Teacher Guide:

Whitney Biennial 2014

Mar 7, 2014

About the Guide

1. How can these materials be used?

These materials provide a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

2. Which grade levels are these materials intended for?

These lessons and activities have been written for Elementary, Middle, or High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs.

3. Learning standards

The projects and activities in these curriculum materials address national and state learning standards for the arts, English language arts, social studies, and technology.

4. Feedback

Please let us know what you think of these materials. How did you use them? What worked or didn’t work? Email us at schoolprograms@whitney.org.

About the exhibition

What is contemporary art in the United States now? The Whitney Biennial asks this question every two years—and each time finds that the answer has changed. The Biennial exhibition is often described as a “survey” of contemporary American art. This has never really been true, for the answer to the Biennial’s central question is always up for debate: the art of our own time, by its very nature, is constantly evolving.

For the 2014 Biennial, the last one before the Museum moves to its new downtown location, the Whitney has taken the unusual step of inviting three curators from outside the Museum—Stuart Comer, Anthony Elms, and Michelle Grabner—to select works for one of the Museum’s three main floors. Together, these curators literally broaden the Whitney’s horizons, for none of them were based in New York when exhibition planning began: Elms lives in Philadelphia, Grabner in Chicago and rural Wisconsin, and Comer was in London but has since moved to New York. Elms and Grabner are both artists as well as established curators while Comer has largely worked with film, video, and performance. The three share a reluctance to define, summarize, or systematize current artistic practices. Working together has allowed each curator to dig deeply into his or her own unique interests and areas of expertise, to be committed and partial, and to trust that the whole would round out the parts.

The exhibition has 103 participants—many of them collectives or partnerships with two or more members. Painting features here more prominently than in recent Biennials, but so does work that may be surprising to find in an exhibition at an art museum. There is a strong literary presence, as novelists, poets, publishers, and editorial collectives appear throughout the show. Many works are hybrids, mixing multiple media and ideas in order to reflect critically on notions of everything from art, architecture, and technology to history, identity, and global politics. A number of artists included in the exhibition have themselves chosen to work as curators—in some cases selecting objects that speak to each other critically or poetically, in other instances calling attention to or re-creating the work of artists who have passed away but provide an illuminating precedent for present-day concerns. It is a heterogenous group, including both younger and older figures, all producing work that is vital and relevant to the present moment.

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the 2014 Biennial exhibition. You may want to introduce students to at least one work of art that they will see at the Museum. See the Images and Related Information section for examples of artists and works that may have particular relevance to the classroom.

Objectives:

Introduce students to selected works by 2014 Biennial artists.

Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit such as “Artist as Observer” and "Artist as Experimenter.”

Consider new materials and processes.

Think about expanded definitions of art.

ARTIST AS CRITIC

IS IT ART?

The 2014 Biennial exhibition features the work of artists who explore different ways of experiencing and interpreting the world around them. Some artists experiment with unusual materials and playful approaches, other artists draw our attention to important social and political issues, while others ask us to pause and reflect. These artists often challenge our ideas about what art can be.

What makes something a work of art? What characteristics does a work of art have? Who decides? Ask your students to spend time thinking and writing about their personal deifnitiions of art. Share and discuss students’ writing and ask them to save it for a further discussion after their Biennial visit.

Artist as Experimenter

CUT AND PASTE

Susan Howe creates poetry out of found text from literary or history books and documents. She culls excerpts from the texts as well as the marginal text such as footnotes and table of contents. Using copies of these sources, she cuts out sentences and fragments, pasting and taping them together but retaining the typefaces, spacing, and rhythms of the original source. Her compositions are built both by control and chance arrangements. Howe said: “. . .I often think of the space of a page as a stage, with words, letters, syllable characters moving across.”

a. Use these resources to view and discuss the ways in which Susan Howe creates poetry:

Susan Howe on the Poetry Foundation’s website.

Susan Howe, The Art of Poetry No. 97, interviewed by Maureen N. McLane, Paris Review.

b. Ask students to use found text to create a poem with a shape. Have students think of something that inspires them, such as a book, movie, music, sports, politics, or current events. You could also relate this project to the literature, music, and art that students are studying in class, or use the Whitney’s website to create a found poem in response to a work of art: /collection/works or /exhibitions/2014-biennial

c. Ask students to find text from magazines, newspapers, subway maps, school flyers and newspapers, menus, computer printouts, text on the Internet, and scrap paper. As they choose the text, have students pay attention to font, form, size, scale, and color. Ask them to experiment with the composition of the text and how it will look on the paper—with control and by chance.

d. What shape do students want their poem to take? How does the poem’s shape relate to its content? Use magic tape or glue sticks or clear tape to adhere the found text to a sheet of paper. Have students share their poems with the class. What shapes and subjects did students choose? What surprised students about their poems?

Artist as Experimenter

FOLLOW THE THREAD

Sheila Hicks designed her site-specific textile work, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column (2014) with the architecture of the Museum building in mind, considering the coffered, open design of the ceiling and the sense of solidity she found in the stone floor. By extending the cords from the ceiling to the floor, she hopes to activate viewers’ awareness of these architectural elements. She said: “I want my work to hit the floor in a very emphatic way so it hits the floor, spills, puddles, and looks as though it’s alive. It’s moving and has its own internal energy.”

a. Ask students to find a partner and experiment with a piece of thread about 12-18” long. Drop the thread onto a horizontal surface (eg the floor or a table top). Have students draw the shape of the thread and then repeat the process once or twice.

b. Ask students to do the drawings on vellum or other translucent paper such as tracing paper. Have student partners layer their drawings and staple them at the top. Ask students to share their drawings with the class. How did the thread respond to movement? Gravity? The surface students dropped it on?

c. As a follow up assignment at home, have students do same activity but with items that have personal significance to them—for example, a belt, lanyard, necklace, ribbon or twine from a gift, or rainbow loom elastic chains. Have students take photographs or make drawings of the results. What was the personal significance of the fibers that students chose? In what ways did these items respond to movement and gravity?

Post-visit Activities

Objectives

Enable students to reflect upon and discuss selected ideas and themes from the 2014 Biennial exhibition and their definitions of art.

Have students further explore some of the artists’ approaches through discussion and art-making activities.

Make connections with artists’ sources of inspiration.

Artist as Experimenter

LOST IN TRANSLATION

Ken Okiishi often creates works that explore the moments when language and images begin to fall apart and there are breakdowns in communication. His paintings on video screens focus on these moments of indeterminacy, changing our experience of what both video and painting can be.

a. Where do students notice language, image, and communication breakdown in their everyday lives? For example, words on signage may make the sign mean something different than originally intended, glitches when a mobile phone has poor service, garbled subway announcments, pixellation on TV screens, or the selfie function on digital phones as a mirror reflection rather than your actual self. How do our brains fill in the blanks?

b. Ask students to find and print two copies of an image that interests them. Have them use acrylic paint on acetate to make monoprints over the printouts of the images. Or ask students to print out a digital image that interests them. Use a paint program on the computer to make a digital painting. Put the original image back in the printer and print the digital painting over it.

c. Ask students to look at each others’ images. How has the information shifted, changed, or broken down? In what ways has its meaning changed?

Artist as Observer

BRING THE OUTSIDE INSIDE

For the 2014 Biennial exhibition, Zoe Leonard turned part of the fourth-floor gallery into a giant camera obscura. By inviting us into the camera obscura, Leonard asks us to slow down, to look with close attention, and to listen to the ambient sound in the space.

a. Turn your classroom into a camera obscura! You’ll need a roll of black photographic paper, duct tape, a lens from a camera or flashlight, and a pushpin.

b. Use a white, blank classroom wall opposite a window with a view, or cover the wall with a large piece of white paper. Cover all of the windows in your classroom with black photographic paper so that no light is coming through. In the center fothe window, make a hole in the black paper that is the size and shape of the lens. Tape the lens over the hole. The only light entering the room should be through the lens.

c. After a few minutes, your eyes will adjust to the dark, and an image should appear on the wall opposite the window. The image will be upside down and in reverse, like a mirror image. Ask students to spend time looking closely at the image. What do they see in the camera obscura image that they don’t usually focus on when they look out the window? What do they notice about the sounds outside?

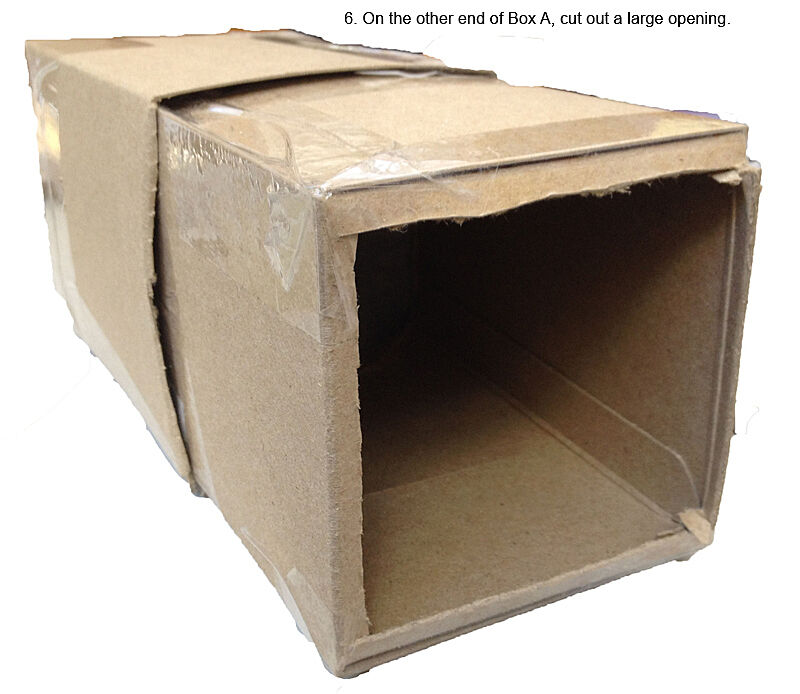

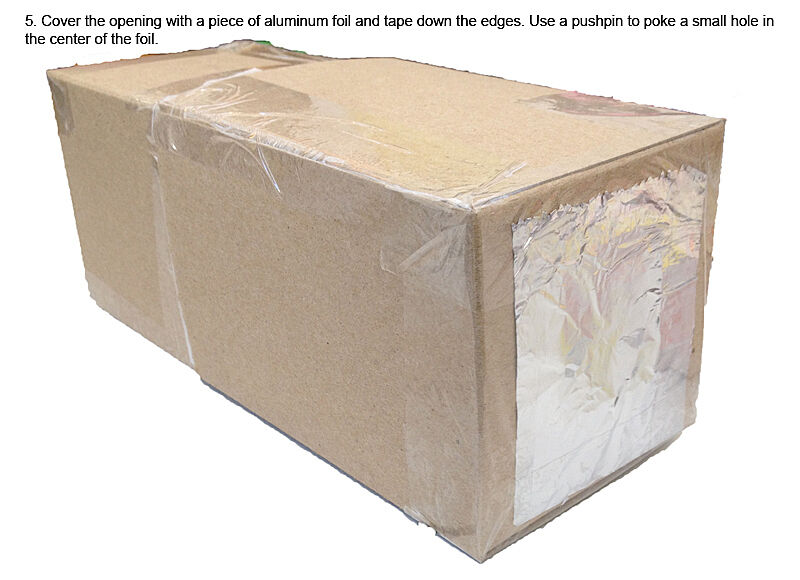

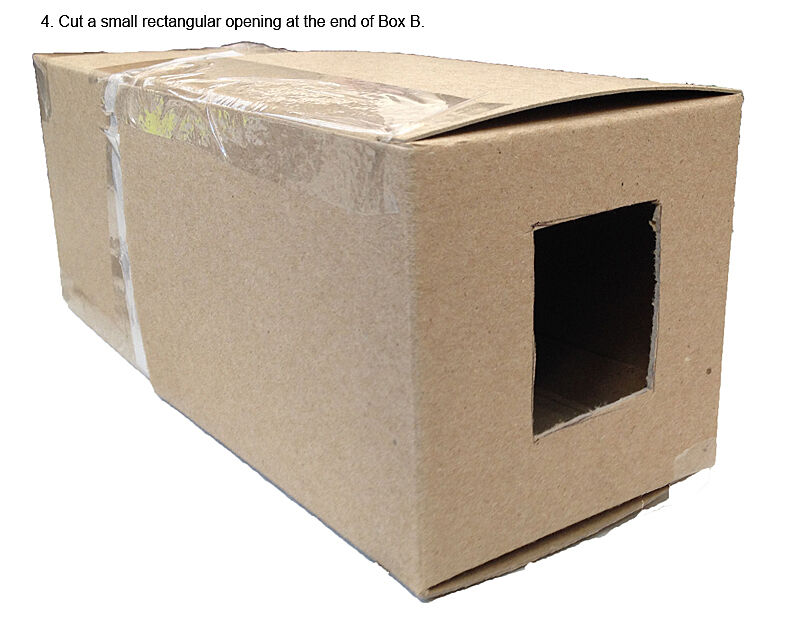

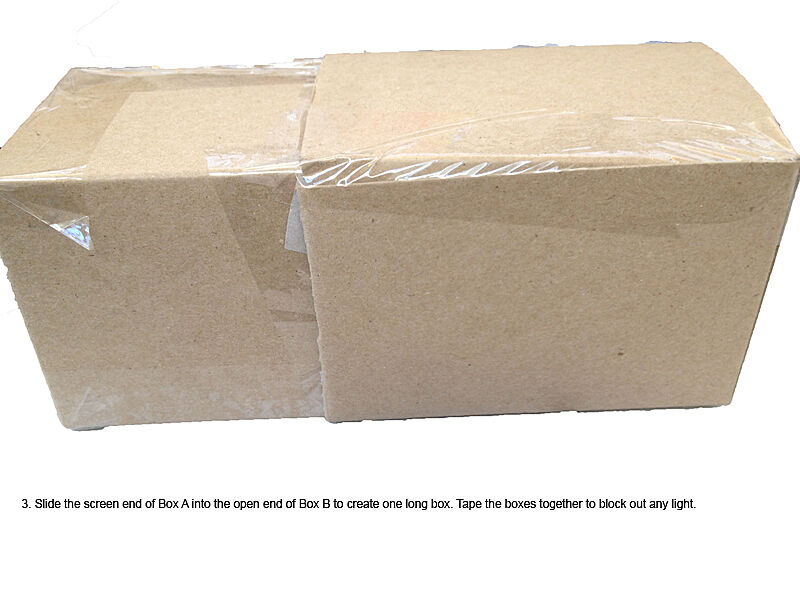

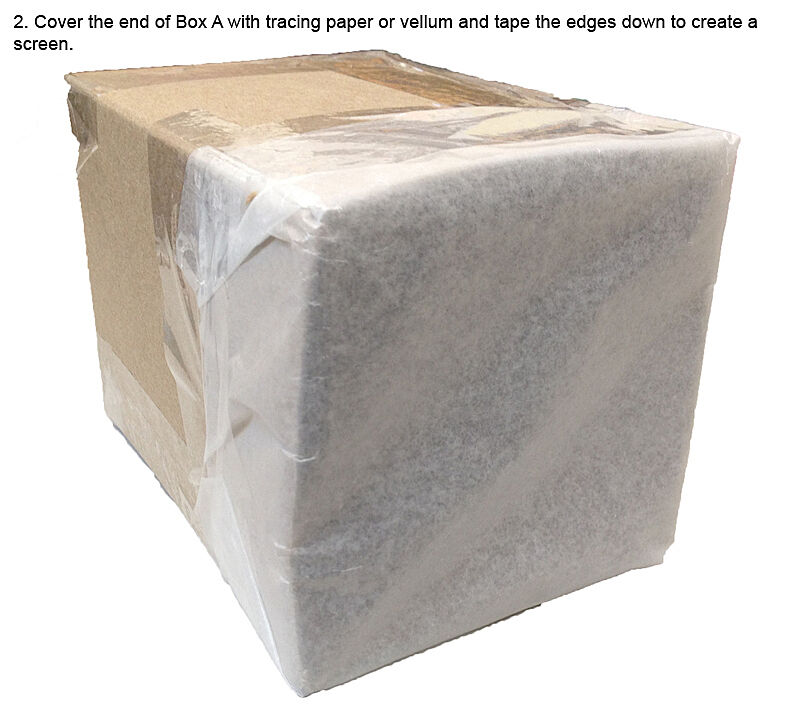

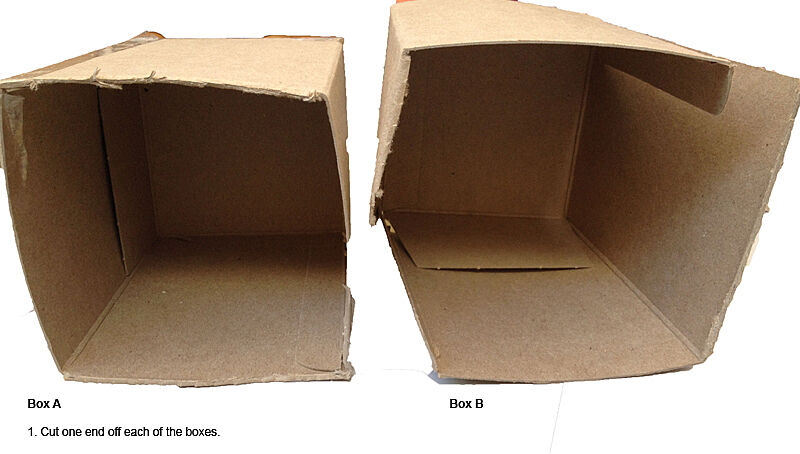

d. You may want to make smaller camera obscuras with younger students. You’ll need two small cardboard boxes or cylinders, tape, scissors or a mat knife, heavy duty aluminum foil, tracing paper or vellum, and a pushpin.

Artist as Observer

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES

Dawoud Bey’s Birmingham Project addresses the history of the tragic day, September 15, 1963, in Birmingham Alabama, when six young African Americans were killed in acts of racial violence—four girls in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church and two boys in separate but related incidents. The series of black-and-white diptych photographs pair portraits of African Americans the same ages as the victims of the 1963 killings with pictures of adults at the ages that the victims would have been in 2012.

a. Ask students to look closely at Bey’s photographs on page 12 and compare the sitters. What do they notice about these people? What kind of expressions do they have? How are they posing? How would students describe their gestures? What are they wearing? What is similar or different about them? If they could speak, what do you think they would say? Why do you think Bey might have chosen to reflect upon a past incident by photographing people today? Ask your students to use the resources below to research and discuss Bey’s Birmingham Project and the events that took place in 1963. What specific information had an impact on your students? Compare the Birmingham events of the 1963 to current civil rights issues such as discrimination, affirmative action, same-sex marriage, and immigration.

http://www.dawoudbey.net/index.php/photographs/the-birmingham-project/

The Birmingham Project photographs on Dawoud Bey’s website.

http://www.artsbma.org/exhibition/dawoud-bey-the-birmingham-project/

The Birmingham Project exhibition at the Birmingham Museum of Art, September 8-December 2, 2013.

http://www.dawoudbey.net/index.php/information/recent-articles—publications/

Articles about Bey’s Birmingham Project.

http://www.democracynow.org/2013/9/17/the_fifth_little_girl_birmingham_church

Interview with Sarah Collins Rudolph.

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/randall/birmingham.htm

Birmingham, Alabama and the Civil Rights Movement in 1963.

Ask students to choose a local, national, or international current event and brainstorm five questions they would like to ask an adult and a peer about the event. Have students interview an adult and a peer, and record or write down their responses to the questions. Share the interviews with the class. Were their interviewees’ responses similar or different? In what ways?

IMAGES & RELATED INFORMATION

DAWOUD BEY

MAXINE ADAMS AND AMELIA MAXWELL (FROM THE BIRMINGHAM PROJECT), 2012

In 2005, Dawoud Bey began regularly visiting Birmingham, Alabama, where he familiarized himself with the city, its residents, and the history of the tragic day in September 1963 when six young African Americans were killed in acts of racial violence—four girls in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church and two boys in separate but related incidents. Seven years later, at the invitation of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Bey produced a series of black-and-white diptychs, two of which are on view in the 2014 Biennial, pairing portraits of African Americans the same ages as the victims of the 1963 killings with pictures of adults at the ages that the victims would have been in 2012.

The project is in part Bey’s response to seeing, almost fifty years earlier, a black-and-white photograph of bombing survivor Sarah Jean Collins, confined to a hospital bed, her face mangled. The image had immediately gripped the young Bey, who, as an African American child, understood that it could have been him lying there. When he returned to Birmingham to produce these new photographs, Bey staged his portraits in two locations—the Bethel Baptist Church, which occupied a central role in the Civil Rights movement, and the Birmingham Museum of Art, which in 1963 instituted a weekly “Negro Day” when African Americans were allowed to view its exhibitions.

DAWOUD BEY

B. 1953

Born and raised in Jamaica, Queens, New York, Dawoud Bey attended the School of Visual Arts in New York from 1976 to 1978 and received his BFA from Empire State College, State University of New York, in 1990 and his MFA from Yale University School of Art in 1993. Bey’s first major photographic project was Harlem USA (1975-1979), a collective portrait of the neighborhood. For four years, he roamed the streets of Harlem, photographing residents with a 35mm camera his godfather, Artie Miller, had given him when he was fifteen years old. Inspired by the work of earlier photographers, especially Walker Evans, Aaron Siskind, and Roy DeCarava, Bey continued to practice street photography in Harlem and other African American communities until the late 1980s, when he became concerned about what he described as the “implicit power relationships acted out in the process of photographing people, particularly those on the margins of society.” To address this problem, Bey dispensed with the unobtrusive snapshot camera and instead used devices that necessitated a conscious interaction between photographer and subject. He first employed a 4” x 5” view camera in 1988 and subsequently started working with a larger, tripod-mounted Polaroid camera. Since the Polaroid camera produced both a negative and a print, Bey decided to give the black-and-white positives to the people he photographed, keeping the negative for his own enlarged prints.

In 1991, Bey shifted his practice into the studio, using a 20” x 24” Polaroid camera to create large-scale, color close-ups of his sitters. Each complete work is composed of two to three images—arranged as diptychs or triptychs—taken at different angles in slightly modified poses, which highlight the singularity of his subjects. Since 1998, Bey has been professor of art at Columbia College in Chicago. He continues to work on community-based projects, including a series titled Class Pictures (2002-2007), in which he photographed high school students in the cities of Detroit, New York, Orlando, and San Francisco. Bey’s series Strangers/Community (2010-2013) brings together pairs of people who live in the same community, but who did not know each other before posing for the photographer.

Barry Schwabsky. “Redeeming the Humanism in Portraiture,” The New York Times, April 20, 1997, Section 13. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/20/nyregion/redeeming-the-humanism-in-portraiture.html

SHEILA HICKS

PILLAR OF INQUIRY/SUPPLE COLUMN, 2013-14

This cascading installation is one of the most massive produced by Sheila Hicks since she began working with textiles, or “supple materials” as she refers to her media, in the late 1950s. As with many of her large scale works, Hicks designed the piece with the architecture of the building in mind. Of interest to her are the coffered, open design of the ceiling and the sense of solidity she found in the stone floor. By extending the cords from the ceiling to the floor, she hopes to activate viewers’ awareness of these architectural elements.

Originally trained as a painter, Hicks became interested in global textile traditions, particularly in South America, and went on to develop her distinctive merger of painting, sculpture, drawing, and weaving. For her, the way the richly colored lines of her pieces move and intersect is a form of drawing in three dimensions.

SHEILA HICKS

B.1934

Born in Hastings, Nebraska, Sheila Hicks studied painting and color with artist Josef Albers at Yale University Art School, and saw the textile work of his wife, Anni Albers while she was a student. Hicks received her BFA in 1957 and her MFA in painting in 1959. Upon completing her studies, she traveled to Chile for a year on a Fulbright scholarship to paint. While in South America, she journeyed through Venezuela, Bolivia, Peru, Chile, and Mexico and developed an interest in working with fibers. After spending six months in Paris, Hicks settled in Mexico in 1960 and began making textiles, improvising four-post looms by turning tables upside down. She also taught architecture students design and color at the Universidad Autonoma in Mexico City. In 1964 Knoll Designs offered Hicks contracted work and she moved to Paris where she continued to make her own work on a small scale and established a studio in the Latin Quarter. She has assisted with the production of textiles in India, South Africa, and Morocco as well.

Hicks is renowned as a pioneer in the fiber arts revolution of the 1960s that sought to transform textiles into a three dimensional art form. In the mid-1960s, she found a way to make large-scale wool panels with a pneumatically driven tufting tool at a factory in Germany. She received her first commission for an architectural project from the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1968 and she has collaborated with businesses and architects. Since the 1960s, Hicks has created monumental sculptures and installations as well as miniatures and whimsical soft stones that employ both loom and non-loom methods. The miniatures are woven on small frame looms and provide for the creative exploration of traditional and non-traditional techniques. Her architectural commissions are often large-scale and account for a large segment of her professional endeavors. Hicks divides her time between Paris and New York.

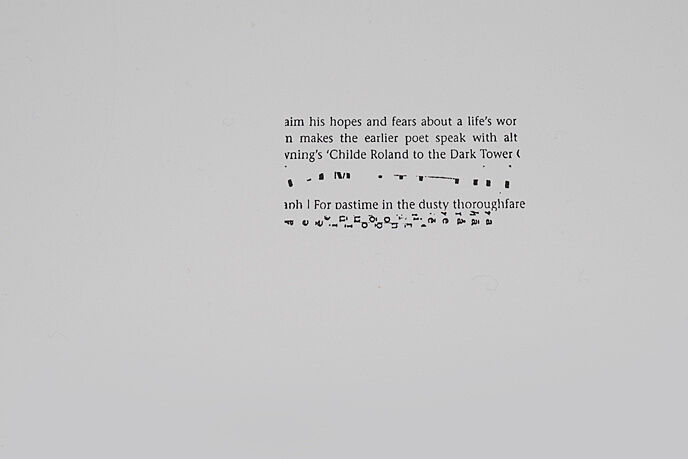

SUSAN HOWE

UNTITLED (FROM TOM TIT TOT), 2013

Susan Howe’s poems on view draw on a wide variety and range of texts, spanning American, British, and Irish poetry and folklore, as well as critical and art historical sources. Howe begins with copies of the source material, which range from excerpts from the texts themselves, as well as the footnotes, table of contents, and marginalia. From these sources, she cuts out sentences and fragments, pasting and taping them back together but retaining the typefaces, spacing and rhythms of the original source. These compositions, built both by control and chance arrangements, are then transferred into letterpress prints, resulting in poems that are physically imprinted, carved into the paper support. The edges between sources disappear in the final version, resulting in poems that are at once legible and illegible, sitting in a space between writing and seeing, reading and looking. For Howe, “the bibliography is the medium.”

Displayed for the first time in an exhibition, Howe’s letterpressed poems are shown in pairs, as they would be in a book, their ultimate destination.

SUSAN HOWE

B. 1937

Writer, essayist, and poet Susan Howe was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Her mother Mary Manning was an actress and her father a law professor at Harvard; her sister, Fanny Howe, is also an acclaimed poet. After graduating from high school, Howe spent a year in Dublin, as an apprentice at the Gate Theatre. She earned a degree from the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts in 1961, and enjoyed some success with exhibitions in New York.

Howe’s work is often associated with the experimental approaches and disregard for conventional literary forms of the Language School, emergent in the 1970s. But her combination of formal invention and historical consciousness also recalls modernists like James Joyce and William Carlos Williams as much as her younger contemporaries. She is deeply invested in American history, from the Revolutionary era through World War II, as well as American, British and Irish literature. Her work layers all of these archives, weaving together disparate ways of reading, looking and thinking into poems complicated by the compressed idioms, emotions, histories and transcriptions held in place by her combinations and cuts. Howe explores the word as shape, image, and sound, plays upon words that possess phonetic similarities. Some critics have likened her poems to paintings on the page, the large gaps between words providing white spaces that are meant to convey as much meaning as the words themselves. We ar e asked to see and hear the shapes and sounds of the words instead of just reading through them to interpret their meaning.

One of the preeminent poets of her generation, Howe is the author of several books of poems, essays, and two volumes of criticism. Recent publications include Sorting Facts, or Nineteen Ways of Looking at Chris Marker (2013), That This, (2010), and a new edition of My Emily Dickinson (1985, reissued 2007), an in-depth examination of Dickinson as a nineteenth-century woman poet in an era of constriction and conformity. Howe has received numerous honors and awards for her work, including two American Book Awards from the Before Columbus Foundation and a Guggenheim fellowship. She has been a distinguished fellow at the Stanford Institute for Humanities, and the Anna-Maria Kellen Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin. From 1991-2006 she taught at the State University of New York-Buffalo, where she held the Samuel P. Capen Chair of Poetry and the Humanities.

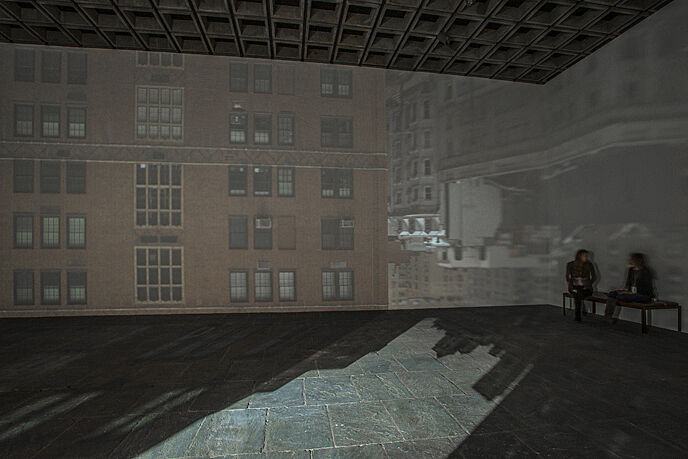

ZOE LEONARD

945 MADISON AVENUE, 2014

Zoe Leonard has transformed a section of the Museum’s fourth-floor gallery, with its signature Marcel Breuer–designed window, into an enormous camera obscura, drawing attention to both the Museum’s building and the city outside.

The camera obscura is a naturally occurring phenomenon recorded since ancient times, in which a small hole in one side of a dark chamber projects an inverted image of the outside view onto the surfaces of the room. Leonard takes up this principle in order to investigate vision as not only an optical process but also a temporal and social experience; she places us directly inside the camera, engaging with the apparatus of sight itself.

In a series of related camera obscura installations begun in 2011, the artist has sited works in a range of locations, each calling to mind a different set of associations and references. On the occasion of the Biennial, Leonard looked to notes that Breuer made as he designed the Museum’s building in 1965. Of the building, he wrote, “It should be an independent and self-relying unit, exposed to history, and at the same time it should have visual connection to the street”; and, “Windows have lost their justification of existence in this building; only a very few remain, and only to establish a contact with the outside.”

Leonard’s installation invites us to slow down. On entering, the viewer may barely perceive the image; the room might appear to be completely dark. But as one’s eyes adjust, the picture becomes increasingly apparent, growing brighter and revealing color and detail. Simultaneously, the image evolves: the light shifts, blinds open and close, cars drive up Madison Avenue—all projected onto the building’s gridded cement ceiling. The viewer is immersed in a continuous present, watching and listening, as much a part of the installation as is the view outside.

ZOE LEONARD

B. 1961

Born in Liberty, New York, Zoe Leonard grew up in New York City. At the age of fifteen, she dropped out of school and taught herself how to take photographs with her mother’s camera. Her early images often reflect her peripatetic life traveling across the country, working at odd jobs, and encountering various landscapes. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Leonard continued to photograph urban scenes in cities such as Paris and Washington, D.C.; she also captured Niagara Falls and anonymous suburban housing developments. In addition, she began taking photographs concerning the representation of women. In one series, she shot catwalk models from a low angle, revealing their underwear; in others, she depicted anatomical models, wigs, chastity belts, and female dolls, alongside the bell jars, receptacles, and vitrines used to display them in medical, natural history, and art museums.

Beginning in the late 1980s, Leonard worked with Act Up and other artist collectives engaged in activist projects on behalf of HIV/AIDS and gay rights, including Gang and Fierce Pussy. After the 1992 death of her close friend and fellow artist David Wojnarowicz from complications of AIDS, Leonard mounted an exhibition entitled Strange Fruit (For David) (1995), in which she sewed together the skins of 295 pieces of discarded fruit and decorated them with wire, buttons, and thread. In 1995, Leonard traveled to Alaska, where she spent two years in solitude, and to which she has returned repeatedly. From these experiences, she produced works about endurance and survival, like Tree and Fence, Out My Back Window (1998), shot in New York, which shows a tree, bisected by a fence and strewn with litter, growing despite such unlikely circumstances. Leonard undertook an ambitious project that came to be known as Analogue (1998-2007) that she completed with a Rolleiflex camera. Comprising approximately 400 images taken in New York and places that she visited in Europe and Africa, Analogue documents the disappearance of local markets and individual businesses as the result of an expanding global economy. Leonard presented the project both in a book format, pared down to ninety-two images, and as a museum display, in which the New York pictures are paired with images of storefronts from around the world in a grid format. Leonard’s more recent projects involve found photographs and postcards and a series of camera obscura installations that examine the processes of producing and looking at images.

KEN OKIISHI

GESTURE/DATA, 2013

Ken Okiishi’s work reveals a fascination with the translation and migration of meaning and material in a world gone digital. His recent series of hybrid works—neither strictly paintings nor exclusively videos—derive from his experience of viewing a large abstract painting by Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) at the Museum of Modern Art. Taking a picture of the work with his cell phone, he was intrigued by the immediate impact that making the photograph had on the painting as it lost its scale and materiality to a small, portable field of glowing pixels and code. The resulting series, gesture/data, connects the surfaces, screens, and gestures that paradoxically link the techniques of gestural painting with the swipes, taps, pinches, and drags that characterize the way we interact with contemporary technology. Okiishi has created this series of paintings directly on the surfaces of flat-screen televisions playing mash-ups of old analog home VHS recordings of TV shows partially recorded over with sequences from new, digitally broadcast television. Binding together the painterly trace of a brushstroke with multiple generations of electronically recorded media-derived image flows, Okiishi produces unstable, glitchy image-objects that, with a degree of humor, highlight the fragility and absurdity of our attempts to document human presence—while at the same time affirming that presence.

KEN OKIISHI

B. 1978

Ken Okiishi was born in Ames, Iowa, and received his BFA from The Cooper Union,New York in 2001. He employs video, performance, and installation to create works that convey the moments when language and images begin to fall apart and there are breakdowns in communication. In his videos, Okiishi uses the language and musical structures of existing movie scripts and scores as a point of departure to uncover the dissonances of memory formation and contemporary culture.

Okiishi has explored subjects such as the psychogeography of New York and Berlin and global data streams. In (Goodbye to) Manhattan (2010), Okiishi reimagines Woody Allen’s film, Manhattan and explores New York’s perception of Berlin as a utopian center of art production. The script is the Google translation into English of the German version of Allen’s original film. In Okiishi’s words: “This is, on the one hand, an autobiographical reality (I’ve been going back and forth between Berlin and New York for the last nine or so years); it is also an often fraught channel of cultural exchange.” In The Very Quick of the Word (2013), Okiishi examines human memory by way of gestural paintings and unstable video recordings played on VHS tapes. Okiishi has frequently collaborated with his partner, the artist Nick Mauss.

Quoted in Michael Sanchez, “From the Inside Out: Ken Okiishi,” Art in America, February 17, 2010.

http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/from-the-inside-out-ken-okiishi/

Bibliography and Links

Whitney Biennial 2014. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2014.

http://www.dawoudbey.net/index.php/photographs/the-birmingham-project/

The Birmingham Project photographs on Dawoud Bey’s website.

http://www.artsbma.org/exhibition/dawoud-bey-the-birmingham-project/

The Birmingham Project exhibition at the Birmingham Museum of Art, September 8-December 2, 2013.

http://www.dawoudbey.net/index.php/information/recent-articles—publications/

Articles about Bey’s Birmingham Project.

http://www.democracynow.org/2013/9/17/the_fifth_little_girl_birmingham_church

Interview with Sarah Collins Rudolph.

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/randall/birmingham.htm

Birmingham, Alabama and the Civil Rights Movement in 1963.

http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-sheila-hicks-11947

Oral history interview with Sheila Hicks, 2004 Feb. 3-Mar. 11, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/susan-howe

Susan Howe on the Poetry Foundation’s website.

http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/6189/the-art-of-poetry-no-97-susan-howe

Susan Howe, The Art of Poetry No. 97, interviewed by Maureen N. McLane, Paris Review.

http://www.camdenartscentre.org/whats-on/view/exh21#9

Zoe Leonard’s camera obscura at the Camden Arts Centre.

http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/zoe-leonard-murray-guy/

Courtney Fiske, “In-Camera: Q+A with Zoe Leonard,” Art in America, November 6, 2012.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

A special area of the Whitney’s website with resources and activities for artists ages 8-12.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; Heather Maxson, Manager of School, Youth, and Family Programs; and Ai Wee Seow, Coordinator of School and Educator Programs.

Programs are made possible by endowments from the William Randolph Hearst Foundation and the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Fund.

Additional support is provided by Con Edison, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools endowed by the Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.