Looking Back At Black Male

Jan 20, 2015

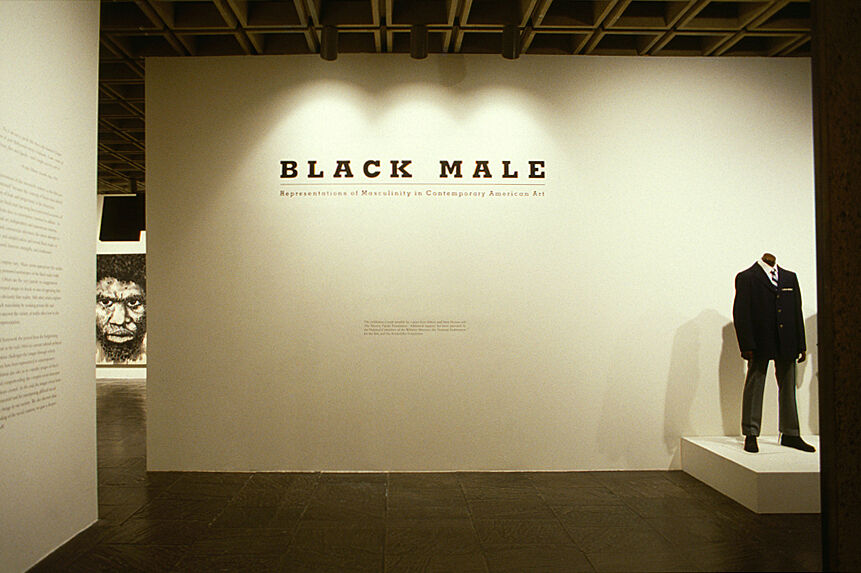

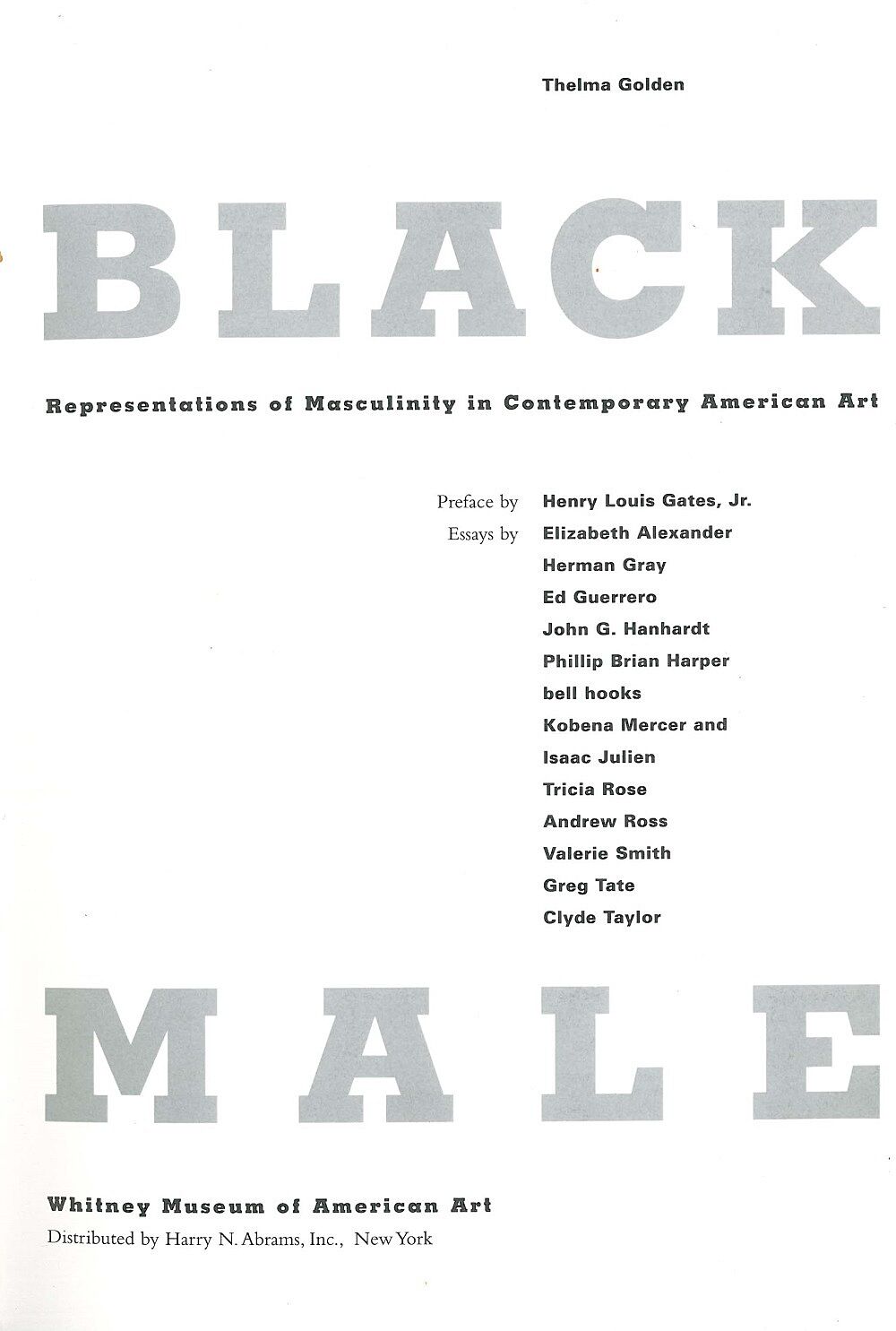

On December 12, 2014, the Education department presented Looking Back at Black Male, a public program to mark the twentieth anniversary of the exhibition Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art, (November 10, 1994-March 5, 1995). Curated by Thelma Golden, now the Director and Chief Curator at the Studio Museum of Harlem, Black Male investigated the complex aesthetics and politics at work in representations of African American men in the post-Civil Rights era. Looking Back at Black Male brought together exhibition curator Golden, Hilton Als, a writer who edited the exhibition catalogue, and Huey Copeland, art historian and critic, to discuss the exhibition and its afterlives.

The program considered Black Male’s significance for cultural debates twenty years ago as well as how it has inspired artists and curators working in its wake. At the beginning of the conversation, Copeland remarked, “As the nationwide protests of the unpunished murders of two unarmed black men, Michael Brown and Eric Garner have again brought into vivid focus, the ’black male’ is a perennial site of fear and projection, policing and pathology, contestation and coalition.” He also stated that the exhibition was not about offering a mirror or image of black masculinity, but providing a context to comprehend how a black male might be produced visually, and the many ways that one might work through that visual production. Referring to the Black Male catalogue as a landmark anthology that has continually sparked many conversations, and a five-part film program organized by John Hanhardt, the Whitney’s former film and video curator, Copeland asked Golden and Als to talk about the ways in which they created a multi-pronged curatorial and cultural approach to the exhibition.

Golden explained that in order to address the complexities of black masculinity, the exhibition demanded many voices and perspectives. There was no previous model for understanding the complicated manifestations and nuances of representations of black men, and she described her feeling that in order to make this exhibition, it was as if a new language had to be invented. Both Golden and Als underscored the importance of the multiple exhibition components to create a broader context for considering the ideas and themes in the works themselves and to engage a wide audience that Golden was hoping would visit the show. Among these components was a context room (located within the exhibition) that displayed a thematic timeline created by cultural historian Maurice Berger, and a series of public programs organized by Connie Wolf, former director of the Whitney’s Education department.

The context room featured an introductory panel and ten large-scale wall texts that, in Berger’s words, were intended to “narrate very selective moments from this complex history of oppression, struggle, survival, and triumph; it is meant as an adjunct to the Black Male exhibition, as a space of learning and contemplation, as a means of contextualizing some of the issues explored in the exhibition.” Themes included Community and Leadership, Civil Rights, Business and Employment, Television and the Media, and Gender and Sexuality. The Business and Employment text panel provided historical information such as: “1971, The U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics reports that African Americans lag far behind whites in economic prosperity, earning three-fifths of the average white income.”

Public programs related to the exhibition included an extensive film program as well as discussions of the event of the show itself. One of these programs was a conversation between cultural historian and Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and philosopher and activist Cornel West. At the beginning of the conversation, Gates asked if the art-viewing public can “move beyond all the polemics about so called positive and negative imagery.” During their conversation about, West mused, “Did [the exhibition] shake you, did it unsettle you, did it in some sense unstiffen your presuppositions as to who and what you are in relation to these black bodies?” Gates emphasized that the importance of discussing the questions posed by the artworks was not only imperative to the exhibition as a whole, but also challenged the viewer to probe his or her understanding of black masculinity.

In her discussion of the exhibition Black Male, Golden emphasized that its accompanying programs were intended to frame the show in dialogue with ideas far beyond the Museum’s walls. Collectively the programs encouraged broader conversations about the exhibition and related cultural issues as a whole. As the exhibition’s introductory wall panel read: ”. . . in the end, the images reveal how the study of art is an essential tool for interpreting difficult social issues and promoting change in our society. We also discover that through an understanding of the social context, we gain a deeper appreciation of art itself.”

By Lauren Cesiro, Public Programs Intern