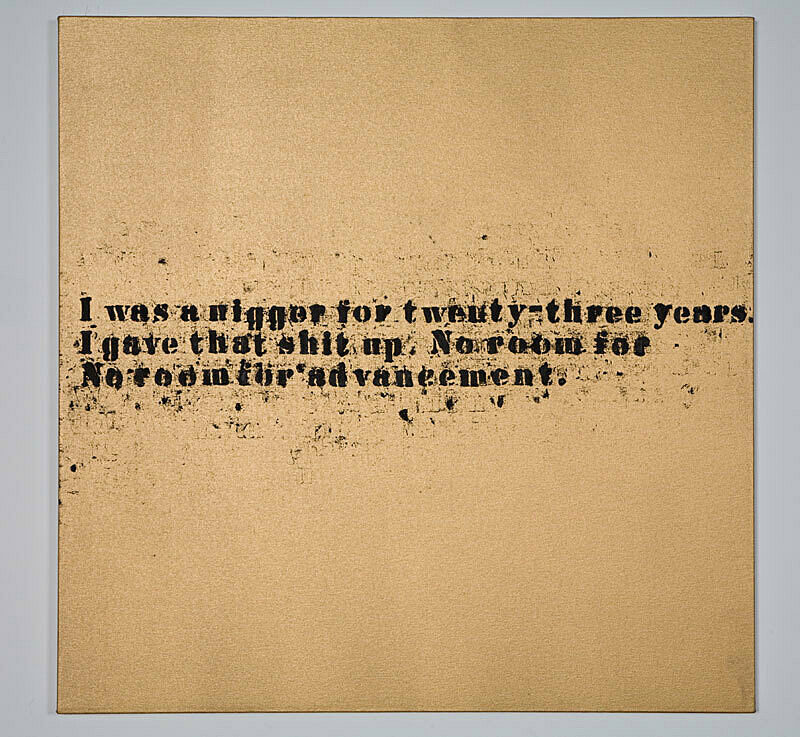

On View: No Room (Gold) #42

Mar 29, 2013

The Blues for Smoke exhibition explores a wide range of contemporary art through the lens of the blues and blues aesthetics, introducing the blues, not just as a style of music, but as a more pervasive sensibility that informs the work of visual artists as well. The exhibition traces the influence of the blues among artists varying in age, race, and gender, and working in such diverse media that the show surprised and demanded reflection at every corner.

Though bright colors and unconventional materials enticed me as I walked through the exhibition, I was drawn to a group of three paintings from Glenn Ligon’s No Room (Gold) series. The series is comprised of thirty-six canvases which all display a single quote by stand-up comedian Richard Pryor (1940-2005), taken from a 1971 concert video Live & Smokin’. The quote reads:

I was a nigger for twenty-three years.

I gave that shit up. No room for

No room for advancement.

Ligon stenciled the quote in bold black lettering on a gold background in the center of a square canvas. As I looked at the quote on each of the three paintings, I realized the text layout forced me to read the line just as Pryor may have delivered it on stage, with the words “no room for” repeated twice and separated by a line break—the visualization of a stutter and correcting pause by Pryor.

To compose his text paintings, Ligon often uses stencils. As the stencils are used and reused, the paint congeals on the edges, making the text increasingly illegible. While the No Room (Gold) paintings display a single quote, there are subtle variations among the canvases. I peered closely at each work to examine these nuances. Each letter is stenciled uniquely depending on how much paint was applied, and the remnants and lingering outlines left by letters that have been painted over are slightly different on each of the paintings on view. Looking at the marks made by the stenciled letters I found myself caught between the visual and the textual, at once exploring the letters as abstract shapes and reading the words to decipher their meaning.

I found that Pryor’s provocative and poignant words created a dramatic contrast with the seductive gold background. The longer I looked the more I noticed distinctions between both the letter forms as well as the words. In the third painting Ligon changed Pryor’s line by substituting the word negro for nigger. His interference in the repetition of Pryor’s quote seem to mimic the subtle formal alterations in the letterforms and marks on the canvas. What strikes me about these works in the context of Blues for Smoke is their apparent process, repetition, and improvisation that, like the blues, represents lasting qualities—an ability to confront and challenge, embrace mistakes, endure, and overcome.

By Brittni Zotos, Interpretation Intern