Teacher Guide:

An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney's Collection, 1940–2017

Aug 18, 2017

WELCOME TO THE WHITNEY!

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017, on view at the Museum through Spring 2018. The exhibition explores how artists from the 1940s to the present have confronted the political and social issues of their day.

Recommended for grades 6–12, this teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team

An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from The Whitney's Collection, 1940–2017.

Through the lens of the Whitney’s collection, An Incomplete History of Protest looks at how artists from the 1940s to the present have confronted the political and social issues of their day. Whether making art as a form of activism, criticism, instruction, or inspiration, the featured artists see their work as essential to challenging established thought and creating a more equitable culture. Many have sought immediate change, such as ending the war in Vietnam or combating the AIDS crisis. Others have engaged with protest more indirectly, with the long term in mind, hoping to create new ways of imagining society and citizenship.

Since its founding in the early twentieth century, the Whitney has served as a forum for the most urgent art and ideas of the day, at times attracting protest itself. An Incomplete History of Protest, however, is by name and necessity a limited account. No exhibition can approximate the activism now happening in the streets and online, and no collection can account fully for the methodological, stylistic, and political diversity of artistic address. Instead, the exhibition offers a sequence of historical case studies focused on particular moments and concepts—from questions of representation to the fight for civil rights—that remain relevant today. At the root of the exhibition is the belief that artists play a profound role in transforming their time and shaping the future.

An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017 is organized by David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Collection; Jennie Goldstein, assistant curator; and Rujeko Hockley, assistant curator; with David Kiehl, curator emeritus; and Margaret Kross, curatorial assistant.

More information:

Pre-Visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. We have included some selected images from the exhibition, along with relevant information that you may want to use before or after your Museum visit. You can print out the images or project them in your classroom.

Pre-visit Objectives:

Introduce students to the artists and works in the exhibition.

- Examine themes students may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how artists have used art as a form of protest.

- Examine different styles of and approaches to art as a means of protest.

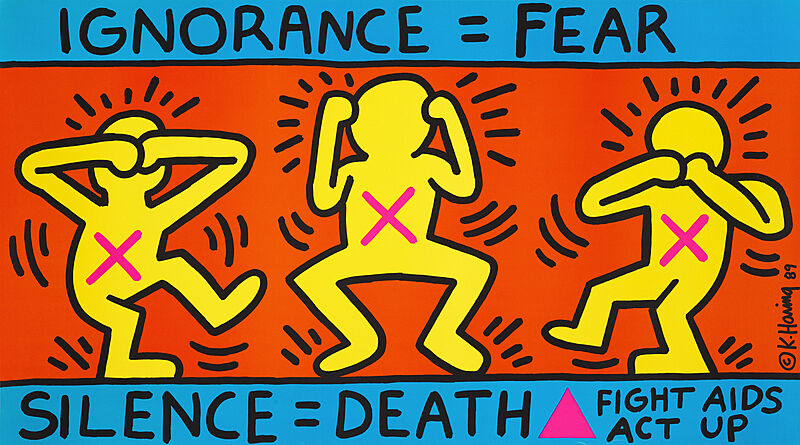

Keith Haring

Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death, 1989

During the 1980s and 1990s, AIDS and complications from it killed nearly half a million people in the United States, a disproportionate number of them gay men and people of color. AIDS became one of the most searing issues in American life and politics. The artistic community lost thousands; still more friends, lovers, and family members faced lives transformed by grief, fear, indignation, and illness. The activist and critic Douglas Crimp argued that both “mourning and militancy” were required to address the AIDS crisis.

Many artists made activist work that criticized government inaction, promoted awareness and treatment, and expressed support for people fighting and living with the virus. Often adopting the visual strategies of previous protest movements, artists mobilized against AIDS by deploying a sophisticated understanding of media culture, advertising, and product branding. Their widely distributed posters, artworks, and graphics were often used at marches and rallies or were posted on the street.

Keith Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987 and two years later, he completed one of his most widely recognised posters. He was determined to give a voice to those who felt silenced during this period and used the pink triangle that had been reappropriated by the LGBT community after being used in the Holocaust to identify gay people.

Artist as Critic

Protest

a. With your students, brainstorm what the word protest means. In twentieth and twenty-first century America, discuss what people have protested for and against, and the forms that their protests have taken. For example, marches, rallies, demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, letter-writing, petitions, posters, sit-ins, occupying spaces, and social media.

b. What current political, social, or cultural issues do students connect with protest? Ask each student to reflect on and write briefly about an issue that they have protested or wanted to get more involved with. Have students describe how they would want to get involved. Ask for student volunteers to share and discuss their writing with the class. Were students’ issues local? National? International? Were the issues new, longstanding, or ongoing? Did any students choose the same issues?

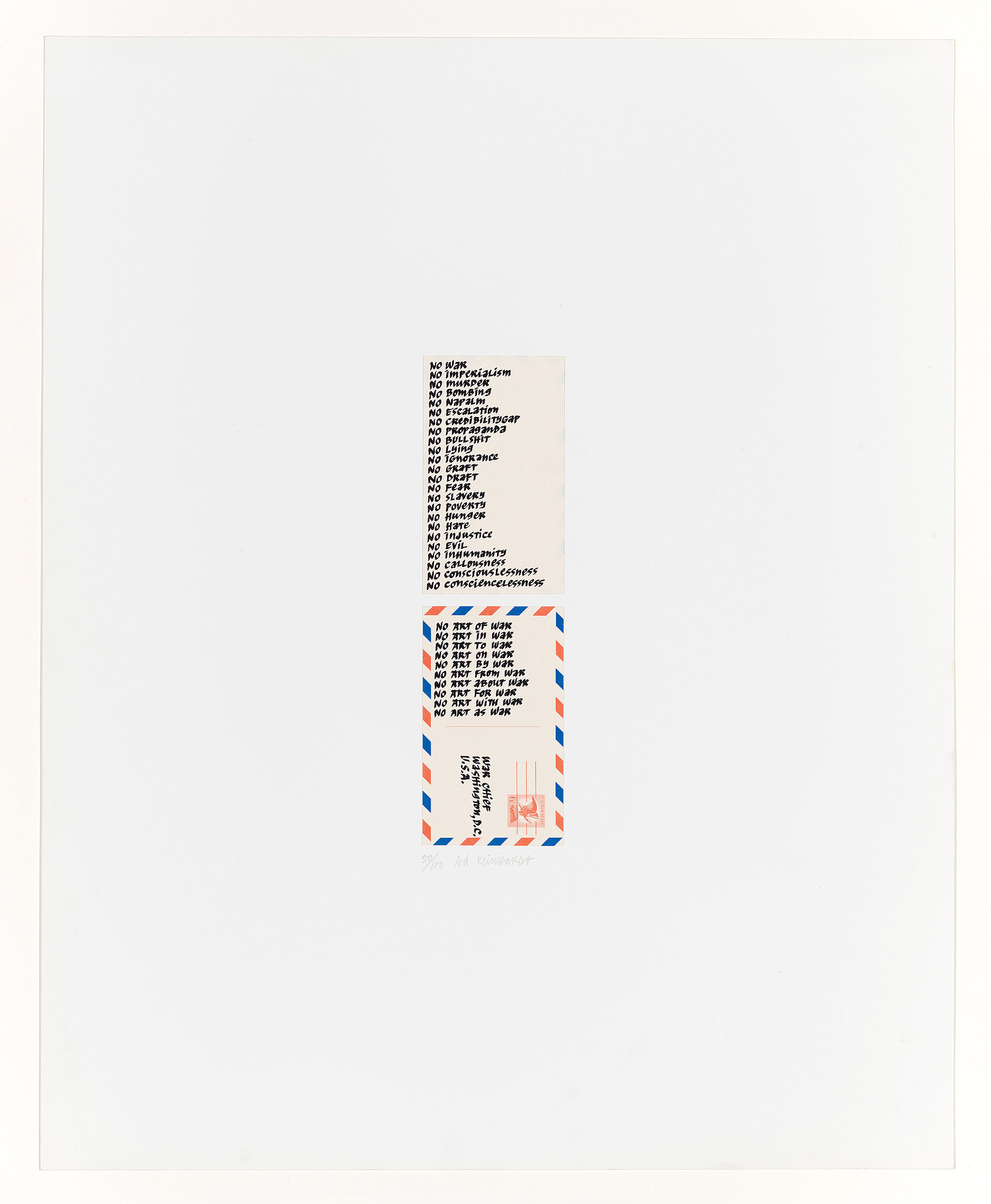

Ad Reinhardt

No War, 1967

No War (1967) was Ad Reinhardt’s contribution to a portfolio released by Artists and Writers to protest the Vietnam War. It is a standard-issue postcard, inscribed on both sides and addressed to the “War Chief” in Washington, D.C. By the late 1960s, Reinhardt was known not only as an important abstract painter but as an incisive critic of art world pretensions and pieties, and in No War he turned his critical eye on politics using the rhetoric of negation that he had developed in his writings on art. On one side of the card is a list of negative orders, some specific to Vietnam (“no napalm,” “no credibility gap”), others applicable to any armed conflict ("no bombing," "no draft," "no escalation"), and still others commands of a general ethical or moral sort (“no poverty,” “no injustice,” “no evil”). Reinhardt’s repetition is strident and unequivocal; it presents no argument and leaves no room for ambiguity. And while the text on the facing side of the postcard, which addresses the role of art in protest, seems to share this certitude, its consequences are less categorical. By declaiming “no art in war” and “no art on war,” Reinhardt seems to be denying the value of or need for art as a means of resistance—yet No War is itself a work of protest art. This inconsistency suggests the conflicted position in which many artists found themselves in the 1960s: anxious to add their voices to a growing chorus of dissent, but often unsure about what form their protest should take and how effective it could be.

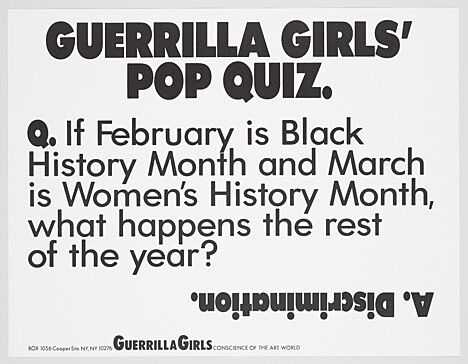

Guerrilla Girls

Guerrilla Girls' Pop Quiz, 1990

Beginning in the 1960s, the feminist movement grew increasingly vocal and influential. Advocating for the legal and social rights of women, it addressed reproductive freedom, domestic and sexual violence, and the family, among other pressing concerns. The feminist slogan “the personal is political” became both rallying cry and directive in this period for many artists, both male and female, who often used video and photography to give visibility to their lived experiences.

The Guerrilla Girls is an anonymous group of feminist, activist artists who formed in New York City in 1985 with the mission of exposing the unequal status of women as art workers and fought for the inclusion of women and people of color in major art institutions. The group employs culture jamming in the form of posters, books, billboards, and public appearances to expose discrimination and corruption. They have staged demonstrations and alternative exhibitions, drop-lifts in exhibition shops and other ways of communicating their message. Members wear gorilla masks when they make public appearances and use pseudonyms, adopting the names of deceased female artists. They remain anonymous, stating that issues matter more than individual identities. Referring to themselves as ‘The conscience of the artworld,’ the Guerrilla Girls have continued to place pressure on art dealers and major arts organisation to be accountable for the inequity of their collection and exhibition strategies. Their protest is ongoing.

Artist as Critic

Art as a form of Protest

a. Ask students to think about billboards, posters, graffiti, or placards—either that they have seen or made themselves—that include visual imagery. Compare protest formats with images and without images. How effective are forms of protest that include visual imagery? What impact do they have?

b. With your students, brainstorm why art might have advantages or challenges compared with other forms of protest. How might an artwork connect with its potential audience in ways that are different from other types of protest?

Edward Kienholz

The Non-War Memorial, 1970

Edward Kienholz’s The Non War Memorial was made in 1970, as the United States entered a new decade still engaged in war in Southeast Asia. By that year, more than 48,000 members of the U.S. military had died while serving in Vietnam. In this work, five military uniforms stuffed with sand lay strewn on the floor as if they are dead bodies. Part of a series that Kienholz called Concept Tableaux, it functions as both a stand-alone artwork and a proposal for a larger project. The unrealized project called for filling a field in Clark Fork, Idaho, with 50,000 of these uniforms, filled with clay, that eventually would rot, decompose, and return to wild flowers and alfalfa—a bracing repudiation of the war and its consequences. There would be nothing left, nothing to visit, nothing to memorialize.

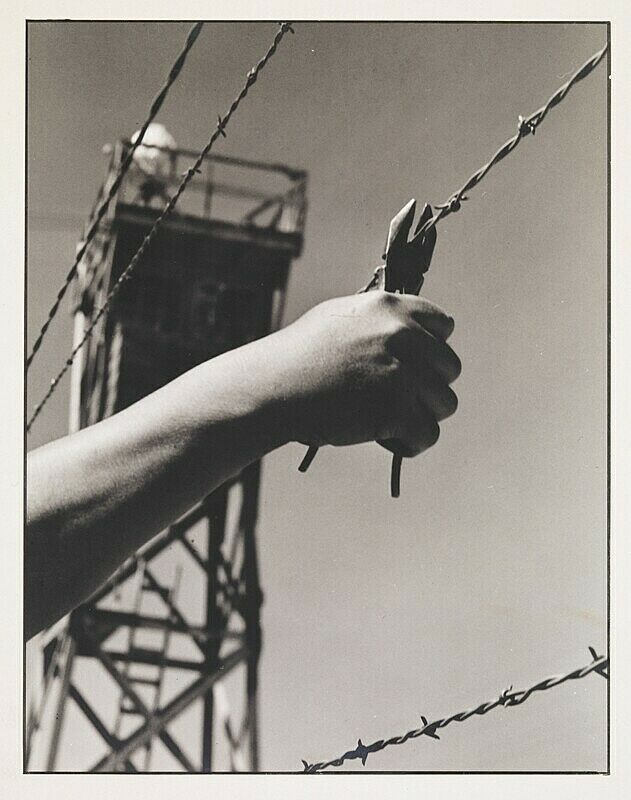

Toyo Miyatake

Untitled, 1944

Toyo Miyatake began his photography career in 1909, shortly after immigrating to Los Angeles from Japan. In 1942, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States’s declaration of war on Japan, Roosevelt authorized the relocation of over 100,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps. Miyatake and his family were forced from their home and taken to a camp in Manzanar, California. As photography was outlawed there, Miyatake smuggled in a lens, built a makeshift box camera, and began surreptitiously documenting life at Manzanar. He was eventually discovered but was allowed to continue shooting, due in part to the support of his friend Ansel Adams, who had photographed the camp as a visitor.

Artist As Critic

The Meaning And The Message

American artists in the mid-twentieth century used ideas of refusal and resistance to reject inherited policies, politics, and social norms. For some, like Toyo Miyatake, the very act of making art was a form of disobedience. He documented his internment by smuggling camera parts into the camp in Manzanar, California, where he and other Japanese Americans were held during World War II.

a. Ask students to choose one of the images. Have them divide into small groups. Ask each group to look closely and discuss their selected image using the questions below. Have them take notes about their discussion.

- What is communicated immediately by this image?

- What questions do students have about its significance or resonance?

- Does the image conjure a specific moment in time?

- How does it resonate with current issues that are being protested?

- What outside knowledge or understanding might the artist be relying on to communicate this message to the viewer?

b. Share some of the information about these works with each group. How does this information change students’ perception of the message and meaning of these artworks?

c. Have each group present and discuss their interpretations of the artwork they selected. In what ways did students interpret the message and meaning of the artworks?

Artist As A Critic

Protest Now

Artists today are looking to the past to understand their present as well as to explore the possibilities—and the possible failure—of collective action. Artworks in the exhibition largely made after the year 2000 evoke the “usable past,” the concept that a self-conscious examination of historical figures, moments, and symbols can shape current and future political formation.

a. Ask student groups to look at the images and discuss the choices that the artists made to convey their points of view. Based on this discussion, ask each student to find an image about a current issue that is important to them. How would they change one thing to convey their ideas about the issue? For example, changing a detail or part of the image, text, or medium.

Post-visit Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artists’ ideas through discussion, art-making, and writing activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask your students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Senga Nengudi

Internal I, 1977

Made from nylon hosiery, a material that strongly suggests skin, Nengudi’s Internal I (1977) evokes the resilience and fragility of the female body upon entering—and being defined by—society. Its bilaterally symmetrical form calls to mind a human figure that has been brutally stretched and flayed. In the artist’s words:

“It was sort of like nerve endings. I took it to that level of extremeness, stretching it as far as it tolerated. And with the pantyhose I was really interested in the elasticity of it, because we as human beings have a lot of elasticity, not only with our bodies—you know, dieting and gaining weight again and then doing this and doing that and you know the psyche—that also stretching and being able to come back into some form of normality.”

Melvin Edwards

Pyramid Up and Down, 1969 (Prefabrication 2017)

Constructed from barbed wire, Melvin Edwards’s Pyramid Up and Down (1969) was included in his one-person exhibition at the Whitney in 1970. This dangerous material connotes prisons, animal pens, and physical pain within the vocabulary of minimal sculpture.

The artist David Hammons remarked of Edwards’s work in the 1970 Whitney exhibition:

“That was the first abstract piece of art that I saw that had cultural value in it for Black people. I couldn’t believe that piece when I saw it because I didn’t think you could make abstract art with a message.”

Edwards himself said:

“All systems have proven to be inadequate. I am now assuming that there are no limits and even if there are I can give no guarantees that they will contain my spirit and its search for a way to modify the spaces and predicaments in which I find myself.”

Theaster Gates

Minority Majority, 2012

Theaster Gates began using decommissioned fire hoses in his sculptures in 2011. Here referencing the violent use of the fire hose against peaceful civil rights protesters in the early 1960s, Gates frequently engages materials that speak to histories of race in the United States. Gates has said of this series:

“I’d been thinking what I could do to jar people’s memory about this history without making it kitsch or a cheap shot. And I remembered all those interesting moments when you start to think you’re doing all right, when somebody will remind you that you’re still a nigger. I’m not immune to the problems that Black people faced in the ’20s, ’30s, [and] ’50s.”

Artist as Critic

The Message in the Material

Artists in the exhibition have used a variety of non-traditional materials to create their works, including firehose, pantyhose, military uniforms, and barbed wire. Working abstractly, Senga Nengudi and Melvin Edwards explore how materials and space can be considered in relation to gender and race. Theaster Gates used decommissioned fire hoses from the 1960s to reference racism during the civil rights movement of the 1960s and in contemporary American life.

a. Using the artworks by Gates, Nengudi, and Edwards, ask students to discuss the symbolic, literal, and contextual significance of materials in everyday life as well as in protest situations. For example, barbed wire is used to keep people in or out of certain spaces or territories.

b. Discuss why the artists might have chosen these specific materials for their artwork. Talk about how they have manipulated the materials in ways that prompt us to reconsider their meaning.

c. Divide students into small groups. Ask your students to think of a material from today’s culture that might be manipulated or repurposed as a visual form of protest. How would students transform that material? Ask each group to brainstorm and take notes.

d. Ask student groups to propose how they would transform their chosen material. Make sketches or write a description. To extend the activity, have student groups create their own protest artwork out of the material they proposed to use.

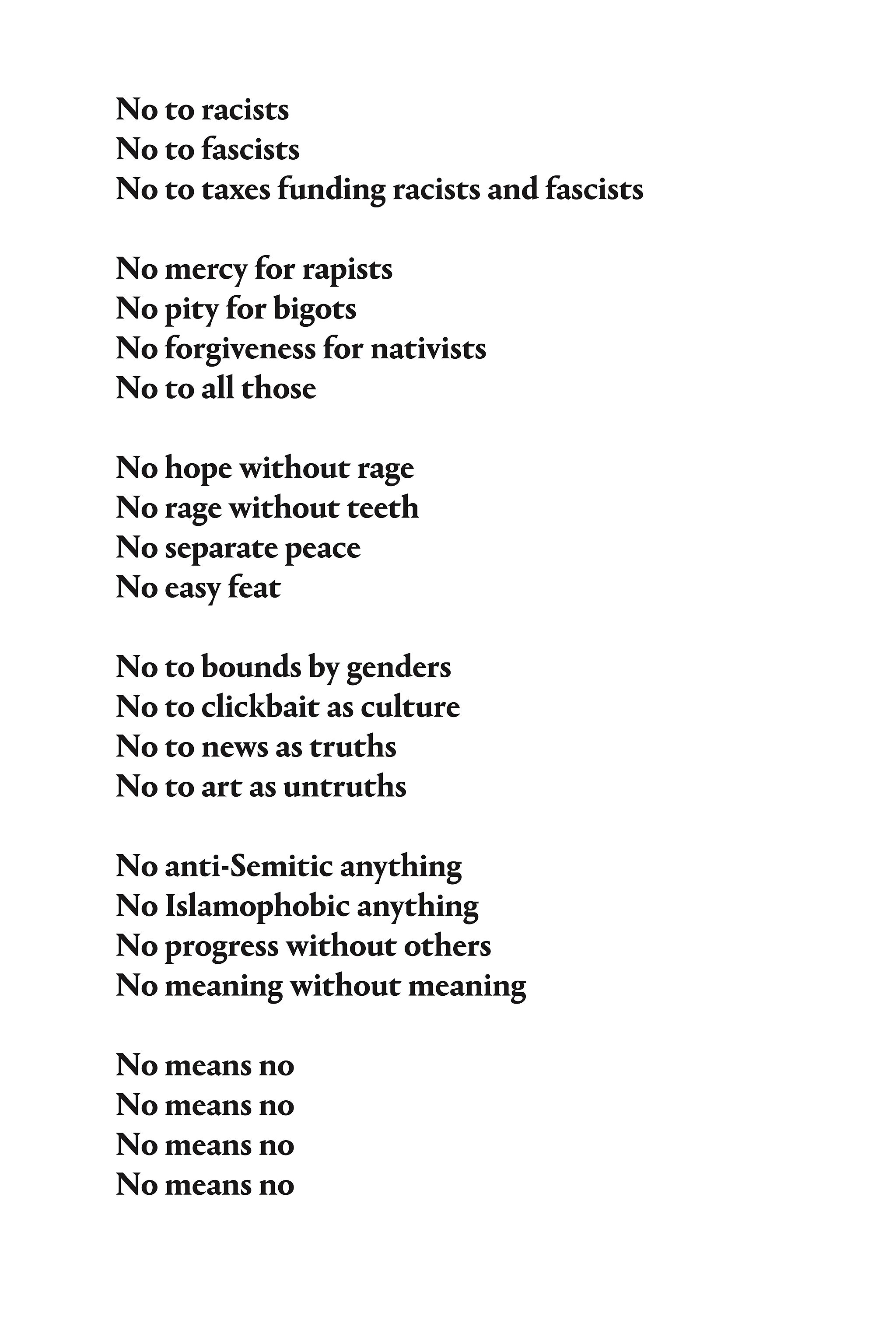

Badlands Unlimited

New No's: This Kill Fascists, 2016

Founded by Paul Chan in 2010, Badlands Unlimited publishes e-books, paper books, and artist works in digital and print forms. Taking a cue from Ad Reinhardt’s No War (1967), New No’s is a poem written by the collective after the 2016 election. Badlands Unlimited have said that this post-election response “acts as a declaration against the drift of American society toward what is most un-American.”

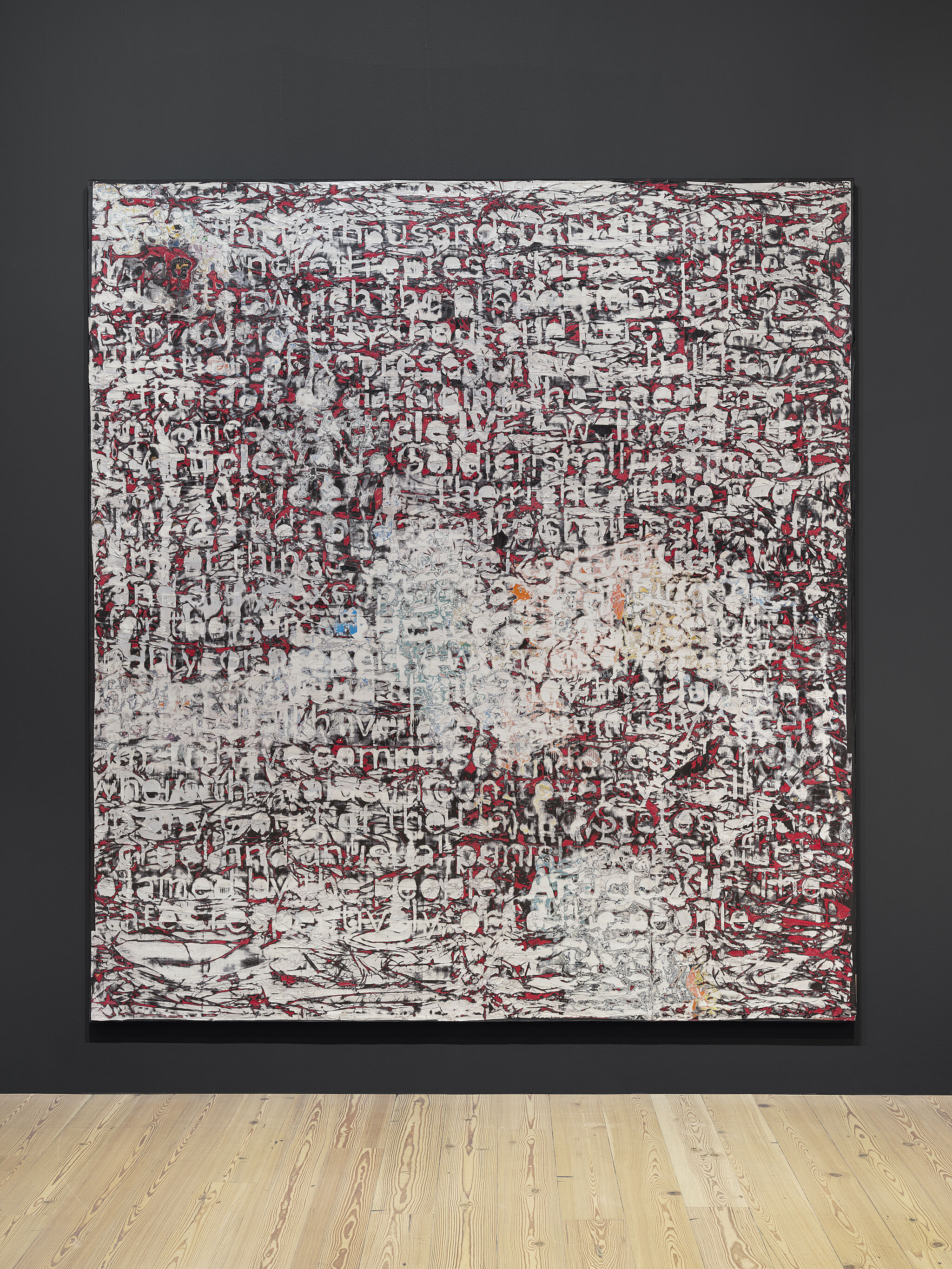

Mark Bradford

Constitution III, 2013

While initially resembling a purely abstract painting, Mark Bradford’s Constitution III (2013) contains actual excerpts from the United States Constitution. His embedding of this language within an aggressively worked surface suggests that the historic document is also a living one, subject to modification, reinterpretation, and debate.

Carl Pope

Some of the Greatest Hits of the New York City Police Department: A Celebration of Meritorious Achievement in the Community, 1994

In this installation, Carl Pope addresses the history of police brutality in New York between 1949 and 1994. Awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993, Pope began looking into the New York Police Department's record of violent interactions with Black and Brown residents. Each trophy or plaque in this work memorializes a different event. The inscriptions, which include the names of the people who were killed or brutalized as well as the officers who committed the acts, were written by the artist.

Pope purchased the trophies from businesses that make them specifically for law-enforcement use, thus overlaying the histories of both police violence and the trophy industry. While some of the individual names and associated events were widely reported on at the time, others were—and remain—relatively unknown. Encompassing nearly five decades of violence, its impact has only been amplified in the more than twenty years since its creation and original display.

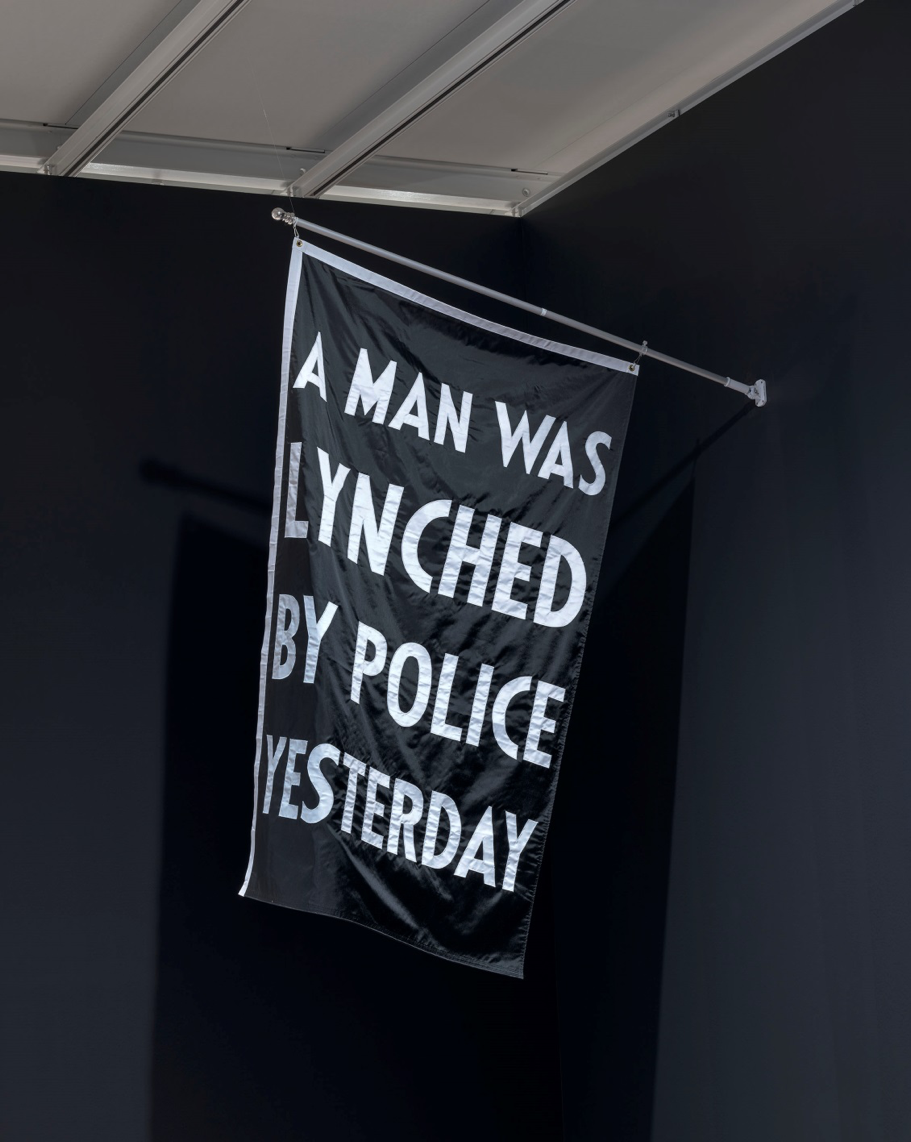

Dread Scott

A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday, 2015

Dread Scott made this banner in response to the police shooting and death of Walter Scott on April 4, 2015, in South Carolina. It recalls a flag that flew from the New York headquarters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1920s and 1930s every day after someone was lynched. The original banner read “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” and was part of the NAACP’s larger campaign against such violence. In the artist’s own words, “This artwork is an unfortunately necessary update to address a horror from the past that is haunting us in the present.”

Artist as Critic

Found Text

Badlands Unlimited, Mark Bradford, Carl Pope, and Dread Scott use text in their work, but they have changed it, written their own versions, or used a different medium than the orginal to create new meaning.

a. Look at these artists’ work. Explore and discuss the choices that these artists have made to create their works. Consider the texts that the artists invoke, appropriate, or emulate. Consider the diction, legibility, and title of each work.

- What is the tone of the work?

- How does the tone of the work relate to the font, color, form, scale, and word choice?

- How are the artists offering the viewer ways to interpret or overlay meaning in their work? To what effect?

b. Ask students to mine social media or news sources to find a text that they can invest with new meaning. Have them experiment with adding, subtracting, effacing, and changing scale, color, form, or wording. Students could print digital images and use collage, photography, drawing, painting, or a combination of these techniques to create an artwork.

c. Have students discuss their artworks and make a protest wall in their classroom.

Bibliography and links

Japanese Internment Camps

https://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/historyculture/japanese-americans-at-manzanar.htm

http://www.ht-la.org/htla/projects/oralhistory/japaneseinternment/life-in-manzanar.html

Vietnam War

http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-vietnam-war/home/

http://www.rationalrevolution.net/war/american_involvement_in_vietnam.htm

AIDS Crisis

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/sets/act-up-and-the-aids-crisis/

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/guides/teaching-guide-exploring-act-up-and-the-aids-crisis

Civil Rights Movement

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birmingham_campaign

http://bcc2.lunchbox.pbs.org/black-culture/explore/civil-rights-movement-birmingham-campaign/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCxE6i_SzoQ

Police Brutality

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCxE6i_SzoQ

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/08/19/us/police-videos-race.html?mcubz=1

Whitney Museum Resources

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; and Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, the Dalio Foundation, The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation, Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Barker Welfare Foundation, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee, and contributions from family and friends made in memory of Jill Buttenwieser Schloss.

Endowment support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick, Laurie M. Tisch, and Steven Tisch.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools are endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

Major support for An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940‒2017 is provided by The American Contemporary Art Foundation, Inc., Leonard A. Lauder, President.

Significant support is provided by the Ford Foundation.