Painting Now: Abstraction and Figuration

Dec 7, 2012

Whitney courses are multi-week programs that examine key issues in twentieth- and twenty-first-century American art and culture. Painting Now, a five-part course offered this fall, examined the legacy of painting within Modernism and its enduring importance in contemporary art. The course began on October 18 with a lecture entitled Abstraction and the Crisis of the Figure. In her lecture, Joan Tisch Teaching Fellow and program instructor Anna Katz spoke about how figurative and abstract painting, although seemingly at odds, could not truly be separated from one another. Katz discussed the works of numerous artists and themes during her lecture, yet I was struck by one idea Katz conveyed by comparing the abstract work of Jackson Pollock and the portrait painting of Elizabeth Peyton—that artists can simultaneously explore both figuration and abstraction.

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), is primarily known for his large-scale and seemingly non-figurative large-scale abstract paintings, such as Number 27, 1950. To make these paintings, Pollock laid canvas directly on the floor of his studio. He would then move around the canvas, pouring and dripping the paint onto the surface. Katz said that his “pure form” paintings could “still be considered figurative because of bodily action. . .and [because Pollock] poured himself into them.” Although non-representational, the works capture Pollock’s movements, frozen in paint on a flat, two-dimensional surface.

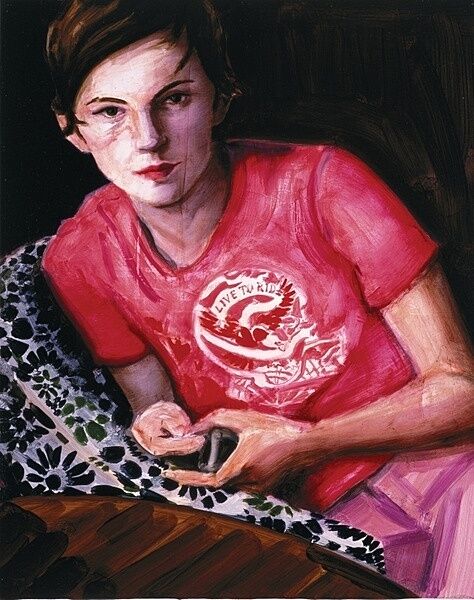

In contrast to Pollock’s large-scale works, the contemporary figurative painter Elizabeth Peyton creates what Katz called “pretty and jewel-like” portraits such as her self-portrait Live to Ride, E.P., which are intimate in scale, often just slightly larger than a sheet of letterhead paper. Peyton’s paintings also portray contemporary rock and movie stars as well as the artist’s close friends. She presents her subjects in a stylized manner with ruby-red lips and translucent skin, rendering them almost androgynous in nature. In combination with the loose, thick, and fast brushstrokes she employs, the images possess an abstract quality. Like Pollock’s work, Katz suggested that Peyton’s paintings could also be viewed as pure form—she is not trying to portray an exact likeness of her subjects and purposefully chooses not to revisit areas of the paint that may contain blotches, drips, and smudges. The artist has said of her painting method that “. . .it’s all mistakes in a way. The overall effect just works sometimes.”

By delving deeper into the works of Pollock and Peyton during the lecture and examining the ways in which both artists paint, Katz helped me understand how an abstract painting can embody elements of figuration, and a figurative painting can also be abstract.

By Aran Winterbottom, Interpretation Intern