Teacher Guide:

2017 Biennial

Mar 17, 2017

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the Whitney Biennial 2017 exhibition, on view at the Museum through June 11, 2017. This is the first Biennial to be held in the Whitney’s home in the Meatpacking District.

Established in 1932, the Biennial often generates critical discussions about contemporary art, while providing an opportunity for deep thinking and reflection on the broader cultural concerns of a given historical moment. Bringing together mostly new or recent work by both emerging and established artists, the Whitney Biennial 2017 exhibition continues this tradition.

This teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and provides suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team at the Whitney

Whitney Biennial 2017

The Whitney Biennial 2017 is the seventy-eighth iteration of the longest running survey of contemporary American art. The exhibition features painting, sculpture, drawing, installation, film, video, photography, activism, performance, music, and video-game design by sixty-three individuals and collectives.

This Biennial arrives at a time rife with racial tensions, economic inequities, and polarizing politics, and many works in the exhibition challenge us to consider how these realities affect our senses of self and community. Throughout the exhibition, artists test the limits of timeworn structures and protocols, claim space for direct experience and personal agency, and create alternate zones or worlds. Some spotlight particular social issues, such as financial debt, violence, or access to equal opportunities, while others model imaginative ways of relating to history and place, or represent the importance of reverence for the land. Still others embolden the pleasures of slow contemplation or formal abstraction, inviting us to pause and pose questions in a tumultuous world.

Curated by the Whitney’s Nancy and Fred Poses Associate Curator Christopher Y. Lew and independent curator Mia Locks, the Whitney Biennial 2017 spans the lower level, first, third, fifth, and sixth floors, and the outdoor galleries. The Biennial film program presents weekend screenings in the theater on the third floor. The film program is organized by Christopher Y. Lew, Mia Locks, and Aily Nash.

Find the film program schedule and more information about the exhibition here: /exhibitions/2017-biennial

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. We have included selected images from the exhibition, along with relevant information that you may want to use before or after your Museum visit. You can print out the images or project them in your classroom.

Objectives:

- Invite students to think about expanded definitions of art.

- Help students explore and make sense of recent events.

- Introduce students to topics and themes they may encounter in the exhibition.

- Introduce students to selected works by Biennial 2017 artists.

Artist as Experimenter

Is it Art?

The Biennial 2017 exhibition features the work of contemporary artists who explore different ways of experiencing and interpreting the world around them. Some artists experiment with materials and approaches, other artists draw our attention to important social and political issues, others ask us to pause and reflect, and many challenge our ideas about what art can be.

a. What makes something a work of art? What characteristics does a work of art have? Who decides? Ask your students to spend time thinking and writing about their personal definitions of art. Share and discuss students’ writing and ask them to save it for further discussion after their Biennial visit.

Artist as Storyteller

Post-it

Many of the artists in the Biennial 2017 exhibition refer to recent tumultuous events, such as mass migration, climate change, police violence, and political turmoil. Some artists focus on specific events and the transformations that have occurred as a result, while others address broader themes.

a. Ask your students to think of a recent event that they consider important. The event can be national, global, local, or personal. Have students research and use post-its to take notes about these events. Use different color post-its for different types of events (eg green for global, blue for national, red for local, yellow for personal).

b. Discuss the events that students selected. Why are they important? What social, political, or cultural impact did these events have nationally? Globally? Locally? On their own lives? How did these events transform them on a personal level? In their community?

c. Have students create a post-it wall of their events. Ask them first to arrange the post-its into global, national, local, and personal categories. Next, have them look for connections between events and the stories they tell. Do global, national, local, or personal events overlap? How? Ask students to rearrange the post-its to reflect the connections they find. When you visit the Museum, have your students look for connections between the events they discussed and the art on view in the exhibition.

Artist as Experimenter

Frame This

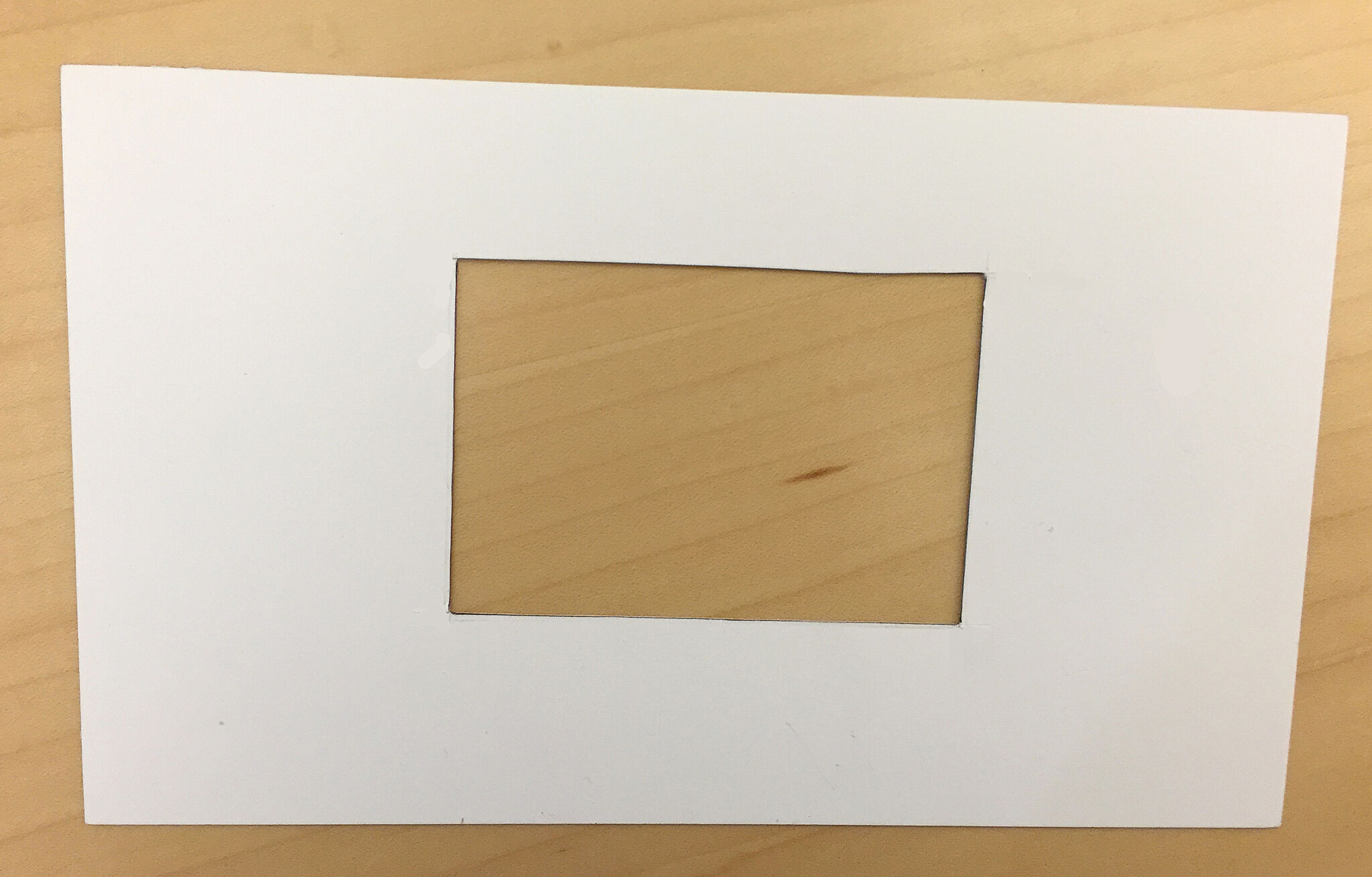

In her paintings, Shara Hughes includes various framing devices to give the viewer a sense that s/he is looking at the image from a specific vantage point. Framing describes the boundary around an image and the way that the image is cropped, calling attention to what is and is not included in the image. Framing reveals the artist’s decisions about how an image is constructed and the meaning the artist wants to convey.

a. A viewfinder is a useful device for framing a composition. It allows you to crop and frame a scene within a specific area. You can look through a viewfinder and move it around to find the most engaging composition. Ask your students to create a viewfinder out of card stock to use as a framing device. Students can make a viewfinder by cutting or tearing paper. A traditional viewfinder has a rectangular opening, but encourage your students to experiment with creating an interesting shape for their viewfinders. Fold the card in half. Draw a shape in the center of the card and cut or tear out the shape. Leave a border all the way around the edges of the card. Older students could use an object they find in the classroom as a viewfinder. For example, the handle of a pair of scissors or the view through the opening of a stapler.

b. Ask students to frame a scene in their classroom with their viewfinder and draw what they see through it. Have them use the shape of their viewfinder as a “frame” for their drawing. Have students make three changes to the scene so that it becomes more surprising. Have them use crayons, colored pencils, or markers to add color to their scene.

c. View and discuss students’ drawings. How does the framing change their experience of looking? What changes did they make to the scene so that it became more surprising?

d. Older students could discuss composition and why an artist might use an actual frame on a painting.

Artist as Storyteller

Know Your Neighbor

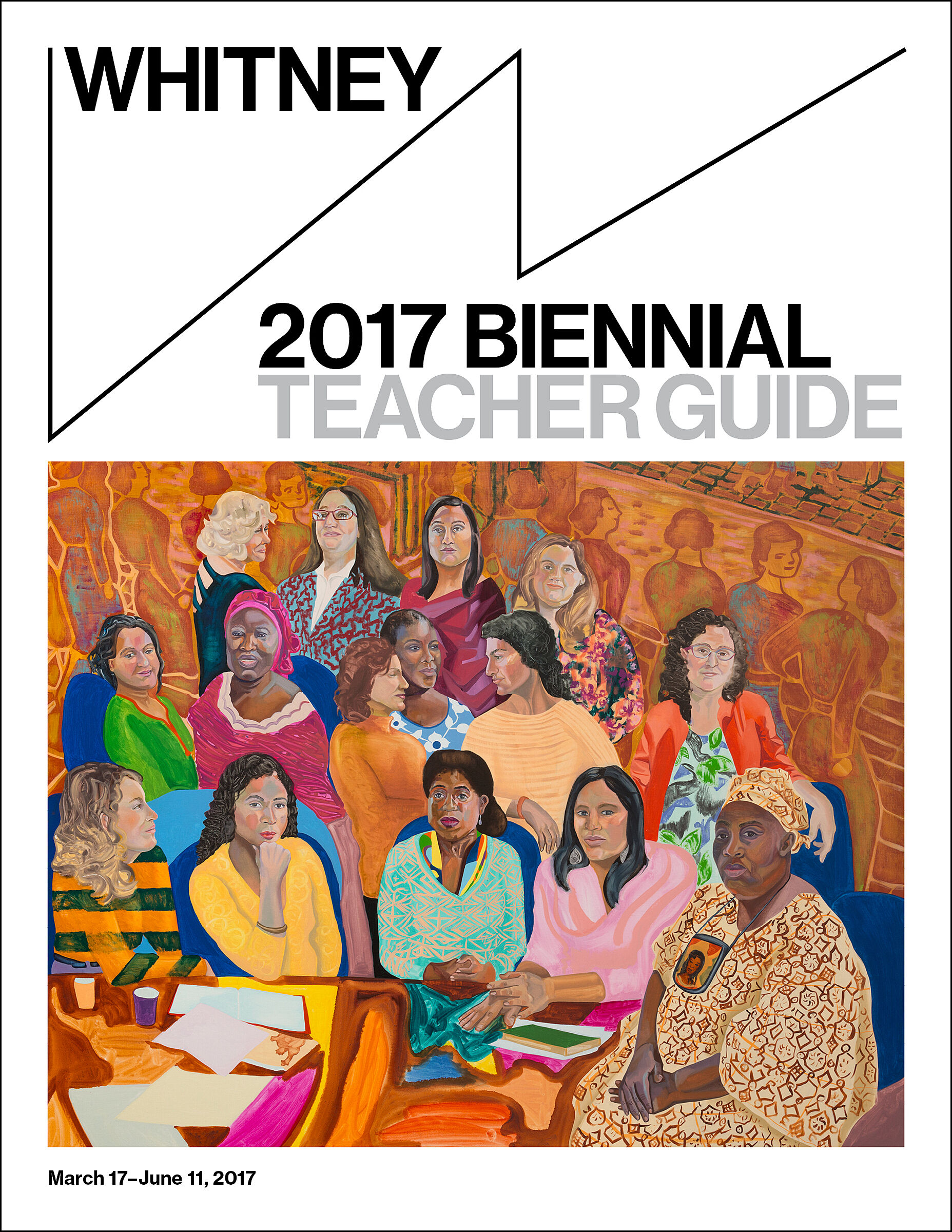

a. View and discuss Aliza Nisenbaum’s painting with your students. Ask them to describe what they see in this work—especially the details of the figures’ surroundings. Can they identify any of the objects in the painting?

b. Ask students to find a partner and interview each other using the following questions based on Nisenbaum’s painting. Have them make notes about their partner’s answers.

How do you spend your Sunday morning?

Where do you like to hang out?

Who do you enjoy hanging out with?

What is your favorite thing to wear?

What do you like to read?

Ask students to come up with additional questions for their interview.

c. Ask students to draw a portrait of their partner and include information from their interview.

d. Display and discuss students’ portraits. In what ways are their portraits similar? How are they different? Ask students to identify something new that they learned about their classmates by looking at their portraits.

Artist as Observer

Seeing the Everyday Anew

a. Oto Gillen deftly exploits photography’s capacity to crop, focus, and reassemble in order to render the ordinary unfamiliar and new. As an assignment, ask students to use the camera on a smartphone to take a photograph outdoors. The picture could be taken either during the day or at night. It could be taken on their way to or from school. Ask them to focus on a detail close up or an unusual view of their surroundings. Have them think about cropping, framing, zooming in, and composition.

b. Ask students to email the photographs so that you can collect and print them out.

c. Have students divide into small groups. Ask each group to arrange or “curate” their images in a sequence on a table or classroom wall. Oto Gillen sequenced his images from day to night. How will they sequence theirs? Ask students to consider content, color, location, time of day, or another type of sequence. Think about the shape of their image arrangement. Will the images be placed in a line, a random cluster, a square, a circle, or another configuration?

d. Ask students to discuss the arrangement and sequence of their photographs. What choices did they make? What view of their surroundings did students create collectively? Why did they choose to sequence their images in that order? In sequencing their photographs, did students see their surroundings in a different way? How?

Artist as Critic

Signs, Plaques, Markers

a. Ask your class to discuss where you have signage in your school. Is this signage helpful? Is it valued? Is any signage missing that would highlight things that are important to students? Where? What signs would students make to address things that go unnoticed?

b. Ask students to think of something in their neighborhood that is important to them, but maybe not valued by everyone in their community. Ask them to create signs for this site. What did they come up with? Why did they choose that place?

c. The road signs that McArthur produced are the ones that communicate historical and cultural information. Ask your students to imagine that sometime in the future, an historical or cultural plaque will be installed on their classroom seat in their honor, recognizing their accomplishments and contributions to society.

d. Have each student imagine themselves in the future. What is their greatest accomplishment? What would their plaque commemorate? For example, are they a famous musician, artist, or athelete? The first woman to land on Mars? Have they cured a disease? Discovered a new element on the periodic table? Ask students to invent their own future history and create an historical or cultural plaque for themselves. Have them clearly indicate the historical or cultural significance it is meant to highlight. Have students look in their neighborhood for cultural medallions. New York City teachers can use the resource below.

http://www.hlpcculturalmedallions.org/browse-cultural-medallions/borough.php

Listing of cultural medallions on buildings in New York City boroughs.

Post-visit Activities

Objectives:

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss selected ideas and themes from the 2017 Biennial exhibition and revisit their definitions of art.

- Have students further explore some of the artists’ approaches through discussion and art-making activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

We recommend that you do this activity the day after your Museum visit. Ask students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? What other questions do they have? Did the exhibition challenge or expand students’ definition of art? Did the work on view connect to any of the events that students chose for pre-visit activity 2 (Post-It)? How? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Artist as Critic

Climate Change

a. Discuss how Jon Kessler uses objects and technology to draw attention to the ways in which global warming and climate change affect people and the planet.

b. Ask your students to draw a human who has evolved to cope with climate change. Have students consider how they could alter parts of the person’s body. What devices and tools will they need to survive? What will their surroundings look like? Encourage your students to fill the whole sheet of paper.

c. Students could bring in found objects and materials to create a three-dimensional work based on their drawings. You could give your students the choice of working on their own or collaborating in small groups or pairs.

Artist As Experiment

Museum as Classroom, Classroom as Museum

a. Discuss students’ experience of seeing Chemi Rosado-Seijo’s Salón-Sala-Salón. What were their reactions and responses? Ask students to think of one new thing they learned about their peers, their teacher, or themselves.

b. Discuss the characteristics of classrooms and museums with your students. What are the special features of a classroom? A museum? What makes these places function? How are they safe? Interesting? Provocative? What features of classrooms and museums would students like to change? Why would they change these features?

c. Ask students to work in small groups to design their ideal classroom. Have them consider how their classroom is arranged and how the arrangement affects the ways in which they use the space. Have each group create a list or plan of what they would need in their ideal classroom. Have them take notes about what the items would be used for. Students could also construct a model of their ideal classroom using cardboard, paper, or recycled materials.

d. Ask student groups to present and discuss their proposals and models with the class. What changes did they make to their learning environment? Which special features did students include in their ideal classrooms?

Artist as Critic

A Very Long Line

a. Review and discuss A Very Long Line with your students. View a short video here: http://postcommodity.com/AVeryLongLine.html

What associations do students have with the phrase “a very long line?” Discuss the presence and purpose of borders and why they exist. Who enforces them?

b. Have students use the following resources to read about and discuss the Mexican border.

http://www.warscapes.com/retrospectives/uncertain-borders/excerpts-borderlandsla-frontera

Excerpts from Borderlands/ La Frontera: The New Mestiza, (1987, 2012) and by Gloria Anzaldúa.

Why do they think the artists decided to focus on this border? Talk about why the artists might have chosen to surround the viewer with visual representations of the US Mexico border and titled their work A Very Long Line. What multiple meanings might the title convey?

c. Ask students to divide into small groups. Have each group use the resources below to research historical and contemporary walls around the world and report back to the class. Each group can research why the wall was built, what they are made of, and whether (or not) the wall was pulled down.

http://origins.osu.edu/connecting-history/top-ten-origins-walls

https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/a-brief-history-of-border-walls

http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/7-famous-border-walls

http://www.wonderslist.com/10-most-famous-walls-in-the-world/

Artist as Storyteller

A Narrative Dimension

a. Connect this activity to your literature studies and curriculum. With your students, discuss the experience of seeing Samara Golden’s work. Watch a video about her work.

b. Think about Golden’s installation as the setting for a story, play, or movie. Ask students what story they imagine unfolding in this environment.

c. With your students, generate a list of storytelling genres, for example: mystery, romance, horror, science fiction, etc. Ask students to divide into small groups. Ask each student group to choose a genre and write a collaborative story. The story should include some third person narrative and some dialogue. Be sure to develop the characters in the story. Each story should have a conflict and a resolution. Include at least three concrete objects or details that students remember about the installation. Present and discuss students’ stories. Are there similarities and differences?

Images and Related Information

Shara Hughes

In the Clear, 2016

The lush medleys of color, pattern, and texture within Shara Hughes’s landscape paintings are products of both her imagination and her painterly process. Referencing painting’s traditional role of offering a window onto another world, Hughes’s work often presents framed views of hallucinatory realms. Hughes frequently begins a composition by altering the canvas surface in ways that she then has to improvise against. She might cover part of the canvas in a gesso¾a thick, gluelike substance that lends the surface a solid feeling—or she might spray paint the canvas from behind, making marks that emerge murkily from beneath the weave. These opening moves serve as the artist’s challenge to herself, concrete realities that she must respond to in her creation of psychological scenes that are part landscape, part abstraction.

Aliza Nisenbaum

La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016

Aliza Nisenbaum’s portraits make use of bold color and pattern in order to frame modest, intimate scenes. She often depicts undocumented immigrants, many of whom Nisenbaum first met while she was teaching a class called “English through Art History.” Nisenbaum works with live models and thinks of the encounter between artist and sitter as an ethical one in which the two parties come to trust and know each other well. Her images personalize the immigrant experience and give visibility to the normally invisible.

Oto Gillen

New York, 2015–Ongoing

Oto Gillen’s New York is at once familiar and strange, mundane and futuristic, as if glimpsed, in the artist’s words, “through a door slightly ajar.” A New Yorker since birth, he spent more than a year walking the city’s streets to create this work. The gradual rise of a tower at the World Trade Center complex and the seasonal changes of New York’s ubiquitous honey locust trees mark the passage of time in his ever-shifting portrait of the city. Views of passersby and close-ups of objects record the intimate, fleeting encounters of daily life at street level, while images of looming skyscrapers convey the city’s vast scale and evolving skyline. Gillen’s photographs capture individual residents but also allude to the larger economic, political, and social forces that entangle them.

Park McArthur

Another Word For Memory is Life, 2017

Park McArthur produced this work following federal specifications for signs designating cultural points of interest such as museums, national parks, and battlefields. As directed by the Manual of Unified Traffic Control Devices, she had the signs manufactured in .125 aluminum with rounded radius edges, using Pantone color Brown 469. McArthur’s signs differ from those produced by the government, however, in that they are blank.

The Whitney Museum itself is an almost textbook example of the kind of cultural site that official roadside signs would typically designate. But in their openness, McArthur’s works also maintain the possibly of gesturing toward points of interest that fall outside of traditional histories, including those that have been radically transformed by—even lost to—the gentrifying city, such as the Meatpacking District, or the West Side piers that were once sites of a thriving shipping industry and centers of gay art, sex, and life.

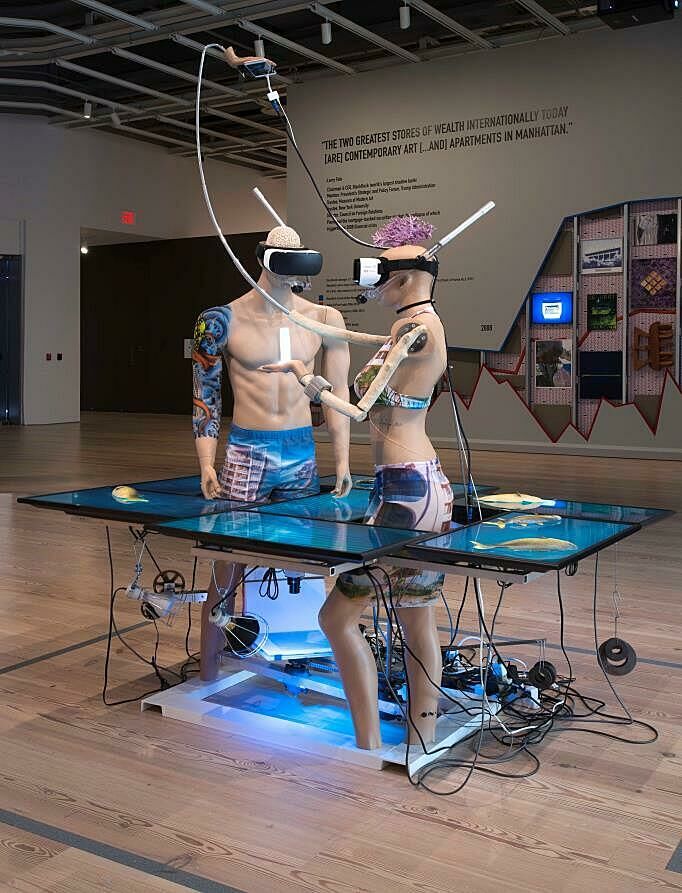

Jon Kessler

Evolution, 2016

Jon Kessler makes what he calls “performative sculptures,” whose humor and kitsch belie their serious critique. The two works on view, Exodus and Evolution, are part of a larger in-process project, The Floating World, which addresses the social and environmental impacts of climate change. In Exodus, the series of eBay-sourced figurines that rotate around a screen in an endless march are evocative of mass migrations of people, whether from natural disasters or political situations such as the Syrian refugee crisis. Evolution focuses attention on rising sea levels; two figures in snorkel gear take pictures, apparently indifferent to or ignorant of any impending danger. The repeating image of a proposed luxury residential skyscraper by the late architect Zaha Hadid reinforces the artist’s point: even as the effects of climate change displace millions in low-lying areas, those who can afford not to care are still choosing to build waterfront pleasure palaces.

Chemi Rosado-Seijo

Salón-Sala-Salón (Classroom/Gallery/Classroom), 2017

Chemi Rosado-Seijo’s contribution to the Biennial is a conceptual project with everyday implications. A gallery from the exhibition has been “moved” to the Lower Manhattan Arts Academy, a public high school on the Lower East Side, while a classroom from the school has been moved to the Whitney. Students from the school meet in the Museum for their lessons over the course of the exhibition, and works by Biennial artists Sky Hopinka and Jessi Reaves are on view in the school.

Like many of Rosado-Seijo’s projects, Salón-Sala-Salón (Classroom/Gallery/Classroom) has an exploratory nature, in this case resulting from different social groups coming together for a period of time. The energy of the large group of young, curious students activates the Museum to function differently, while placing artworks at the school recontextualizes them as tools for learning.

Postcommodity

A Very Long Line, 2016

Postcommodity is an artist collective whose current members are Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez, and Kade L. Twist. Their video installation, A Very Long Line, focuses on the border between the United States and Mexico, an emotionally and politically charged site that has become even more contentious through the 2016 election and the beginning of the current presidential administration.

The installation is designed to disorient, with spinning video projections and out-of-sync audio evoking “genesis amnesia,” or the condition of forgetting one’s own origins. In this case, what has been forgotten—primarily by citizens of the United States—is the Indigenous status of peoples from the Western Hemisphere, including immigrants from Mexico and Guatemala. Forgotten, too, are the Indigenous trade and migration routes that have crisscrossed what is now the border since before European colonization. Filmed from the window of a car, A Very Long Line brings those routes into the dizzying present, one in which the border is never fully known or understood.

Samara Golden

The Meat Grinder's Iron Clothes, 2017

Samara Golden addresses the idea of psychological space through disassembled interior architecture, often creating illusions with reflective surfaces and upended objects and rooms. Here, her site-specific installation adjoins the Museum’s formidable west-facing windows. Golden’s work incorporates these windows as well as the river and sky beyond, with mirrors placed on the ceiling and floor creating an infinite visual abyss. The structure is stratified, both spatially and socially. Using handmade sculptures of furniture and other everyday objects, she creates a series of environments seemingly in conflict with each other: a penthouse apartment, an image of aspirational wealth; a middle-class home full of art projects and plants; a drab, cluttered office; and an institutional space that the artist describes as part hospital, part prison. Viewed from an elevated platform, the installation has a disorienting effect, evoking the anxiety produced by a political climate rife with social and economic inequality.

Bibliography and Links

Whitney Biennial 2017. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press and Whitney Museum of American Art, 2017.

http://sharahughesart.blogspot.com/

Shara Hughes’s blog with examples of her paintings.

http://alizanisenbaum.com/artist-statment.html

Aliza Nisenbaum.

A selection of New York photographs by Oto Gillen.

http://bombmagazine.org/article/1000039/park-mcarthur

Bomb Magazine interview with Park McArthur.

http://postcommodity.com/About.html

Postcommodity.

http://www.chemirosado-seijo.com/

Chemi Rosado-Seijo.

http://samaragolden.com/home.html

Samara Golden.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Mark Joshua Epstein, Whitney Educator;Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs; and Jamie Rosenfeld, Coordinator of School and Educator Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, the Dalio Foundation, The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation, Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Barker Welfare Foundation, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in

partnership with the City Council, by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee, and contributions from family and friends made in memory of Jill Buttenwieser Schloss.

Endowment support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick, Laurie M. Tisch, and Steve Tisch.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools are endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

Whitney Biennial 2017 is presented by

Major support is provided by

Major support is also provided by The Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston and the National Committee of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Significant support is provided by the Philip and Janice Levin Foundation.

Generous support is provided by 2017 Biennial Committee Co-Chairs: Leslie Bluhm, Beth Rudin DeWoody, Bob Gersh, and Miyoung Lee; 2017 Biennial Committee members: Ashley Leeds and Christopher Harland, Diane and Adam E. Max, Teresa Tsai, Suzanne and Bob Cochran, Rebecca and Martin Eisenberg, Amanda and Glenn Fuhrman, Barbara and Michael Gamson, Kourosh Larizadeh and Luis Pardo, and Jackson Tang; the Henry Peterson Foundation; and anonymous donors.

Additional support provided by the Austrian Federal Chancellery and Phileas – A Fund for Contemporary Art.

Funding is also provided by special Biennial endowments created by Melva Bucksbaum, Emily Fisher Landau, Leonard A. Lauder, and Fern and Lenard Tessler.

Additional endowment support is provided by The Keith Haring Foundation Exhibition Fund, Donna Perret Rosen and Benjamin M. Rosen, and the Jon and Mary Shirley Foundation.

Curatorial research and travel for this exhibition were funded by an endowment established by Rosina Lee Yue and Bert A. Lies, Jr., MD.

New York magazine is the exclusive media sponsor of Whitney Biennial 2017.