Eleanor Antin: Conversations With Stalin

Feb 11, 2013

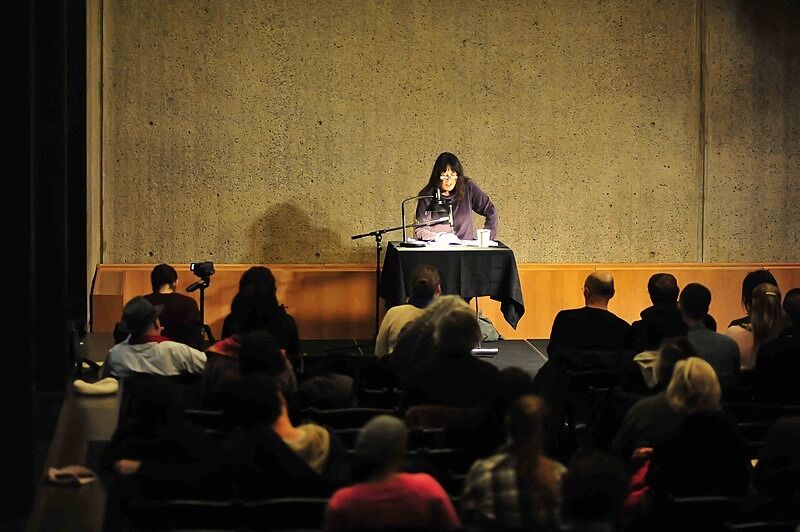

On Friday, February 1, artist Eleanor Antin took center stage in the Whitney’s Lower Gallery to read the final four chapters from her coming-of-age memoir, Conversations With Stalin. This was the final event in a four-part series of readings conducted across New York City—the previous three took place at The Jewish Museum, Ronald Feldman Gallery, and the Brooklyn Museum. Known for employing a variety of mediums spanning photography, video, film, performance, and installation, Antin has often delved into history as a means to explore the present. In Conversations with Stalin, she excavates several layers of personal and political histories to better understand her own childhood and life as an artist.

The first half of each chapter in Antin’s book offer humorous and touching anecdotes from her childhood. A chapter entitled “Twitches and Ticks” referred to her anxieties generated in part from her experiences at a private school in New York City. The next chapter, “Frogs,” chronicles stories from summers spent in the Adirondacks. “Cats and Dogs” covers her budding sexuality and its relation to her growing passions for performance and poetry, and the final chapter of the book, “The Dead,” focuses on deaths she experienced in childhood, from that of Franklin D. Roosevelt to a neighbor’s daughter.

The second half of each chapter responds with poetic and serious conversations between a young Antin and an imagined Joseph Stalin, the former leader of the Soviet Union. In these fictional conversations, Antin seeks solace for the things she can’t understand (such as intelligence, compassion, sexuality, and death)—conundrums which Stalin’s guidance, unfailingly (mis)informed by his Communist politics, only obfuscate further. Antin’s recounting of these stories can be seen as an attempt to reconcile her upraising in what she recounts as an oftentimes confounding socialist and bohemian household.

The combination of light humor and heavy questioning is important to Antin’s work, as she explained: “I always tend to see the funny side of things—that’s the richest experience, when the laughter and the tears are together.” So is the use of historical characters such as Stalin. Antin said: “One of my major passions has always been narrative and I’ve always felt that narrative is as much of a human need as breathing. We're constantly explaining ourselves and communicating in terms of putting material together that in some way has aspects of story.”

Finally, her choice to read the book in its entirety to live audiences casts one more layer of narrative, transforming the more private form of reading and writing into a public one. “I want it to be more intimate than just a book read alone.” Antin said during the final portion of the reading, “That’s the first time I’ve ever read that part to an audience. Now that’s it’s over, it’s made me closer. I know things about the book I didn’t know before.”

By Christopher Reade, Interpretation Intern