Teacher Guide:

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World

Nov 3, 2017

Welcome to the Whitney!

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, on view at the Museum through January 28, 2018. The exhibition highlights Durham's expansive practice, which spans sculpture, drawing, collage, photography, video, and performance.

This teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offers suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs Team

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World

"I feel fairly sure that I could address the entire world if only I had a place to stand." —Jimmie Durham, “The Ground Has Been Covered,” 1988

Jimmie Durham (b. 1940) has worked as a visual artist, activist, performer, essayist, and poet for more than forty-five years. One of the most inventive American artists working today, Durham has produced wryly political art over the last four decades. Using materials as varied as animal skulls, oil barrels, stone, and olive wood, he approaches his subjects with a potent blend of poetry and humor.

Durham started making art in the mid-1960s, leaving the United States to enroll at the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1969. There he worked primarily in performance and sculpture and became increasingly interested in the possibility of integrating art into public life. Focusing his attention on activism when he returned to the United States, Durham worked from 1974 to 1979 for the American Indian Movement (AIM), an advocacy group that addresses issues facing Native Americans. The influence of Durham’s activist work can be seen in his art in the years that followed when he began to explore the ways in which Eurocentric biases have impacted representations of Indigenous peoples.

An active participant in New York’s vibrant downtown artist community in the 1980s, Durham left in 1987, moving first to Mexico and then to a number of different countries in Europe. He has engaged deeply with the culture and history of each of his adopted homes, drawing on the local language, materials, and architecture to reframe larger political, historical, and philosophical questions. Throughout his travels, he has declared wherever he happens to be—whether Mexico City or Brussels, Marseille or Rome, Naples or Berlin—the “center of the world.” As he travels, Durham works with materials that evoke his local context. He pays close attention both to their physical properties, and to their political implications.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World is organized by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and curated by Anne Ellegood, senior curator, with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant. The Whitney’s presentation is organized by Elisabeth Sussman, Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography, and Laura Phipps, assistant curator, Whitney Museum of American Art.

More information:

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. We have included some selected images from the exhibition, along with relevant information that you may want to use before or after your Museum visit. You can print out the images or project them in your classroom.

Pre-visit Objectives:

- Introduce students to the artist Jimmie Durham and works in the exhibition.

- Examine themes students may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how Durham has used materials, humor, and irony in his work.

Jimmie DurhamTlunh Datsi, 1984

While living in New York City in the 1980s, Durham began making sculptures composed of wood, stone, and animal parts, including bones, skulls, fur, leather, feathers, and teeth, often in combination with manufactured objects. He experimented with new approaches to some of art’s oldest subjects, such as the honoring of the dead and the relationship between humans and animals. He also started investigating ideas that had become important to him during his years as an activist: the fluidity and complexity of identity, the violent histories of colonialism and nationalism, and the many stereotypes that plague Indigenous peoples. Durham thought of this work as a kind of collaboration with the animal itself―in this sculpture, a puma―a process of discovering how it felt to be dead, and interpreting those feelings through sculpture. Durham’s art often involves this kind of imaginative effort, almost a form of empathy with his materials. The title, Tlunh Datsi is the Cherokee name for puma, and this sculpture is one of several works that Durham made for a 1984 exhibition at the Alternative Museum, New York.

Artist as Observer:

Materials and Meaning

Jimmie Durham often makes sculpture out of materials that he finds and collects, such as glass from Venice, industrial machinery in New York City, or a fallen tree with bullets in it in France. To him, these things express the spirit of the places where he found them. He combines these objects and materials in surprising ways.

a. Ask your students to look closely at Tlunh Datsi, 1984. What materials and objects do they notice? Have students make a list of the items they recognize in this work. Where do they usually see these materials and objects? Ask them to describe places where they might find them. What associations, meaning, or personal connections do they have?

b. Ask each student to find an object or a material in the classroom. It could be natural or manmade, something in the room, in their pockets, or book bags... Ask them to continue their list with the classroom materials and objects. Discuss what they chose and why they selected those specific items.

c. Ask your students to look at other images in this guide. What do they recognize? Where do they think Durham found the materials and objects for these works?

d. For older students: tell them that Durham thought of Tlunh Datsi as a kind of collaboration with the animal (a puma) itself, a process of discovering how it felt to be dead, and interpreting those feelings through sculpture. Durham’s art often involves this kind of imaginative effort, almost a form of empathy with his materials.

Ask your students to divide into small groups. Have them imagine the sculpture from the puma’s point of view. What setting might it have existed in? What might its past experiences have been? What questions might they have for this animal? How do they think the animal might feel as part of this sculpture, based on the choices the artist made? In what ways can students empathize with the puma?

Have student groups write a collaborative poem, letter, monologue, dialogue, or short story about the puma. Ask students to present and discuss their writing. How did they interpret the work from the puma’s perspective?

Jimmie Durham

Malinche, 1988-92

Jimmie Durham

Cortez, 1991-92

Jimmie Durham

Malinche, 1988-92 and Cortez, 1991-92

When Durham originally made Malinche, he conceived her as a representation of Pocahontas, one of the mostly widely mythologized Native American historical figures. Three years later, he transformed her into an Indigenous Mexican woman who was given as a slave to Hernán Cortés, the sixteenth-century conquistador, by Mayan rulers and who became his interpreter and bore him a child. While Pocahontas is commonly depicted as a “civilized savage,” Malinche is often viewed as a traitor who played a role in the fall of the Aztec empire because of her relationship with Cortés and her perceived willful aiding of the Spanish colonizers despite the reality that neither woman had much say in her fate. When Durham transformed Pocahontas to Malinche, he created Cortez to sit alongside her. Part man, part machine, he serves as a metaphor for modernization ushered in by violence. Together these sculptures call attention to how historical facts can be altered to become myth, and the ways in which history is distorted by those with the power to write it. Durham commented about these works:

"I did want to show the unreality of the myth, of the idea. The unreality of what they call reality. I carved a more realistic looking foot and I had a piece of yucca cactus that just happened to look like a foot, so I stuck it on. Then, I made Cortez, but for a long time, he was just a face. I made many different layers that were all tinted differently, so then when I sand it down, it looks disgustingly like flesh, if flesh were dead and petrified. I wanted him to look monstrously bad and greedy, like he wanted Mexico." —Jimmie Durham

Jimmie Durham: Center of the World Audio Guide Stop for Malinche and Cortez

Artist as Storyteller:

Myths and Stereotypes

a. In small groups, ask your students to look closely at Durham’s sculptures of Malinche and Cortez then help each other pose like these figures. What attitude might each of these sculptures represent?

b. Use the resources below to give your students some background information about Malinche and Cortez and discuss how these characters have been stereotyped and mythologized:

NPR – "Despite Similarities, Pocahontas Gets Love, Malinche Gets Hate. Why?"

Bitch Media article about challenging Native America female stereotypes.

“Then, I made Cortez, but for a long time, he was just a face. I made many different layers that were all tinted differently, so then when I sand it down, it looks disgustingly like flesh, if flesh were dead and petrified. I wanted him to look monstrously bad and greedy, like he wanted Mexico." —Jimmie Durham

Whitney audio guide stop for Malinche and Cortes

Discuss how the materials and the pose that Durham chose for his sculpture of Cortez might express badness and greediness.

c. Ask your students to identify and discuss characters they are familiar with from popular culture who have been portrayed as “good” or “bad.” For example, “good” characters might be Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Storm, Cyborg, or The Flash. “Bad” characters might be Darth Vader, the Wicked Witch of the West, the Joker, Voldemort, or Sauron. What materials or objects would students use to depict one of these characters? Why?

Jimmie Durham

On Loan From the Museum of the American Indian, 1985

"I was struck by the idea, Museum of THE American Indian. It’s such a clumsy term. You wouldn’t say, Museum of the Italian. Museum of the Jew. Museum of the Black. It’s not nice to do that, is it? Then I said, that’s something to poke at. That’s something to play with." ―Jimmie Durham

Whitney audio guide stop for On Loan From the Museum of the American Indian

These objects, which Durham labeled “fake artifacts,” “scientifacts,” and “sociofacts,” come from On Loan from the Museum of the American Indian (1985), a pseudo-archival display like those found in natural history museums. The installation gathered together personal items, such as photographs of family members and a handprint made with Durham’s blood, and objects related to issues facing Native Americans, including land rights, common stereotypes of the “savage,” and the appropriation of cultural products and imagery. In Pocahontas’ Underwear, for example, Durham uses hyperbole to critique the way a complex figure’s important role in American history has been simplified and sexualized.

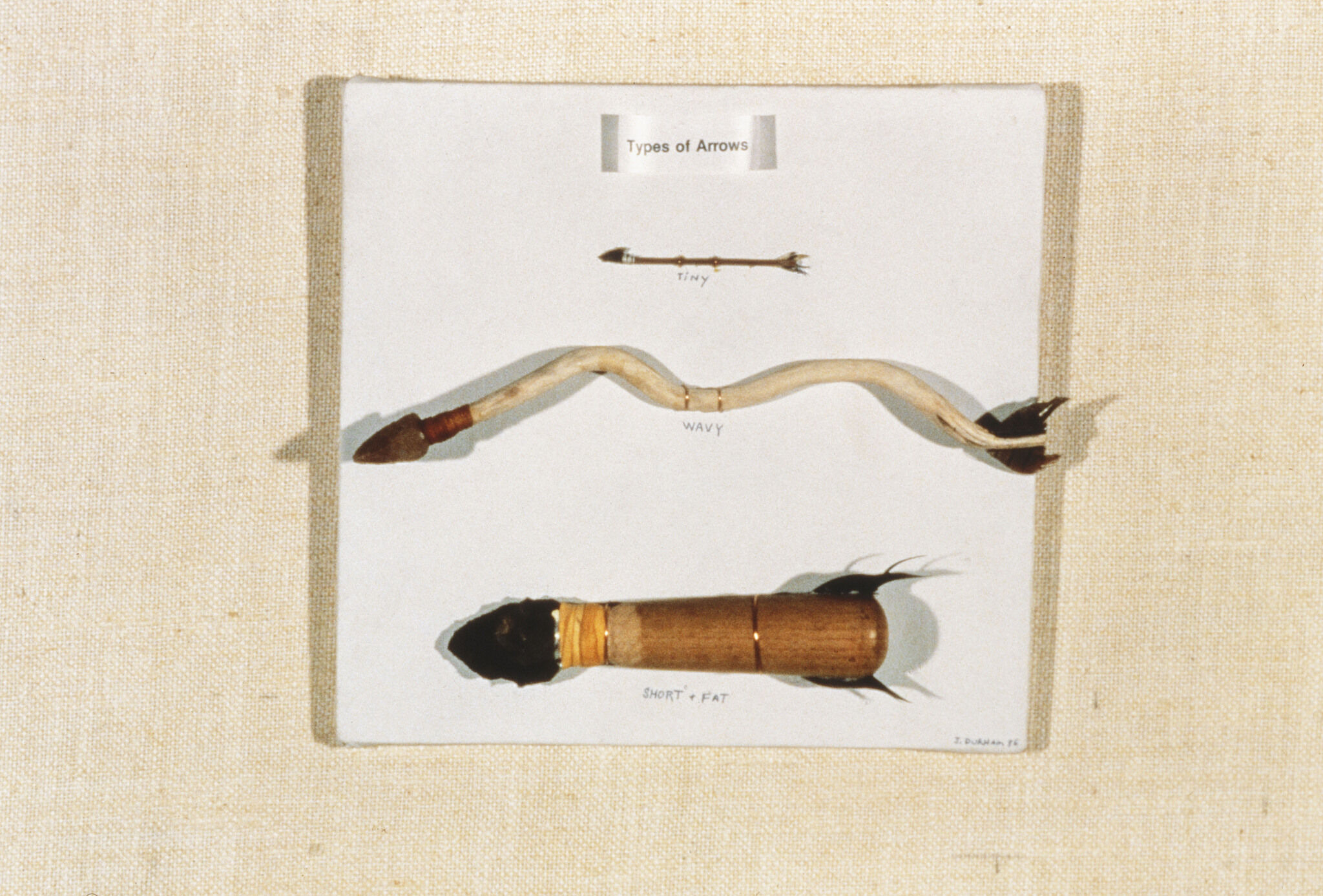

Jimmie Durham

Types of Arrows, 1985-86

In thousands of cowboy and Indian films, a cowboy takes an arrow out of another cowboy and looks at it and said, "It's not Apache. It's Cheyenne." or "It's not Navajo. It's Apache." I'm charmed by the ideas that everybody has signature arrows [laughs] that you can tell, maybe you can even tell the name of the mother and the guy who made the arrow. It's so specific!

I thought I will make some things and I will show some things that could just as well be something, or not. I made a little wavy arrow and a tiny, tiny arrow. They all have real arrow points on them. They all have real flint points. I just wanted to make something ridiculous to show how ridiculous it already is. And do it in way that doesn’t accuse anybody of being racist, because it doesn’t help to accuse people of being racist; it just makes them angry. But if you say, "Here are three types of arrows," then so ridiculous, then people laugh. Suddenly, they're removed from it for a little while and can see it, maybe can see it.

"I don't want them to laugh at the genocide, but I want them to laugh at three ridiculous arrows." —Jimmie Durham

Artist as Critic:

Humor, Irony, Satire

"I've always loved comedy as a way of fighting, and comedy as a way of disrupting. I like it very much. The transition from politics to art and art to politics never stops, and it is a constant in my life." ―Jimmie Durham

Whitney audio guide stop for On Loan from the Museum of the American Indian

a. Have students look closely at On Loan from the Museum of the American Indian, 1985 and Types of Arrows. What do they notice? Where would they expect to find displays like this?

“I was struck by the idea, Museum of THE American Indian. It’s such a clumsy term. You wouldn’t say, Museum of the Italian. Museum of the Jew. Museum of the Black. It’s not nice to do that, is it? Then I said, that’s something to poke at. That’s something to play with.” —Jimmie Durham

b. Give your students some information about the items in the case that Durham referred to as “fake artifacts.” Ask students to divide into small groups and discuss the objects that Durham has displayed in this work. Use the resources below. How might they relate to stereotypes about Native Americans? Ask each group to report back to the class. What did they discover?

Six Misconceptions about Native American People - Youtube

Article by Farah Qureshi about Native American mascot and Media Stereotypes

Hollywood stereotyped Native Americans - Youtube

Matika Wilbur, Changing the Way We See Native Americans, TEDxTeachersCollege.

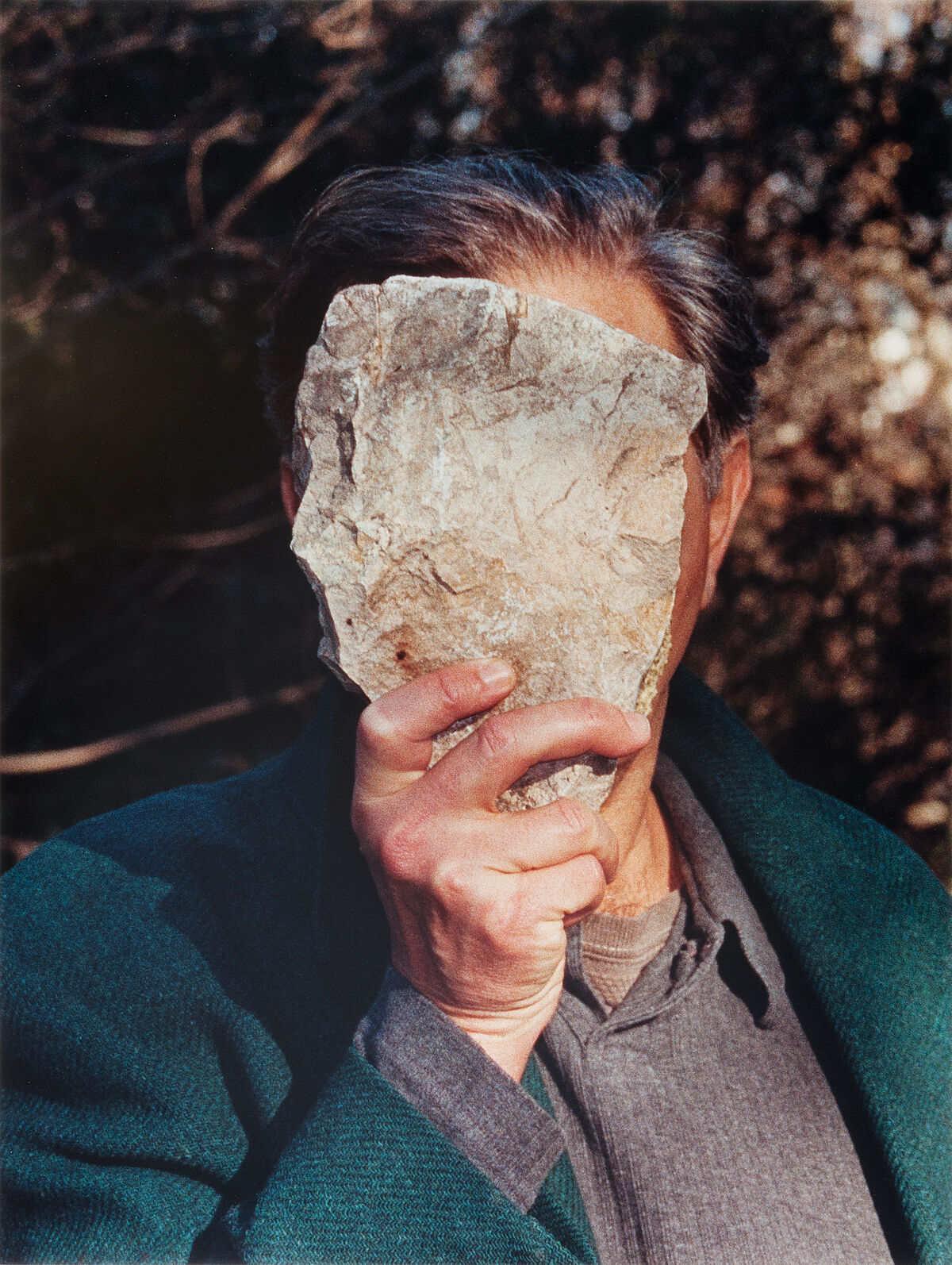

Jimmie Durham

Self Portrait Pretending to be a Stone Statue of Myself, 2006

Durham uses self-portraiture to explore the idea that identity is not singular or autonomous, but rather an amalgamation of the many influences that shape us over time. Here he holds a piece of stone over his face like a mask.

“But of course, I'm not pretending to be. I'm pretending to be pretending to be. This idea comes from an old Japanese idea that I love very much. The Middle Ages Japanese court had a special language that you pretended to be pretending to be sorrowful if a friend died. You pretended to be pretending to be happy if something happy happened.

I just like the idea of a double pretense, that you're not really living your life. You're not really there at all. I don't know how ‘here’ I am, but I know the self-portrait is already a double pretense.” –Jimmie Durham

Whitney audio guide stop for Self Portrait Pretending to be a Stone Statue of Myself

Artist as Experimenter:

Portraits and Pretense

a. With your students look at Durham’s Self-Portrait Pretending to Be a Stone Statue of Myself and discuss why an artist might create a self-portrait. What do students expect a self-portrait to include? Have your students ever made self portraits? What did they include? Why?

b. Ask your students to view Durham’s self-portrait and describe what the artist is doing. Tell students the title of the portrait. Ask them to turn and talk about why the artist might have made that choice. Why do students think he is covering his face? What might Durham mean by “pretending to be a stone statue of myself…” What do students think he is choosing to tell about himself? What is he not telling?

Post-visit Activities

Post-visit Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artists’ ideas through discussion, art-making, and writing activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask your students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Jimmie Durham

ST. FRIGO, 1996

St. Frigo is a sculpture Durham made in 1996 while doing an artist residency in France. By throwing stones at an old refrigerator every morning for ten days in the courtyard of Le Collège Gallery in Reims, Durham physically transformed the appliance from what he described as a “neutral” everyday object into a valuable and unique sculpture, saving it from the rubbish bin. Durham also made an experimental video of this ritual titled Stoning the Refrigerator. Later commenting that the refrigerator had been “brave,” Durham decided to call the sculpture St. Frigo, as if it were a martyred saint.

Artist as Experimenter:

Altered Objects

a. Have students reflect on Durham’s sculpture St. Frigo, 1996 and discuss how this work was made. Explain that Durham threw stones at this fridge for ten days and discuss what Durham thought about the experience of this object and how he transformed a mundane household item into a work of art, saving it from the trash. He also felt bad about the fridge, remarking that it had been brave, like a martyred saint, and so he called the refrigerator St. Frigo.

b. Ask students to debate why this fridge might be considered art. Have them think about what Durham did, what his ideas and process were, and what the viewers’ responses might be. Divide the class in half, with one group advocating for the refrigerator as art, and the other group challenging this idea.

c. Students could work in small groups for this project. Ask student groups to find an object or a material, such as an old map or chair, that your school is throwing out. Have students alter that object a little bit every day over the course of two weeks. As a group, ask them to decide what their process will be for transforming this object. For example, making a small tear in a paper object or using a pencil to make a few marks on a chair each day. View and discuss students’ finished work. What titles would students give their transformed objects?

Artist as Critic:

Critical Ideas

a. Review and discuss the images of Durham’s artworks in this teacher guide. What do students think Durham is being critical of? Why? Having visited the exhibition, how can they tell?

b. Ask student volunteers to lead a discussion with the class about some of the stereotypes that they may have experienced concerning their identities—gender, race, name, personality, or where they are from. Ask each student to write a brief paragraph about how people stereotype them, based on their identity.

c. Ask your students to write a second paragraph to explain who they feel they really are. What are their personal goals, tastes, style? What gives each student their own special identity?

d. Have students write a summary or conclusion about what advice they can give to people about the dangers of stereotyping and how to change people’s attitudes.

e. If students were going to design a humorous or satirical exhibition about their own experiences of being stereotyped, what would they choose to include? Why? How might students use materials, objects, and humor to address and confront these stereotypes?

f. Divide students into small groups and have them design an exhibition display that challenges stereotypes. Each person in the group could make a small artwork that incorporates humor and satire to include in their show. Student groups can find images of objects and materials for their artworks online or in magazines. Each group could create a collaborative drawing, a collage, a model, or a digital rendering of their exhibition.

View and discuss students’ artwork and exhibition designs with the class. What did they create? How did they incorporate humor and satire in their artworks? How did they choose to display their work?

Bibliography and links

/exhibitions/jimmie-durham

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World exhibition on whitney.org.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/02/arts/design/jimmie-durham-review-whitney-museum-cherokee.html

The New York Times review of Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World at the Whitney.

https://hammer.ucla.edu/exhibitions/2017/jimmie-durham-at-the-center-of-the-world/

Hammer Museum information about Jimmie Durham, biography, and images.

https://walkerart.org/calendar/2017/jimmie-durham-center-world

Walker Art Center information about the exhibition Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World.

http://www.vulture.com/2017/11/jimmie-durham-at-the-center-of-the-world-whitney-museum.html

New York Magazine article about Jimmie Durham’s identity.

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2015/11/25/457256340/despite-similarities-pocahontas-gets-love-malinche-gets-hate-why

National Public Radio information about Malinche and Cortés.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GHdW_LVfn28

"Six misconceptions about Native American people."

https://journalistsresource.org/studies/society/race-society/native-americans-media-stereotype-redskins

Article by Farah Qureshi about Native American mascot and media stereotypes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_hJFi7SRH7Q

"How Hollywood stereotyped Native Americans."

https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/whats-problem-thinking-indian-women-princesses-or-squaws

Bitch Media article about Native America women stereotypes.

/collection/works

The Whitney’s collection.

/education

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

/for-teachers

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Isabelle Dow, Assistant to School and Educator Programs, Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs, and Kristin Roeder, Whitney Educator.

Education Programs are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, the Dalio Foundation, The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation, Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Barker Welfare Foundation, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and the Whitney's Education Committee.

Endowment support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, The Paul & Karen Levy Family Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Steven Tisch, Lise and Michael Evans, Barry and Mimi Sternlicht, Laurie M. Tisch, and Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools are endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World is organized by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

The exhibition is made possible, in part, by generous support from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Henry Luce Foundation.

In New York, generous endowment support is provided by The Keith Haring Foundation Exhibition Fund.