Walter Annenberg Annual Lecture: Claes Oldenburg

Dec 12, 2011

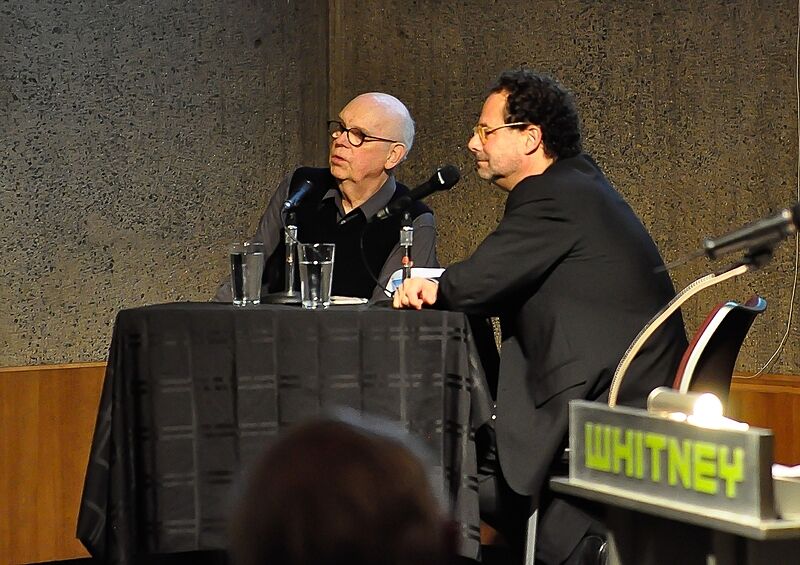

On November 1, 2011, at the seventh Walter Annenberg Annual Lecture, the Whitney honored Claes Oldenburg for his achievements and contributions to the field of American art and culture. In his public conversation with Museum Director Adam Weinberg, Oldenburg reflected on his career, revealing a sensibility that—much like his monumental sculptures—combines humor and earnestness.

Oldenburg offered fascinating stories about his own development as an artist, beginning with his days as a graduate student at the Art Institute of Chicago. He explained that, after “copying” the masters from Pablo Picasso to Willem de Kooning, he felt ready to move to New York and create his own art work based “on intuition” rather than imitation.

In his studio on the Lower East Side, Oldenburg found inspiration in the stores, objects, and consumer goods that surrounded him. He created one of his first major installations, The Store, by sculpting everyday objects and installing them in his studio as if for sale. He explained that he sought to “convert [his] studio into a situation that fit into the surroundings.” This consideration of place turned out to be the driving force behind much of Oldenburg’s career, from his performance pieces, to soft vinyl sculpture and large-scale, public projects.

Though Oldenburg admitted that some of his proposals for Colossal Monuments were “rather aggressive,” he was sensitive—sometimes even pragmatic—about the proposal’s location. In one drawing, for instance, he re-imagined New York’s Pan-Am building (now the Met Life Building) as a gigantic Good Humor Bar, but made sure to design a large ‘bite’ in the structure that would form a tunnel for Park Avenue traffic!

Oldenburg conceded that he spends the most time on, and is best known for, his large-scale sculptures, but noted that drawing, for him, “is the essence of art….if you can make a drawing, the rest can all come along, but you’ve got to have that form, you’ve got to have that structure.”

In addition to drawing, Oldenburg credited his late wife and creative partner, Coosje van Bruggen as pivotal in creating some of their most iconic large-scale works. “She would come in with something very important which changed the form,” he said, remembering how she had suggested they turn the sculpture of a gigantic flashlight, which Claes had intended to shine upwards “like everything else in Vegas,” towards the ground, so that it would be more subtle, muted, and visually interesting in a place full of lights. Oldenburg also recalled how van Bruggen—literally—put the cherry on top of their famous Spoonbridge and Cherry at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Frustrated by the balance of the sculpture, Oldenburg had worked tirelessly to perfect the shape of the utensil. He recalled how van Bruggen immediately determined that the problem was not the spoon’s form, but the fact that “it had nothing in it.”

As the program came to a close, he noted that though his sculpture is often lauded for its humor, it also holds a certain amount of sadness. Indeed, Oldenburg’s work, which combines the prosaic with the extraordinary, is, as he puts it, “a picture of life.”

By Emily Arensman, Coordinator of Public Programs