Conservation Highlights

Carol Mancusi-Ungaro and Yve-Alain Bois on Art Conservation

October 6, 2016: Carol Mancusi-Ungaro presents a lecture entitled “The Falsification of Time” that positions complex issues associated with replication and 3D printing in the historical context of art conservation. Yve-Alain Bois, Professor of Art History at the Institute for Advanced Study, joins Mancusi-Ungaro in conversation after the lecture.

Conserving calder's Circus

Whitney conservators Carol Mancusi-Ungaro and Eleonora Nagy, archivist Anita Duquette, and art historian Joan Simon describe the process of restoring one of the most beloved works in the Whitney’s collection, calder’s Circus.

Andy Warhol's Ethel Scull 36 Times

Whitney associate conservator Matthew Skopek and conservation department intern Sara Kornhauser prepare Ethel Scull 36 Times for the exhibition Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again.

While the work looks like one giant canvas, it is actually 36 individual smaller ones that need to be carefully mounted together. Previously, the canvases had been attached to four cleats, one for each row. However, most of the canvases are not quite a perfect square, so the resulting rows weren't perfectly straight. Installing the work resulted in a bit of a dance, requiring the removal and re-hanging of the rows multiple times to get them to fit. For this project, all 36 of the portraits were removed from their cleats and mounted on a unified strainer. This final group mounting allows for quicker installation, which reduces handling and is safer for the artwork.

Arshile Gorky

These two paintings by Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother, 1926–36 (left), and Painting, 1936–37 (right), were treated in preparation for inclusion in a retrospective of the artist’s work. Surface grime and discolored varnish had formerly obscured the original colors and altered the variation in gloss and saturation as intended by the artist. Some passages of Painting were structurally unstable and required local consolidation before travel. Freed from temporary disfigurements, the newly restored paintings engender a greater understanding of Gorky’s materials and painting technique.

Claes Oldenburg

Both Whitney staff and artist Claes Oldenburg had long considered Ice Bag–Scale C problematic. Technical problems had plagued the giant mechanized sculpture since shortly after its creation in 1971. In consultation with the Oldenburg, a team of conservators, engineers, and other specialists corrected mistakes that had been made in both its initial fabrication and in later attempts at restoration. The piece now operates as the artist had intended for the first time in decades. This innovative treatment was discussed by The New York Times on May 15, 2009.

Edward Hopper

In 1909 Edward Hopper painted these paintings, Bridge on the Seine (left) and Le Pont Royal (right), while living in Paris. Over time, accumulated dirt and discolored varnish had obscured the paint layers. In addition, the varnish that had been applied was felt to be too glossy and out of keeping with the sensitive tonality of the paintings. Removal of these layers revealed the true colors of the brighter palette that Hopper was developing at this time, and the application of a more sympathetic layer of varnish resulted in a more appropriate surface. The treatment of these Hopper works was done in conjunction with ongoing research within the Whitney’s collection into the artist’s materials and technique.

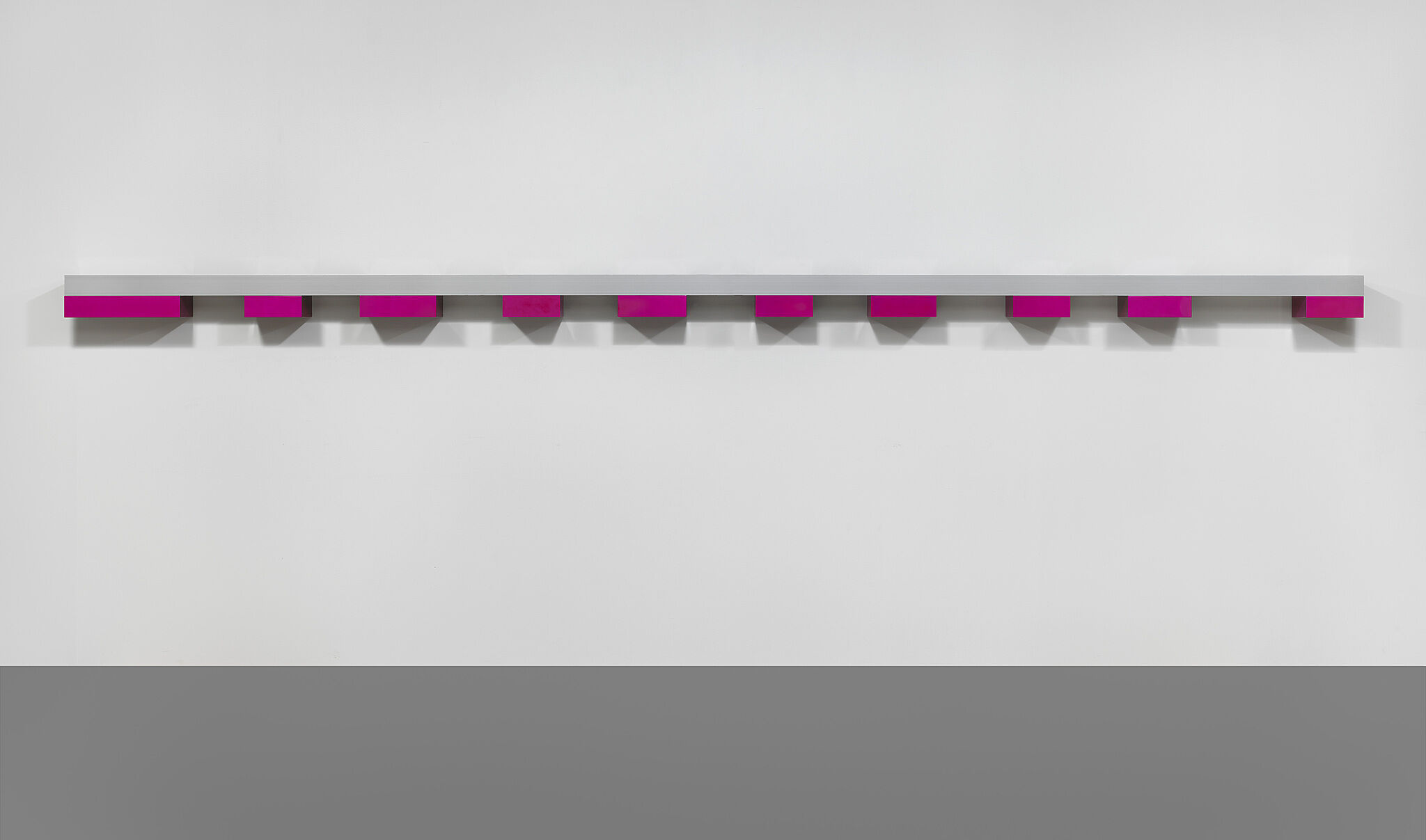

Donald Judd

For his work, Untitled, Donald Judd’s fabricators used a nitrocellulose-based automotive paint that proved to be extremely soft and fragile over time, and the decision was made to repaint. Upon completion of restoration treatment, the artist found that the hard, opaque repainted surface differed significantly from his original and thus no longer represented his work; he then requested that it not be exhibited. When the Conservation Department was established in 2001, this work was revisited and a team of experts was formed, including sculpture conservator Eleanora Nagy, from the Whitney, conservation scientist, Narayan Khandekar of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard University, and a restorer of antique automobiles, Julian Miller, of Sublime Restorations, in Massachusetts. After extensive analysis and testing, the formulation of the original paint was recreated and the work was properly restored.

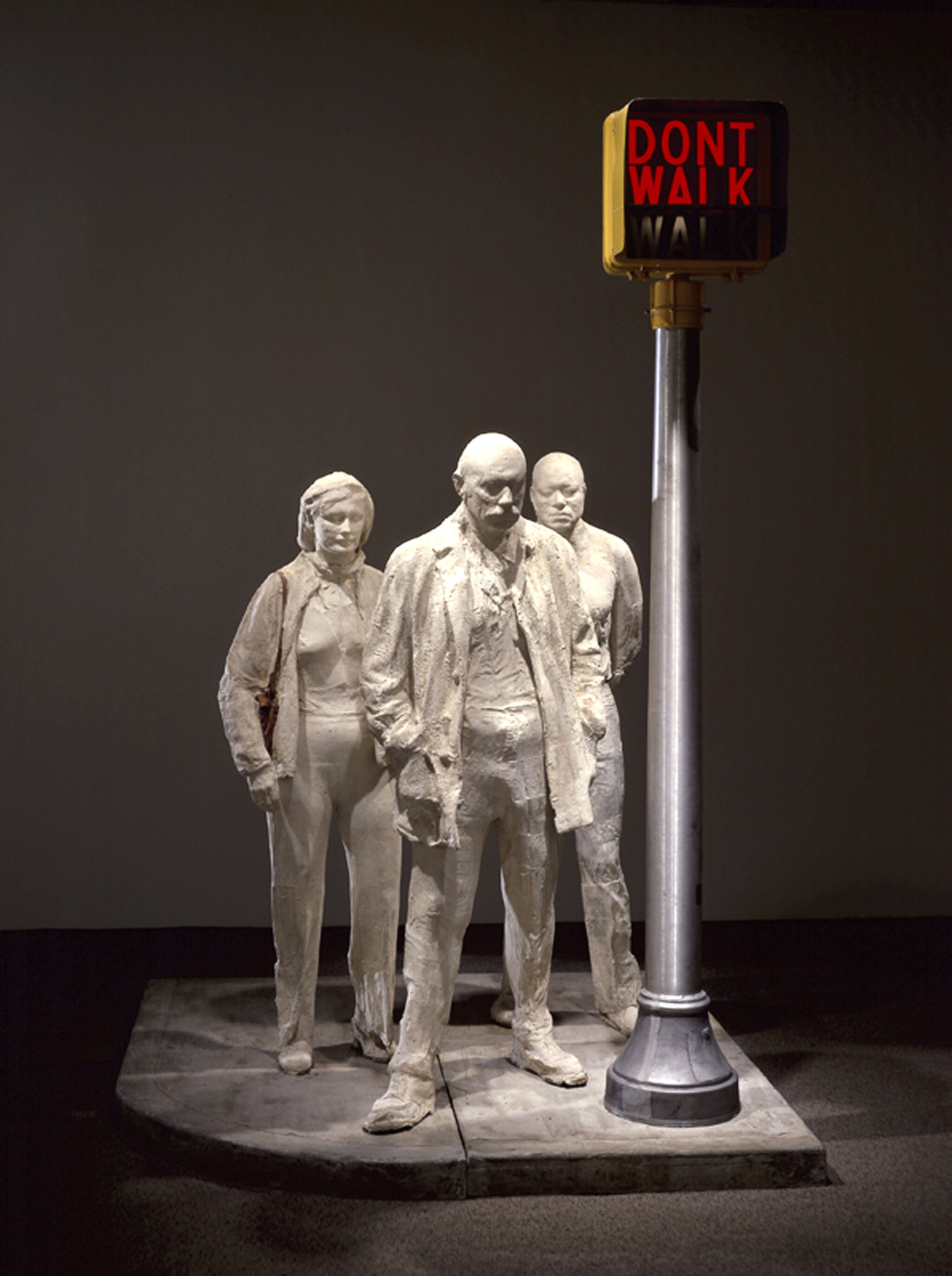

George Segal

All three of the Whitney’s George Segal sculptures—The Bus Station, 1965 (left), Walk, Don’t Walk, 1976 (middle), and Girl in a Doorway, 1965 (right)—have required treatment for a variety of reasons over time. Recently, the figures were stabilized, minor surface grime was reduced, and the proper alignment of the forms within their formats was researched and documented. Despite sundry individual problems, they were treated as a group because a unity of vision and goals during the undertaking positively impacted the result.

Whitney Stories: Carol Mancusi-Ungaro

Associate Director for Conservation and Research Carol Mancusi-Ungaro discusses the importance of the artist’s voice in contemporary art conservation and the development of the Museum's Conservation Center.