Conserving Mahoning

Oct 23, 2014

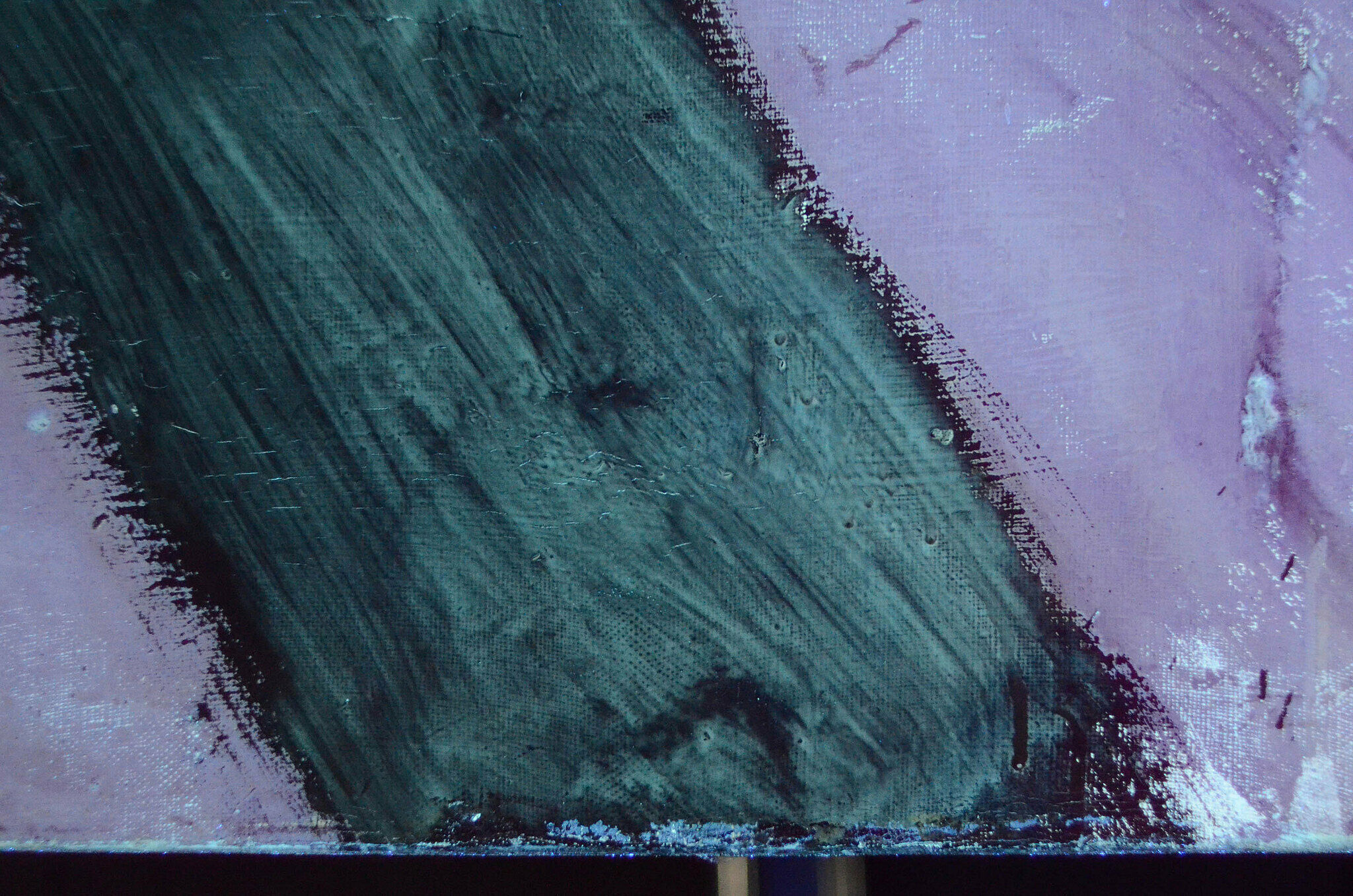

Ever since Whitney Museum conservator Matthew Skopek saw Franz Kline’s Mahoning (1956) as part of a permanent collection exhibition seven years ago, he wanted to restore it. The black-and-white work originally contained a remarkable amount of variation in saturation and tone, but as Mahoning aged, its vibrancy had dulled, and subtle distinctions in color had become uniform. Fifty years after the painting was created, Skopek explains, “Every single black was just the same gloss, the same saturation.” The opportunity to treat the painting arose in 2013 as part of an effort to prepare Whitney permanent collection works for the Museum’s new building, where an unprecedented number of pieces will be on display.

When the treatment process began, Skopek’s aim was to bring the painting back to its original documented state, cleaning it and removing a layer of varnish that had been applied during an earlier conservation effort in 1963. But as he started removing the varnish, he uncovered something unexpected. “I thought that I was going to go back to a certain place that resembled a 1957 photo [taken when the Whitney acquired the work],” Skopek said. “I found something else.” A different varnish had been locally applied to the painting’s broad black sections, and small dabs of brownish-black paint had been roughly affixed with a palette knife. Both the paint spots and the varnish contained the same resin, suggesting that the two modifications had taken place at the same time and were carried out by the same person—the artist.

Skopek speculates that when Kline saw his painting at a 1960 exhibition, there may have been nicks and dings in the paint, and the black color had likely lost some of its saturation—a natural result of the paint continuing to dry in the years after it was painted. Kline had initially sought to create a rich surface, using thinned oil paint and then adding varnish to increase its gloss and depth. Just a few years after making Mahoning, he could see it aging. The artist’s intervention is a surprising revelation, countering his documented claim that he would not mind if his paintings’ materials discolored with age: “The whites, of course, turned yellow, and many people call your attention to that, you know," Kline had said. "They want white to stay white for ever. It doesn’t bother me whether it does or not. It’s still white compared to the black.”* Skopek’s discovery demonstrated that Kline’s engagement with his paintings and materials was deeper than previously known, and changed the course of the conservation treatment; the focus shifted from restoring the painting’s 1957 state to recreating areas where the artist’s later revisions had worn away.

Beyond protecting and preserving the work, this conservation treatment contributed to our knowledge of Kline and his process. The case highlights an element of surprise and spontaneity in a field more commonly associated with its academic rigor. While Skopek’s research on the treatment was extensive (including site visits to other institutions and the examination of receipts and files kept by Kline’s partner, Elizabeth Zogbaum), careful study did not provide all the answers. As Skopek observes, “Any time we clean a painting we’re taking it back to a state closer to what the artist intended, and that can be really rewarding. By restoring it you affect the viewer’s experience and hopefully allow the artist’s voice to speak more clearly. If at the same time you come across something unexpected, then that can be even more of a thrill.” In the end, the work tells its own story.

*David Sylvester, Interviews with American Artists. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. p.61