99 Objects: Christopher Lew on Cost of Living (Aleyda) by Josh Kline

Sep 3, 2015

On May 9, Education launched 99 Objects, a new daily public program in conjunction with the inaugural exhibition America Is Hard to See. Named in honor of the Museum’s new address, 99 Gansevoort Street, these in-gallery programs focus on a single work of art from the Whitney’s collection, with presentations by artists, writers, Whitney curators and educators, and an interdisciplinary group of scholars.

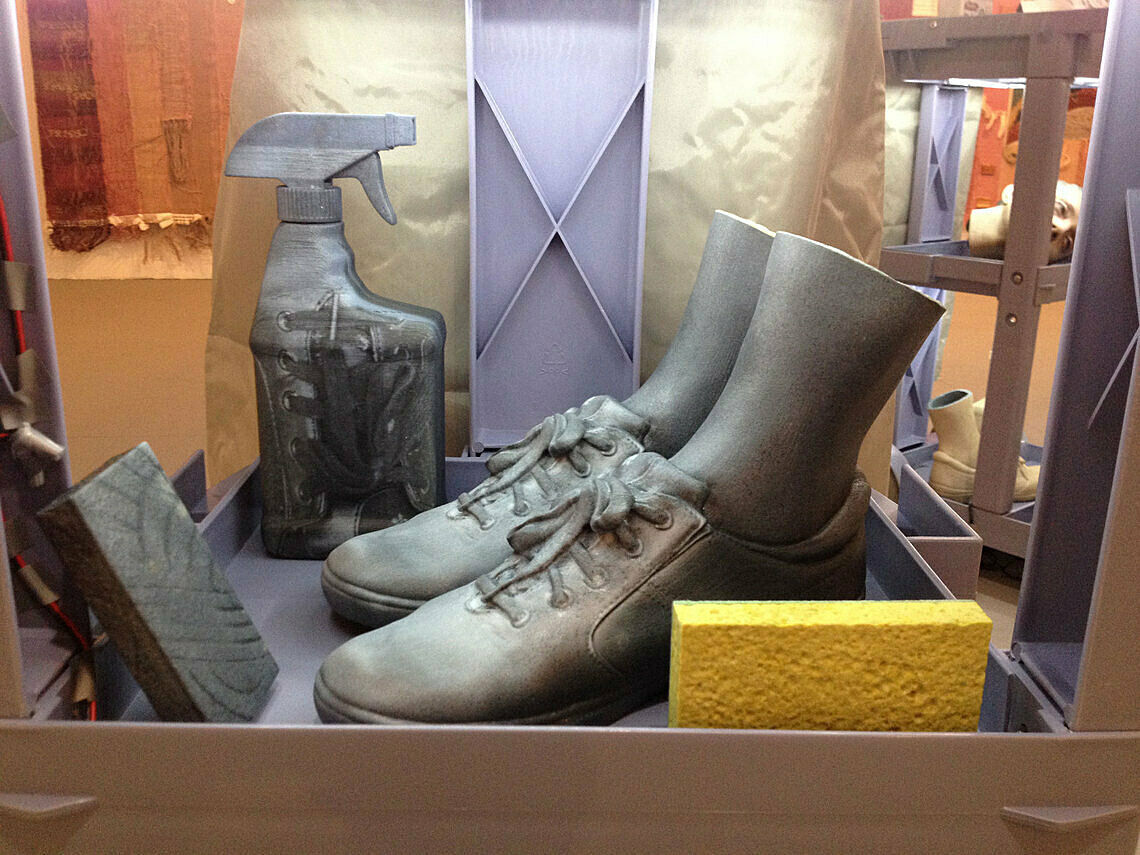

For the third of ninety-nine scheduled programs, Christopher Y. Lew, Associate Curator at the Whitney, spoke about Cost of Living (Aleyda), 2014 by Josh Kline (b. 1979). This sculptural assemblage is part of a series of non-traditional portraits that Kline has made using 3D imaging. To make this and the other works in the series, Kline interviewed workers—janitorial staff and package deliverers—and then made 3D printed sculptures of the parts of their bodies that they use to complete their daily tasks. In this case he spoke with a housekeeper named Aleyda at the Rivington Hotel in Manhattan. The work on view—one of a series of three recent works by Kline that has entered the Museum’s collection—is comprised of a janitor’s cart and objects such as cleaning supplies and sponges that relate to Aleyda’s work.

To create the sculptures of Aleyd head, feet, and cleaning supplies, Kline had photographs taken with two or more cameras. He then worked at a computer lab at New York University to print the body parts and objects with a 3D printer. One of the two heads on the cart is painted realistically while the other head matches the label of her cleaning fmages ofir and barrette are printed on one of the sponges.

Lew discussed Kline’s interest in the impact of technology on workers in the twenty-first century. He explained that Kline’s sculpture represents a non-traditional approach to portraiture that includes not only a resemblance of a person, but also the information that permeates their life—for example, the accessories and objects that relate to Aleyda’s work. Consequently, we can gain a sense of a person from the products they use, but it is a metaphorical impression—we don’t really know who she or he is.

Lew noted that Kline’s work comes with a data set—the digital information required to re-print the objects on the cart if anything is damaged. The artist has requested that any future re-printing would be at the best print resolution available at that time. When asked about the artist’s view of technology, Lew replied that instead of a clear attraction or repulsion, Kline’s work suggests ambivalence toward technology and raises questions about who actually benefits from technological innovation. Moreover, with these portraits, Kline calls attention to laboring bodies and offers a grim reminder that workers’ humanity is often valued less than the tools they use to do their job.

Learn about upcoming 99 Objects programs

By Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources