99 Objects: Nick Mauss on Sun by Florine Stettheimer

Sep 8, 2015

On July 10, artist Nick Mauss addressed Sun, 1931 by Florine Stettheimer as a part of the 99 Objects public program series. Mauss explores the intersections among different media, and his engagement with Stettheimer’s work integrates painting, poetry, and music.

He explained that Sun features a colorful, oversized bouquet of flowers set in a sunlit scene, but it is not a traditional still life: “This painting is a portrait of a bouquet; it is almost like an actor in this landscape.” The flowers burst toward the viewer, dominating the composition. “There are many bouquet paintings [of Stettheimer’s] where the flowers take on something monumental, or even sort of monstrous,” Mauss explained. “They say something about singularity . . .about clashes, harmonies, extravagances, eccentricities, even about shyness. There’s this way in which the bouquet takes over the painting and then hides a lot of what’s going on in its background.”

Mauss remarked that many of Stettheimer’s works have a cryptic quality: the painting includes several bits of text, most of which are encoded or obscured. The date of the painting is visible near the center of the bouquet, and the artist’s name, “Florine S” flows into the serpentine ribbon tied around the bouquet. Several letters appear behind the flowers, but they are mostly unreadable, and parts of letters seem to be missing.

According to Mauss, this unique visual language that Stettheimer employs has allowed her paintings to become an interpretive filter through which viewers can explore other artists’ work, as well as the broader time period in which Stettheimer was working. He explained, “One of the great gifts of Stettheimer, I feel… [is that her work] opens up all of these social and artistic circles, as well as the forms and rituals of their sociability. They can be read in a way as very lively documents that also. . .skid into fantasy and perverse caricature of a very specific time and place.”

Similarly to Stettheimer, Mauss’s work can also transport viewers to another time and place. His installation for the 2012 Whitney Biennial, which featured a reconstruction of an antechamber from a mid-twentieth century cosmetics company and a variety of objects from the Whitney’s collection, initiated, as the Whitney’s website states, “a spatial, temporal, and psychological shift for viewers.” By hanging familiar works from the Museum’s collection in this unusual venue, Mauss reexamined art historical narratives and prompted visitors to make new connections.

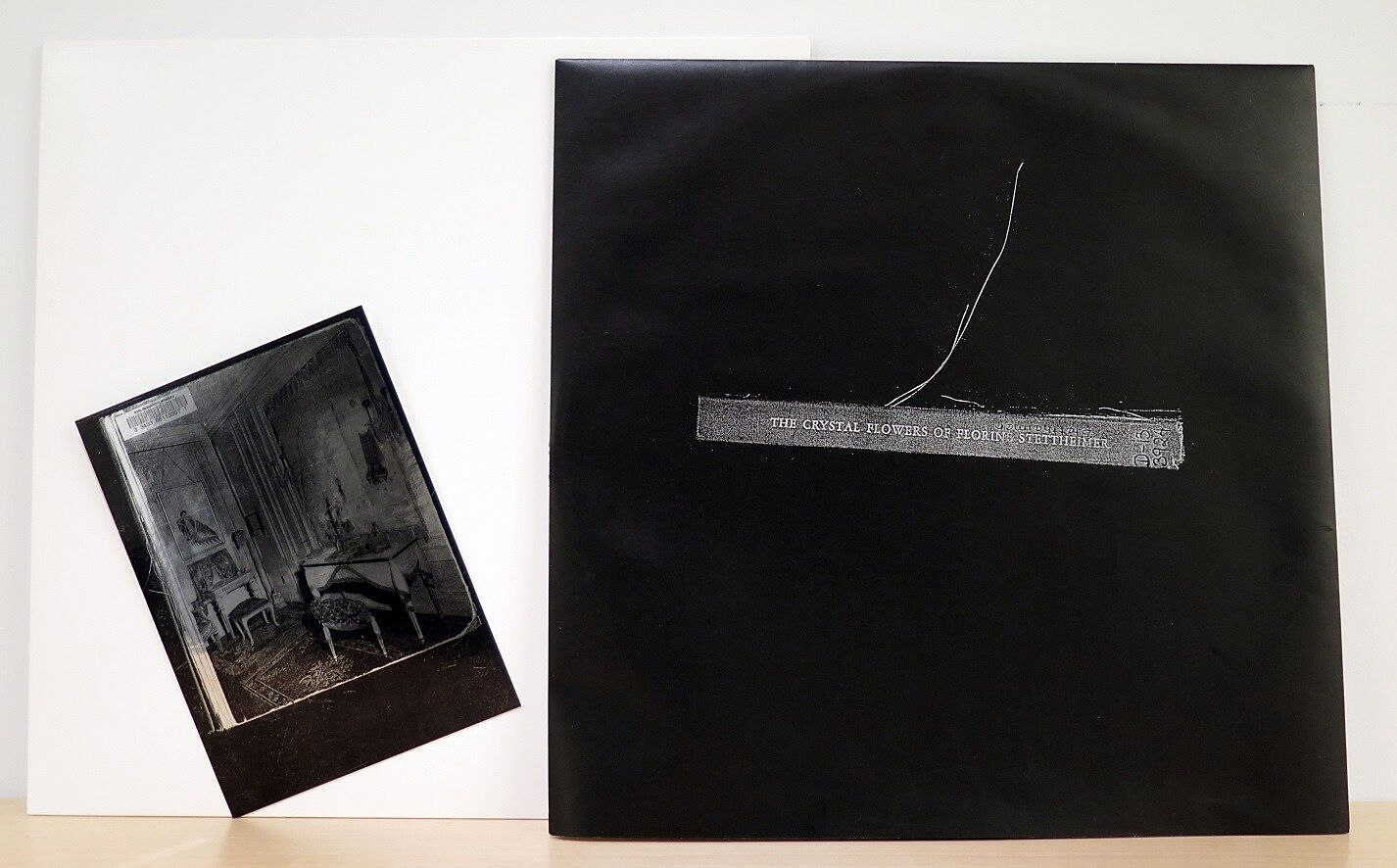

During Mauss’s research on Stettheimer, he came across a collection of her poems, some of which were like diary entries, and also gifts intended for friends and artists. In line with his multidisciplinary practice, Mauss photocopied many of the poems and sent them out to writers, musicians, and artists, asking them to interpret the writings in any way they chose. “What I received in return — there was a huge range, from sober readings to pop songs, to very aggressive mash-ups of the texts, or interwoven texts chosen by various contributors,” he explained. The compilation of newly rediscovered and reinterpreted poems was, in 2012, made into a record titled Crystal Flowers, segments of which Mauss played for the audience. “The act of republishing the poems in this way was also about a distance,” he reflected. “As much as I look at Stettheimer’s work and find out more about it, this process was also very much about not being able to go there, return there, as much as it was also about interpreting, and the possibility of taking this work up and doing something new with it.”

Learn more about upcoming Public Programs here

By Zoe Dobuler, Interpretation Intern