Teacher Guide:

American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe

Dec 19, 2013

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

1. How can these materials be used?

These materials provide a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

2. Which grade levels are these materials intended for?

These lessons and activities have been written for Elementary, Middle, or High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs.

3. Learning standards

The projects and activities in these curriculum materials address national and state learning standards for the arts, English language arts, social studies, and technology.

4. Feedback

Please let us know what you think of these materials. How did you use them? What worked or didn’t work? Email us at schoolprograms@whitney.org.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s collection of early to mid-twentieth-century art offers a window into how artists in the United States channeled their diverse experiences as Americans into dramatic visual statements that mirrored the country’s changing sense of itself from the early part of the century to the postindustrial 1960s.

Vanguard artists in the United States during the first half of the century drew on stylistic innovations developed in Europe to forge a powerful modernist art inherently rooted in the American experience. With the nation’s growing prominence on the international stage after World War II, American artists redefined their relationship to Europe, taking the lead in aesthetic innovation while continuing to ground their art in their emotional and intellectual responses to the natural and man-made worlds that surrounded them. Although the work of the postwar artists differed stylistically from that of their predecessors, they nevertheless engaged with many of the same themes and subjects. Examples of such cross-generational affinities can be seen in the three middle rooms of this exhibition, highlighting the shared approaches these two groups took to abstraction, popular culture, and urban life.

American Legends is being refreshed continuously throughout its duration, with rotations of art as well as of individual artists. These rotations allow the museum to showcase its extensive holdings of a wide range of iconic and lesser-known artists of the twentieth century.

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the American Legends: From calder to O’Keeffe exhibition. You may want to introduce students to at least one work of art that they will see at the Museum. See the Images and Related Information section of this guide for examples of artists and works that may have particular relevance to the classroom.

Objectives:

Introduce students to the works of pre- and postwar American artists and compare how they represented the world around them in the early and mid-twentieth century.

Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit such as “Artist as Observer” and “Artist as Experimenter.”

Explore how artists have interpreted the modern world over time.

In the early twentieth century, American artists looked for new ways to depict what they saw around them and define an American art, distinct from its European counterparts. Some artists focused on the dynamism and novelty of the modern metropolis. Others represented modern life and nature using color, shapes, and abstract forms. After World War II, artists were inspired by changing American culture and the phenomena of contemporary life. In the center galleries of this exhibition, works by prewar and postwar artists are hung in pairs, highlighting the ways in which these artists looked at the world around them.

Artist as Observer

SLEUTH THE SCENE

In 1929, Edward Hopper and his wife Josephine traveled to Charleston, South Carolina. In the countryside surrounding Charleston, Hopper encountered a woman standing in front of her cabin. Amost a quarter of a century later, Hopper painted the scene, perhaps from sketches, or from his memory and imagination.

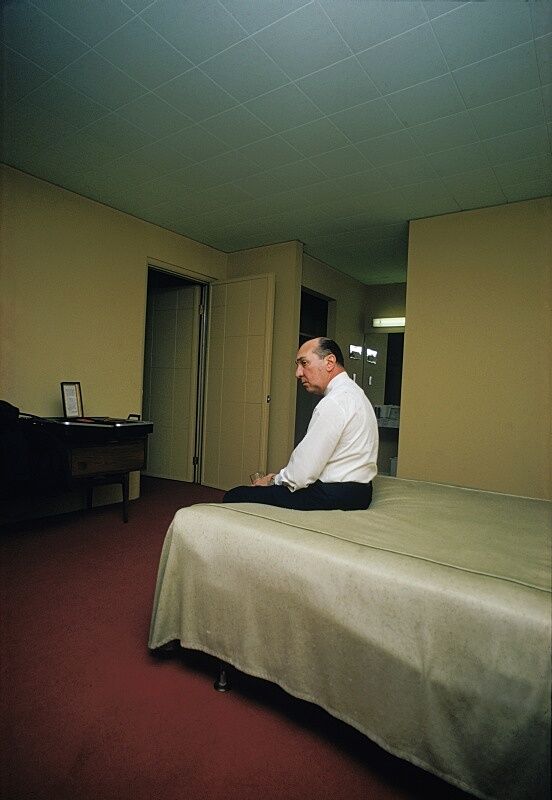

In the early 1970s, William Eggleston began to take road trips with curator Walter Hopps, leaving from Memphis, Tennessee and venturing as far as the Pacific Coast. While in Huntsville, Alabama, Eggleston photographed a man in what appears to be a hotel room. Each artist created a specific mood in this pair of works depicting scenes from the American South. With your students, view and compare Edward Hopper’s painting South Carolina Morning (1955) with William Eggleston’s photograph Huntsville, Alabama (1971).

a. Ask students to spend some time looking at the figures in these two works. Study the poses, facial expressions, and body language of the man and woman. How would students describe the figures? Why?

b. Compare the setting and composition of each work. What are the similarities and differences? Encourage students to consider color, light, space, perspective, and point of view. Discuss the mood of each work. What details contribute to the mood? If students were to assign a genre to the story implied in each work, which genre would they assign? Why?

c. What do students think just happened in each of these scenes? What might happen next? Ask students to choose one of the characters in these works and write a story about the scene. Encourage students to incorporate details of what they see as well as using their imagination to compose their narrative. Share and discuss students’ stories with the class. What narratives did they create based on their own observation and imagination?

Artist as Experimenter

TRANSFORM A SYMBOL

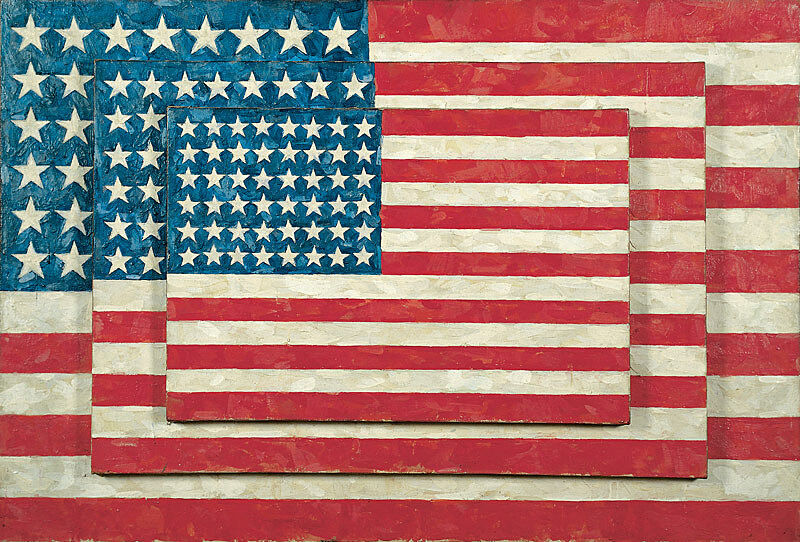

Jasper Johns said that the American flag is something “the mind already knows.” In 1954 when he began making paintings of the flag, he also realized that it was “seen and not looked at, not examined.”

a. View and discuss Jasper Johns’ Three Flags. How is it different from an actual American flag? What does this painting make students notice about the American flag that they may not have paid attention to before?

b.Tell students that this flag has forty-eight stars because it was painted in 1958, before Alaska and Hawaii were admitted into the Union in 1959. Ask students to discuss what was going on in society and politics during the 1950s such as the Korean War, McCarthyism, the space race, the Cold War, television, and the rise of consumer culture.

c. While Johns has shifted emphasis away from its symbolic meaning, the flag is nevertheless a potent symbol. Discuss how the symbol of the flag connects to the time when it was made. How does it resonate with students today? What does it mean to them?

d. In this painting, Johns repeated and stacked the flag image three times. This is one of several images of flags that he made. Ask students to brainstorm an image whose composition and symbolism is meaningful to them. What symbol would they choose to experiment with? Why? Ask your students to find multiple images of that image/symbol, and if possible, in different sizes in order to make a collage using the symbol. They can experiment with shifts in scale, composition, overlapping, and orientation. View and discuss students’ collages. What did they discover about their symbol in the process of making their collage? What message does their collage convey?

Post-Visit Activities

Objectives:

Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition American Legends: From calder to O’Keeffe.

Have students further explore some of the artists’ approaches through discussion and art-making activities.

Make connections with some of the artists’ sources of inspiration.

Artist as Observer

REINVENT AN ARTWORK

Artist as Experimenter

FIND AND DRAW A FRAGMENT

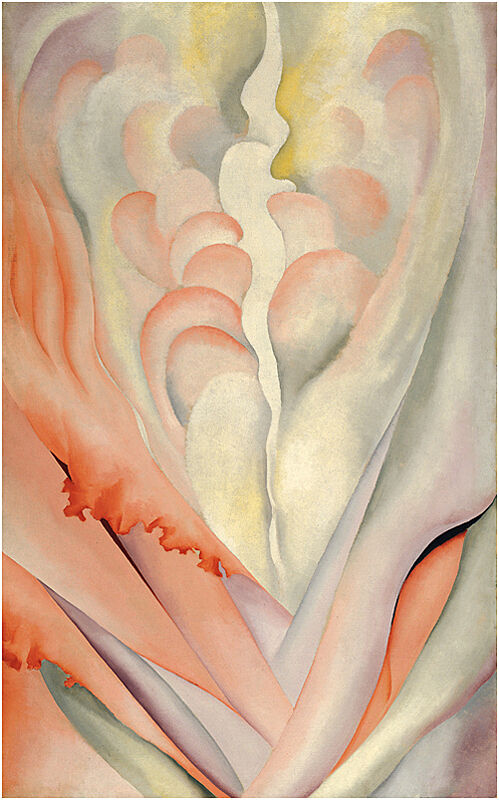

Georgia O’Keeffe and Ellsworth Kelly used imagery derived from the real world, but they used two different approaches to arrive at abstraction. In Flower Abstraction (1924), O’Keeffe focused on the natural world, depicting a close up, cropped view of a flower, while Kelly observed and recorded part of a plant in a contour drawing.

a. How would your students define and/or describe abstract art? View and discuss O’Keeffe’s Flower Abstraction (1924) and Ellsworth Kelly’s Briar (1963). Have students describe what they see in each work. What do they think the artists did to abstract their images?

b. Next look at images of plants and a close up image of a flower similar to O’Keeffe’s (do a google images search for “dahlias close up.”) Compare the paintings and the photographs.

c. Ask students to abstract their own fragment of a natural object. Have them make a viewfinder out of card stock using the template or by tearing a small hole from the center of a sheet of paper. Have students frame part of the object by holding their viewfinder in one hand at arm’s length and look through the center hole with one eye closed, and then draw what they see with their other hand. Share students’ drawings with the class. What kinds of abstractions did they create?

IMAGES & RELATED INFORMATION

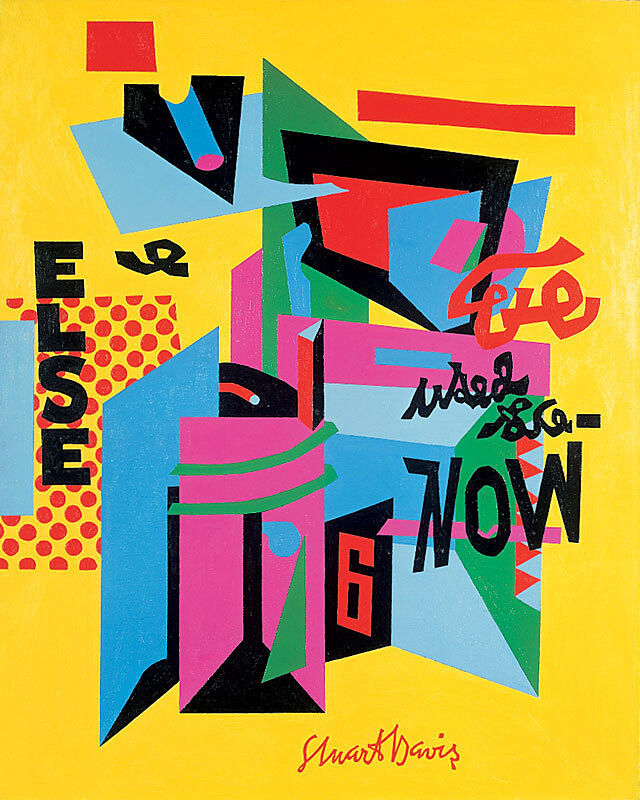

STUART DAVIS

OWH! IN SAN PAÕ, 1951

Just as jazz musicians improvise on extant melodies or incorporate fragments from disparate tunes into new compositions, Davis used earlier compositions as springboards for new works, especially after 1950. Owh! In San Paõ derives its basic configuration from his 1927 painting of a coffee pot—a reprise he playfully acknowledged by imbedding the words “else,” “now,” and “used to be” in the composition. For Davis, these words functioned both as structural elements and as carriers of meaning. Together with the composition’s bold colors and the syncopated rhythms of its interlocking geometric shapes, they contribute to the impression that forms are coming apart and flying across the canvas—an apt correlative to the exhilarating speed and fragmentation of modern life.

About the Artist

STUART DAVIS

1894-1964

Born in Philadelphia, Stuart Davis grew up in an artistic milieu. His mother was a sculptor, and his father was the art director of the Philadelphia Press. When Robert Henri, leader of the Ashcan group of painters and a colleague of Davis’s father, opened an art school in New York in 1909, Davis dropped out of high school to attend. According to Davis, the school was a chaotic, creative center that encouraged students to go out and paint the everyday urban life around them. Davis was a jazz fan, and began painting watercolors of the local jazz dancehalls and bars. In 1913, he encountered what he would call “the greatest single influence I have experienced in my work” when he attended the Armory Show in New York, which introduced American audiences to the avant-garde developments in European art. He was particularly drawn to the work of Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh, and Henri Matisse for their bold use of non-associative color and simplified forms.

During the 1920s, Davis developed a style that combined the fractured vocabulary of Cubism with American vernacular subjects, using everyday objects such as eggbeaters and cigarette boxes as his inspiration. He also painted street scenes of New York and Paris, often rearranging the forms of signs, fire escapes, and skyscrapers into flat planes of color and texture. His distinctive fusion of simplified, abstracted forms with imagery drawn from American popular culture made his work a forerunner of Pop Art. In the late 1930s, Davis’s paintings became even more vibrant than previous works and more closely associated with jazz, which he saw as the musical counterpart of abstract art.

During the Great Depression, Davis took a position in the Works Progress Administration’s mural and graphics division. His assignment included the creation of a mural for the New York World’s Fair called History of Communications. Politically active at that time, Davis joined various organizations designed to protect artists’ cultural freedom and economic security and wrote numerous articles on these topics. Reflecting on his career in 1943, Davis’s autobiographical sketch poked fun at art world labels: “Paris School, abstraction, escapism? Nope, just color-space compositions celebrating the resolution in art of stresses set up by some aspects of the American scene.”

Claude Marks. World Artists 1950-1980: An H. W. Wilson Biographical Dictionary. (New York: H. W. Wilson Company, 1984), 183.

Ibid. 185.

WILLIAM EGGLESTON

HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA, 1971

Huntsville, Alabama is one of forty-eight photographs included in William Eggleston’s Guide, the book that accompanied his landmark exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1976. Casual yet arresting, the image of a businessman in a hotel room—taken on one of Eggleston’s many journeys through the American South—exemplifies not only his command of color (the saturated hues of the citron walls and crimson carpet are brought out through the dye-transfer print process) but also his seemingly intuitive feel for pictorial composition. While the photograph possesses the snapshot aesthetic that is characteristic of his work, Eggleston also dramatizes the scene by framing the man with an opening in the wall. For all of their seeming straightforwardness, however, mood often remains ambivalent or open-ended in Eggleston’s photographs. About the subject in this work, for example, he recalled, “He seems quite lonely. But that’s just the way he seems. He didn’t feel that way. He was having a very nice bourbon. He was in a good mood.”

William Eggleston, interview with Richard Lacayo, “Last Talk with: William Eggleston,” Time Magazine, 11 November 2008. http://lookingaround.blogs.time.com/2008/11/11/last-talk-with-william-eggleston-2/

About the Artist

WILLIAM EGGLESTON

B.1939

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, William Eggleston grew up mostly in Sumner, Mississippi in a prosperous family that encouraged his creative pursuits. His grandfather introduced him to photography at a young age, and when he was around ten years old, Eggleston opened what he called the “Jiffy Print Shop” in his grandparents’ basement, after assembling a printing press inspired by a book he read on Gutenberg. He attended several colleges in the South, including Vanderbilt University in 1957 and the University of Mississippi from 1958-1960, though he never graduated. During his college years, Eggleston developed a keen interest in photography, acquiring a 35mm viewfinder camera.

In the early 1960s, Eggleston married and moved to Memphis, where he has lived ever since. He first worked in black-and-white, but by the end of the decade began photographing primarily in color, imbuing his pictures with deeply saturated, often garish hues and the spontaneous quality of snapshots, often shooting from an unexpected, low or off-center angle, positioning the subject diagonally as well as symmetrically. Early on, Eggleston realized that he needed to find his own subject matter. “What was new back then was shopping centers, and I took pictures of them,” he remarked. During this period and into the 1970s, he photographed the Mississippi Delta of his youth, transforming ordinary subjects into indelible images that bordered on kitsch and eschewed conventional notions of beauty. He also began traveling across the United States with his camera and experimenting with video, utilizing the first portable video cameras that had just come on the market.

In 1976, curator John Szarkowski organized an exhibition of Eggleston’s color photography at the Museum of Modern Art, referring to Eggleston as “the inventor of color photography,” which, until then, had been deemed suitable only for advertising and commercial work. One critic wrote that the pictures were “perfectly boring” and belonged to the world of “snapshot chic;” another labeled it the worst exhibition of the year. But others admired the authenticity and purposeful imperfection of Eggleston’s images and hailed them as representing a new direction in contemporary photography. Eggleston has discouraged over-interpretation of the content of his pictures, preferring to emphasize their purely visual qualities. Internationally acclaimed and widely traveled, Eggleston has spent the past several decades photographing all around the world, continuing to convey his intuitive responses to local cultural phenomena and the eccentric details of everyday life.

EDWARD HOPPER

SOUTH CAROLINA MORNING, 195

From April 1 to May 11, 1929, Edward Hopper and his wife, Josephine Nivison Hopper, visited Charleston, South Carolina. During their trip to the surrounding countryside, the Hoppers encountered a woman who stood in front of her cabin but retreated indoors when her husband came home. Many years later, Hopper revisited this chance meeting in South Carolina Morning, the only painting in his oeuvre that depicts an African American woman. Here, she stands poised on the steps of a building surrounded by an austere slab of sidewalk, which is the only transitional element between the structure and a vast plain of sea grass that extends to the horizon. The inhospitality of the landscape is echoed by the protagonist’s defensively crossed arms and the building’s closed shutters. At the same time, however, the woman’s black heels, diaphanous red dress, and matching lipstick convey a sense of glamour and sexual invitation—their incongruity with her barren, rural surroundings infuses the scene with mystery and dramatic tension.

About the Artist

EDWARD HOPPER

1882-1967

One of the most important realists of the twentieth century, Edward Hopper painted intimate scenes of American life in a career that spanned over six decades. From 1900 to 1906, Hopper attended the New York School of Art, where he studied painting with urban realist Robert Henri. Hopper spent three extended sojourns in Paris between 1906 and 1910. While there, he visited avant-garde exhibitions such as the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne, but he was more influenced by the work of Edgar Degas and the Impressionists than the period’s contemporary movements such as Fauvism and Cubism.

By the 1920s, Hopper was rendering these subjects in his characteristically spare and direct manner, emphasizing contrasts between light and shadow and unusual vantage points through the use of windows and doorways. Hopper’s isolated figures, estranged couples, and stark rooms imbue his images with a deep sense of mystery, loneliness, and solitude. Hopper had his first solo exhibition in January 1920 at the Whitney Studio Club in Greenwich Village, a hub for independent artists and the precursor to the modern Whitney Museum. In 1924, a successful New York gallery exhibition enabled him to give up commercial work altogether and concentrate full-time on painting. That same year, Hopper married Josephine Verstille Nivison, a painter who would be the model for almost every female figure he subsequently painted.

Throughout his career, Hopper returned again and again to the same subjects. Cape Cod, where he and Jo spent their summers, inspired paintings of lighthouses, rocky coasts, railroads, and New England houses. In New York, where he lived and worked in the same apartment overlooking Washington Square for more than fifty years, Hopper depicted the everyday sites of the modern city—movie theaters, restaurants, shops, and apartment interiors. Through a poetic, cinematic use of light and architecture, Hopper invested his scenes of ordinary American life with a haunting sense of drama and desolation. While American art in the 1950s and 60s moved away from traditional realism, Hopper had little interest in contemporary movements like Abstract Expressionism or Pop art. “The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form, and design,” he said. “Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.”

Edward Hopper interview, 1959 June 17, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution,

http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/hopper59.htm

JASPER JOHNS

THREE FLAGS, 1958

In 1954, Jasper Johns began painting what would become one of his signature emblems: the American flag. As an iconic image—comparable to the targets, maps, and letters that he also has depicted—Johns realized that the flag was “seen and not looked at, not examined.” The execution and composition of Three Flags elicit close inspection by the viewer. The painting draws attention to the process of its making through Johns’s use of encaustic, a mixture of pigment suspended in warm wax that congeals as each stroke is applied; the resulting accumulation of discrete marks creates a sensuous, almost sculptural surface. The work’s structural arrangement adds to its complexity. The trio of flags—each successively diminished in scale by about twenty-five percent—projects outward, contradicting classical perspective, in which objects appear to recede from the viewer’s vantage point. By shifting the visual emphasis from the flag’s emblematic meaning to the geometric patterns and variegated texture of the picture surface and the canvas structure, Johns explores the boundary between abstraction and representation and the differences between a flag and an image of a flag. As he remarked, this painting allowed him to “go beyond the limits of the flag, and to have different canvas space.”

Maxwell L. Anderson. American Visionaries: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2001, 154.

Joseph Young. “Jasper Johns: An Appraisal,” Art International, v.13, No. 7, September 1969, 51.

About the Artist

JASPER JOHNS

B. 1930

Born in Augusta, Georgia, Jasper Johns grew up in rural South Carolina during the Depression. Primarily a self-taught artist, he began drawing as a child and received some formal art training in 1947 at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. After serving in the army during the Korean War from 1951-53, he settled in New York, where he supported himself doing odd jobs, including designing window displays for department stores, while devoting his spare time to making art. Few of Johns’ earliest works survive, as he decided to destroy virtually all of the art he had made up to this point and begin anew. During these years, he forged close relationships with composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham as well as artist Robert Rauschenberg, with whom he would live and work until 1962.

In 1954, at the height of Abstract Expressionism, Johns began to produce compositions based on numbers, targets, and the American flag—familiar things that he would later describe as “preformed, conventional, depersonalized, factual, exterior elements.” His decision to paint these commonplace items with resolute flatness seemed audacious and brought him immediate critical and commercial success. In 1958, three of the paintings in his first solo show at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art and one of his target paintings appeared on the cover of ArtNEWS magazine. The works heralded a new direction in artmaking, away from Abstract Expressionism and toward what would later become Pop art.

Following this breakthrough, in the late 1950s and 1960s Johns animated his surfaces with more aggressive brushstrokes while also introducing other motifs into his work—words, letters, and maps of the United States. He often attached real objects or plaster casts to the canvases, which in turn inspired the production of bronze sculptures of such quotidian objects as flashlights, light bulbs, and beer cans. During the 1960s, Johns also became deeply engaged with printmaking, which has remained a central part of his creative process.

Beginning in 1974, Johns turned to an abstract hatching motif, employing clusters of parallel lines as a recurring pattern in paintings, drawings, and prints. In the 1980s, he returned to representational imagery and three-dimensional objects, incorporating body casts, faucets, clothing, and ceramic elements into his work. Throughout this period, his art became increasingly personal and self-reflexive, with allusions to art historical figures such as Pablo Picasso, Edvard Munch, and Matthias Grunewald as well as to memories of his early childhood. Following his 1996 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, Johns commenced his Catenary series, which include a string that hangs from the upper right to lower left of his canvases, generating a curve called a “catenary.” Johns currently lives and works in Connecticut and the island of St. Martin, in the French West Indies.

Interview with David Sylvester, recorded for the BBC in June 1965 in Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbooks and Interviews. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996, 113.

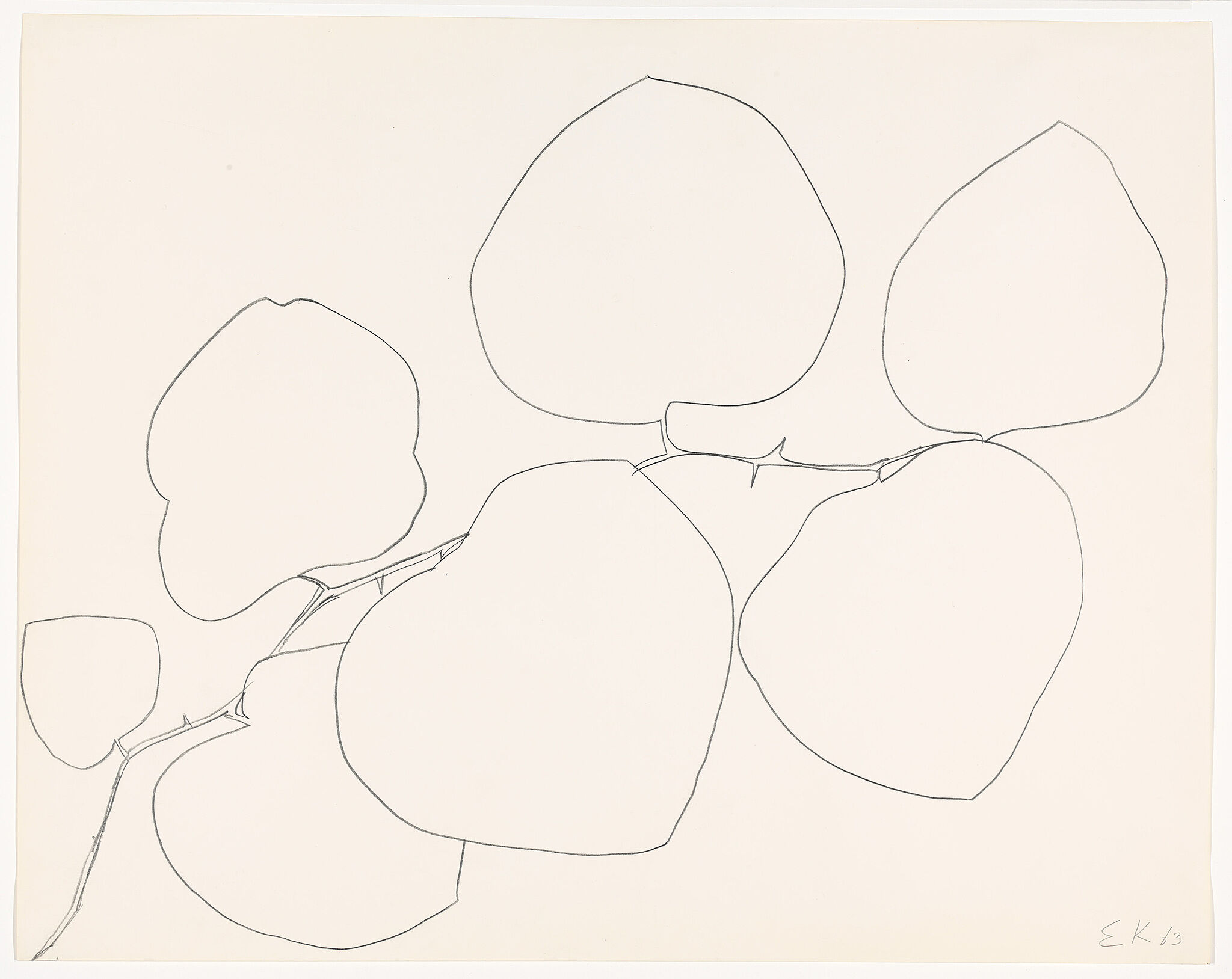

Ellsworth Kelly

BRIAR, 1963

Using a pared down vocabulary and a deeply honed instinct for perceptual nuance, Ellsworth Kelly has explored the experience of seeing and the tensions and balances of edge, shape, line, and color. Although he is best known for his large-scale abstract paintings, Kelly’s images are derived from his observations of the real world. He said: “I never get bored; everything I see is freshly minted.” While living in Paris in the spring of 1949, Kelly made his first contour line drawing of a plant, a practice he has continued to this day. Most of the plant studies depict leaves, stems, and flowers, executed in pencil or pen and centered on the paper. Kelly does not use shading, but relies on line to convey volume, creating a reductive but descriptive image. His economic ordering of shapes and their placement on the page combined with the tension between each line and the form that it describes together yield the fusion of severity and sensuality that characterizes his art in all media. In Briar, assured graphite lines enclose the shapes on white paper, yet the drawing is as much about the negative space among the forms defined by the plant: the play of figure-ground at the heart of the artist’s practice.

Toby Kamps. “Ellsworth Kelly: Red Green Blue,” Conversations with Ellsworth Kelly between November 2001 and February 2002, Ellsworth Kelly: Red Green Blue, Paintings and Studies, 1958-1965, San Diego: Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, 2002, 16.

About the Artist

ELLSWORTH KELLY

B. 1923

Ellsworth Kelly’s meticulously hard-edge paintings and sculptures rarely reveal their referents, cutting ties with the artist’s real-world sources of inspiration. Instead of narrative association and emotional content, they offer only flat, unmodulated color, simple form, and planar frontality. Using canvases of varying shape and dimension, Kelly has investigated figure-ground relationships, chance procedures, and other fundamental elements of painting. His sculptures—wall-mounted reliefs, floor sculptures, and freestanding objects—consist of cutout metal or wood shapes related to those in his paintings.

Raised in New Jersey, Kelly became a passionate birdwatcher as a child, an experience to which he attributes his interest in visual acuity and natural form. In 1948, after serving in the U.S. Army during World War II in a unit that designed camouflage, Kelly enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris on the G.I. Bill. His initial interest in the human figure, inspired by Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee, gave way to abstraction in 1949 as he gained exposure to the work of avant-garde European artists such as Constantin Brancusi and Piet Mondrian. Even as he moved away from figuration, Kelly’s paintings took as their source the architectural and natural details that he observed in his surroundings. In 1950, he met Jean Arp, whose random approach to composition prompted Kelly to incorporate elements of chance into his own work.

Kelly moved to New York in 1954 and launched into what would become his signature style—compositions with large fields of color and crisply contoured, biomorphic and geometric shapes. He also began his customary practice of compiling his drawings, collages, and photographs in sketchbooks that he calls “tablets.” He often returns to these for compositional ideas; as he stated, “drawings have memory; each one has an episode.” Over the years, Kelly has experimented with combining multiple monochromatic panels in a single work, and his palette has ranged from bright, high-key colors to more limited schemes of black and white, or variations of grey. But the reductive, hard-edge style of Kelly’s early abstractions, which helped pave the way for Minimalism’s emergence in the mid-1960s, has remained the salient characteristic of his work throughout his career.

Toby Kamps. “Ellsworth Kelly: Red Green Blue,” Ellsworth Kelly: Red Green Blue, Paintings and Studies, 1958-1965. San Diego: Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, 2002, 16.

ROY LICHTENSTEIN

GIRL IN WINDOW (STUDY FOR WORLD’S FAIR MURAL),

1963

Roy Lichtenstein drew his subject matter from a broad range of sources, including comic books, newspaper ads, and historical works of art. Lichtenstein did not borrow these preexisting images outright, but translated them into his own idiom, “using those symbols to make something else,” as he put it. In 1963, architect Philip Johnson commissioned Lichtenstein to paint a panel for the New York State Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, New York. Girl in Window is a study for his 20-foot mural, which was installed on the outside of Johnson’s circular Theaterama building. The study is executed in flat areas of color and Ben Day dots—a technique that mimics commercial printing and that marked his signature Pop style. Lichtenstein depicted the smiling girl as if she was emerging through an open window from inside the building or breaking through the frame of the picture, an illusion that visually contradicts the two-dimensional surface of the picture plane.

Marla Prather, and Dana A. Miller. An American Legacy, A Gift to New York: Recent Acquisitions from the Board of Trustees. New York: Prestel, 2002, 4.

About the Artist

ROY LICHTENSTEIN

1923-1997

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE

FLOWER ABSTRACTION, 1924

Flower Abstraction is among the earliest of Georgia O’Keeffe’s iconic large-scale flower paintings. O’Keeffe began depicting flowers around 1919, and by the mid-1920s, she started to harness the techniques of close-cropping and magnification she learned from modernist photography to transform her botanical subjects into compositions that oscillate between abstraction and representation. Immediately after she unveiled them in the landmark 1925 exhibition Seven Americans, critics began reading O’Keeffe’s flowers as emblems of female sexuality, even though the artist disagreed with these Freudian interpretations. O’Keeffe explained that she chose the magnified scale to defamiliarize her subjects and thus capture the attention of her viewers: “Paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it—I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

Patterson Sims. Whitney Museum of American Art: selected works from the permanent collection. 2nd ed. Compiled by Kristie Jayne. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1994, 53.

About the Artist

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE

1887-1986

Born on her family’s dairy farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, Georgia O’Keeffe studied at the Art Institute of Chicago (1905-1906) and the Art Students League in New York (1907-1908). After finishing school, she abandoned painting for several years due to family difficulties and her own doubts about her artistic direction, choosing instead to work as a commercial illustrator in Chicago. She subsequently pursued a career as an art teacher, taking courses at the University of Virginia and Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York, where she studied with influential art educator Arthur Wesley Dow and earned a teaching certificate in 1916. Between 1915 and 1917, during teaching stints at colleges in South Carolina and Texas, O’Keeffe created a series of radically abstract charcoal drawings and watercolors, many of which contained a spiraling, organic form. These works brought her to the attention of photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who exhibited them at his 291 gallery in 1916, launching her career as one of America’s foremost modernists. As a member of Stieglitz’s stable, O’Keeffe joined the company of Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin; during this period she also began a relationship with Stieglitz, whom she married in 1924.

In 1918, O’Keeffe quit teaching and moved to New York, dividing her time for the next ten years between the city and the family estate in Lake George, New York, belonging to Stieglitz. As she began to paint full-time, O’Keeffe transitioned from watercolor, which was her primary medium while in Texas, to oil painting. Her earliest oils are largely abstract, based on natural forms and the rhythms of music. By the mid-1920s, she was painting her iconic, voluptuous depictions of flowers—magnified and cropped as if by a camera—as well as Manhattan skyscrapers and Lake George landscapes. In 1929, O’Keeffe began to spend her summers painting in New Mexico; she settled there permanently in 1949, three years after Stieglitz’s death. In New Mexico, O’Keeffe found a rich source of subject matter, painting churches, the landscape, and bones that she collected in the desert. In her late work, she returned to the abstract forms of her early charcoals and watercolors, while also expanding her repertoire to include monumental paintings inspired by the architecture of her home in Abiquiu, New Mexico, and the experience of traveling by airplane. By the mid-1970s, O’Keeffe’s failing eyesight forced her to cease painting. She published her autobiography in 1976.

Bibliography and links

Anderson, Maxwell L. et al. American Visionaries: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2001.

Bryant, Jen. Georgia’s Bones. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2005. Ages 4 and up.

Haskell, Barbara (ed.). Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction. (exh. cat.) New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

http://www.moma.org/collection/artist.php?artist_id=1412

Stuart Davis biography and images on the Museum of Modern Art’s website.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hopp/hd_hopp.htm

Edward Hopper on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website.

Jasper Johns Flag painting and information on the Museum of Modern Art’s website.

Works by Ellsworth Kelly and a biography on the Museum of Modern Art’s website.

http://www.lichtensteinfoundation.org/

Roy Lichtenstein Foundation.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/geok/hd_geok.htm

Georgia O’Keeffe on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website.

The Whitney’s collection and resources for K-12 teachers.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; Heather Maxson, Manager of School, Youth, and Family Programs; and Ai Wee Seow, Coordinator of School and Educator Programs.

Ongoing support for the permanent collection and major support for American Legends is provided by Bank of America.

Support for this exhibition is provided by Susan R. Malloy, The Gage Fund, and Lynn G. Straus.

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s School and Educator Programs are made possible by endowments from the William Randolph Hearst Foundation and the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Fund.

Additional support is provided by Con Edison, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools endowed by the Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.