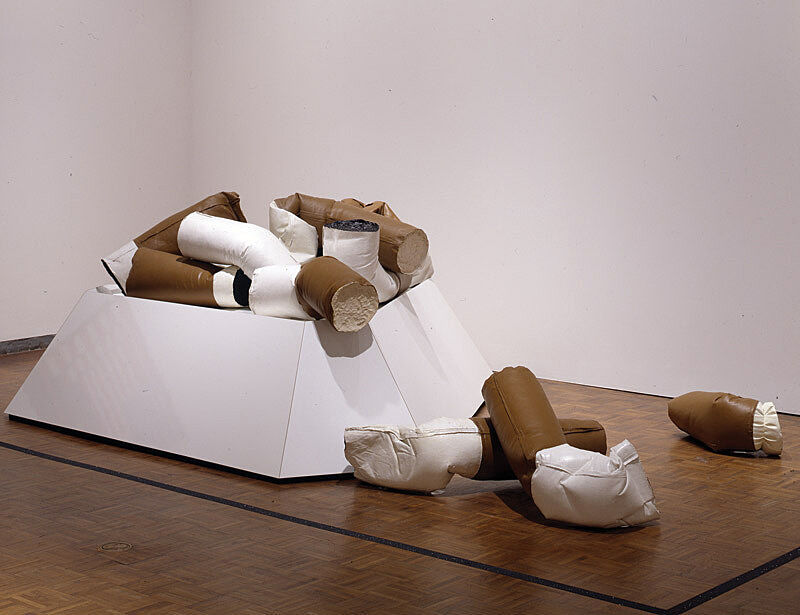

On View: Claes Oldenburg, Giant Fagends (1967)

Dec 14, 2012

While many iconic works of Pop art employ bright colors and playful themes, the Whitney’s collection works on view in the Sinister Pop exhibition explore the movement’s darker edges. Walking through galleries of painting, prints, sculpture, and photography, I felt that the exhibition did an excellent job of capturing this grim underbelly of modern commercial culture. The work that perhaps best articulated the sense of this for me was Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Fagends (1967).

Giant Fagends consists of oversized, urethane-foam cigarette butts crumpled-up on top of one another in a white, polygonal ashtray. They look like cigarette throw pillows made out of synthetic leather. Whatever negative, non-glamorous associations one has about cigarettes—carcinogenic smoke, grubby fingers, stained teeth, and so on—come to the fore here. It literally puts a bad taste in one’s mouth. Oldenburg accomplishes this effect through making an everyday object larger than life. By altering the scale, the viewer is put in a position to consider the cigarettes in ways that extend beyond their functional use. Additionally, he transforms their surface—not into something hard and timeless like marble or bronze—but rather into something soft and squishy.

These were strategies employed by the artist in his many “soft sculpture” works, beginning in 1962. The soft sculptures were a breakthrough in American art because they pointedly embraced low subjects of the modern world such as cigarettes, light switches, ice bags, hamburgers, telephones, and toilets. But through Oldenburg’s seemingly simple gesture, they allowed the viewer to see these everyday objects afresh, as if they’d never really looked at them before. Thus, despite the whimsical qualities of a work like Giant Fagends, Oldenburg accomplishes a significant artistic goal—to represent the world as the world really is. The irony is that Oldenburg did so by distorting the appearance of the cigarettes, making them at once both monstrous and uncannily familiar.

By Gene McHugh, Interpretation Fellow