Teen Art Workshop with Elaine Reichek

May 4, 2012

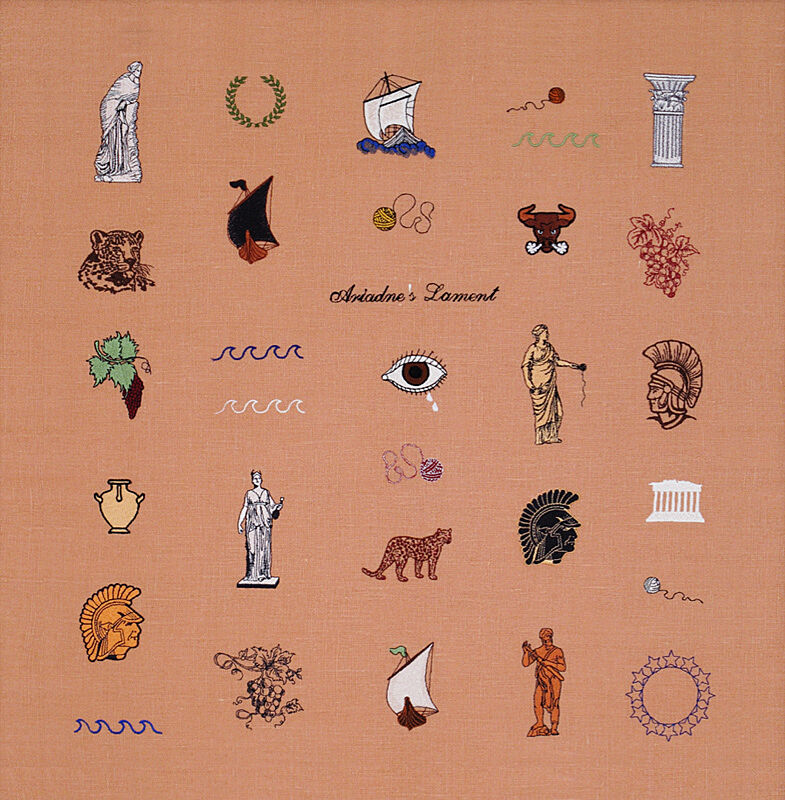

Not many people can effectively explain Titian, T. S. Eliot, and tapestries to an audience of teenagers on a Friday night, but Biennial 2012 artist Elaine Reichek has that gift, plainly evident as she led a workshop for the Whitney’s Youth Insights (YI) participants on March 30. Part discussion, part art class, Reichek focused on her work from her ongoing series Ariadne’s Thread.

This body of work, begun in 2008, chronicles the classical myth of Ariadne. In the tale, Ariadne, a Cretan princess, falls in love with the young Athenian warrior Theseus. Unwilling to see him die at the hands of the Minotaur—a gruesome half man, half bull who lives deep within the labyrinth of Crete—Adriane gives Theseus a ball of thread he can follow to find his way out of the treacherous maze after he slays the beast. The couple runs off together, and although she has helped him outwit the fearsome Minotaur, he abandons her. Initially despondent, she eventually marries the god Dionysus, who makes her immortal as a constellation Corona Borealis in the night sky.

Ariadne’s saga has engaged many of the world’s most prolific artists and writers for centuries. Typically a secondary character in Theseus’s hero-story, Ariadne becomes Reichek’s central protagonist. To explore her story, Reichek reproduces some of Western art history’s most famous images of the myth, not in paint or print but with thread, the same material Ariadne used to help Theseus escape the labyrinth. She uses both hand-sewn and computerized embroidery—the latter is made on digitally programmed sewing machines and looms. Reichek often includes a passage of poetry or prose below the image that more fully articulates the aspect of the story she wishes to emphasize.

Despite her reliance on the medium, Reichek considers herself primarily as a conceptual artist who works with cloth to examine aesthetics and modes of representation. By working with both handmade and computerized embroidery, for example, she suggests a relationship between the way stitches and pixels create images. Reichek’s work has many layers, convening complex ideas about craft, representation, and the relationship between text and image, among others. While her explanations of her work and its meaning are quite scholarly, Reichek made no attempt to over-simplify these complexities simply because of the young age of her audience. Her mini-lecture challenged and engaged the teens, who asked numerous questions about the technique, imagery, and meaning behind each piece.

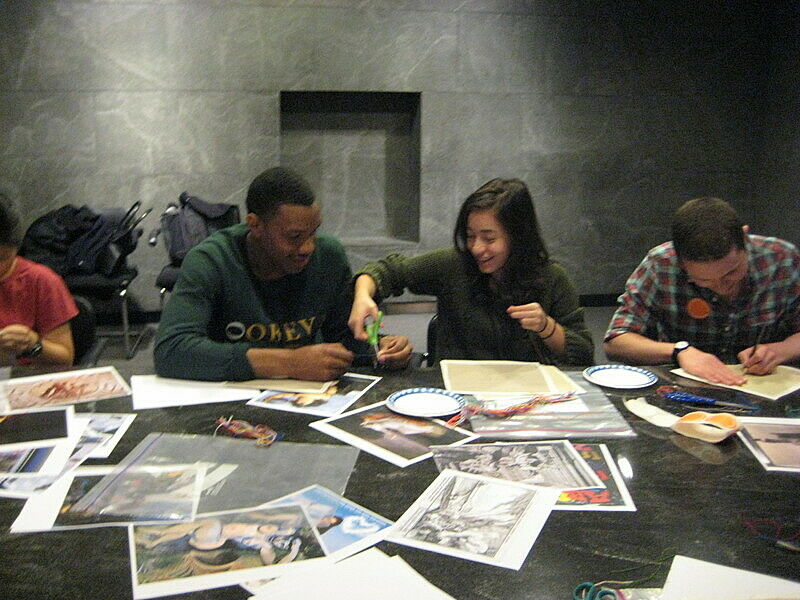

After the discussion, Reicheck led an embroidery workshop. She and Education staff had assembled individual packets for each participant, containing a needle, brightly colored thread, and a square of the same linen that she uses in her own work. Reichek briefly instructed her students on the basics of cross-stitch embroidery, but stressed that freehand stitching can be used to create more abstract designs that are just as beautiful as the most precise traditional styles. Reicheck herself has been experimenting with tapestry since the 1970s, although she was trained as a painter and only learned to embroider more informally. While none of the YI teens had stitched before, Reichek’s personal story and flexible approach allowed everyone to create something wholly unique and conveyed the idea that anyone can master a difficult or unfamiliar medium with practice, patience, and creativity.

By: Elizabeth Pisano, Education Intern