On View: Tina Barney, The Landscape (1988)

Aug 23, 2013

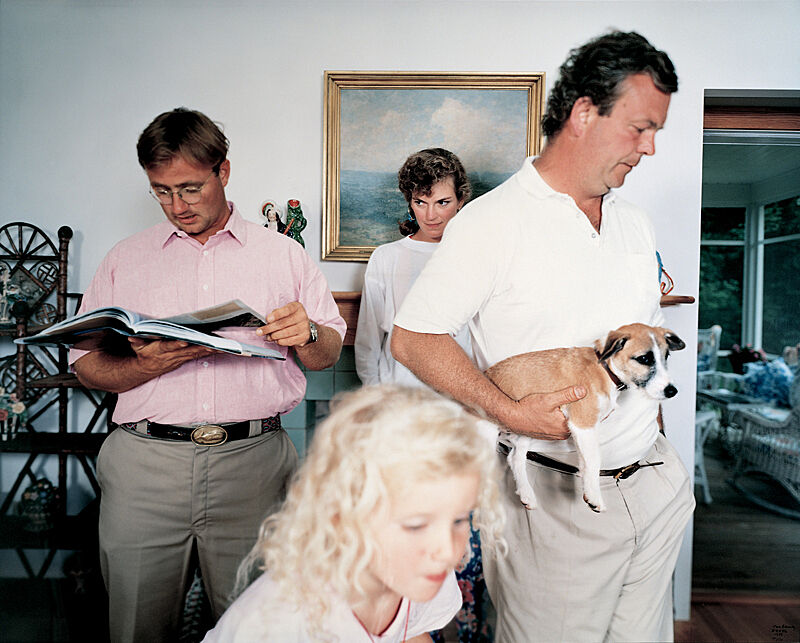

One of the notable aspects of I, YOU, WE, an exhibition of Whitney collection works from the 1980s and early 1990s, is its focus on works from the perspective of socially marginalized individuals and groups. Walking through the galleries, one gets the sense that during this era of American life, new challenges rose to the status quo along with those who have traditionally held power. An exception to this point of view is Tina Barney’s 1988 photograph The Landscape. Captured in the Watch Hill, Rhode Island summer home of her own well-to-do East Coast family, the image is paradigmatic of the artist’s practice in which friends and family are documented in intimate settings.

The title works on two levels: a landscape painting hangs on the wall in the background, anchoring the composition; and there is a metaphorical landscape of intersecting relationships between the four figures and the dog pictured on the right. In the top center, the woman’s watchful, downcast eyes may appear, at first glance, somewhat devious. There’s something about her gaze that lends the whole image the feel of a Hitchcock film still. This may lead the viewer to believe that the artist is critiquing upper class mores, suggesting that beneath the veneer of the respectable family, a lurking malice exists. However, when we follow the woman’s eyes, she seems merely to be looking at the book being paged through by the man on the left of the image. Likewise, it may seem as though the artist is suggesting that each person is absorbed in their own activity and alienated from one another because no one is paying attention to anyone else; but the presence of the little blonde girl in the foreground adds a note of almost angelic familial warmth to the dynamic.

Finally, the expression of the man holding the dog on the right seems perhaps burdened or world-weary; in a way, the look of the dog does, too—its eyes seem forlorn. But, in combination, the two seem to have a familiarity which complicates a simple reading of either figure. What is intriguing to me about Barney’s photograph is how it captures the viewer’s eye and suggests multiple readings, but ultimately refuses to deliver a specific take on the upper-class world in which the subjects exist. She seems to understand that the mind leaps at placing blanket symbols on the people we see in media images. The Landscape cues the viewer to look at it in this way, but then frustrates that attempt. Speaking about this quality in Barney’s work, the critic Michael Kimmelman wrote, “Her work proves how we interpret pictures to match our desires, not the images.”

Gene McHugh, Interpretation Fellow