of social stratification, inequality, surveillance, and domination. Side note: He’s also really interested in octopuses.

Carolina: Yeah, I think [this idea of magic] has to do with what is happening in Latin America as a whole in terms of environmental resistance. There have been strong movements from the Indigenous communities, from the rural communities, Mestizo communities, Afro communities, too, and the more urban environmentalism. Many bring to that mix rituality, and the understanding that rivers, mountains, stones, trees are socially active agents. Maybe the fact that the waterfall was talking to me could be considered magic by some, but for others it’s natural. It happens all the time that a tree speaks, that a stone is speaking to you, or that the wind brings a song and inspires you to do something. It’s not even really magical; it’s always been there. Of course, the structures of colonial form and understanding of nature have tried to erase those, [to] plug our ears and close our eyes to those happenings.

I guess in a more institutional way it manifests that, for example, in Ecuador, you have the mother earth, the fact the mother has constitutional rights, is the subject of rights. In Colombia, the Atrato River was granted legal rights last year too. Those are more institutional manifestations of that kind of magic. When I do fieldwork, I spend time, work, fish, film, gather stories, interview people. I think there’s also a spiritual fieldwork happening, because you don’t only collect objects, you’re collecting sensations. You’re connecting to people, too, or to that specific river or that specific bend of the river. I would come back to that word “spirituality” and allow the work to exist in that realm, too. To exist in the material reality, to exist in the political reality, to exist in the spiritual reality.

I do think the nets function as little hechizos, or spells. There’s this intuitive process of putting things together. I don’t know, Torkwase, maybe you have a similar approach? A lot of the works I see of yours are the paintings, or even Erin’s fabric pieces. I feel they have a connection to my work in the sense [that] they become little spells—visual spells to protect, to drive away the unwanted, to hide what you were saying, or to frame again. I think there is potential in thinking about art as visual spells, visual magic, or visual activism, too.

Erin: I love the word “spells.” I haven’t thought about that [before], but I always think of digestion and recipes. Your word “spells” made me think of the word “recipe,” and [the] relationship of food and the body. I use a lot of haptic, sensory things in my work because understanding embodiment and place requires more than just the visual. Inevitably, these survivalist, protective things, like the quality of food, recipes, spells, or whatever they may be—they’re the guts.

Carolina: The black paintings of Torkwase seem like black mirrors—this idea that you can reflect yourself on this black surface, and then become black suddenly. Or it’s like a portal into the darker side or what’s been obscured. [I’m] thinking that mirrors also play an important role in all kinds of magic and spells.

Torkwase: When people look at the work they think about a kind of black, but most are actually red, black, and green. The shade is from a practice I have come to understand by diving in so many parts of the oceans around the world and understanding how light changes underwater, refraction happens, shade happens, and tint happens. For me, it’s about where the physical sciences meet the social sciences, where the understandable and the measurable meet the visceral. My work is trying to parse all those things while dealing with the visceral experience I have. I’ll say “visceral” because that’s what I’m interested in in my surface. Abstraction can bring you very close up and personal to see a rendering of a site or a resource that you then understand has been rendered outside of you.

Abstraction can create a distance that allows you to comprehend a systemic logic—how it has been controlled and designed outside your input. To be a part of an environment of global warming that has nothing to do with my decisions in terms of the macro is alarming. My interest is in working in these established realms of looking: How do I get closer to that through this form which I’m using, abstraction? My image building is very much around the diagrammatic and using drawing as a way to know these practices that are out of my hands—to talk about what it means to be on a planet where the water is constantly in a state of change, and then making paintings that have to do with color and the change of light.

I’m trying to use painting as a way to get to that kind of knowing. Seeing them in person, I hope you feel the same way [laughs]. I hope that you feel that it can maybe be a spell or something that is spiritual. I understand the Whitney to be a micro-lens in which I get to think about movement and motion. I'll go back to Carolina's point and I think Rob Nixon's point: what does it mean to think about slow motion? I tried to make paintings, and put them on the walls of institutions, where people think about time and movement and liquidity and state change based on my surfaces.

Lena: I’m very interested in movement as well. That was my question for you both, guys, Carolina and Torkwase. I’m working with the possibility of some kind of art that prods us into consciousness of the framework that defines our experiences of the artwork itself. For me the idea was the validation of a monument. I was thinking about the museum as a platform, or, as Rosalind Krauss has argued, the museum is a substitute for a public square and not simply neutral. That’s more the way I see my work. Carolina and Torkwase, how do you translate your ideas directly into the institution? How do you see the walls of the institution holding your work?

Torkwase: I think that’s a really fantastic question because we’re working in a compartment of an institution, post-Robert Moses. We’re working in the wake of Robert Moses, within the Whitney itself, navigating a city that, by his design, employed a kind of forced movement. Is it a colonization within a colonized space within a colonized space? I tried to try to make objects that are themselves a part of the state change and a part of slow looking as much as possible, where the institution allows itself to have conversations about “What does it mean to be among the human race where we’re constantly in a moment of state changes that happen over different time periods and with different motions?”

Elisabeth: Yes. There’s this expectation in an institutional space that seems to limit the body’s possibilities to many viewers. Some of you try to change or inflect that viewing experience within the space of the exhibition. Ultimately, it’s always going to be the kind of bounded, limited forum that it is because of the way it’s been previously transcribed—broadly, but also within the Whitney as a specific institution and as the context for this show.

Carolina: This also delves into that activism question. It was super hard for me to carve my way into the art world as a Mestiza woman, so I want to claim that identity as an artist. I’m not an activist. I participate in activism through art making, through the construction and the deconstruction of images. That’s what I know to do. To make art, for me, is the way that I’m a citizen, too. It’s the way I participate and build society. As an artist, I insert myself in that institutional space, understanding that a museum is a space where pressing issues of society have to be discussed. It doesn’t happen a lot [laughs], but it should.

I’d like to think that with my work, the presence of my work or, for example, the presence of this exhibition in a place like Whitney, some conversations about climate change and climate collapse can start to happen among visitors or women in institutions. For me, a museum is a good space for a real political arena, or a real community. But touching on what Torkwase was saying before, the solution for this collapse is not going to be a modernistic structure that has to be implanted and is the same everywhere. The solution for the Magdalena River is different from the solution we need in California for the drought.

Demian: I don’t think any of these solutions are going to exist inside the Whitney or inside the institution. I see my engagement with the institution as an opportunity to have these conversations, but also to give voices to marginalized, underrepresented, or Indigenous communities. I went to the Whitney’s exhibition An Incomplete History of Protest [2017]. From what I could tell, there were two pieces by Indigenous artists. One was by Edgar Heap of Birds, and the other was by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Both of these pieces are not explicitly political. In the same ways that you’re showing through the Black Panther documentation, that you’re showing work by the Guerrilla Girls, which is largely exclusionary of indigenous women. I guess my engagement with the Whitney is more a way to add this indigenous context or narrative into the institution.

Elisabeth: That goes back to the question of art and activism, because what you’re challenging about the Protest exhibition is that those two contributions were not protesting in the same way as other things within that exhibition.

Torkwase: I think what’s interesting about our collective ideas is that, when I think about Cy’s ideas, for example—What does it mean to be a part of a land where your labor, your body, is a kind of odd natural resource? In the negative sense what you’re saying is that body then becomes a part of an identity of that land, that it’s exploited. I think there are all these different kinds of precariousness around the way we think about who gets to think about first-personhood, or about movement or belonging? How do we consider ways in which our beginnings and our histories and ontological memories are twisted—sometimes not only erased but nonexistent in a particular way? I’m interested in the way we connect, but also understanding the waters that are between us. How do we connect to those personally, in how we see ourselves belonging in those histories?