Teacher Guide:

Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection

Apr 27, 2016

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection. Drawn entirely from the Museum’s holdings, the more than two hundred works in the exhibition explore changing approaches to portraiture from the early 1900s until today.

Bringing iconic works together with lesser-known examples and recent acquisitions in a range of mediums, the exhibition unfolds in eleven thematic sections on the sixth and seventh floors. Through their varied takes on the portrait, the artists represented in Human Interest raise provocative questions about who we are and how we perceive and commemorate others.

This teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We anticipate a high demand for our Guided Visits of this exhibition, which are free for New York City public schools. Please visit /education/schools-educators/k-12 to sign up.

Guided Visits are now offered in Spanish! Sign up now!

¡Ahora se ofrecen visitas guiadas en español! ¡Inscríbete ahora!

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team at the Whitney

Human Interest: Portratis from the Whitney's Collection

Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection offers new perspectives on one of art’s oldest genres. Some of the thematic groupings in the exhibition concentrate on focused periods of time, while others span the twentieth and twenty-first centuries to forge links between the past and the present. This sense of connection is one of portraiture’s most important aims, whether memorializing famous individuals long gone or calling to mind loved ones near at hand.

Portraits are one of the richest veins of the Whitney’s collection, a result of the Museum’s longstanding commitment to the figurative tradition, which was championed by its founder, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. The works included in this exhibition propose diverse and often unconventional ways of representing an individual. Many artists reconsider the pursuit of external likeness—portraiture’s usual objective—within formal or conceptual explorations or reject it altogether. Some revel in the genre’s glamorous allure, while others critique its elitist associations and instead call attention to the banal or even the grotesque.

Once a rarefied luxury good, portraits are now ubiquitous. Readily reproducible and ever-more accessible, photography has played a particularly vital role in the democratization of portraiture. Most recently, the proliferation of smartphones and the rise of social media have unleashed an unprecedented stream of portraits in the form of snapshots and selfies. Many contemporary artists confront this situation, stressing the fluidity of identity in a world where technology and the mass media are omnipresent.

Human Interest is curated by Scott Rothkopf, Deputy Director for Programs and Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator, and Dana Miller, Richard DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Permanent Collection, with Mia Curran, curatorial assistant; Jennie Goldstein, assistant curator; and Sasha Nicholas, consulting curator.

Sources

Exhibition wall text, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2016.

More about the exhibition

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. We have included selected images from the exhibition, along with relevant information that you may want to use before or after your Museum visit. You can print out the images or project them in your classroom.

Pre-visit Objectives:

- Introduce students to portraits and their diverse representations in twentieth century and contemporary American art.

- Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how artists have interpreted the genre of portraiture.

Artist as observer

What is a portrait?

A portrait is a description or representation of a person, but portraiture can take on many different forms and possibilities. For example, a portrait can be an accurate depiction of physical appearance, a resemblance of a subject, a conceptual or symbolic representation, or an imaginary, idealized portrayal. We are surrounded by portraits every day—from the bills and coins in our wallets to selfies, social media, and photographs on people’s mobile devices. Historically, portraiture was an important symbol of power and luxury. Now readily reproducible and ever-more accessible, photography has played a particularly vital role in the democratization of portraiture. Today, portraiture is a way for artists to define themselves in relation to contemporary life.

a. Ask your students to discuss what a portrait might be. When students think of the word portrait, what comes to mind? What does it mean to portray someone? Have students consider portraits in different mediums, such as art, literature, poetry, film, and theater. Talk about portraits in their everyday lives.

b. Create a word cloud of students’ definitions. What might a portrait share or reveal about a person? What can students learn about the person or people in a portrait?

Artist as storyteller

Self-portraits

Self-portraiture is the genre that gives the artist the greatest freedom from external constraints. The artist is his or her most available model. In making a self-portrait, the creator becomes both the subject and the object. Self-portraiture can be a tool for introspection and self-exploration, or it may simply be a record of physical appearance at a particular time and place. A self-portrait can be literal or imaginary, an exercise in self-awareness, or a creative imaginary persona in an elaborate setting.

a. Ask your students to define and discuss the differences between portraits and self-portraits.

View and discuss the self-portraits by Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Edward Hopper with your students. Have them describe what they see in each image and compare them.

What has the artist included in each self-portrait?

What is real and what isn’t?

What is hinted at?

Do students think the artists intentionally left anything out? Why?

What questions are students left with?

b. Consider how each artist has represented him or herself through pose, gesture, facial expression, gaze, background details, and clothing.

What can students infer or know about the artist, based on what is portrayed in each image?

To what extent do these portraits seem to focus on physical or external likeness?

To what extent do these portraits share features beyond likeness?

c. If your students constructed self-portraits in words, how would they describe themselves? Ask students to refer to their word cloud for inspiration and consider how they might describe themselves. Ask them to make a list of the things about themselves that people can see.

d. How do others describe them? Ask students to make a list of the things about themselves that are invisible to the eye. Discuss how visual artists might reveal those invisible things, for example, using a background, objects, or accessories.

Artist as Experimenter

Portraits of the people

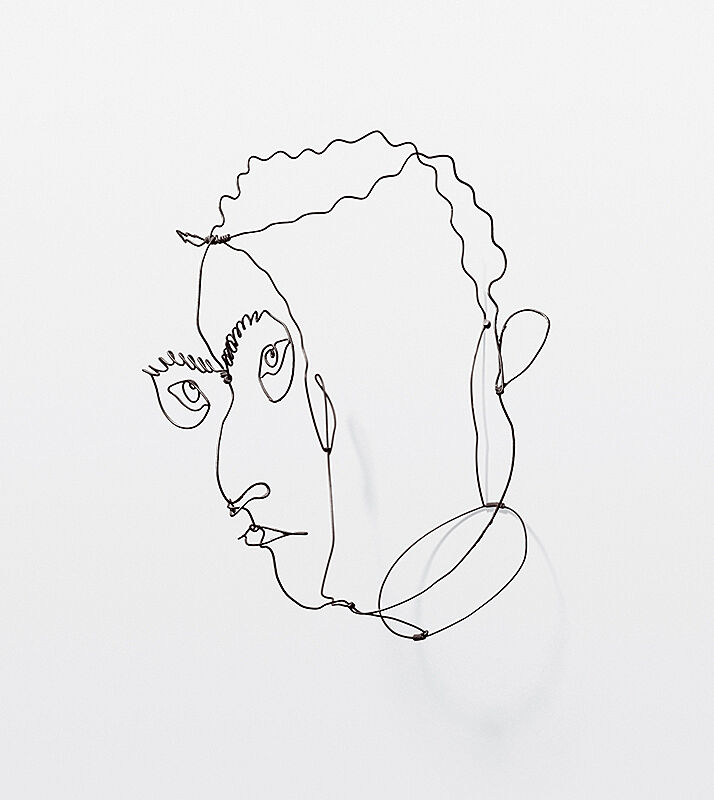

The image of this work by Alexander calder may look like a two-dimensional drawing in reproduction, but it is made of wire, like a three-dimensional contour drawing in space. The word “contour” means outline in French. A contour drawing is a drawing that depicts a subject or object only in lines. A blind contour drawing is a drawing exercise in which an artist makes a line drawing of a subject without looking down at the paper.

a. Have your students find a partner and decide who will pose and who will draw. Let the sitter choose a facial expression based on what their mood is at that particular moment. Have the other partner make a blind contour drawing of the sitter’s head—draw by keeping their pencil on the paper and their eyes on the sitter. Don’t look down at the paper until the drawing is complete.

b. Display and discuss students’ drawings. Which of their classmates can students recognize? How do they recognize their classmates? Is it because of details? Expressions? Mood? Anything else?

Artist as Experimenter

PORTRAITS WITHOUT PEOPLE

Marsden Hartley’s Painting Number 5, 1914-15 is a portrait of his close friend, Karl von Freyburg. Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting, Summer Days, 1936 can be seen as a type of self-portrait. The symbols of the flowers, animal skull, and the New Mexican environment where O’Keeffe lived for many years suggests things about her such as place, likes, and personal interests.

a. With your students, compare and discuss Painting, Number 5 by Marsden Hartley and Summer Days by Georgia O’Keeffe. What do students notice about each of these portraits without people?

b. Ask your students to create a symbolic portrait of themselves or someone they know. What signs or symbols would students include? Have students use shapes, colors, designs, and symbols which represent the person without drawing a picture of what they look like.

c. Think about what is important to this person. Ask students to take notes. Which occupation, special interest, or hobby does this person have? What are their initials? What special items of clothing do they wear? What is their favorite color? Where do they spend time?

d. View and discuss the finished portraits with the class. What can students tell about the person by looking at each other’s symbolic portraits?

Post-visit Activities

Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and topics from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artists’ ideas through discussion and artmaking activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? How did the exhibition change their ideas about what a painting can be? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Artist as Observer

REALITY CHECK

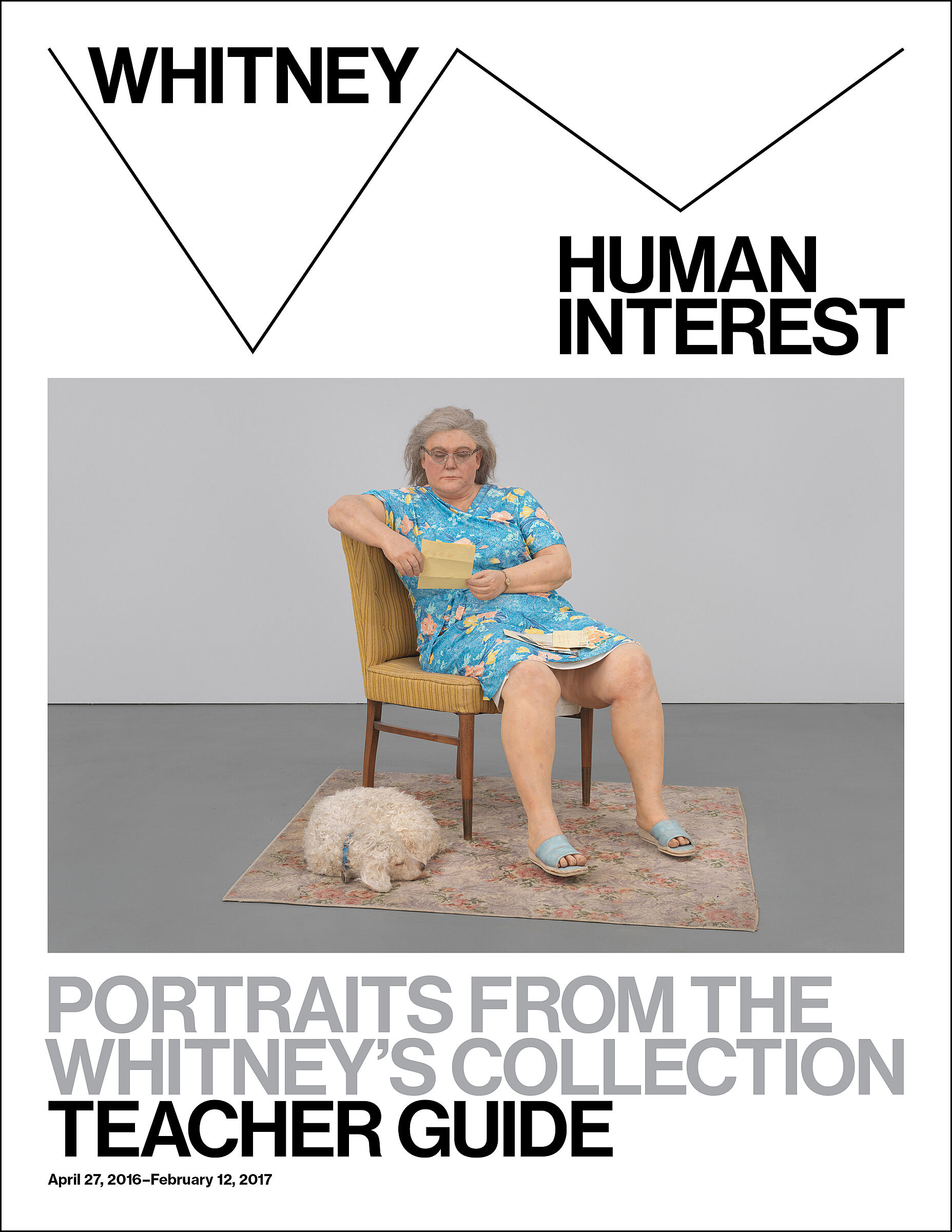

Review and discuss Duane Hanson’s Woman and Dog if your students saw it at the Museum.

What was students’ initial response to Duane Hanson’s work? Why?

What did students think about when looking at his figures?

Have students think of a person in their family or close friend. What everyday moment would they choose to focus on to represent that person?

Why this particular moment?

What setting would they be in?

How would they pose?

What would they wear?

What accessories would they include?

How about pets?

What everyday moment might capture something important about that person’s identity?

As a journal activity, ask students to describe that everyday moment and setting, and what it might reveal about that person’s identity.

If students were to choose a significant moment in their own lives to depict, what would they focus on and why?

Artist as Observer

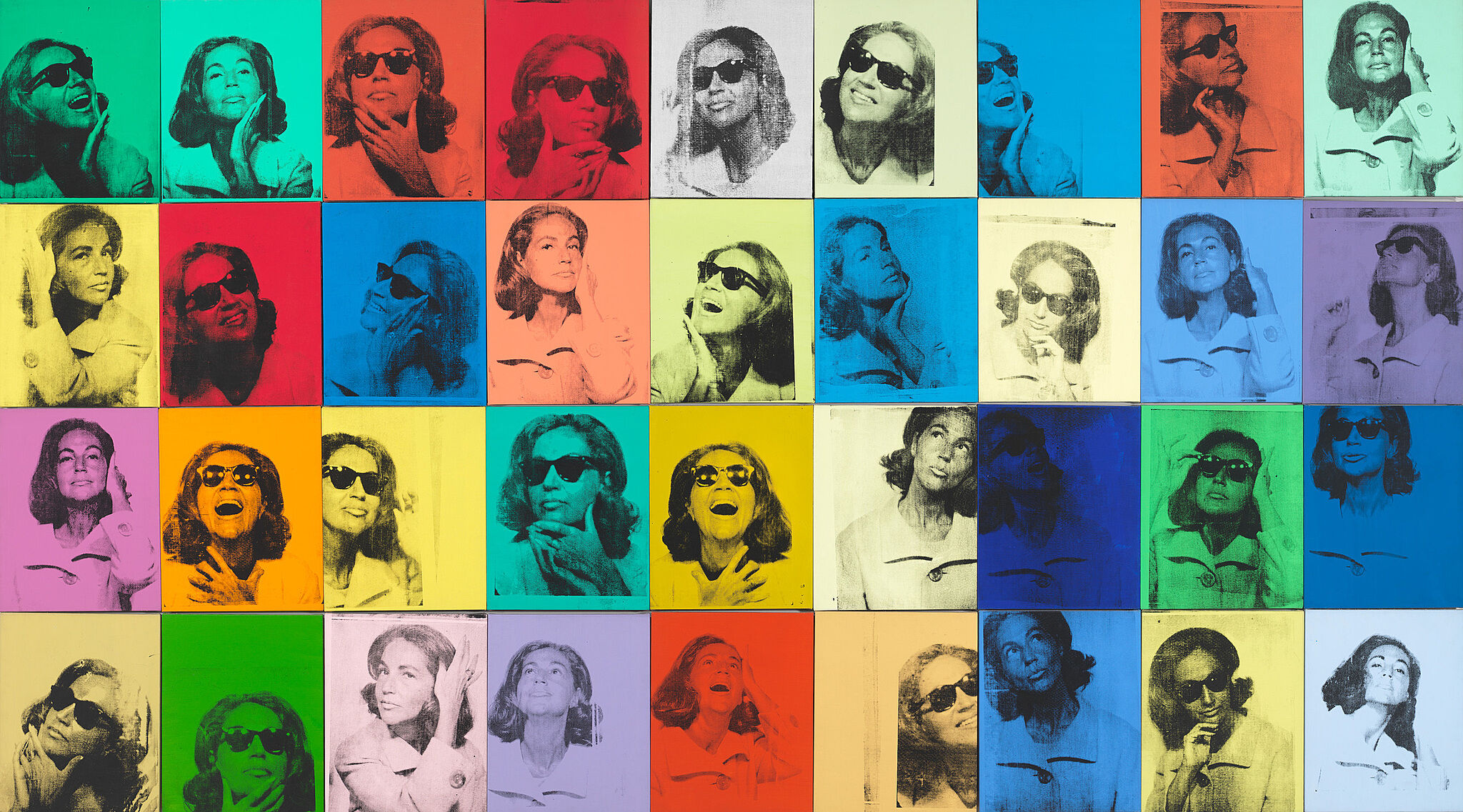

MULTIPLE SELF-PORTRAIT

a. Ask students to find a partner and decide who will be the photographer and who will be the sitter. Ask the photographers to take pictures of the sitters using six different gestures and facial expressions as directed by the photographers. Have partners switch roles.

b. Ask students to download their images to a computer, print them out, and then exchange images with another pair. Ask student partners to study the images and come up with a list of adjectives that describe the persona communicated by the six images.

c. View and discuss students’ photo sets and descriptions with the class. What roles or personae did the subjects take on? Did their expressions successfully communicate the intended personae to the other students in the class? Why or why not?

d. For younger students, have the class brainstorm a nuanced emotion that can be captured in a photograph and ask the class to enact it at the same time. Take one group photograph or separate photos of each student that you can then print and display in a grid format.

e. View and discuss the pictures of your students. What similarities and differences do they notice?

ARTIST AS CRITIC

SYNECDOCHE AND METONYMY

In their work, Byron Kim and Gary Simmons represent people without showing their whole physical presence, but they do it in different ways. Synecdoche is a figure of speech in which a part stands for the whole or vice versa. For example, in Synecdoche [Whitney Artists], 1999-2001, Kim represents artists in the Whitney’s collection by their skin color. Metonymy is a figure of speech in which something is called by a name that is associated with it in meaning, but not its own name.For example the phrase “let me give you a hand” is a metonymy for “let me help you.” In Lineup, Gary Simmons uses visual metonymy by representing young men in a police lineup with eight empty pairs of sneakers.

a.Ask your students to discuss and compare these works by Gary Simmons and Byron Kim.

How are they both parts that stand for the whole?

How do they expose and critique racism and stereotypes?

b. Ask students to think about the ways in which they have been been stereotyped. What did they do to address or challenge this stereotyping? Ask students to discuss their stereotypes with the class or write a journal entry about it.

c. Ask students to use synecdoche or metonymy to represent themselves in a self-portrait. Consider which part of themselves would challenge the stereotype and create a meaningful representation of themselves.

What media or materials would they use? Why?

What would they want to communicate about who they are? On the outside? On the inside?

What objects or images would they include?

How could they represent something about themselves that people can’t see?

d. View and discuss students’ self-portraits. What does the synecdoche or metonymy communicate about their identities?

Images and Related Information

Edward Hopper

SELF-PORTRAIT, 1925-30

Although Edward Hopper drew and painted numerous self-portraits in his early years as an artist, this is one of the few he completed later in his career. Around 1918, Hopper made an etching in which he portrayed himself wearing a hat. In Self-Portrait, he preserves the pose of this earlier image, while his mature and thoughtful appearance suggests the effects of time’s passage. Dressed in suit and tie, Hopper gives no indication of his profession; indeed, he appears as the antithesis of the stereotypical bohemian artist. Though the interior space Hopper occupies is nondescript, his hat suggests a moment of transition—that he is on his way somewhere else. Like so many of the people he portrayed on trains, and in hotels and waiting rooms, Hopper is captured in a contemplative moment, engaged in a scene that hints at narrative possibilities but remains mysterious.

NJIDEKA AKUNYILI CROSBY

PORTALS, 2016

Njideka Akunyili Crosby (b. 1983; Enugu, Nigeria) is a Los-Angeles based artist who makes large-scale, representational work that combines collage, drawing, painting, and printmaking. She routinely fuses both Nigerian and American influences and source material, reflecting on contemporary African life as well as her experience as an expatriate living in the United States and the inherent difficulty of navigating these two realms. Portals is composed of an invented interior. The left panel features a prominent self-portrait. On the right-hand side, the work portrays framed pictures of multiple generations of her family—the artist’s parents, her in-laws, her grandmother, and her own wedding. Commemorative portrait fabric—a customized material often made for special events in Nigeria, in this case the artist’s mother’s senate campaign—functions as part of the architectural backdrop of the diptych. The areas of the composition that extend from the walls onto the floor include transfer images of album covers featuring Nigerian musicians among other items. Like much of her work, Portals considers Akunyili Crosby’s life and the cultural complexities of the dual worlds that she inhabits.

ALEXANDER calder

VARÈSE, C. 1930

In Paris during the late 1920s, Alexander calder arrived at his revolutionary notion of “drawing in space,” a concept that remained central to his work throughout his sculptural career. calder’s wire portrait heads were made from 1928 to about 1932, and they serve as a visual record of those he knew. At once linear and volumetric, these works act as three dimensional, continuous line drawings. Avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse (1885-1965) and the artist lived in the same building in Paris. In this portrait, suspended from the ceiling in the exhibition, calder captured the essence of Varèse’s personality and features—even though the sculpture is made of nothing but steel wire.

MARSDEN HARTLEY

PAINTING, NUMBER 5, 1914-15

Marsden Hartley began this work before the First World War during an extended stay in Berlin, where he was captivated by the city’s vitality and imperial Germany’s military pageantry. The painting is a memorial to Karl von Freyburg, a young German military officer whom Hartley loved and who was killed in battle soon after the war began. Combining the fragmented forms of Cubism with German Expressionism’s brilliant colors, Hartley broke apart and rearranged motifs derived from German flags and such military regalia as epaulets, brass buttons, and an Iron Cross medal (awarded for bravery), as well as a chessboard recalling von Freyburg’s favorite game. The result is both an exuberant portrait and a mournful reminder of the human cost of war.

Georgia O’Keeffe

SUMMER DAYS, 1936

In Summer Days, Georgia O’Keeffe suspended an animal skull and several Southwestern flowers above a barren desert landscape. The large scale of the bones and blossoms and their placement in the sky give the painting a surreal quality. For O’Keeffe, the animal skull and vibrant flowers were symbols of the cycles of life and death that shape the natural world. This composition belongs to a group of paintings in which the artist depicted the sun-bleached bones she brought back east from her summer sojourns in New Mexico. The deer, horse, mule, and steer skulls she collected became potent souvenirs of a landscape that had deeply inspired her. As she explained, “The bones cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive in the desert.”

DUANE HANSON

WOMAN WITH DOG, 1977

Like most of Duane Hanson’s sculptures, Woman with Dog projects an uncanny appearance of reality. Hanson often worked on a single figure for up to one year—locating models, making polyvinyl casts directly from their bodies (a method he developed in 1967). assembling and accurately hand-painting skin, veins, and blemishes, and finally outfitting the sculptures with real clothing and accessories. In addition to the figure, a heightened sense of reality is emphasized by the dog, which is made of ceramic but its coat is comprised of real dog hair clippings from his cousin’s poodle. Despite their extreme realism, however, Hanson’s sculptures are not usually likenesses of specific people. The pile of letters in this sculpture, for example, is addressed to a Minnie Johnson, but the model for the work was someone else who lived near Hanson’s Florida studio. Woman with Dog thus presents a constructed, even composite character.

Georgia O’Keeffe

ETHEL SCULL 36 TIMES, 1963

Hired to produce one of his first commissioned portraits, Andy Warhol escorted art collector Ethel Scull to a Photomat in a Times Square pinball arcade. Under the artist’s guidance, she posed with and without her large sunglasses, appearing alternately glamorous and playful, serious and vacuous. This grid of thirty-six silkscreened panels reproduces about twenty-three of the more than one hundred resulting photographs. A pose can occasionally be seen twice, differentiated by color, orientation, or its position on the panel. With its insistent, cinematic multiplicity of expressions and poses, Warhol’s portrait elevates Ethel to the iconic realm previously reserved for his depictions of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe.

BYRON KIM

SYNECDOCHE [WHITNEY ARTISTS], 1999-2001

Begun in 1991 and comprising 400 panels, Synecdoche is an ongoing project in which Byron Kim records the unique skin tones of friends and fellow artists on monochrome painted panels. The panels that belong to the Whitney represent the skin colors of forty artists with work in the Whitney’s collection, including Kim himself. The polychromatic grid references the formal language of abstract painting, yet Kim rejects the notion of pure abstraction or “art for art’s sake.” Although each panel serves as a sort of portrait of an artist, it pointedly refuses to tell us anything about the subject. The title of the work is a figure of speech in which part of a thing is made to stand for the whole. This work questions how that idea applies to individual identity—specifically, the notion that skin color might represent the whole of an individual.

GARY SIMMONS

LINEUP, 1993

In Lineup, Gary Simmons uses the absence of the human body to challenge stereotypes about the black male as criminal suspect. Simmons’s installation mimics the appearance of a police lineup wall in the early 1990s, complete with notations to mark the height of the suspects and a raised platform on which they will stand for presentation to witnesses. Instead of lining up the “suspects” of a real crime, however, Lineup displays eight empty pairs of sneakers, ranging from Puma Clydes to Air Jordans. The sneakers function in a variety of ways: they stand for stereotypes of young black men, but underscore their physical absence from the scene and, perhaps their innocence of the crime. Lineup also refers to the troubling police practice of “rounding up” young men of color to serve as phony or filler “suspects” in criminal lineups. By using sneakers rather than human figures for identification, Simmons implies that the police view young black men as no more distinguishable than one pair of sneakers from the other.

Bibliography and links

Miller, Dana, Ed. Whitney Museum of American Art: Handbook of the Collection. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015.

Brilliant, Richard. Portraiture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Freeland, Cynthia. Portraits and Persons. OUP Oxford, 2010.

Pointon, Marcia. Portrayal: and the Search for Identity. Reaktion Books, 2012.

Rohmer, Harriet, Ed. Just Like Me, Stories and Portraits by Fourteen Artists. Children’s Book Press, 2013.

The Whitney’s collection.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; and Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation; The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation; Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody; Joanne Leonhardt Cassullo and The Dorothea L. Leonhardt Foundation, Inc.; the Barker Welfare Foundation; Con Edison; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Generous endowment support for education programs is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch, Steve Tisch, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, and Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection is sponsored by

Major support is provided by Anne Cox Chambers and Helen and Charles Schwab.

Generous support is provided by The Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston.