The Artist Dreams: A Conversation with Hadi Falapishi

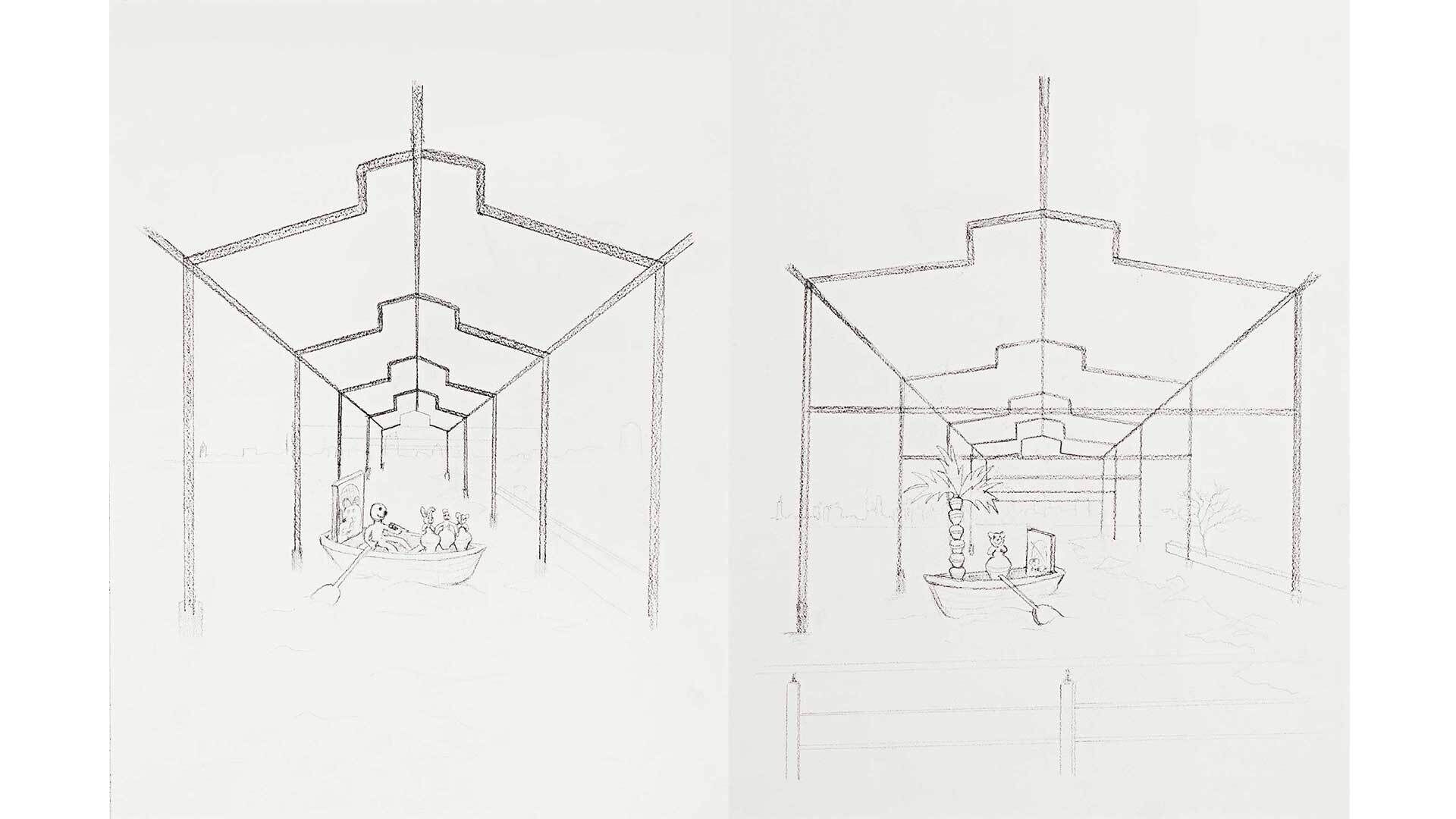

Before Hadi Falapishi was asked to create a site-specific work for the Whitney, he had already been dreaming about the Museum. A series of drawings in his sketchbook depicted a boat, loaded with his sculptural and photographic artworks, floating through the empty armature of David Hammons’s Day’s End (2014–21)—a permanent public art installation located in Hudson River Park directly across from the Whitney. Upon completion of Day’s End in 2021, he regularly biked to the site in order to capture the work in the changing light and mercurial atmosphere. His visits were prescient: “The more I visited, the more I would see that I could fit in this structure. I thought that this could be my museum.” Falapishi has transformed that fantasy and his sketches into a billboard for the Museum’s public art series. On the debut of Almost There (2022) this spring, he shared insights about the image, his process, and the place of the artist in society.

—Lauren Young, Senior Curatorial Assistant

Lauren Young: Could you describe the scene of Almost There and what you were thinking when you conceived it?

Hadi Falapishi: The billboard shows a human carrying a boat on their back, with a cat, a dog, and a mouse on top of the boat. When you look at the image, although it’s very basic and cartoonish looking, it seems like the human is under the water, carrying the boat. The three animals are pointing to an island, with a sun behind some palm trees. And then there is a frame of stuffed animals around it, which is a completely different story.

I wanted this image to be different than what I have previously done. If someone knows my work, they know it usually pictures an interior. It’s a setting of a house, with the same four characters. It’s a domestic scene and what goes on inside. But I did not want to do that with the billboard. I wanted it to be in relation to the land, to the museum, to the placement of the billboard, and to the Hudson River, but also in relation to myself—as an immigrant, where I come from.

Everything I’m describing is what I’m seeing now. When I started making the work, I wanted it to be a version of myself—for it to be a self-portrait. But I also hope that it’s bigger than that. Maybe this is the first human who arrived here; or it might be the last person on our planet, who is perhaps even leaving and going to a new world. Opening up the work as much as I can; that’s part of it. So as personal as it is to me, I hope there’s also a broader understanding and philosophy.

LY: That is one of the greatest aspects of your work—everyone can come to it and see a story, or even multiple stories. It has that potential. The human under the boat can be seen as menacing, like they’re sneakily under the boat. But they could also be carrying or maneuvering the boat, which could be helpful. The scene is very ambiguous. Even the relationship between the different animals is unclear. The animals all got in the boat together, so they must be a group of some kind. But the person—maybe they’re saving them, maybe they’re not.

HF: Absolutely. It has to have that quality. Why is the human hiding under this cheerful boat? It’s not just the boat coming to the land, other things are coming with it too. I think it’s open to different readings. I hope it’ll function with the public similarly.

A lot of my work represents a kind of familial structure and all that comes with it, including all the politics. But the family is also a microcosm of our society. I’m so happy with how this image represents a lot of what we are living today—in our little art world and in New York. And more broadly, issues of immigration, issues of getting to someplace, issues of not knowing the outcome, not knowing what’s ahead of us—and still moving forward.

That circles back to the production of the work. I don’t really know what the result will be until it arrives, until it’s seen by the public. At its best, the work reproduces that quality. This boat seems very happy, but we don’t know where they’re going or what they will face, until the moment that they have arrived and been received.

LY: All those questions are embedded in the image. Where are these animals and this person coming from? Where are they going? What was the intention or the reason behind it? There’s the unknown of what was in the past, but then there is also the unknown of what is in the future. How are they going to be received and greeted in a new place? It’s a moment of suspended potential and opportunity. But in the image itself, that is never—and will never be—culminated. And so you have this moment of “What if?” or “What happens?”

HF: In the past, I was sometimes criticized for including too much information in my work. But I believe that’s part of the work. I’m trying to put in as much information as it can hold, and then at some point it can’t hold anymore. I’m pleased because we can describe the image and talk about all these things—the work allows it. I don’t think we’re pushing it, extending it, or stretching it. I think the work actually carries all this.

LY: To strike on some of the larger themes, it’s an image that can be understood as being about migration or immigration. It’s also an image about America. You are responding to the setting of New York, a place where historically many immigrants first came to the United States. It gestures at how the US was founded and colonized.

If the billboard is an image of the US, then it can also be viewed in terms of current political events and discourse. The island is a paradise, which could be the idea of America or of democracy. In the image, we haven’t gotten there yet. There’s still this utopia that we haven’t reached; the country has the potential to be a utopia, but it’s a question of whether it will be achieved. So while the scene may appear happy, there’s also something forlorn about it to me.

HF: Right. And the moment we talk about utopia, you also have to talk about dystopia. It’s right next to it as an idea.

I hope that my work carries everything we discussed, but, at the same time, I am aware it also carries something childish. For instance, the billboard might look like a child’s naive idea of “my toys will make others like me.” Or the childish idea of leaving home in search of a new place—certain that it will be easy and fun.

LY: Many viewers, when they first see Almost There, may be reminded of children’s drawings and doodles, but the work is much more accomplished than that. To make this billboard, the actual photogram—with its stuffed animal frame—has been photographed, enlarged, and then printed on vinyl. How do you make these kinds of works? What is a photogram?

HF: I describe these works as light drawings on photosensitive paper, which is a somewhat literal translation of the word photogram. A photogram is a type of camera-less photograph made by shining or blocking light on photosensitive paper. When a source of light hits the photo paper, it leaves a mark. That becomes an image. This is not a new technique. Photograms have been produced since photography was invented. In my case, I have tried to personalize the medium, to put my own spin on it. I have invented various systems to have more control over this process of exposing light to the paper.

To describe the process simply—I make the photograms by using a flashlight and slowly shining the light on the surface of the paper. And because the paper is photosensitive, it captures or reacts to the light. After I’m done drawing the image—in this case, the boat, the animals, and the human—the paper is developed at a laboratory with chemicals, and what was exposed to the light will come out as a dark mark.

The photo darkroom where I work is completely black. Many people imagine a room with a red safe light, but in my darkroom—and in any color darkroom—there cannot be any light. It’s a pitch-black space. I enter this dark space. I put the large sheet of photo paper on the floor, and I sit on the paper, and I start drawing with a flashlight. Afterward, once the work is chemically developed, the image finally appears. Someone might think it’s very quick, because it seems very childish and doodle-like, as you said. But, in fact, the work takes around eight to ten hours to make. It’s a very long time for a photograph; we think of the medium as very quick. Eight to ten hours working in the dark room to produce one image on one paper is a very, very long time.

LY: It’s surprising how physical and bodily the process is, which isn’t evident in the final form because it’s such a flat, seemingly simple image. You’ve described the process of making the photograms as a performance that’s happening in the dark, a private performance.

HF: Yes, it’s absolutely a performance in the dark. I have never recorded it because I thought that would kill its purpose. But by me describing it, you can imagine someone, over eight hours in darkness, slowly tracing an idea, an image, that they can’t see. The chances of it failing are so high.

LY: You titled the work Almost There, which can be thought about in terms of the image and what it represents. But it also brings to mind many of the other titles you’ve used for various exhibitions: Almost Perfect (2023), Young and Clueless (2022–21), and Getting Closer (2022). It seems like you’re imagining a progression. Even for yourself—how you’re almost there or getting closer to something.

HF: It’s true. Maybe some artists don’t think like this, but, in my experience, an artist has an idea of an arc—where it has begun and where it is going for them. Probably you don’t want to get there. It’s also linguistic. What is the difference between almost perfect and perfect? It sounds close, but the distance might actually be very far. As children riding in our parents’ car, we have all probably asked, “Are we there yet?” And they reply, “Almost there.” And that might be two, three hours still.

With Young and Clueless, which I stubbornly used for a couple of shows, many people questioned why I would repeat the title. My explanation was that during the first ten years of my life in America, I was just a ten-year-old kid. During those first ten years of your life, you are young and clueless. You do not really know much; you are learning. It’s funny—the problem with titling is that you might become the title you are giving it, you know? So by calling my shows Young and Clueless, I was allowing myself to be young and clueless.

LY: You are in a legacy of artists who take on the persona of the fool, the trickster, or the jokester, which is a historical tradition beyond contemporary art or visual art. The court jester can be thought of as someone who can critique and challenge those in power through humor. You’re playing with that too, but it’s about more than the criticality of the role. You really exemplify the wonder of it, the pleasure of playing the fool. It’s clear you’re having fun.

HF: I believe this is happening before even getting to that role. Some artists think of what they make as an extension of expression. They express themselves, their identity, their subjecthood. Other artists may see art not as a tool for expression, but more for communication. I see myself as someone who makes art the second way, as a way to communicate. It’s all communication. That’s why the viewer is so important to my work. Because I’m constantly communicating. I’m constantly hearing what the viewer says, and I’m communicating about something they know. That’s the thing about my art. Even someone seeing it for the first time can guess or assume that they know what it’s about. It’s not someone expressing their specific self or experience. It’s about something that the viewer knows too.

Understanding that, you can see how important the role of the fool is. How important the role of someone who can criticize or communicate about the structure, the system, is. But also make it funny—you need to have a sense of humor with it. Nobody wants to hear a professor criticize our society. Nobody wants father figures to tell them about our society.

LY: Connecting that to your imagery, which can appear so childlike at first glance, the child is the fool at first. They’re learning how the world works—what is what, how things work. And when you came to the US to study, you experienced that again, trying to navigate a new culture and country. You had to learn all over again. But there’s this sense of wonder and curiosity for you in not knowing.

HF: You can shine a light on it. You can question how society or something works.

Again, to put a focus on the point of expression or communication, I do not think anyone wants to express themselves as a fool. The only reason to play the fool is when you are trying to communicate about something outside of yourself, outside of your brain, outside of your studio. This is part of the right of an artist to be able to communicate and comment about life.

LY: How does your biography figure in your work, and how do you approach it? It’s clear that you don’t want it to limit the interpretation of your work, but it also seems that your position toward that is changing. So, how do you want viewers to think about the artist’s background?

HF: I think it develops over an artist’s life. I’m also learning and figuring it out. What I can say is that for the last four or five years, I tried to make art that would not communicate about who I am, where I come from. I tried to hide it to some extent. My work depicts the everyman, the everyhouse, the everysociety—which it is. They represent every house. That house could be in Iran, the US, or Italy— all with a mouse, a cat, and a dog.

I realized over time that there is no reason to hide who I am and where I’m from, my background and my biography. I think the billboard actually represents that in such a surprising way, even to myself; because that’s something I would’ve never wanted to make four or five years ago. And I’m so proud of it, and of doing it today.

Before maybe I wasn’t ready to talk about it because it might become too literal. It might become too much on the surface. And I believe I am now capable of giving it this room, giving it this space, and it makes the work stronger. It makes the work better. It makes the work truer to what’s in my heart, what’s in my head, what’s in my brain.

LY: Your work can be both archetypal and abstract but also very personal and specific. It seems like your process is informed and driven by your vision of what an artist does or should do. You have a core conception of the artist. So even if your art seems to be about family or society, it’s also about you. Your recent exhibition made that more explicit because you incorporated self-portraits in all of these works—paintings, drawings, ceramics. This also suggests that you have all these different guises and can play different characters and inhabit various archetypes.

HF: Looking back, even though I’m Iranian, I’m here in the US, so I’m going to make work that’s American. I think if someone looks at my work, they actually assume it’s very American contemporary art. In fact, I am becoming an American soon, hopefully, but even if I am an American, I’m not just an American. I’m an Iranian who became an American.

The work has to represent that. That becomes the strength of the work. That becomes the surprising part of the work. This is my unique situation, which, like every other artist, I have to communicate and decode. The question is what I am going to do with it.